Trade unions have failed migrant workers. To remedy this, we need serious self-criticism

Trade unions and migrant workers in Scotland have a complicated history. While virtually all modern trade unions subscribe to and reproduce the language of equality, diversity and inclusion, a detailed look at the realities of migrant workers in insecure, low paid, and precarious occupations reveals a more troubling picture. History has not yet repeated itself: the dark legacy of trade unions’ open hostility to migrant workers is now a thing of the past, thanks in large part to the enduring struggles of Black and migrant people. However, despite being overwhelmingly concentrated in the worst jobs, migrant workers are woefully under-represented in trade union structures. Attempts by trade unions to organise migrant workers in specific sectors through the provision of language courses or top-down campaigns have proved ungeneralisable. The most common perception is that, due to a variety overlapping factors, migrant workers are ‘unorganisable’.

These perceptions reveal both an unwillingness on the part of trade unions to seriously reflect on their shortcomings, and an equally disturbing tendency to ignore history. Indeed, migrants have been at the forefront of many significant labour victories in the UK. Rudolf Rocker, one of the main theorists of anarchosyndicalism, played a significant role in organising and empowering Jewish workers in London in the early 20 th century. At the peak of this process, meetings by Jewish migrant workers were attended by thousands, eventually contributing to the abolition of the sweatshop system. More recently, the examples of the Indian Workers’ Association and the oft-cited Grunwick strike organised by Asian women attest to the enduring power and potential of migrants to collectively challenge both economic and racial/ethnic oppression. In Scotland, migrant-led formations such as Oficina Precaria and the group Orgullo Migrante highlight that, in 2021, migrants are far from ‘unorganisable’. Yet these examples rarely inform wider narratives about the possibility to organise with, and help empower, migrant workers. A comprehensive history of migrant workers’ labour struggles in the UK has not even been written. As is often the case, silence reveals more than it obscures.

I have been a migrant worker and a union rep in Bradford and Glasgow since 2014. While working in many precarious hospitality, manufacturing, and logistics settings, I was constantly trying to help set up structures that catered to the needs of migrant workers. Our attempts were commendable, yet they always failed or fell apart in the long run. When the opportunity arose to begin a 3-year, fully-funded PhD, I decided to research precisely why these failures occurred. Alongside interviewing migrants about their experiences in work and with unions, I sought employment in those occupations in which the economic system pushes migrant workers in order to document and analyse their (our) realities as directly as possible.

This article is my first attempt to publicly communicate the findings and conclusions that emerged from this process, in the hopes of contributing to discussions already being held in movement circles. While it is impossible to accurately generalise a conclusion over a population as diverse as migrants, I wish to highlight some specific aspects of migrants’ experiences in precarious labour which are, more or less, constant.

Unpacking ‘Unorganisable’: Structural and subjective barriers to migrant worker unionisation

What does the term ‘unorganisable’ really consist of? The theories that come together to produce this perception can be generally split into two strands. The first focuses on the structural characteristics of where migrant workers are located in the nation and the economy. These are characteristics that are external to migrant workers themselves, such as the precarious nature of zero-hours contracts or the debilitating possibility of deportation. The second strand focuses on internal factors that are related to the condition of being a migrant, such as language and cultural barriers. I use the term ‘subjective’ to describe these, since they result in identifiable behaviours that reside in the individual migrant in question.

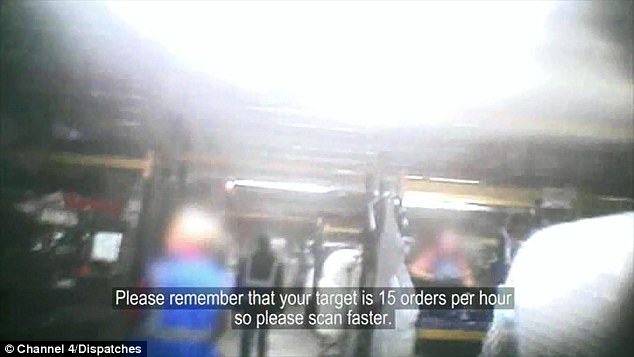

Structural explanations of migrant ‘unorganisability’ are the most common. These are related to oft-cited economic analyses, so I will not delve deep into them. As neoliberal policies have destroyed the former bastions of union might, workers are increasingly isolated and disempowered. Especially at the lower rungs of the labour hierarchy, the rise of zero-hours contracts and other temporary contractual arrangements splinter the opportunities to develop bonds with other workers, in turn eroding the necessary foundations of solidarity. Employers’ extended use of employment agencies- frequently the first point of contact between migrant workers and the local labour market- make this situation even worse. Workers are continuously shuffled between different locations with the constant, debilitating threat of arbitrary dismissal hanging above their heads.

To make matters even bleaker, workers are consistently competing with each other for a limited number of jobs and an even more limited number of permanent jobs.

A permanent contract is like a carrot that is dangled in front of workers’ faces, forcing them to constantly overexert themselves in an endless downward spiral. Precarity is commonly understood as a tool for employers to flexibly meet fluctuations in demand by allowing them to easily hire and fire as they see fit. Yet, it is much more than that: it is a management tool. It enables employers to effortlessly sort through vast numbers of individual workers until they select and retain the ‘best’. These methods create even more hierarchies within the working class and further destroy any potential for solidarity. It is no surprise then that only 14.8% of temporary workers are unionised, as opposed to 24% of permanents. As migrants are systemically pushed to the most precarious and insecure occupations, they are more likely to experience these conditions.

Simply put, those in the most need of organisation are the ones who access it the least.

Subjective factors related to the migrant condition are less common as explanations, but perhaps more insightful. For the sake of brevity, I will skip the obvious issues of language and cultural differences and will instead consider a less noticeable but crucial characteristic called ‘the dual frame of reference’.

Migrants are also emigrants. They carry within them a universe of meanings, ideas, and goals brought from the countries they left behind. This complex of ideas informs their actions in their new country as well as what they consider to be within the horizon of possibility. Frequently, there is a contradiction between these ideas and the realities of the country of migration. The sociologist Michael J. Piore used the term ‘dual frame of reference’ to describe these mental processes that are caught between two worlds.

When it comes to labour, the dual frame of reference mostly manifests itself in migrants’ perceptions of the differences between the wages and conditions in Scotland in relation to those they left behind. Some migrants who view their stay purely instrumentally: for them, the goal is to put your head down, work, and make as much money as possible before returning to their countries. However, the dual frame of reference is strong even in migrants that choose to stay in Scotland. I come from Athens where, after brutal austerity policies imposed by the EU and our local oligarchs, receiving €700 a month is considered a ‘good’ wage (as a point of reference, renting a modest flat can be as high as €400). Most young people are forced to live with their parents until well into their 30s. By comparison, the wages and the personal autonomy offered by a precarious occupation in Scotland do not seem that horrific. By working just two days a week I make as much as my friends back home make in six. This difference can make precarious, alienating, and anxiety-inducing labour conditions tolerable. Risking this newfound comfort for the sake of organising, when one is already in an intensely precarious job, at first may seem counter intuitive.

The ideas about Scotland and the UK that migrants have grown up with from their countries of origin are also crucial components of the ‘dual frame of reference’. An inseparable aspect of Britain’s colonial activity was the dissemination of the idea that it was ‘civilised’, ‘progressive’, ‘fair’. These ideas live on, especially when contrasted to the blatant oligarchies and human rights abuses that ravage less ‘developed’ countries (I am not arguing that these do not exist here- simply that the British and Scottish establishment are better at hiding them).

For example, during my research I came across an Albanian worker in one of the kitchens I was employed in, in one of the biggest restaurant chains of Glasgow. Despite having a very precarious contract, he was convinced that he couldn’t be arbitrarily fired due to his faith in Employment Tribunals. He thought that if they fired him, they would be made to pay him thousands in compensation and would therefore not risk it. In short, he thought that he had considerably more power than he really did.

Lack of information, alongside a (neo)colonially induced faith in the institutions, plays a role in migrants’ reluctance to seek out and join trade unions. Another example of the ‘dual frame of reference’ was recounted to me by a Spaniard: he had been robbed of hundreds of pounds’ worth of wages and was unfairly dismissed, but did not immediately pursue justice since he did not know that in most cases, an Employment Tribunal claim can only be lodged strictly within three months of the date of the incident. In Spain, the space afforded for a similar action is about a year. This same issue was encountered with a Romanian mother of two who suffered a workplace accident that ultimately rendered her unable to use her arm. Taking advantage of her social isolation and her lack of information, her employers (a large multinational hotel chain) simply sacked her. When I spoke to her, three years after the incident, there were very little institutional options that remained available to her. Having to constantly work long and gruelling hours to earn her family’s survival, she never had the time or energy to seek out a union. She told me that unions ‘had to be more visible, people don’t know you exist’.

This combination of structural and subjective factors explains why migrant workers are frequently thought of as ‘unorganisable’. I don’t have the space here for a more coherent analysis, but some fundamental characteristics are clear: the intense precarity that confronts the wider working class ruptures the potential for trade unions to use their traditional methods of workplace organising. The fact that workers move around jobs combines with their insecure contractual situation and makes it difficult for unions to approach them in a workplace setting. The individualisation of the labour experience and the internal hierarchies imposed by management further hinder the emergence of solidarity between workers. On the other side of the spectrum, elements that are related to the condition of being an immigrant combine with these structural barriers and can make immigrant workers more reluctant to join unions. This is due, among other factors, to a combination of a false sense of security, comparing one’s situation here favourably in relation to the one left behind, and the simple lack of information.

Locating the Failure: Union Absence

While the above explanations are helpful, they are nevertheless not enough. Simply put, my research shows that most migrant workers in precarious occupations have never been in contact with a union, with many (especially younger workers) not even knowing what trade unions are or whether they can join as immigrants. This might seem like a simplistic explanation, but it is critical: how are people supposed to trust and join something that has never helped them, or ever even been in contact with them? How are they supposed to access information, if they don’t have access to information?

During my tenure in seven workplaces in Glasgow, I only encountered one union (it was the Bakers, Food, and Allied Workers Union). I currently work as a warehouse worker in Amazon. While the GMB is active in some Amazon locations, we never saw a single union representative approach us in our workplace in Glasgow. The only time leaflets were handed to workers was sometime in 2019 through our efforts with the IWW. In the midst of the recent wave of strikes across Europe, most of my colleagues had no idea what was happening, or why we suddenly received that lofty ‘bonus’ for working during the Christmas period (£300 for permanents, £150 for temps). The few politicised workers in a given workplace are powerless without organisation: our precarity makes it easy to fire us, and we cannot (and should not) be left to organise from scratch in one of the most

important sectors of the international economy.

In all the other workplaces I accessed, the very mention of a union was seen as a joke. The word ‘strike’ was only mentioned in jest, attesting to people’s belief in its impossibility. Union activity has overwhelmingly been pushed beyond the realm of imagination in most precarious workplaces. How can unions reverse this trend except through grueling, painstaking work on the ground? Social media posts and a few public events do not cut it. People need to be approached, talked with, supported. During my research I ended up representing two of the workers I interviewed- both ended up joining and actively participating in the union I was part of, with one being instrumental in establishing her local branch even though we failed to win her case.

My interviews and experiences with migrant workers show that migrants both need and want to organise when presented with the opportunity. Given this realisation, I argue that union inaction is the biggest reason for the lack of organisation of migrant workers. Leila [her name has been changed for confidentiality purposes], a Spanish-Tunisian worker who had navigated many different precarious jobs by the time of our interview, described unions’ absence in the following terms:

Interviewer: And so, why have you not joined a union even though you are in these precarious positions?

Leila: Because I have never heard about them. Like, because I have never heard about them in the UK, because I have participated in some of them in Spain, but here, because I have never heard about them, therefore I automatically realise that they not gonna be of any help to me, because they weren’t in any of the places that I been. I’ve never seen them, I’ve never seen any… I’ve never received any leaflet, any nothing from them saying ‘look, this is us, if you need anything this is where you can find us’, so yeah. Like, I haven’t taken them any consideration because they haven’t, like, they haven’t succeed in the effort to reach people, so is just not an option for me.

[…]

Interviewer: OK, and how does that make you feel about unions in general?

Leila: Well, as I said, like, you know, I have completely assumed that if I had a problem, I would never rely on them, I would try to find another way. For me, they don’t exist at all.”

Community Embeddedness: An Unavoidable Task

It should by now be clear the unions and social movements aiming to organise with migrant workers must find ways to make their presence felt. All the problems stemming from the ‘migrant condition’, such as holding wrong information about their labour rights, are remediable only through contact with workers. All the problems stemming from the structure of the economy, such as individualisation and worker transience, can also only be addressed through presence. No matter how proficient unions become in using the catch-phrases of equality and inclusion, they will ultimately have to contend with the fact that the vast majority of exploited, precarious workers do not trust them, if they even know they still exist.

In the face of this overwhelming combination of barriers, most unions have been confined to campaigning against zero-hours contracts, maintaining that only once precarity is overcome will it be possible to consistently organise the ‘unorganisable’. This is basically akin to a dog chasing his tail since precarity has proven triumphantly successful precisely at curtailing unionisation and therefore reducing union power. Unions have also tried to combat the debilitating effects of migration controls in their public proclamations (although recently Unite betrayed us) and have tried to include migrant workers by offering training courses and English language lessons. However, these efforts are also circular since they engage with the limited pool of migrant workers that unions already have access to. As has been argued above, the problem is precisely that this access is extremely limited.

All these factors considered, it appears that the only long-term sustainable option to organise with, and empower, migrant workers is to be found in community organising. Instead of organising people strictly through where they work, unions need to re-establish themselves as central actors in the environments where people live. While it is impossible to develop trust and solidarity in a warehouse which you will depart from in a month, it is possible to do just that in the neighbourhood where you dwell.

The Angry Workers group in London have been engaging in this activity for years, albeit with very limited resources. Recently they have been involved in a new initiative called ‘Let’s Get Rooted’, aiming to develop local, worker-led, grass-roots groups around the UK. I urge every reader to check it out and contact them. What would our society, and people’s wider class consciousness, look like if unions and social movements were actually present in the communities they claim they empower?

The examples of Workers’ Centres in North America as well as various squats and community centres around Europe offer some answers. These radical institutions, often led by migrant workers themselves, have been significantly more successful in organising the ‘unorganised’ than efforts in the UK and Scotland. Against the transience of precarity, they are permanent points of contact in the neighbourhood. They still offer language classes, training sessions, and individual representation. Yet they are open, visible, and accessible, allowing workers to come to them while at the same time continuously doing outreach campaigns to further their presence. They have absolutely no relation to the hierarchical, professionalised, service-oriented ‘charities’ that have infested most of our neighbourhoods. They are not ‘neutral’ entities: they are class-conscious and

ready to fight. Instead of ‘helping’ what they understand to be passive recipients of their gracious aid, their main goal is to develop tools and knowledge that will enable the oppressed to fight for themselves. When migrant workers become more powerful, the entire class becomes more powerful. Crucially, the development of bonds of solidarity between the local and the immigrant working populations can only occur after the marginalised have established access to some sort of collective power.

Such a range of developments would require a significant reorientation of resources and energy towards developing local structures that are firmly embedded in neighbourhoods and daily life. They will need much more detailed work than holding marches, events, and engaging in campaigns that cater to those already organised. They will involve arduous meetings, hours spent standing outside precarious workplaces in industrial zones doing outreach work, and a deep and sometimes uncomfortable engagement with people’s lives and opinions. And they will require time: even if everything I am arguing for was magically established tomorrow, in a year we probably still wouldn’t see much breath-taking change. Yet it is the unavoidable first step. Instead of focusing on the barriers that impede us, it’s time to seriously explore what we can do to overcome them.

So, why can’t migrant workers unionise themselves? By doing so, they might help to revitalise not just the economy in Scotland, but also unionism and its ethic of independence and self-help.

Hello, this is the author. Thanks for taking the time to read this. Migrants have, and still do, organise themselves. However, I believe that in the article I outline numerous reasons why this is always very difficult. See the ‘structural and subjective barriers’ section and the part where I talk about Amazon. However, the problems I talk about do not only concern migrants- they are issues of wider union strategy and are also related to how they approach ‘non-migrants’. To seriously have any hope of reaching both migrant and non-migrant groups working in these industries, unions have to go back into the community, regardless of what individual migrant groups do. Have a nice day!

Yes, I suppose what I’m saying is that the contribution to Scottish society of migrant workers acting directly in organising themselves into independent self-help syndicates, which might (or might not) then affiliate with one another and with established ‘corporate’ trades unions, would be greater than that of waiting for the established corporations to organise them.

I believe the IWW has been instrumental in supporting this sort of mutualism among migrant workers in various parts of Britain.

I know it can be tough, but communities organising themselves is always tough and always face tough opposition from all those who seek to keep them disempowered. There’s little for it but to keep on plugging away.

Thanks for your comment. I am in absolute agreement with you. I was myself a member of the IWW for around 6 or 7 years, and most of my organising work was done with them. I was involved in setting up the Clydeside IWW Migrant Workers’ Network, which intended to do precisely what you describe. You can check out this article where I outline my personal ideological position more clearly: https://interregnum.live/2018/01/22/the-crack-in-the-edifice-modern-capitalism-migrant-workers-and-social-movements/

This specific article was only intended to discuss my findings with wider society, which necessarily involves communicating in a way that is relatable to a much broader spectrum than our (unfortunately) small ideological anarchist/communist/autonomist/syndicalist/etc groups. In addition, there is the simple issue of cash and resources. We don’t have a lot of resources, but we do a lot of work on the ground. Some more resources would go a long way. In contrast, you have huge unions with millions of pounds who constantly drag on about how the love migrant workers, yet do so comparatively little useful work on the ground despite their resources. I wanted to highlight how, based on my research, such unions need to completely change most of their outlook if they want to actually accomplish what they preach. Plus, setting up community spaces would help the rest of the movement also, including its more radical parts!

I hope that I have made my position and goals of writing this article a bit clearer. On the whole, I wholeheartedly agree with you.

Best of luck, Panos!

This was so great! Thanks so much, Panos!

What an excellent article. You do very important work, Panos.

I had never really considered some of the barriers that exist for migrant workers with regards to joining unions. But what you have described actually makes a lot of sense.

I’d love to read more about this sort of thing. If you have written anything else that is publicly available, please do share.

Thank you for your comment. Unfortunately I have stopped being active in union processes since I didn’t have the time to balance them with the final stages of the PhD. Just had to clarify that because I don’t want to take undue credit for something. If however you are referring to the article, thanks a lot!

As for more writing, you can find some stuff here: https://interregnum.live/author/panosapatris/

In the next few months, I will release a much more detailed article on precarious labour on ROARmag: https://roarmag.org

Have a nice night!

Trade Unions have failed most workers , migrant or indigenous . Lions led by donkeys ( in sharp suits ) for the most part . Leaders too busy fighting for their little empire to see the big picture .

Thanks for your comment. You are right. I started my research focusing on migrant workers because I am a migrant worker and we experience some extra barriers, but immediately it became clear that there also a lot of shared experiences with British workers, especially when it comes to unions’ absence from our lives. I believe that a focus to deep community action and presence is the only way for unions and other social movements to seriously work with every community.

Useful to have a critical and evidence-based perspective.

The employers’ duty to consult workers of changes in theory gives the workers time to organize a response before changes are forced through, and this is more likely to happen through trade union representatives, I guess:

https://www.gov.uk/informing-consulting-employees-law

Mergers/expansions/contractions, changes in terms and conditions, various planning/policy/emergency/opportunity changes, new orders/services/product lines, that sort of thing. Perhaps health and safety issues are the big one at the moment?

Another potential benefit of union involvement is training and practice in democratic skills, which the article ends on. Though some people will likely become disenchanted or even burnt out.

Thanks for your comment.

As you say, the law does give some room for action. Yet if there are no unions in a given workplace, even these small opportunities cannot be used.

As for the burn out, I agree that it will happen. This calls for an entire new article, but unions/movements would have to make sure that democratic participation and the sharing of labour is as equal as possible, ensuring that burn out is limited. If a group/organisation ends up being 10 people doing all the work and 200 people just being members on paper, then I believe it might as well just self-destruct and look for what went wrong. Even if these 10 people are superhumans, they will probably fail in establishing sustainable actions or structures.

This leads us to a discussion of internal democracy/ rights and responsibilities/ hierarchies etc. There are many layers, but thanks for opening the discussion about them.

Unions are failing black, migrant, female & disabled workers because they are institutionally racist, sexist & corrupt just like our workplaces where discrimination, racism & sexism is rife