Reimagining Intimacy in Scotland

Charlie Lynch interviews Dr Tanya Cheadle, Lecturer in Gender History at the University of Glasgow (@TanyaCheadle) about her new book Sexual Progressives, Reimagining Intimacy in Scotland 1880-1914, (Manchester University Press, 2020).

Sexual Progressives’ is a collective biography of a group of feminists and socialists who campaigned against the moral conservatism of the Victorian period. Could you give us an introduction to them and your new book?

Scotland’s sexual progressives were a loose collective of middle-class reformers who, for a sustained period in the 1890s and 1900s, campaigned against what they perceived to be the hypocrisies of conventional Victorian attitudes towards sexuality. These attitudes were personified in the figure of Mrs. Grundy, a satirical figure who represented all that was respectable, staid and proper, in contrast to the utopian vision of loving, respectful and egalitarian unions which animated the sexual progressives. They had a range of causes, including marriage reform, the provision of information on birth control, the overturning of the sexual double standard (which forgave men for sexual indiscretions but punished women), better treatment of sex workers, and a more ‘scientific’ and empathetic approach to homosexuality. Their political affiliations varied, although most were feminists and socialists of some description, and all ultimately turned their backs on the Presbyterian religion of their childhoods, instead becoming secularists, positivists, Christian mystics or occultists. Indeed, breaking with the Kirk appears to have been a necessary precursor to their adoption of unconventional ideas about sex. My book examines their lives and work, linking both to wider, transnational conversations about politics, faith and sexuality taking place in Scotland, England and America.

How did you come to this research topic? Was your engagement with it over the years influenced or affected by contemporary events? What kind of sources did you use?

I have always been drawn to this period as a time in which progressive change seemed possible and imminent. The novelist George Gissing referred to it as an era of ‘sexual anarchy’, when New Women novelists, such as Sarah Grand and Mona Caird, and decadent writers and artists, like Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley, were making respectable people nervous. Before my research, we knew a good deal about London sex reformers, and those working in the English provinces and in Ireland, but very little about Scottish networks. I wanted to explore not just the progressives’ published work and their activism, but how it intersected with their intimate lives; as second wave feminism taught us, the personal is always political. Letters, diaries and memoirs were therefore critical sources. Some were easy to find, with an extensive cache of Patrick Geddes’s letters housed at the National Library of Scotland and the University of Strathclyde. Others required more detective work, with papers relating to Bella Pearce buried within those of Thomas Lake Harris, the Californian-based Christian sexual mystic and head of the utopian organisation the ‘Brotherhood of the New Life’, who was revered by Bella and her husband Charles. In 1903, Harris visited the couple at their villa in Langside in Glasgow, after receiving a divine revelation to ‘go forth and bear the message to the world’. The diary written by Harris’s wife, along with letters from Bella and the Pearces’ housekeeper, contain suggestive vignettes of their everyday lives, including how Bella and Charles answered to the soubriquets ‘Lady Bella’ and ‘Sir Charles Steadfast Strong’ and how, according to the recollections of their housekeeper, ‘quite often while we were at breakfast the Fairies would speak through Mr Harris’. The Harris’s returned to America after three months, delighted by their hosts, whom they found ‘staunch and true to the Core’, but disappointed with the spiritual condition of Scots in general, who seemed ‘fastened into their old conditions’. Nonetheless, Harris and his wife did take one new convert home, sixty-two-year-old Jessie Donaldson, described as ‘a great acquisition, a ripe, rich soul, weighs about 200lbs and is 6.3 and a fine pianist.’

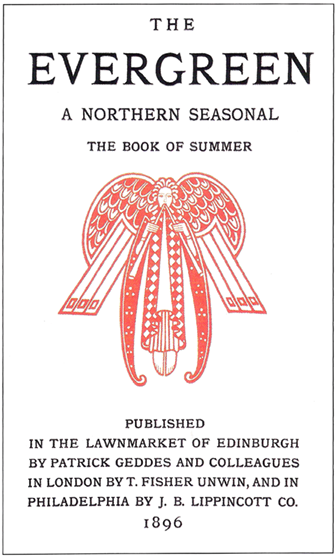

Published works were another important source for the book, including birth control pamphlets, sociological treatises, popular science books, utopian novels, and articles in feminist, socialist and avant-garde periodicals, including Keir Hardie’s newspaper the Labour Leader, and the journal of Celtic Revival, The Evergreen, published in Edinburgh by Patrick Geddes & Colleagues. In terms of how my engagement with my research is affected by contemporary events, I would say that I write as an intersectional feminist academic based at the Centre for Gender History at the University of Glasgow in 2021, and that this standpoint necessarily influences my sifting and interpreting of traces of the past.

What struck me when reading the book was the extent to which the lifestyles and reforming aspirations of the progressives were constrained by the sexual culture they inhabited. Certainly, by the standards of the more recent past much of this seems tame, while the culture feels alien and peculiar. What can this tell us about modernity and the history of sexualities?

There is a quote I like from a fantastic book on this period by cultural historian Judith Walkowitz, called City of Dreadful Delight. She states that women in history are ‘bound imaginatively by a limited cultural repertoire’. I see it as the job of the gender historian to trace the limits of this repertoire, the parametres within which it was possible for both women and men to act, think and feel. Because these parametres will differ from our own, the past can and should feel alien. I think the history of sexuality in particular requires us to be attuned to the queerness of the past, to the profound otherness of how sexual desire was understood and experienced historically, necessitating our moving away from the earlier project of identifying gay or lesbian historical forebears, however attractive this may be. Sexual desire is unruly and inchoate and often eludes attempts to describe or regulate it and our historical accounts need to reflect this.

That said, there were details in the archive which made the common humanity between myself and the sexual progressives very apparent – Anna Geddes unable to concentrate on a research trip to the library because of anxieties over childcare, or Bella Pearce excoriating a popular male socialist writer for his misogyny. In terms of what my book tells us about sexual modernity, it positions Scotland as equal participants in transnational conversations about sexuality and sexual reform happening in the 1890s and 1900s. There was no sense that Scotland’s famed reputation for dourness or prudishness inhibited these discussions; rather, characters such as Patrick Geddes saw the ‘dull prosperity’ and ‘soul-deep hypocrisy’ of Edinburgh’s respectable inhabitants as a spur to his radicalism, a sanctimoniousness against which to rebel.

You tell of the conservatism of the establishment in nineteenth century Scotland, but also of the moral conservatism of progressive organisations like the Independent Labour Party. What was going on?

Both the Independent Labour Party and the key feminist organisations of the period – the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (the constitutional suffragists) and the Women’s Social and Political Union (the militant suffragettes) – were by no means immune to the enticements of respectability. Indeed, they recognised that retaining it was vital to their electoral appeal and therefore policed a strict boundary between public discourse and private behaviour. An enduring link had been created in the public imagination between socialism and the destruction of the family by the early, utopian socialists of the 1820s and ‘30s.

Robert Owen’s Lectures on the Marriages of the Priesthood in the Old Immoral World (1835), in which he critiqued marriage, advocated divorce and proposed new, loved-based ‘marriages of Nature’, precipitated a fierce public backlash, in which socialists were typically depicted as debauched and immoral. Similarly, the personal life of Mary Wollstonecraft cast a long shadow for Scotland’s feminists, her reputation and political influence irretrievably damaged by her husband William Godwin’s posthumous tell-all memoir, which revealed her pre-marital sexual affairs. To retain respectability, any feminists or socialists in the 1890s and 1900s espousing causes seen as tangential to political aims, such as marriage reform or birth control, were distanced from the movement. The tenor of opinion within Scottish socialism can be gauged very effectively by the reaction to the Edith Lanchester affair of 1895. Lanchester was a twenty-four-year-old middle-class campaigner for the Social Democratic Federation who announced that due to her ideological opposition to marriage, she was entering a ‘free love’ relationship with her working-class partner, James Sullivan.

‘Free love’, in this period, referred to a monogamous relationship outside of marriage. Her family’s ultimately unsuccessful attempts to have her committed to an asylum for her ‘monomania on the subject of marriage’ led to widespread public commentary, horrifying some socialists. Keir Hardie expressed concern, while one correspondent to the Labour Leader stated, ‘If half a dozen young women, connected with the Socialist movement, fired up by a desire for freedom, were to emulate her example it would do the movement incalculable harm.’ Similarly, in a 1900 New Woman novel by Gertrude Dix, a financial backer of a rural commune at one point screeches ‘I knew it! … People are always talking of free love. Everyone is falling in love with everyone else, as always happens on a mixed colony.’ Such attitudes explain for the most part why Scotland’s radical voices on the Sex Question often conceptualised their reimagining of intimate relations as a future ideal, with living them in the present proving more complicated.

‘Lily Bell’ – pseudonym of Bella Pearce

A key theme of the book is how – in order to think differently about sex and intimacy – the progressives had to break with the Presbyterian religion of their childhoods. Can you give some examples of this process – and what kinds of beliefs and practices did the progressives embrace instead?

This finding was quite clear. A precondition of progressive thought on intimacy was the repudiation of orthodox Christianity. The established moral code needed to be rejected wholesale before it could be rethought anew. However, while some sex radicals might have conceptualised themselves as rebelling against the staid conventions of the previous generation, what Holbrook Jackson memorably phrased in 1913 as the ‘smashing up [of] the intellectual and moral furniture of their parents’, in reality, many drew from earlier radical ideas. The sexual mysticism that enticed Bella and Charles Pearce for example, originated in the radical teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an eighteenth-century Swedish seer, while Edinburgh birth control campaigner Jane Hume Clapperton drew from a long tradition of feminist freethought or secularism. Also, in contrast to any sense of generational rebellion, despite holding some fairly transgressive views, cordial relations with parents appear to have been maintained. After a conversation with her mother on the tricky subjects of sex and religion, Anna Geddes commented that ‘of course each respected the others opinion & there was no ill feeling.’

How and in what ways does the book encourage its readers to think differently about Victorian Scotland? The history of sex in modern Scotland remains a fairly new avenue of inquiry. It has developed rapidly over the last decade with the emergence of a succession of ground-breaking studies. As a leading practitioner, what insights do you have into the emergence of this field? How is it changing the way we do Scottish history?

The individuals featured in my book had a habit, like the inheritors of their sexual radical thought, the modernists, of casting the Victorians as prudish and hypocritical, to better throw their progressivism into sharp relief. Don’t believe them! The sex lives of the Victorians were as complex and multifaceted as ours are today, with many nineteenth-century Scots rejecting the bourgeois conservatism of the so-called ‘unco guid’ or religiously respectable. And while the socialist and feminist subjects of my book did this in very self-conscious and public ways, there are numerous instances of individuals rejecting respectability in their everyday lives. Madeleine Smith, the daughter of a Glasgow architect, clearly enjoyed sex with her lover Emile L’Angelier, a clerk from the Channel Islands, writing to him in 1856 of how she ‘burned with love’ and longed to ‘place my head on your breast, kiss and fondle you’ (she was later tried for his murder, in a trial which scandalised Europe). Similarly revealing are the 1811-12 trial papers of Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie, two Edinburgh schoolmistresses who sued Dame Helen Cumming Gordon for libel after being accused by a pupil of engaging in a sexual relationship. The court evidence contains accounts of the teachers sharing a bed, lying on top of one another, and making a noise akin to ‘putting one’s finger into the neck of a wet bottle’, indicating, not unsurprisingly, that some same-sex female relationships in Scotland fell outside the common Victorian understanding of asexual ‘romantic friendships’. Working-class communities and cultures also had a range of sexual beliefs and practices, distinct from those of the middle classes. In villages in northeast Scotland, for example, bridal pregnancy was endemic, with bed-sharing before marriage considered an age-old and perfectly appropriate form of fertility testing. Furthermore, Fraserburgh fisherwoman Christian Watt was far more concerned with the dangers of sexual harassment than conforming to a middle-class moral code, carrying her gutting knife with her to plunge ‘into anybody who attempted to molest’ her while on the road. She was similarly straight-talking on the hypocrisies of her local Kirk elders, threatening to wreck the session if they summoned her for having an illegitimate child, by publicly exposing the ‘Fraserburgh business man who had in the past been known to frequent bawdy houses in Aberdeen.’

The recent scholarship on the history of Scottish sexuality has done much to expose this disjuncture between individual experience and societal attitudes, between what individuals felt and thought in contrast to what they were told to feel and think. A new emphasis on the history of emotions, alongside our established expertise in oral history, will only enhance this understanding. As importantly though, new research on sexuality has expanded who and what is considered important in our narratives of the past, with homosexuality, marriage, sex work, domestic violence, birth control, infertility and abortion all now significant topics for study. This allows more people to see their life experiences represented in our accounts of the past, often those previously marginalised within traditional histories. It also provides a rich store of analyses, insights and inspiration for our feminist, queer and trans activists, doing vital work to secure a more just and equitable future for Scotland.

I wonder what she would think of E. Michael Jones’ thesis that “modernity is rationalised sexual misbehaviour.” It sounds like there are some test cases here.

I think Michael Jones’ thesis could well be expanded beyond its narrowly Freudian horizon to read that ‘modernity is rationalised transgression’.

Jones is a prolific Catholic writer who seeks to defend traditional Catholic teachings and values from modernism and the ‘degeneracy’ of those who seek to undermine them. IN the book that made his reputation, Degenerate Moderns, he proposes that there are ultimately only two alternatives: either we conform our desires to truth or we conform truth to our desires. He favours conforming our desires to truth, which latter is of course realised in traditional Catholic teachings and values. (Other truths are available.)

I think Jones is on to something. Modernity does indeed champion the ‘Dionysian’ over the ‘Apolonian’, desire over intellect, corporeality over morality, the claims of the body over the claims of the mind. This one of the epoch’s definitive marks.

However, I’m not convinced this is the bad thing he says it is. I’m even less convinced that there can be a ‘truth’ that transcends the contingency of our sentient existence and is not produced by that existence. In the ‘culture wars’ of which he writes, I tend to be in the Dionysian camp. I suspect Tanya might be too.

She notes above that leaving the Kirk was a key enabler of the work of the “sexual progressives”. Jones has written quite a bit on Scotland (in “Barren Metal”), but only an earlier period. When he comes to the post-Victorian era, he looks instead at Bloomsbury. Part of the background to this period in Scotland must be William Robertson Smith, who tried to “modernise” the theology of the Free Kirk.

Yeah, Barren Metal is Jones’ Catholic critique of capitalism as part of the West’s degeneracy. The book could be criticised for its antisemitism: one of its main theses is that, as the Middle Ages gave way to modernity, God began to matter less and less, and Jews moved in to fill the void. Although, Jones has insisted against such criticism (rather unconvincingly, in my view) that race is not a factor in the struggle between Jewry and the rest of humanity; that it’s a religious story, rather, in which God plays the leading role and the Catholic Church is the agent of God’s work on Earth.

Regarding the Kirk, I’d imagine that leaving its ‘truth’ would be a necessary prerequisite of pursuing transgressive behaviour in Victorian and Edwardian times, especially if you were a woman.

I’ve just found this passage in Jones’ The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit (his study of the Masonic-Jewish takeover of Western civilisation. Have you read it?):

“Jews are often on the vanguard when it comes to trashing Christian mores and human dignity, and creating dysfunction whether its [sic] undermining gender and marriage or peddling promiscuity, pornography or abortion. … Organized Jewry has sought to portray man as inhabiting a mechanistic universe devoid of inherent design and meaning. In this view, God is an impotent fool who neglects His creation, and Christianity is fogbound superstition. … Organized Jewry has used our idealism to deceive us with Socialism, Communism and Zionism. But to warn Jews of this deceit now constitutes ‘anti-Semitism.’ Surely, Jewish leaders who start wars are the real anti-Semites. They create anti-Semitism to keep ordinary Jews in line.”

Mel Gibson springs to mind.

And, of course, Smith was a transgressive too. After his three-year-long trial for heresy (over his method of biblical criticism), he lost his position as Professor of Hebrew at the Aberdeen Free Church College and went into exile at the University of Cambridge, where he rose to the position of University Librarian, Professor of Arabic, and a fellow of Christ’s College. He never left the Kirk, however, and in time his late 19th-century ‘heresy’ was vindicated and his transgressive hermeneutics became 20th-century orthodoxy.

“Barren Metal” begins with a concept of usury as interest on a loan, but he then broadens it so that it becomes a term for what Marx calls surplus value. Apparently Catholic social theory (derived from Encyclicals) endorses a modified version of the labour theory of value, in which the element of exploitation is derived from subsistence wages that are not enough to bring up a family on. There were Jews involved in usury, but also Scots (on whom he has quite a bit to say), Italians, Germans, etc. You learn quite a bit about the Medici, Fuggers, etc and the politicisation of government debt. I had long given up on the labour theory of value, but seeing it in the context of the necessity of families for an ongoing society gave it a meaning again for me.

I’m pretty clear that there’s a lot more to Jones than his views on Judaism. I have read many of his books, but not yet JRS in full. It was out of print for a while, but there is now a second edition which I’m about 200 pages into. Thus far, he has more to say in it about Julian the Apostate and the (Protestant) Hussites in Czechia than Jews as such. For the Hussites, he relies on Norman Cohn’s Pursuit of the Millenium (once a well thought of book in these parts).

As for Mel Gibson, his father was some kind of traditionalist Catholic in Australia. I think the Jewish revisionist David Cole was making a film about him.

Jones is a radical traditionalist Catholic and sedevacantist, who rejects the authority of the Vatican and all recent Popes and believes his interpretation of Catholicism should be the basis for society and government. There’s certainly more to him than his antisemitism. But like many radical Catholic traditionalists, Jones’ ideology is largely built around antisemitism, which is so virulent that it even freaked out VDARE.

Jones’ antisemitism revolves around what he calls ‘logos’. ‘Logos’ is a Greek word, meaning logic or ‘ground’. In Christian circles, it’s often used to refer to Jesus Christ, who is held to be the ontological ‘ground’ of the universe. Jones claims that Jewish people were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus, and are therefore diametrically opposed to logos itself. This opposition comprises the ‘revolutionary spirit’ that makes them the source of all of society’s ills. He claims that the historical persecution of Jews (up to and including the Holocaust) has been justified.

Jones blames Jewish people for the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, feminism, homosexuality, pornography, abortion, and literally everything he doesn’t like. Jones despises Martin Luther King but appreciates Malcolm X. He’s particularly adamant in his book, Libido dominandi, that feminism and sexual liberation are political tools used by Jews to further control society. He called the Civil Rights movement a ‘Jewish War on the South’ and cites the cultural Marxism conspiracy theory. He also dabbles in economic antisemitism: Barren Metal is a rambling dissertation about how Jews destroy just economy through usury and free trade. He refers to non-cisgender, non-straight people as ‘deviants’ and credits himself with making Poland less supportive of same-sex marriage. He’s also an AIDS denialist.

There’s not a lot to admire.

https://angrywhitemen.org/2019/09/29/logos-rising-an-antisemitic-self-styled-theologian-is-influencing-a-new-generation-of-reactionaries/

That is mostly but not entirely accurate. To return to the theme of sexuality, Jones has written (in Living Machines) on modernist architecture as oriented to the needs of “sexual nomads” rather than families. He goes into the background of this in biographies of Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier.

In his work on music (Dionysus Rising), another part of his aesthetic theory, he traces the emergence of chromatic rather than tonal music from Wagner through to Schoenberg and then the rise of Rock ‘n’ Roll, which he sees as a combination of sexual rhythm and a return to tonality, after atonal music had emptied the classical music venues.

I’m not aware of anyone else saying these kind of things, which clearly need to be said and are rooted in Christianity. I suspect young readers of Logos Rising will soon be turning up at Scottish universities looking for a philosophical education, the way readers of Zen and the Art of Motor Cycle Maintenance did in the 1970s.

Yes, but why does he say these things, Stephen? What is the genealogy of his aesthetic theories? In the service of whose power-interests does he deploy those theories? What are their justification? Where do they begin to break down?

If any young person turns up at a Scottish university, looking for a philosophical education, these are the sorts of questions she’ll be encouraged to ask and in the techniques of pursuing she’ll be trained. She’ll be corrupted by the ‘Jewish revolutionary spirit’ and turned into a ‘degenerate modern’, in other words.

The sexual hypocrisy of Kirk elders seems a familiar theme.

What seems missing in this discussion is that for every revolution, it can be easy for duplicitious individuals (sometimes groups) to present themselves as ‘progressive’, and exploit the ‘true believers’. One might expect a certain amount of disillusionment as a result. There are also long-term consequences that can be less easy to predict, such as the breakdown of extended families resulting in a greater number of basic mistakes by new parent, even if they avoid some of the mistakes of their own parents.

Not merely the past, but the future was considered, by science fiction writers who imagined new and often more equal social relations, like free-love advocate HG Wells.

Socialist reformers were perhaps faced with a problem in including too-revolutionary or sexual themes in their educational materials, for fear of being accused of corrupting the young. Perhaps that is a contributory factor to the rather boring nature of socialist fables I’ve read in Michael Rosen’s Workers’ Tales. Nowadays, depictions of independent women may still be banned in educational material in religious fundamentalist jurisdictions.

However, the article says “Sexual desire is unruly and inchoate”. I would suggest that in the British Empire, sexual desire was often regimented and channelled in the single-sex boarding schools and military and church organizations that formed the generations of imperial administrators, aggressors and missionaries. And, of course, every day we seem to learn about some new atrocity, like the indigenous children who suffered all kinds of hideous harms in British Canadian ‘indian’ schools, penned and raped by their authority figures. You could call that misrule, but not unruly.

Of course, in his History of Sexuality, Foucault calls into doubt the received wisdom that Western society has experienced a repression of sexuality since the seventeenth century and documents the proliferation and diversity of discourses on sexuality in the fields of medicine, psychiatry, pedagogy, criminal justice and social work in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He concludes that sex became increasingly an object of social administration and management rather than repression. The transgressives of whom Tania writes were perhaps seeking to elude the ordering of their sexuality that prevailed at the time rather than its repression.