How to Report on Violence Against Women

Iris Pase interviews Laura Tomson, one of the Co-Directors at ZeroTolerance.

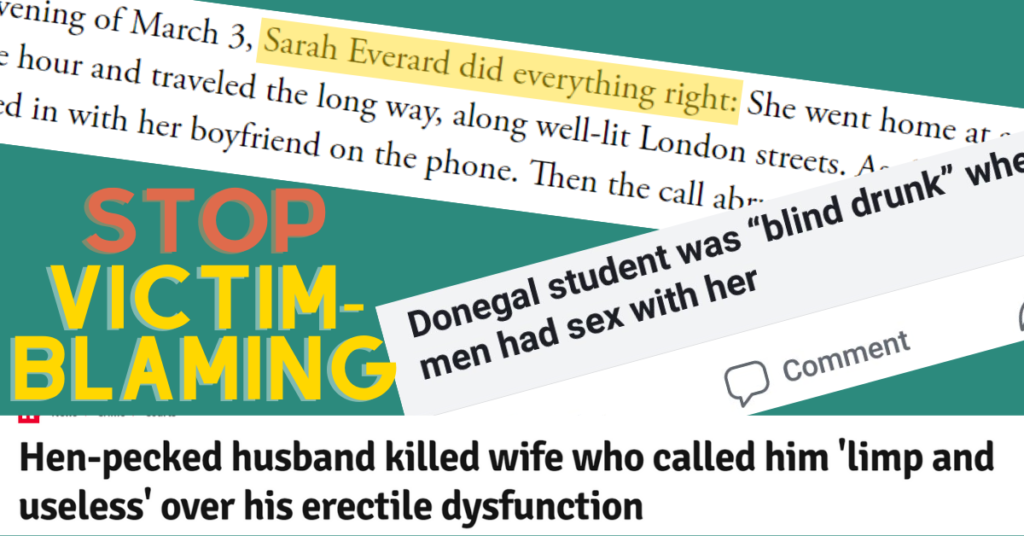

From the public debate sparked by the tragic death of Sarah Everard to cases of everyday gender-based violence, the past month has seen an increased news coverage on violence against women. As often happens, however, when one jumps on a new “trending topic” without adequate knowledge or without consulting experts, the wealth of news, hot takes, and analysis on the issue has shown that we, as journalists, have still a long way to go.

In order to learn more about how to respectfully report on gender-based violence, Bella Caledonia has interviewed Laura Tomson, one of the Co-Directors at ZeroTolerance. ZeroTolerance is a charity that works to prevent violence against women, “which means to stop it from happening in the first place by changing the attitudes and behaviours that perpetuate it,” Laura says.

During our chat, she talked about how to reshape mainstream narratives and challenge traditional reporting practices to better cover gender-based violence. You can find an extensive outline of the following dos and don’ts in ZeroTolerance’s media guidelines.

Avoid sensationalism, opt for contextualisation

When reporting on gender-based violence, journalists should keep in mind that victim-survivors are first of all people, despite their story’s appeal. Therefore, coverage should be empathetic and should avoid disclosing graphic details about the crime or personal details that are not relevant to the story.

It’s also important not to reduce the occurrence of gender-based violence to individual cases. These are part of a larger problem that needs to be acknowledged and highlighted by offering statistics and quotes by experts and survivors.

Don’t use triggering pictures

When writing on domestic violence, for example, reporters need to avoid using pictures of bruised women. “I know it gets a response. People maybe use them thinking that it is stimulating empathy with victims of assault but, actually, what it does is it perpetuates this idea that abuse is always physical. And we know that’s not the case.”

These kinds of pictures also perpetuate the idea of women as weak and passive, which makes it more difficult for victims of domestic violence to see themselves in the story and seek help.

Laura also highlights the importance of representation: ”It’s really important to use images of a variety of different women, because there isn’t just one type of woman that is potentially the victim of violence.” ZeroTolerance actually offers a bank of free to use, ethical, diverse and impactful stock images, created in partnership with Scottish Women’s Aid, which you can access here.

Victims-survivors are never to blame

“I think the one thing that needs to change the most is probably the victim blaming,” says Laura. While she doesn’t believe that journalists are deliberately blaming victims, she argues that “they’re trying to find something to write about and they are, like all of us, part of society. This means they have the same myths and negative attitudes that a lot of women have around violence against women.”

As a consequence, reporters need to avoid publishing details such as what the victim-survivor was wearing, how much they had to drink, and whether or not they had a previous relationship with the perpetrator. This kind of information takes the blame away from the perpetrator and shifts the (negative) attention on the victim-survivor.

Laura tells Bella Caledonia how even the construction of our sentences can change the way we are shaping the story. “Saying ‘woman was raped’ is very different from writing ‘man raped woman’.” She continued: “The way that we talk about violence against women depicts the problem as this phenomenon that comes out of nowhere, that isn’t about particular people’s choices. It’s just something that happens to women and the focus is on women and never on the choices of the men that do these things.”

The language you choose shapes public narrative

Using phrases like “sex scandal”, “sex”, “crime of passion” or “lovers’ quarrel” makes sexual violence sound consensual or it downright minimises and sensationalises violence against women. It’s important to name the crime instead of romanticising it.

When describing the woman or women involved, the term “victim” should be used in three instances only:

- when the woman describes herself as one;

- in case of femicide;

- when discussing the crime or the criminal justice system.

“Survivor” is the preferred word for any other situation. However, if you are interviewing someone, the best option is to ask her directly how she would like to be referred as.

Demonising or over-empathising with the perpetrator helps nobody

When describing an alleged or confirmed rapist as a “good guy” or specifying that he comes from a “good family”, we are minimising the seriousness of his crime. Talking about Sarah Everard’s case, Laura commented: “What can you ever gain from asking these questions, particularly of people who are neighbours or distant relatives? You’re ever only ever going to hear either ‘I thought he seemed nice’ or ‘I thought he seemed weird’ and neither of those things tell us anything. We know that perpetrators of violence against seem like ordinary men.”

The risk of over-empathising with the perpetrator is implying there is a reason for their out-of-character behaviour while also erasing the victim’s experience.

It is also important to avoid going the other way and calling perpetrators “monsters” or “beasts”. “The reason that we don’t like seeing headlines that call perpetrators beasts or monsters is because that makes them seem like aberrations, like most men would never do anything like this.” Similarly to excessive empathy, the demonisation of violent men promotes the idea that the occurence of violence against women is a “one-off”, whereas statistics show that the issue is not only frequent, but cultural.

Always include helplines

When reporting about violence against women, include helplines and useful resources for your readers.

“I would like journalists to be aware of the different women’s organisations that can support women so that, if they were putting on a case of rape or sexual assaults, they’re putting in the number of Rape Crisis Scotland. If they were writing on domestic abuse, they’d have the Scottish Women’s aid helpline and so on,” Laura says.

How to get help: Scottish Women’s Aid can be reached 24/7 at the number 0800 027 1234, while you can contact Rape Crisis Scotland at 08088 01 03 02 any day from 6pm to midnight.

I understand there are often double standards applied in reporting on violence against women, who may be scrutinised for things that the article writer would not look at in a man. However, there are surely cases where violence (or provocation) happens on both (multiple) sides, and to be fair, this should be recognized. In the case of Sally Challen, it was widely recognized that her husband, although victim of her deadly assault, was culpable of years of abuse.

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/dec/10/sally-challen-release-prison-husband-murder-appeal

Two female social workers familiar with child-and-family cases have told me that they encountered female cruelty (to men) on at least a par with males (and this surprised me). I understand about gaslighting and psychological projection and transferrance of guilt, and survivors may unjustly blame themselves to some degree. And believers in a Just World are also likely to blame victims. But I am struggling to reconcile these views. Is it not better to say something along that lines that while the vast majority of women and girls are innocent victims of violence, it is not always that black and white, accepting all the other points made here?

“Two female social workers familiar with child-and-family cases have told me that they encountered female cruelty (to men) on at least a par with males (and this surprised me).” – And I too find this surprising – perhaps the social workers’ definition is different when comparing what applies as female cruelty to men, as opposed to male cruelty to women. Would be interesting to see their definitions. I’ve no doubt that women can be both physically and mentally cruel and manipulative to men, but despite this, I am reminded of Margaret Atwood’s quote: ‘Men are afraid that women will laugh at them; women are afraid that men will kill them.’ The statistics, sadly, affirm this quote.

@greenergood, yes, I don’t expect anyone to attach any weight to my anecdote, but perhaps it would be useful to have some qualitative evidence, views from the trenches as it were, alongside the quantitative statistics. Women have as much agency as men (something many female writers have stressed, such as Agatha Christie), and we see a capacity for cruelty in cases such as the Magdalene nuns. I understand the danger of, even in a very few cases, talking up the culpability of a female victim of gendered violence, but there is a corresponding danger of teaching total exculpation for any group. There is no original sin, and there are no saints. If, for example, a female police officer shot a member of the public and claimed it was an accident, the fact that the officer was a woman should not (in my view, applying a single standard) make us more likely to believe her (for stereotyped gender reasons) than a male officer.

We are still trying to unpick nature from nurture in many areas, as Angela Saini summarises the science in Inferior: The True Power of Women and the Science that Shows It, partly because of past bad science done with male bias. Saini writes about mammal research, for example, that there is no reliable correlation between size and dominance; and earlier research overstated the effects of hormones on sex-differentiated behaviour. A lot of behaviour seems to be societally conditioned, and the vulnerability of women is often down to their comparative isolation in environments like our society. Aggressive, macho cultures can flourish online, although again we need more data on how many anonymous online attacks on females are by other females. Yet we have still to see the longer-term effect of newer role models like today’s higher-profile women football players (and BBC Sportscene is now covering the Scottish Women’s Premier League).

However, I entirely accept your point about the statistics on violence causing actual bodily harm and death. There is an element of patriarchal terrorism here, that has been present throughout my lifetime, although it may be possible to dismantle it in the next generation or so, and language has undoubtedly a major part to play.

Useful article with actionable content, thanks.

Hi. I see that there was another protest for violence against women yesterday, in Plymouth, where I live.

I have a story that I would like to make public regarding the police, Plymouth city council, DEVON county council, Cambian Group,with regards a severe vicious, lengthy and unprovoked attack on me by a male child – 22 months ago.

None of the above did anything about it and it includes lack of duty of care, lack of support and not adhering to basic safeguarding

Please get in touch. It is a very shocking and disturbing case which I have tried to fight for the last 22 months alone.

There has been a lot of blame shifting and victim blaming.

The lad in question was 6 ft tall and I am 5 ft 1 and the story is very harrowing and has been left with no justice.

I have suffered greatly and been diagnosed with high end PTSD and Comorbid symptoms as a direct result of what happened to me. My life has been destroyed.

Regards

Sarah RICKARD