A Memorial for Scotland’s Witch Trials

Circle of Friedrich Brentel the Elder – A Witches Sabbath at the Full Moon, 1580-1651

The witch has become a paradoxical symbol of female power, and of female oppression. She is not simply a creation of the patriarchy; women (indeed anyone who identifies with the witch) have invested in the character as a fantasy which allows them to express untidy desires and revolutionary ideas.

I became actively invested in the study of witchcraft, and the subjects which revolve around it, in 2018. I have a penchant for the eldritch, being raised on a healthy diet of folklore and grim fairytale, and in a house where one could often find a copy of the Fortean Times lying around. This formative insight into the uncanny has left me with a deep fascination for the cryptic and arcane niches of human existence.

2018 saw the immediate aftermath of the #MeToo movement. We were experiencing a societal paranoia: a fear of women’s words. There was non-magical sorcery afoot – words uttered which had the power to affect negatively their subject (however deserving). We were living through a rebalancing of power, and it was a force that was striking terror into the hearts of some men. I considered the backlash to be a contemporary example of the public hysteria that surrounded the witch trials. I was interested in this, and in other historical intersections of gender, language and power.

As I researched witchcraft and the witch trials, the field began to open up for me, in that way that a subject will when you look a little deeper. I became sensitive to the subject of magic – its implications and knotted connections – in the world around me. Just as a word will appear everywhere once you have added it to your vocabulary, I began to notice what seemed to be a creeping miasma of witchcraft: it was there in film, on television, in exhibitions, and as a subject, it was spreading through the literary world. Had it always been there, under my nose? Or, had a lot of people turned to the study of witchcraft at the same time as I had?

“There’s been an incredible upsurge in stories, non-fiction and general publication on witchcraft and magic,” says Alice Tarbuck, when I ask if she agrees with my conjecture, that there is a recent increase in interest on the subjects of magic, witchcraft and the witch trials. Alice is a poet, academic and author of the brilliant ‘A Spell In the Wild: A Year (and Six Centuries) of Magic‘, published in 2020 by Hachette – a kind and bosky book, a salve to read which I highly recommend. Primer-cum-chronicle, ‘A Spell In the Wild’ recites nature’s calendar, explores accessible magical practice and reflects on what it means to be a self-identifying witch today.

The witch is no longer necessarily an eerie figure, haunting history and literature’s darkest corners; nor need she romp with the devil or indulge in osculum infame to earn her title. Now she makes marmalade. She tends to the natural world around her; takes what it has to offer and, in turn, offers herself up to it. She communes with the wild, savours its remedies, acknowledges its animism. In short, she notices. She cares. As the publisher’s copy of ‘A Spell In the Wild’ states in bold letters : “Magic is back”. But why now?

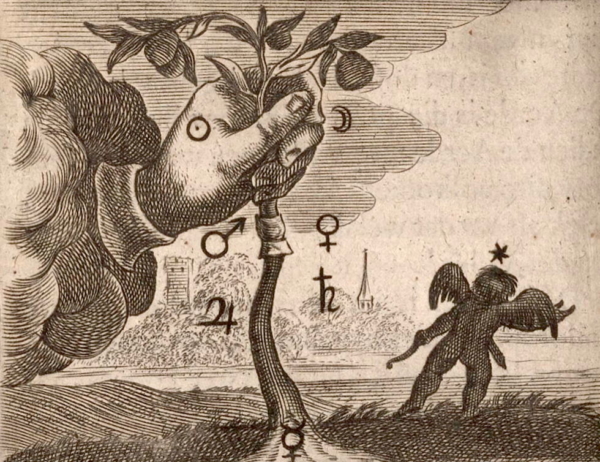

Alchemical drawing

“Populations always turn to the occult and means of finding personal power outside the establishments we live in whenever there is a swing to the right in politics, and whenever there is a recession and austerity,” says Tarbuck. “Whenever personal agency is useless in the face of the state, witchcraft offers an opportunity for enchantment outside the spell of capitalism.”

This is certainly an interesting interpretation, and one that I find myself agreeing with. Language falls short when it comes to describing concepts such as ‘magic’ and ‘witchcraft’ with any kind of precision, because of their abstract, metaphysical nature, but if I had to formulate definitions I might opt for something like ‘personal agency’, the employment of lore, or wisdom. (I am reminded of the ‘headology’ applied by Terry Pratchett’s witches).

Within the slick (and similarly abstract) international systems of capitalism and commerce we are relatively powerless as individuals, so then witchcraft allows us to become part of something bigger, to affect change in our immediate environments: in our communities, our habitats, in ourselves. And, if today’s witchcraft is concerned with personal agency outside of capitalism, then, perhaps, the supposed diabolical witchcraft of the past was doing something similar, but from within the power structures of that time: church, monarchy and patriarchy.

Capitalism’s intoxicating spell infiltrates all. Walk into any high street shop right now and you will no doubt see an array of plastic products adorned with suggestively mystical symbols, fast fashions bearing the somewhat queasy and worn-out slogan, ‘We are the granddaughters of the witches you couldn’t burn’. Witchcraft, or at least, its aesthetic, is not immune to becoming commodified, and we are in danger of romanticising the torture and torment of innocent people.

Alice Tarbuck points out: “It should be made clear that witchcraft falls into two distinct categories: the witch trials are an example of genocide in order to increase social control and compliance, and there is no material evidence that anyone executed in these trials ever had occult capabilities or leanings. They were victims of persecution, executed on confessions extracted under torture and circumstantial evidence. Practitioners and those interested in the occult in a contemporary setting do not ‘descend’ from these people, but nevertheless, have a duty to remember and celebrate them.”

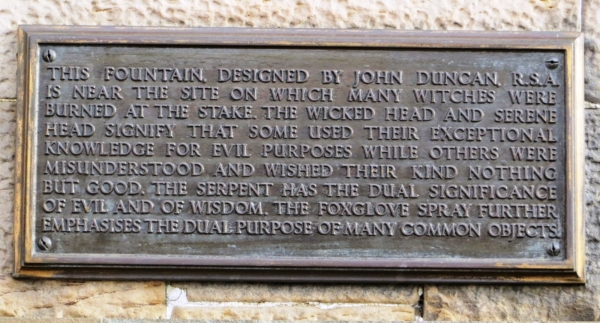

The Witches’ Well, a cast iron fountain and plaque, honors the Scottish people who were burned at the stake between the 15th and 18th centuries. Patrick Geddes commissioned John Duncan to create it in 1894.

Two such people who are doing their best to remember the victims of the Scottish witch trials in particular are Claire Mitchell QC and Zoe Venditozzi, hosts of the podcast Witches of Scotland, and the driving force behind a campaign to get the Scottish parliament to pardon and posthumously apologise to those convicted of witchcraft.

There was a proliferation of witch trials in the period between the mid-sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries in Europe and the New World. This was not, however, one sustained crusade. These were scapegoating outbursts of social upset and hysteria, caused by political and economic uncertainties, guided by paranoia and discrimination (all sounds frightfully familiar). Although many men were convicted of witchcraft, the vast majority of those tried and tortured were women. This was especially true of Scotland, where women made up 85% of those convicted.

When I ask Mitchell and Venditozzi why they think Scotland so enthusiastically prosecuted alleged witches, they tell me that “This question has been considered in detail by academics, but in short, it is a combination of a number of factors: the availability of local courts to air grievances, the control of the church over the people and the fact that King James VI was obsessed with witchcraft. His obsession provided a legitimacy from the very highest parts of society.” (Time really is a flat circle).

As with defining witchcraft, it is difficult to pin down one reason for Scotland’s particular fondness for prosecuting vulnerable women as witches. Other contributing factors could include John Knox and his ‘monstrous regiment of women’; the Reformation flexing its muscles to compete with Catholicism; the prevalence of the uncanny in the everyday, with native folklore and faerie-tales threatening God’s primacy. It is easier, however, to understand why so many of those accused were women. As Mitchell and Venditozzi point out, “The reason that 85% of witchcraft accusations were women was based on the premise that women were less able to deal with the Devil, more likely to be swayed by him and succumb to his charms, so at the heart of the allegations was the idea that women were inferior to men.”

The third goal of their campaign is to erect a national memorial to the victims of Scotland’s witch trials. They say, “I think it is important that we properly remember history and where things have gone wrong – very wrong in the case of witchcraft – and address it.”

I agree. A memorial would be an opaque reminder of one of the darker parts of Scotland’s history, a cenotaph and mark of respect to victims of genocidal misogyny. Our landscape is haunted by historical sites of female persecution, and yet women remain so obviously absent from our nation’s plinths. The #BlackLivesMatter movement has sparked much important public discussion on the political implications of how we memorialise, who is lionised in history books and immortalised in street names and who is actively forgotten. I will point you here in the direction of Sara Sheridan‘s brilliant article for Bella Caledonia on her book ‘Where Are the Women?’, which you can read here, in which she says that “male history is simply known in more detail” than women’s. Yes, generally in history, everyone, other than white men, are outsiders.

Norway’s Steilneset memorial, commemorating the trial and execution in 1621 of 91 people for witchcraft.

Jenni Fagan‘s latest novel is Luckenbooth. It describes the interlocking histories of nine outsiders, over nine decades, all residents of the storied, and nine storey, 10 Luckenbooth Close: a cursed Edinburgh tenement, built atop catacombs. As sexy and horrifying as any fairy story, it is a book concerned, not only with a structure, but with structures: alphabetical, architectural, societal, what they are built upon and how they crumble. Fagan is a writer who writes witchcraft, with a poetry collection entitled ‘There’s A Witch In the Word Machine’ and an upcoming book about the North Berwick witch trials. There is a witch in ‘Luckenbooth’, but all the characters are, like witches, outwith what is considered to be conventional. Poor, homeless, queer and eccentric they inhabit, without properly participating in, the Capital and capital.

Normal rules do not apply to magical beings, and that is what makes them so useful to storytellers. Likewise, outsiders can defy, and deny, generally accepted realities. Fagan reflects the zeitgeist by suggesting that uncomfortable truths about the past threaten contemporary structures. It is not until a buried crime is unearthed, acknowledged and set free that 10 Luckenbooth Close’s curse can be lifted. And might not this be the reason for the apparent ubiquity of witch literature at present? It is through stories that we make sense of our past and of ourselves, and the witch is an archetype that questions the conventions of the world which we inhabit. And the world which we inhabit has needed some pretty forensic questioning of late. As Christina Larner says of the witch in her brilliant academic text, ‘Enemies of God: The Witch-Hunt In Scotland’:”She has the power of words”.

When I asked Alice Tarbuck what important lessons she thinks that magic has to teach us in the modern day, she responded: “That we are beings entirely connected to the natural world. That we are not autonomous nodes, but inextricably part of the planet – our bodies contain both magic and microplastics, germs, bacteria and the same brightness that moves wind through birch trees. It also teaches us that there are ways of understanding the world that allow us to move through it with compassion and cooperation.”

It has been said that religion is the greatest obstacle to the sacred; in a similar fashion, it could be said that magic (in its various spellings) is an obstacle to power. Real power is not metaphorical, incantational, nor is it mere sentiment. My observation of covens and gatherings of the self-identified witch crowd is it’s mostly play (playful, full of play) and that in itself is agreeable enough…especially as it is a break from the greater part of what one does the rest of the time to survive (work) and to tolerate surviving (consumption). It’s good to play–but that shouldn’t be mistaken for power, action that does transform our world. Again from observation and experience, it’s my conclusion that most people who focus on rituals and approximations of power are playing at it–playing at power. Okay, maybe that’s healing in the way that any therapy is (there’s even such a thing as “play therapy”). But that’s not sufficient to the task; “thinking good thoughts,” “being the change,” and self-improvement each contain a fragment of validity…but all are insufficient to the task of the world we inhabit–as I keep hoping humanity will urgently take to heart, before we are crushed by nature–which doesn’t give a fig for ritual, metaphor, or any other magical undertaking.

Aye, but the criminalisation of witchcraft in Scotland between 1563 and 1735 wasn’t about magic; it was about power. It was about the power of the kirk sessions (the ‘soviets’ of 17th century Scotland), and the ecclesiastical courts (presbyteries) that oversaw them, to control the behaviour of men and women. The 3,000+ people who were accused of witchcraft during the period (84% of whom were women), and the 1,500+ who were subsequently executed, were persecuted out of local malice and for little other than deviance. It’s good that this dark period in the history of the Scottish people is commemorated for the edification of the present.

Agreed. Glad to see the article, no objection to it whatsoever.

There is no word in Irish or Scottish (Gaelic) for ‘witch’. Bean feasa (wise woman) or cailleach (old woman) have positive connotations.

Witch hunting comes with language shift to English personified in James VI.

And yet the 1563 act of the Scottish parliament that made witchcraft a capital offence precedes James VI. That was the same parliament that in 1560 sanctioned the Reformation. Moreover, the 1604 act of the English parliament simply brought England into line with Scotland with regard to the criminalisation of witchcraft; although it led to far fewer prosecutions in James’ southern kingdom.

I don’t think you can lay the fault for the persecution of witches in early modern Scotland at the door of the b*st*rd*n English. Nice try, though!

In Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, author Silvia Federici describes how new opportunities opened up for women after the peak of peasant revolts passed, especially in cities (apparently there were 16 female docters in 14th-century Frankfurt) but there was an extreme patriarchal backlash to follow. Federici sees feudal society’s wretches as prone to apocalyptic movements, trying to create a new society, and women were drawn to these in large numbers, taking leading roles including in some of the uprisings (food riots a speciality). The liberation theology of its day, these heresies were persecuted by a militant, intolerant Church which responded with crusades, burnings at stake, torture, inquisitions, anonymous charges (to which women were particularly vulnerable). Witch-hunters were apparently quite focused on contraception and abortion practices, which were used as part of some heretic movement’s attempted sexual revolutions; midwives and pregnant women were mistrusted, spies informed on their activities, and male doctors took over. Women’s work was divided, downgraded and domesticated.

Federici makes a lot of good points, brings in much useful historical evidence to support the book’s well-reasoned arguments, although I think we have to regard the hypothesis that the witch-hunt was part of a campaign to harness reproduction to populate the workforce as unproven. In other respects, on labour, on rebel movements, and on colonialism, I find the book convincingly argued.

One of Silvia Federici’s main projects in her book is to free ‘women’ from the biological determinism that emanates as an ideology of capitalist relations of production and establish it instead as a transgressive category of critical analysis in the culture war against that ideology.

Her method is a Marxist-feminist one. She presents a historical analysis of contemporary changes in the relation of women’s work to the economy, the development of the bourgeois ideology of sexual differentiation in early modern times, and the alliance between the religious institutions and the emerging nation-states in the 16th and 17th centuries to repress autonomy and sexuality as a way of consolidating control over the republic.

For Federici, gender and sexuality are not purely a sociological reality and biological reality respectively, but a specification of our productive relations under capitalism; a division of labour that can be manipulated as a precondition for the production of surplus-value in the development of capitalist relations of private property and the split between commodity production for exchange in the market and production for use in the household.