Are You an Island?

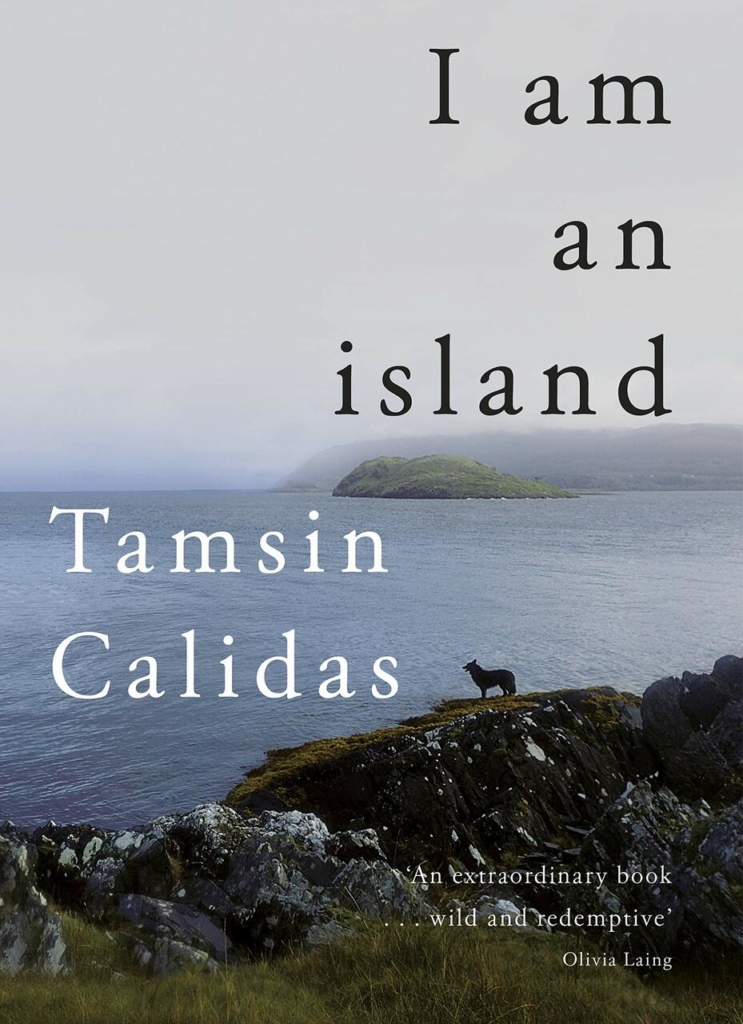

Book review: Tamsin Calidas’s I Am an Island.

John Donne’s 1624 book, No Man is an Island, is about the interpersonal relationships of humans and their place in the circle of life. Donne’s writings often ventured towards the philosophical, exploring the tenets of behavioural psychology which would not be classed as a science of their own for a few more centuries. I wonder if he had enough insight into the human psyche to imagine the possibility that, by law of reverse psychology, someone would one day write a book called I am an Island with a very different outlook on relationships.

About a century after Donne’s publication, another English writer published a novel which still resonates in the collective cultural unconscious of the western world: Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Arguably, it begat the whole genre of adventure literature – human versus wilderness, stranded on an island, foraging and crafting one’s way to survival. When Robinson Crusoe encounters the island’s natives, we understand Defoe’s depiction of them as savage cannibals to be the product of Defoe’s time; the colonial, British mindset when encountering the Other. We file it together with other portrayals of indigenous peoples which we no longer find acceptable in the 21st century, next to Heart of Darkness and dime westerns about Buffalo Bill chasing redskins across the plains. For some reason, however, the 2020 publication of I Am an Island slipped past the limelight and managed to avoid similar scrutiny – aside from Amy Liptrot’s sharp critique in The Spectator.

Perhaps ‘slipping past the limelight’ is not the correct expression for a book which achieved Sunday Times Bestseller status and was dubbed ‘Memoir of the Year 2020’ by Vogue. It is clear, even from the book’s reviews on Amazon or Goodreads, that it has been received extremely well by its target demographic. The long months of lockdown had urbanites longing for an escape; for those who had forgotten a life existed outside the office, lockdown also signified the start of a renewed search for purpose in life. I Am an Island’s dustjacket draws readers in, promising the life story of one middle-class Londoner who managed just that: an escape to the countryside and a purpose in life.

The book’s author, Tamsin Calidas, is a good writer, and the highly emotive, descriptive prose is one of the reasons behind the book’s success. Its style, where nothing is too personal, is in many ways its greatest strength. The book left me feeling sorry for the author. The issues that she struggled with: spousal infidelity, infertility, traumatic accidents, financial destitution, and the hopelessness which leads to suicidal thoughts or attempts, are described in a deeply emotive way which I, and many other readers, clearly related to. The author’s description of the feelings of isolation which often accompany such difficult moments in a person’s life is haunting; the partial solace she finds in the natural world is thought-provoking. Unfortunately, no amount of invigoration pouring out of the passages where the author goes swimming in icy temperatures could mask the work’s greatest flaw: a pathological lack of self-awareness.

If this entire response feels too radical, it is merely because the book’s publication date coincides with a time in history when very serious questions are being posed about the future of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the tourism-related issues which have been building up in rural communities for years. Despite pleas from Highland and Island communities – who, collectively, had access to about 30 respirators when the virus broke out – many understandably desperate city-dwellers yearned for a getaway and travelled northwards despite being asked not to. The Soillse Report (The Gaelic Crisis in the Vernacular Community, 2020) says that Gaelic, as a community language, is dying; the reasons are complex, but the fact that youth from the islands where Gaelic is still spoken by a majority cannot afford to live there, is certainly not helping. The rapid aging of Scotland’s rural populations has only been exacerbated, which is bad news both for the Highlands’ indigenous language as well as indigenous land practices – a 2018 report says that 45% of crofters are aged 65 and over, while only 3% are aged under 35. However, there has been a paradigm shift in the younger generation; whether it has been caused by a rising green consciousness or disillusionment with big city life, more youngsters want to return to their Highland homes after finishing their education down south. Perhaps, in part, the digital revolution has made it easier for people living in remote communities to start a business and trade with the whole country, and even the whole world. Indeed, those of the UK’s desk-job workers who can afford it have been moving out of London and other giant population clusters in record numbers. While demand for rural properties may have spiked, the last year is only symptomatic of a process which has been going on for decades. Island youth have aptly called this a new wave of economic clearance and formed grassroots group to make their voices heard, such as Iomairt an Eilein. The housing crisis may have locked my entire age group out of ever owning a home – and my Hebridean pals, earning Hebridean wages, are tired of rejection when their price offers are competing against big London money.

And it is exactly from this moneyed, high society of London that Tamsin Calidas, the author of I am an Island, came to Lismore. Before I delve into the author’s wilful ignorance of the issues plaguing island communities, though, let us set the scene. Let us start at the beginning.

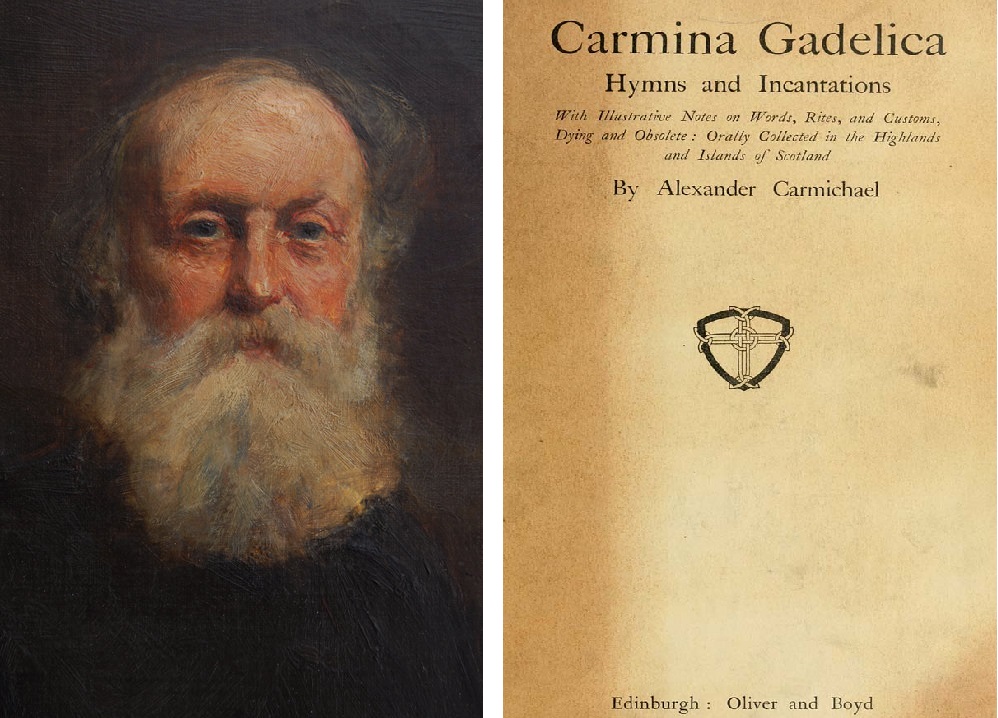

Nothing raises red flags to Gaelic speakers as much as a mystical Celtic quote at the start of a book about an English person traveling to the Hebrides. I wanted to give the author a chance, though – being born south of the border does not equal turning into Boswell and Johnson upon reaching the west coast. I am an Island opens with a fragment of what the author calls ‘The Descent of Brighid’ from the Carmina Gadelica – a famous, multi-tome collection of poems, prayers, charms and incantations that Gaelic folklorist Alexander Carmichael collected from 1860 to 1909. The National Library of Scotland has digitised Carmichael’s collection, but I struggled to find the quote. After a little digging, I found Banas Brìghde no Molta Brìghde (‘The Womanhood of Brigit or Praises of Brigit’ in English) in the 3rd volume of Carmina Gadelica, collected from Peigidh NicCarmaig of Lochboisdale, South Uist. Tamsin Calidas’ readers could have been told a correct title and what volume of Carmichael’s work to look in, but you cannot expect a memoir to use precise referencing for its big opening quote, and the author may be forgiven for this. Among the four lines quoted by Calidas we find the following two: ‘Cha leg a ’ghealch mo planadh / Cha teid usage a bhathadh dhomh’, riddled with typos. The translations given are ‘nor moon shall blanch me, nor water shall drown me’, but even Duolingo-level learners (and Google Translate, for that matter) could sense that something is amiss here. It becomes clear, at this point, that no Gaelic speakers were asked to proofread this excerpt before it was put in the book; in fact, it looks like the author’s computer autocorrected uisge (water in Gaelic) to usage. Poor effort, but maybe the publisher was keen to get the book out quickly to hit the lockdown market and there simply was not enough time to find one of those rare mythical creatures who can speak Gaelic. Maybe Tamsin just roughly typed out what she found in a library copy of Carmina Gadelica and put it in her book?

The problem is that the original simply does not go like that. ‘Ni teintera teine mi’, the first line quoted by Calidas, is supposedly ‘no fire shall burn me’ in English. But the line does not exist in Carmichael’s work; while the initial ni makes me suspect that it is actually bad Irish. Already the breadcrumb trail is leading us away from the Carmina Gadelica towards something taken from celticmyths.com; the atmosphere of kitsch is difficult to dispel when the book starts exploring themes of revering deer “for their shamanic strength” and “honouring old beliefs, rites and rituals” near its end. But could this (at best) ignorant mistake or (at worst) blatant cultural appropriation be excused if the author, who had moved to Lismore, just wanted to showcase the work of one of the island’s most famous inhabitants, Alexander Carmichael or Alasdair Gilleasbaig MacGilleMhìcheil? Maybe – but we will never know, as the author makes no connection between this quote, Carmichael, and her new island home.

Alexander Carmichael and his magnum opus, the Carmina Gadelica. Portrait by William Skeoch Cumming. Both images are in the public domain.

How does the process of making herself at home on the island go, then? It is quite clearly a culture shock (“We are well travelled, but this island feels more remote in its landscape than any other place we have travelled to”, page 23). The Londoner walks along the single-track road and passing cars slow down to “scrutinize her through steamed-up windows” – an unnecessarily sinister description of folk trying to see whether the person they are passing is their neighbour/boss/auntie/all-of-the-above and they should sound the horn or not. Two local crofters walk across the land she had just acquired a tenancy of (to greet their new neighbour, in their own words) but the interaction quickly becomes confrontational. A memoir is, of course, personal – but the author’s unwillingness to share the background as to why conversations turn sour throughout the entire book feels disingenuous, like something is missing. In the case of this early confrontation with the crofters, Tamsin’s refusal to make the neighbours welcome on her property immediately pits their right to roam at odds with her clearly fragile sense of ownership over the land she and her ex-husband bought. “No, this is our croft, mine and Rab’s. We just bought it” says the author. The neighbour responds, “Aye, so you did. Well, you can call it what you like, but this croft has always been Hector’s croft.” The author’s own italics are meant to make readers sympathise with the wronged newcomer, desperate to find their footing on the island. In reality, Tamsin’s insistence on it being her croft takes an unintentional stab at another feature of the Highlands – place-names. Despite the desolation caused by second homes standing empty in what were once thriving communities, place-names are still one of the ways in which history – sometimes hundreds of years old – manifests in the present day.

Iona’s Gàradh Eachainn Òig (Young Hector’s Enclosure) allegedly hearkens back to young Hector, a cadet of the MacLeans of Duart, linking today’s hillside to hundreds of years of clan history. Àirigh Dhòmhnaill Chaim (Crooked Donald’s Shieling) is an old shieling site on Lewis, but was used as a camp site during the Pàirc Deer Raid of 1887; and so both the raid and Dòmhnall Cam are remembered. Back on Lismore, Hector may have been the tenant who last lived in the croft before Tamsin’s arrival, or he may well have lived there two hundred years ago; regardless, there is clearly a reason why the crofters insist on calling it Hector’s croft and it probably has nothing to do with Tamsin Calidas.

Sign to the memorial commemorating the Pàirc Deer Raid of 1887 with the township of Balallan (Alan’s Town – another person commemorated in place-names) in the background, Isle of Lewis. © ‘Arnish Lighthouse’ blog archive

This is not the only time in the course of I am an Island that the author comes off as deliberately insensitive – especially in relation to land. On page 39, she states that on the island, “kinship and soil are fiercely defended territories” – but offers no insight into historical or contemporary reasons for the Gàidhealtachd being a territorial, kin-based society. On page 130, an expansion on the island’s culture – a “feudal” society, with “wearisome, coercive” traditions in Calidas’ own words – is offered: its “culture is rooted in a landscape where soil dominance and ownership are paramount”, especially as an assertion of masculinity in a hunter-gatherer dichotomy of gender roles. The author feels her style of working her croft, especially as a single woman, “challenges” the island’s deeply patriarchal, rigid social order. Throughout the book, the reader is told that this is the root of all animosities between herself and the ‘natives’. But what if gender, or even what she does with the land, have nothing to do with it?

When Calidas is confronted with the words: “Bought this wee place as well, did you? Conquered with the chequebook where you failed with the sword” the moment seems perfect to explore why relations between natives and incomers – especially wealthy ones from the south – can be so tense. When another islander is said to have commented “We were going to buy this croft” regarding Calidas’ purchase, the author’s instinct is to question why the person did not put an offer in themselves back when the croft was on the market. The idea of Tamsin Calidas’ 22 acres and ruined-cottage-in-need-of-complete-renovation being beyond the financial grasp of a native Lismorian is never explored. Indeed, despite tying various social justice issues like racism and misogyny in with the narrative of her memoir, the author has blinkers on when perfect opportunities to discuss the land question in the Highlands come up. The experience of Calidas’ father in apartheid-era South Africa; having relatives in Hong Kong – these personal details almost beg to be the stepping stones to a discussion about the British Empire’s hands stretching from London out to its peripheries, whether just past Oban or on the other side of the ocean.

Between 1841-1881, the population of Lismore was reduced from 1400 to 621. Here is one of many ruined dwellings at the deserted township of Coille nam Bàrd (wood of the bards), Lismore. ©Iosua Mac Roibeirt, all rights reserved.

If this required more self-reflection than the author was prepared to provide readers with, then some acknowledgement of class, surely, was the least we were going to get? I am an Island makes it clear that getting one’s foot onto the property ladder does not provide a magical shield against financial destitution. On page 59, Tamsin admits that “regardless of [her] dreams of living simply it is not possible to live solely off the land while [she is] still setting up and trying to finish the house… sustainability comes at an eye-watering cost”. When her husband leaves, she finds herself in a precarious position, leading to months of nourishing herself on tree bark and other foods foraged from the island – no doubt a shock to an ex-yuppie with a career in journalism and broadcasting behind her. Betrayed by her husband and broke, the author remarks on her failure to establish meaningful relationships with anybody on the island. One day marks a turning point in Calidas’ island life – the day she picks up the phone and hears from Cristall, “a woman with an educated English accent” (page 64). A friendship quickly blossoms between them; Tamsin finds herself among erudite society once again and no longer feels alone. Calidas easily accepts kindness and support from Cristall, while rejecting it from anybody else. On page 132, she says: “even kindness can be double-edged. It may be offered freely and genuinely, or it may be laid with a tripwire and a snare. I am wary of accepting favours and help. Kindness that comes with strings attached can be subtly coercive. It creates its own debts, dependencies and bonds. Gratitude, its reward, has its own fragile weight and springs.” It is precisely the vulnerability required to ask a neighbour for help – without quantifying or commodifying acts of kindness, and without wariness of ‘tripwire and snares’ – that builds càirdeas (fellowship) and trust. To me, trust and kindness are the wind which carry the ship of community forward, cutting across oceans of division: ‘native’ and ‘incomer’, rich and poor, old and young.

There is a level of erosion at work, though, and the culture and language are more subtle now – like the shapes of feannagan or ‘lazy-beds’ on a hillside, elusive under bracken to the untrained eye; like a ‘bùrach’ buried in an otherwise English sentence. They are what attracted me to the islands, but I know that not everybody feels the way I do about Gaelic, and I have to accept that. What I cannot accept is celebrating the demographic change in this region with the implication that there was something wrong with the way Lismore was before the “influx of international volunteers”, before the “quiet yet burgeoning tourism”, and before Tamsin Calidas’ brought her “own traditions” there, as page 255 suggests. I feel that the only appropriate response here is to paraphrase the brilliant song Cànan nan Gàidheal by Murdo Macfarlane, the Melbost Bard: many a time throughout history have people lit the candles at a wake for Gaelic, but the language of the Gael stubbornly lives on.

It has now been seven years since I started studying the language and culture of the Highlands and Islands. I certainly have not ‘cracked’ it and continue, daily, to be surprised. Mostly, I am surprised by how open Highlanders are to the idea of some crazy Polack going through the bother of learning Gaelic from scratch and trying to make a life for himself out West. At other times, I am surprised by the depth of their roots and by their resilience in the face of every hardship that has befallen and been imposed upon their nation. Many of the young Gaels or Highlanders – however which way they might identify themselves – whom I know are not contented with standing by while more clueless narratives are spun about their homeland. The voices of journalists, politicians and economists who have spent at most two weeks up north on a family vacation, are still the ones making decisions on which roads should be fixed and how Gaelic should be saved. From a historical – say, an 1880s – perspective, big changes followed when Gaels’ own voices were being heard in the media. Through grassroots activism and a stream of letters received by this year’s MSP candidates for the different Highland constituencies, they are speaking: èist rinn. Listen to us.

Long before Tamsin Calidas wrote I am an Island, Highlanders were being accused of insularity and clannishness. There was a vested interest in portraying Gaels and the Gàidhealtachd as a strange living museum of constrictive traditions, as inbred and closed to the outside world. Clearly, some such opinions linger on to the present day. Angry glances shot at campervan colonnades are misunderstood as hostility or xenophobia, ignoring the very real frustration of seeing another 3.5 tonne motorhome deepen a pothole that the Council have neglected to fix for a decade. These misunderstandings might lead the cynics to see the concerns about the Highland housing crisis as self-serving or inherently unwelcoming to outsiders, but I have news for them. Islanders know full well that ‘incomers’ means wealthy retirees wanting to sketch the landscape and run a B&B by the beach, but it also – perhaps even more so – means NHS workers, delivery drivers, teachers, and new blood in the community. There is only a crisis because the market in the Highlands and Islands is in a state of utter imbalance, totally skewed towards those with a lifetime’s worth of savings on their side, regardless of origin.

Collective action has always been difficult in the Highlands and Islands because of the distance and terrain between individual townships, especially after half of them were emptied. The scales are tipping, though, as more and more issues that were once endemic to Skye or the Outer Isles begin to affect the mainland and seem to be spreading. Thankfully, Highlanders are not islands – they stand together on many of the issues that really matter today.

Thoughtful piece, raising important issues; thank you.

Good review but the opening paragraph is nonsense – Donne did not publish a book of that title its a quote from a meditation in ‘Devotions on Emergent Occasions’ and the import of the passage is theological not psychology – marrs an otherwise excellent review

I am very glad to see an exposure of a neo-colonial genre of writing that seems to appeal to the metropolitan well-to-do and and self-absorbed, in search of vicarious relief from ontological boredom.

The disaster of the micro-capitalism that is nodded towards in this case study can mostly be dated back to the Crofting Reform (Scotland) Act 1976. This introduced a crofter’s right to buy: to de-croft (i.e. privatise) what had been heritable regulated leaseholds and turn them into deregulated freeholds, thereby losing access to agricultural and related housing grants, but rendering “the property” more marketable.

A subsequent hands-off approach from legislators has meant that even continuing leasehold crofts have seen escalated capital appreciation to market prices that pitch them far outwith their local honest-livelihood value.

The cycle is vicious, divisive and eviscerating of community cohesion. A typical case I know of had the elder brother, who had invested his life far away from the isles, inheriting the house and croft leasehold, and selling them on to the highest bidder. These, a couple from “away”, from the Deep South, who specialise in buying places to do them up (or “over”?) for the holiday market, and probably permanently de-crofting before selling on. The poor sister now can’t afford to live in the community of her native childhood. She rents in Glasgow, moving from flat to flat, unable to express the gifts that she could bring to her Gaelic community of origin.

Ironically, the 1976 Act was brought in by a Labour government as an early but I’ll-conceived attempt at land reform. Being an individualistic approach, it merely amplifies and legitimises deregulated free-market private property including leasehold market capitalisation. Only those with what locals politely speak of as “economic advantage” can hope to get a foothold.

What is the solution? I consider that we’ve failed to understand widely enough the potential richness and revolutionary nature of community landholding. A community land trust holds crofting leaseholds for the benefit of the whole, not just for individuals. It does so democratically accountable to itself: to its own locally resident membership. Crofting communities now have the power to buy out their private landlords and self-govern if they want to. Watch out for the forthcoming Islands Book Trust book “A Long and Tangled Saga” by Bob Chambers, documenting some of the ins and outs of this with the Pairc Trust.

De-crofting is now covered (I think) by the Crofters (Scotland) Act 1993. That measure should be terminated. Existing de-crofted crofts should be subjected to planning and local taxation constraints that would incline towards limiting capital values in ways that would privilege year-round domestic residence and, in the wide sense, a crofting way of life. Landholding by land trusts should be considered the norm.

Is something along such lines likely in the future? That will depend on whose cries are heard the loudest and most effectively. The cries of those who have converted crofting tenure towards micro-capitalist ends? Or those of whole communities, that see the spirit dying – that “spiorad a’ charthannais” – and know that now is the moment to face that ancient option: “I set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life … that thou mayest dwell in the land” – Deuteronomy (oh yes!) 30:19-20.

(Caveat: I am not a lawyer. These points are of principle and do not imply a current knowledge of complex areas of law.)

Powerful comment and excellent insight.

Selling off crofts to the highest bidder on the open market (let’s be honest, almost always from Edinburgh or London or furth of these shores) reminds me in some ways of the right to buy and the sale of council houses. Some are now out of reach of the very people they were built for.

Council houses and crofting land were won by generations of collective action by our forebears fighting for a more secure, equitable existence.

The question for me is: are crofts and council homes to be held by people in trust for the next generations of our families and for the wider community? Or are they assets which can be flipped and sold in the free market to anybody and everybody with enough inherited wealth or inflated city property wealth, no matter their involvement with the local community, no matter their intentions?

For what did our forebears agitate in the 19th century? For what did they organise and demand security after their brothers perished in vast numbers in trenches fighting colonial and imperial wars?

So that folk could punt it to a rich person from Edinburgh or London with inherited wealth to turn into an airbnb?

I’m not myself the product of a council house or croft but the generation before me were. It disgusts me to see open market principles pulling about the threads and fabric of these hard won securities.

I believe crofting legislation has now been amended to include certain limited areas in Arran and Bute.

I will be interested to see what might happen there, if anything.

This seems to me to be a matter which the Scottish Land Commission needs to address.

Interesting comments below about land ownership. The Scottish Government needs to have more courage than it so far has shown, to deal with the big picture.

As to Lismore, the residents here, both old and new, have kept a dignified silence about this publication as have I but I’d like to share with you my experience of being a new resident on this island. I arrived at about the same time as the author. My husband and I started a market garden (I supplemented our income with a bit of teaching) 4 years later, I was alone. A very aggressive brain tumour killed my husband within the space of 8 weeks.

From the start, we were welcomed into the community as a whole, and, when he died, I was offered sensitive support. In short, I don’t recognise the Lismore portrayed in this book. Sure, there are unfriendly people here, there are people with their own problems and darknesses, there’s a deep sense of history of family and land that could be interpreted as exclusive . In the words of the late Donald Black “Each ruin, each knoll carries some tale, some secret tradition unique to that spot”.

There is also a profound love of the place by people who have lived here for generations. That love is very infectious.

Lismore needs another book. I don’t feel that I’ve lived here long enough to write it!

If I could say with great respect for your circumstances, losing a beloved husband to illness is not the same as a spouse who is cheating under the eyes of the community with everyone in the know, and then leaving, leaving Tamsin to try to manage her animals and her land and half finished property on her own. As an older woman, (complex background, not suitable for here) living alone, I’ve often encountered, in the small rural communities I’ve lived in, the sense of being an anomaly. I don’t have grown up kids and grandkids visiting, I don’t have chatty elderly friends dropping round, I’ve got a ‘smart’ voice (no cash I hasten to add), and don’t fit in anywhere. The politest description I’ve heard of myself, directed at me, nicely, has been ‘eccentric’, though I’m not sure what I’ve said or done to deserve that. Been interested in ideas? In the natural world? In the wider world? Not just the grandkids and the Friday trip to the Chinese1 I can entirely identify with Tamsin’s situation, her unwillingness to relinquish her home that she’s fought for for so long, her grief at the loss of the identity she has had to abandon, and her courage.

What interesting comments on land tenure. I write this from Sark, one of the smaller Channel Islands with a population of just 500. All flourishing small communities struggle to provide affordable housing for local people. That underlies a lot of the social tensions described in Tamsin Calidas’s book. Sark has stumbled on a solution, almost by accident. In 1976 a Housing Law was introduced to discourage new development. All houses built since 1976 are “restricted dwellings” and can only be occupied by those who have been resident in Sark for fifteen years or more. There are now 160 restricted dwellings and the system truly does ensure that there is accommodation for local people.