Paolozzi & the Arandora Star shine on Kenmure Street

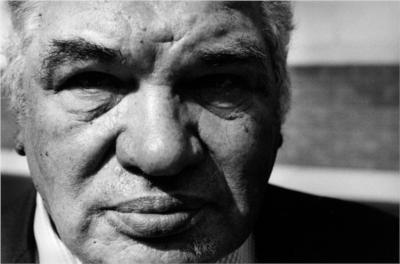

There are great works of art that emerge from tragedy. Some, like Guernika by Picasso, bring the full horrors to life, in a cautionary immortality. Other artists seek to do something even more radical with their work – to heal, to forgive, despite it all. There is one such sculpture in Edinburgh, at the top of Leith Walk. It is a giant foot, a giant hand, and an ankle. They combine to form one piece of art, called the Manuscript of Montecassino, by Leither, sculptor & Scots-Italian, Eduardo Paolozzi.

Not many people know the story behind them. But if you ever wondered why you often hear the ethnic identity / description “Scots Italian”, but never ever “British Italian” or “Italian Brit”, then you’ll find the answer in here. It’s a story about the Scots-Italian experience, about a tragedy aboard a ship called the Arandora Star, with question marks over Churchill, and it’s about the importance of forgiveness in extremis, one world class sculptor, and a gentle decency and internationalism.

The hand, the foot, the ankle. They sit at the top of Leith Walk. They were commissioned by Sir Tom Farmer and they were a labour of love for [Sir] Eduardo Paolozzi. Here’s the backstory.

The Paolozzi’s, like my grandmother Viola Lamarra’s family, and like the Nardini’s and Crolla’s, the Contini’s, Valvona’s, Boni’s and Capaldi’s, all emigrated to Scotland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, from a handful of tiny villages in a gorgeous valley near Monte Cassino. It’s halfway between Rome and Naples, but tucked in the remote mountains. The villages include Picinisco, Valverde, Sant’Elia Fiumerapido and Cassino itself. The emigration story we heard was of the crop failing a number of years on the trot, a flit born of necessity. The plan was not to come to Scotland but to go to the New World, as so many Southern Italians were doing. The only affordable route was via Naples to Leith (disembark), cross country to Greenock, then ship out to New York City.

On arrival in Leith, only my great grandfather, Giovanni Lamarra, spoke any English. But the seven hills, the greenery, it felt like home, and they stayed. Indeed only one family member completed the trek to the Americas. For some reason they didn’t take to NY, and ended up further yet in Vancouver.

The rest of the families settled in Scotland. My grandmother Viola and Eduardo Paolozzi were ages with each other, went to school together in Edinburgh, and this is a picture of a bunch of them (when Paolozzi and my gran would be only 3 or 4) at a Lamarra-O’Donnell wedding in Greenock, in 1927 (below). I come from the kind of family that faithfully wrote down and listed the names of everyone in a photograph, on the rear of every picture, making for a true wee treasure to stumble upon.

By the time Viola and Eduardo were in their teens, Scotland was their home, and their home liked them. One great grandfather of mine had taken enormous pride in being one of the original debenture holders for the “new” grandstand constructed at Easter Road in 1924, and we still have the same seats today, 97 years later.

But by the late 1930’s, things had changed. And when Mussolini declared war on the UK in 1940, it led to Italian men suffering Internment. Thousands were locked up in HMPs Saughton & Barlinnie, including Paolozzi himself (who spent 3 months inside Edinburgh prison, simply for being Italian).

Eduardo’s father, grandfather and uncle fared much worse though.

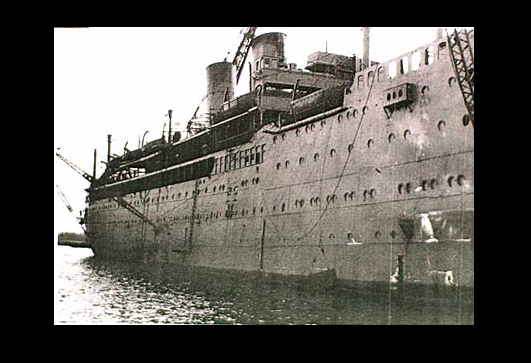

They were rounded up and, in their case, instead of facing internment in a local prison, they were told they were being shipped out to Canada, to be locked up in Canadian Internment Camps. Along with 446 UK-based Italians, they set sail on 27 June 1940 from Liverpool bound for Newfoundland on a ship called the Arandora Star (photo above). It would be the last 4 days of their lives, and many others.

The ship was not marked as a civilian ship (an oversight with a paper trail leading all the way to Winston Churchill’s office, many would contend). Once the ship left the straits between Kilberry (Argyll) and Northern Ireland, and entered into open waters, it was sunk by a German U-boat.

446 Italians lost their lives, drowned in the tragedy, including Paolozzi’s father, grandfather and uncle. The shock of the losses (and the questionable manner in which they came to be on the ship in the first place, and how it came to be sunk as a suspected warship) caused an enormous and long-lasting pall to fall over the Scots-Italian community. It was our 9/11, to put it one way.

Now, if you are Paolozzi, losing your father and grandfather, and your uncle, in those circumstances, there is a lifetime’s worth of bitterness in that story, if bitterness was your thing. But this is the point of Paolozzi’s sculpture, and its genius – the foot, the hand, the ankle, they are full of symbolism.

The Scots-Italian community regrouped, and struck an overwhelming tone of forgiveness – that Scotland is our home, it’s where we have been welcomed, and there are numerous stories from that wartime era of local neighbors in Scotland sticking up for their Scots-Italian pals (including covering for them, hiding them) while the British state was intent on implementing Internment.

Fast forward 81 years to Kenmure Street in Glasgow, and you see the parallels yet today. While the distant compassion-less robotic state computes only “Internment” or “Expulsion”, it is the local residents and neighbours who rally, who offer the human pulse, the embrace, to say “these are our friends, our neighbors, they are part of us, leave them be”. And here’s how Paolozzi expressed it.

His sculpture is scattered across three parts. And they are currently dismembered, unattached, and that is important. There is the ankle, which sits apart, and then there are the more symbolic giant foot and giant hand. And in the wake of Kenmure Street, their story will speak to many more Scots.

First of all you have the giant foot. It sits proud, immovable, enormous. It’s as big as a Home Office Immigration Unit van. But the much more gentle and cultured message it gives out is “this is where I stand, this is where we (as Scots-Italians) have planted our feet and made our roots. You know where we stand”. But sitting just nearby is the hand. And you’ll notice it is an open hand – it is not curled into a ball or a fist. Sure, it still carries the scars of war, clearly visible on it. But it remains an open hand, ready for a handshake. It’s offering a position of forgiveness, despite it all.

And the key thing is all three parts (the ankle, the giant foot that roots the community, and the open hand ready for a handshake) they are currently unattached, dismembered. And that is important because the message of the sculpture in three scattered parts is this: it takes people to bring the pieces of the story together – the proud roots, the defiant but unaggressive stance, and the implied act of forgiveness and moving on. The ingredients are there, but it takes people to make it happen.

It is ingenious in its simplicity, and in its use of art to heal the schisms that the Arandora Star.

It seems to me the perfect metaphor for Kenmure Street, and it maybe sheds light for us all on why you often hear the term “Scots-Italian” as an identity, but never British Italian or Itailan Brit.

The final aspect of the sculpture that sets it apart for me is that Paolozzi deliberately crafted it so that children in future generations, such as ours, might actively play on the scupltures – that the pieces are not distant or overly revered. He hoped there would be innocence and laughter heard, instead of the horrors of war – whether the Internment, the 446 lives lost on the Arandora Star, or indeed the 75,000 lives lost across both sides at the Battle of Monte Cassino in World War 2.

So in two major regards, the Manuscript of Montecassino sets apart Modern Scotland from contemporary Brexitland. While it is rooted in a world war two story, Paolozzi’s sculpture looks forward, with forgiveness, and an embrace, where laughter should reign in future, based on a healing story about individual local acts of kindness saving immigrant lives in Scotland. Whereas for Brexitland, World War Two is omnipresent: about triumph, superiority, a moment stuck in aspic.

It’s my individual taste, as a forward-looking internationalist, but bring me the laughter, of a clambering child, on a giant foot or an open hand, any day, over Priti Patel’s van in Kenmure St. The Scotland I know is a place that connects the immigrant foot with the open hand of friendship.

Thank you, Iain, for this life-affirming story, which chimes so well with the Kenmore Street incident. I love Paolozzi’s work and to discover the story and meaning behind these sculptures is heart warming. And I couldn’t agree more with your final paragraph.

Re Palaozzi, I recall his appearance many years ago on Desert Island Discs. He repeatedly referred to Edinburgh as being in England and not once was he corrected by the awful Southron Sue Lawley.

What on earth were you doing, listening to that dreadful Desert Island Discs on the b*st*rd*n BBC? Are you English or what?

Well I just listened to it and nowhere does he say Edinburgh is in England so Lawley had no reason to correct him. When he does mention England it is in reference to either living there (which he did for most of his life) or being ‘from’ there in that sense. Perhaps the galling thing is he never refers to himself as Scottish.

One interesting point he makes about his father and uncles is one of the problems was that were all part of a fascist club in Edinburgh when Italy declared war on the UK in 1940. Now he does not say they were bad men, they were just brought up with fascism in Italy but they kept it going once in Scotland.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p0093zpm

I have always been intrigued by his one acting role in a shortish feature film called ‘Together’, made by Italian Lorenza Mazzetti with considerable help from Lindsay Anderson in 1958 (one of the Free Cinema films). It is a flawed film in many ways but its depiction of post war London is mesmerising in its kind of beautiful awfulness and the film is a study of alienation mainly. The sound design is brilliant though and as a document of London’s East End and docklands of the time it is superb. It is free on the BFI website.

Thanks for the heads-up regarding ‘Together’. I like a bit of experimental film.

Thank you for digging that up; I had no idea it would still be available, but clearly my memory betrayed me somewhat. Lawley, however, always had an inbuilt smirk whenever mentioning matters Scottish. But Paolozzi definitely did not see himself as Scottish-Italian.

I always felt she had a smirk on her face about many things tbh. I was never sure if it was just a mannerism or not. She is actually quite negative about England in the episode I notice, as was Paolozzi, i.e. about the inward looking and dreary nature of the place after the war such that Paris seemed so open and vibrant after the Germans left, both picking up where they left off before the war, he suggests. At some point the idea of Paris being the centre of the ‘European cultural universe’ dissipated though and it is far from that now. It shifted to London maybe for a while but that is now over too. I guess these things never stay the same for that long. It was Berlin for ages but not sure about now – Covid has messed everything up. Maybe it could be Edinburgh or Glasgow soon?! (Actually I’m not sure it could be Edinburgh as despite all it offers, it is just too much of a tourist money-spinner)

Hi Callum. I’m not English but I have lived there most of my life. That broadcast was long before BBC Scotland’s channel enabled me to listen and watch Scottish matters.

Well, in my book, that makes you English, since England’s is the civic life in which you currently participate (e.g. vote and pay your taxes). That would have made Paolozzi English too, for most of his life.

Dear Ian That was a brillant piece . I have always loved the sculpture but this story makes it even more relevant and loveable . I always touch it every time I pass. I will touch it even more tenderly . It is a great work of work

Such a lovely, interesting piece . Many thanks for that. Fair cheered me after reading and watching pure cynicism and cruelty in newspapers and television. More please.

Very interesting, always loved the Italian Cafes and friends I made in Parkhead, still go back and say hello, now and again! Always made to feel welcome! Glasgow is big enough for all!

‘It seems to me the perfect metaphor for Kenmure Street, and it maybe sheds light for us all on why you often hear the term “Scots-Italian” as an identity, but never British Italian or Italian Brit.’

You mean the Anglo-Italians, with whom Paolozzi identified after he moved to London in 1944?

BTW the Church of St Peter, on Clerkenwell Road, at the heart of Anglo-Italian London, was modelled on San Crisogono in Rome and houses a memorial to the 470 Italian men who died aboard the SS Arandora Star. Of course, not to be outdone, Scotland has its own memorial garden, which Alex Salmond opened in 2011 as ‘a magnificent tribute… to the part the Scots-Italian community plays in the rich tartan fabric of our nation’.

I think that Alex Salmond was being diplomatic when he described the memorial to the victims of the Arandora Star as ‘magnificent.’

The memorial, beside Glasgow’s Catholic Cathedral, is rather tacky. Those who lost their life deserve something better.

Tacky? Do you think? I find Giulia Testa’s garden a beautiful space to inhabit. I particularly enjoy the companionship of the 200-year old olive tree, gifted by the people of Tuscany as a token of forgiveness, and how it’s mirrored in the plinths. On a sunny day, you can watch incredibly dramatic reflections being cast from the plinths onto the grass and pavement below. You can sit and listen to the running stream or wander the labyrinth of mirrors and reflections, reading the engraved poetry, including the poetry of the names of those who drowned.

As Mario Conti said in his address at the opening of the garden; it’s a fitting remembrance of their (the Italians’) rejection from the Scottish community.

Having visited the memorial a couple of times, I disagree. Mario Conti was one of the prime movers behind the memorial and might not be an impartial witness when assessing it. The site chosen struck me as ill-advised. That part of Glasgow is run down and has been for decades.

At roughly the same time, the cathedral next door was renovated and it was a success. Whether it was worth the £5 million it cost is another matter.

We clearly don’t share the same aesthetic, florian.

SCRIP O MONTE CASSINO

this smaa scrip gangs alane

owre shad o heichts an glens

seikin oot the benedictine ruif

whaur rest awaits

the wearie cam ti fuind green herbs an breid

pace an brither-luve…

christ’s pace on ilka heid!

What a great, insightful article. I am so glad to learn the story and will make a special trip to see the sculptures and spend time there. Then the next thing will be to walk to Valvona and Crolla for coffee and a cake.

‘The emigration story we heard was of the crop failing a number of years on the trot, a flit born of necessity. The plan was not to come to Scotland but to go to the New World, as so many Southern Italians were doing. The only affordable route was via Naples to Leith (disembark), cross country to Greenock, then ship out to New York City.’

The migration story I heard was of my great-grandmother on my mother’s side coming via Klaipėda to Leith, en route via Greenock to New York.

Her husband took ill and died in Leith, and my teenage great-grandmother embarked on the transient life of a field-hand, which took her from hiring fair to hiring fair, down through the Lothians, and into the Borders. She ended up having five children – four boys and my grandmother – none of whom had a father to own them. Her eldest son was killed at Gallipoli during the First World War, but the local war memorial committee refused to put his name on the memorial after the war because he was ‘German’, Jewish, and illegitimate. Her second-eldest – a pleuman – came home from France with shell-shock, and thereafter ‘cudna be left alane wi the bairns’. Her two younger sons grew ZZ Top beards and lived as shepherds in the fastnesses of the Tweedsmuir hills, while my grandmother followed her into the precarity of outdoor service.

She died of old age during the Second World War, having been taken in by my grandmother and HER four faitherless bairns, and having narrowly missed being interned in her decrepitude. In her last days, the local postmistress kept coming to the house to check on her ration book. Apparently, my grandmother threw it in her face when she arrived to collect it just an hour or so after my great-grandmother had rattled her last. My grannie hissed and spat at a lot of the villagers, right up until her death in 1981; they were douce but not very nice people.

I’m happy to report, though. that my children are of the first generation to have reached adulthood without the moral taint of my ‘German’, Jewish great-grandmother on their socially constructed characters. Nobody ‘kens’ her anymore. They’ve attained the cardinal Scottish virtue of respectability. Assimilated or at last. Naturalised Scots.

They’ve attained the cardinal Scottish virtue of respectability at last. Assimilated or naturalised Scots.

If you only show compassion to those who have demonstrated compassion, is that not missing the point of compassion?

Compassion has a point?

That’s teleological talk, and God is dead. There are no final causes.

Compassion is just sitting in the cloister, suffering with all those who drowned when the Arandora Star sank, albeit only vicariously. It has no higher purpose.

Weil, so it goes. This is painful, but reminds me of the recent war in Ireland, now suspended, but not ended. It only takes a small amount of stupidity and everything non essential gets “Ditched”. That includes basic humanity, things like art and culture, as the small local group of artists and intellectuals are targeted, as they were in in the Northern War, and as part of a deliberate stratergy by the Unionist fascists and ther UK military. It has taken a long struggle for it all to re-emerge from that war. Many had to flee. Why doi I make this point? Because it can happen in Scotland, if the liberation struggle there turns dangerous, people need to know what to expect. Also, much of the power and resources for art and culture in Scotland, are ultimately controlled by the Unionist clique there, and would be vunerable in such a situation. In the South of Ireland, during the post 1916 liberation struggle, many had to keep low profiles, or leave. Irish culture was threadbare for years afterwards, and also split by the civil war. All of this springs from a national liberation struggle. The situation in Scotland is now ominously trending towards the same destination. I have not the slightest doubt that if the present Scottish Goverment tries to hold a new referendum, evil things will happen. It will certainly be suppressed and the situation will become a repeat of the Catalan struggle. Think about this. I have been. What goes through my Irish mind is that all liberation struggles eventually lead to the same grim path. Do not think that the london Goverment will not do whatever is required to keep things getting “”Out of control”.

Sometime in the present session of the Scottish Parliament, Sturgeon now has a mass vote from the last election, a mandate. The clock is ticking. Like a political time bomb. The art and intellectual community in Scotland need to think about its situation. Very carefully. In a national struggle, they have a vital part to play. Now is not too early to start that process. All comments gratefully recieved, even rude ones. (Its called a debate. Scottish ones tend to be a bit raw, but truthful).