The German Greens can win – but can they end business-as-usual climate politics?

Ben Wray looks ahead to the German election next month, where the German Greens are in with a shout of being the largest party, or at least being a coalition partner in government. But can the party’s embrace of a moderate strategy actually deliver the climate leadership that Europe desperately needs?

“Code Red for humanity”. As fires engulf Greece and Sicily sizzles in 48°C record heat, just weeks after floods swamped Germany and Belgium, the latest IPCC report lays out in stark scientific terms what is evident in front of our eyes: the world, Europe included, is already deeply mired in climate breakdown.

If European governments treated the carbon budget – the amount of carbon we can still release into the atmosphere before temperatures will rise beyond 1.5°C – as seriously as their fiscal budget rules, we’d be phasing out European greenhouse gas emissions completely within a few years.

As Greta Thunberg pointed out following the IPCC report’s publication, “the carbon budget that gives us the best odds of staying below 1.5°C runs out in less than five and a half years at our current emissions rate. Maybe someone should ask the people in power how they plan to “solve” that?”

The sad truth is the “people in power” have already failed monumentally – they’ve known about the risks for decades and have not responded accordingly. Business-as-usual politics has put humanity in a situation where we are no longer in a struggle to stop climate change – that ship has sailed. We are now on a scale of climate breakdown, ranging from bad to catastrophic. Our fight now is to prevent bad from becoming catastrophic.

If we accept that the politics which dug us into this hole isn’t fit to get us out of it, what are the alternatives? In September, Germans will go to the polls for a Federal Election, with the the German Greens having an outside chance of becoming the largest party in the Bundestag for the first time, and a very strong chance of being a coalition partner in any future government. They are currently polling in second place, about eight-points behind the centre-right CDU/CSU.

Can the German Greens end business-as-usual politics and lead the charge against climate catastrophe in Europe’s largest economy?

A moderate response to a climate disaster

With climate crisis dominating the news in Germany, one would think this would be the perfect chance for the Greens to build momentum ahead of the 26 September poll, but it has not really happened. Polls have inched in their favour but they have not got back to the support they had in April and May, when the party was as much as seven points ahead of CDU/CSU.

To the frustration of many grassroots activists, the party leadership opted to respond to the floods with the hand brake on, cautious in drawing links between the extreme weather and the climate emergency. In an interview about the floods, co-leader Annalena Baerbock rated climate action third in priority responses, after improving disaster management systems and the design of German cities and waterways to cope with future flooding.

This response is part of a carefully crafted strategy to appeal to small-c conservative voters wary of talk of radical change. A key party election slogan has been: “economy and climate without crisis”. Party co-leaders Baerbock and Robert Habeck have been clear that they want to attract moderate voters disaffected with the two traditional establishment parties – and current coalition government partners – CDU/CSU on the centre-right and SPD on the centre-left.

“We can stabilise the political centre,” Habeck has argued.

The Brookings Institute, a centrist Washington think-tank, agrees, arguing in a detailed report on the German Greens called ‘Germany’s New Centrists?’ that the party can serve as “as a case study for Western democracies that are struggling to stabilise the political centre”.

The report finds that the Greens appear as a more relevant and less compromised force than the SPD, a party with roots in the labour movement’s of the early 20th century but which, like many of the old parties of social democracy across Europe, has “fading dynamism”, a decline which is “hollowing the political centre”.

The Greens, on the other hand, has “emerged as an appealing moderate force, having evolved from its radical, leftist origins“, it has “seized ground from the centre left by championing progressive, yet capitalism-friendly, policies” and “developed a constructive style that relies on the creation of wide-ranging coalitions and hopeful messaging”.

The leadership’s attitude towards corporate elites is indicative of the shift.

“Now, party leaders approach business as a partner rather than an enemy in the climate fight,” the Brookings Institute find. “Habeck attended the World Economic Forum at Davos this year, while business executives have joined the party’s conferences.”

To grasp how the German Greens became a centrist salvation, we need to understand the party’s evolution.

‘Realos’ defeat the ‘Fundis’

The West German Greens were founded in 1980 with a programme that was “guided by four principles: it is ecological, social, grassroots and non-violent”. They called for the “dissolution of military blocs, especially NATO and the Warsaw Pact”. The party was unusual at that time in being concerned with a broad range of issues, whereas most European green parties in the 1980s were solely focused on ecology. Growing out of Germany’s huge anti-nuclear movement at the time, the party achieved early success, winning 28 seats and 5.6% of the vote in the 1983 federal elections.

It was after this electoral breakthrough that a divide began to emerge between the ‘realos’, who wanted to work in coalition with other parties in parliament to push through reforms, and the ‘fundis’, who were more orientated on grassroots activity than parliament and wanted to transform the system. That divide continues to this day, although the realos are now unquestionably the dominant force.

The decisive victory for the realos came when the party entered government as the coalition partner of the SPD from 1998-2005. During this period in office, the Greens broke with a pre-election“peace policy” pledge and the party’s long-standing opposition to Nato, backing Nato’s military intervention in Kosovo, Germany’s first involvement in a war since WWII.

The party held an emergency conference where vice-chancellor and foreign minister Joschka Fischer told members that they are “no longer a protest party”. Fischer’s side narrowly won the vote on supporting the Nato bombing in Kosovo, and about a third of the party left in disgust. The party then went on to back Germany’s military operation in Afghanistan in 2001 as part of Nato, with their votes decisive in securing a majority for war in the Bundestag. Fischer had threatened to resign from the Greens if the party opposed.

During this period in office, the party also backed Schröder’s ‘Agenda 2010’ neoliberal reforms, which sought to suppress wage rises to make the German economy more internationally “competitive”. All of this increased the tensions between the party leadership and its base, and they lost four seats at the 2005 elections.

Since 2013, the party has been willing to form coalitions with either the centre-left or centre-right at regional level, now playing a coalition role in 14 of Germany’s 16 state parliaments. In Baden-Württemberg, the Greens have had the presidency since 2011, governing in coalitions with both the SPD (2011-2016) and the CDU (2016-present). Green President in Baden-Württemberg, Winfried Kretschmann, wrote a book in 2018 on what it means to be a conservative.

The party’s moderation has frustrated a younger generation of climate justice campaigners, some of whom have even set up a rival party, ‘Klimaliste’, which is made up of Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion activists and is organised on a grassroots basis. Klimaliste stood in Baden-Württemberg in the regional elections in March, claiming that despite 10 years of Green leadership in the region it had fallen behind some CDU-led states in terms of climate action.

“The Greens in Baden-Württemberg have lost a lot of credibility,” Alexander Grevel, one of the founders of Klimaliste, has said. “They are not a Green party anymore. They are just the CDU with some green paint on them, in my opinion.”

The party and the social movement

Germany has one of the strongest climate justice movement’s in Europe. The Fridays for Future demonstration in Berlin on the day of the global climate strike in 2019 was the largest on the continent. Germany has also seen a vibrant Extinction Rebellion movement and some of the most impressive mass civil disobedience actions anywhere through ‘Ende Gelände’. How does this movement relate to the Greens?

Michael Neuber, researcher in social movement studies at the Center for Technology and Society at the Technical University of Berlin, has been researching the climate movement in Germany since 2019, and tells Bella that it has achieved major political successes already, including pressuring parties, the Greens included, to strengthen their climate policies. But do they feel a party affiliation?

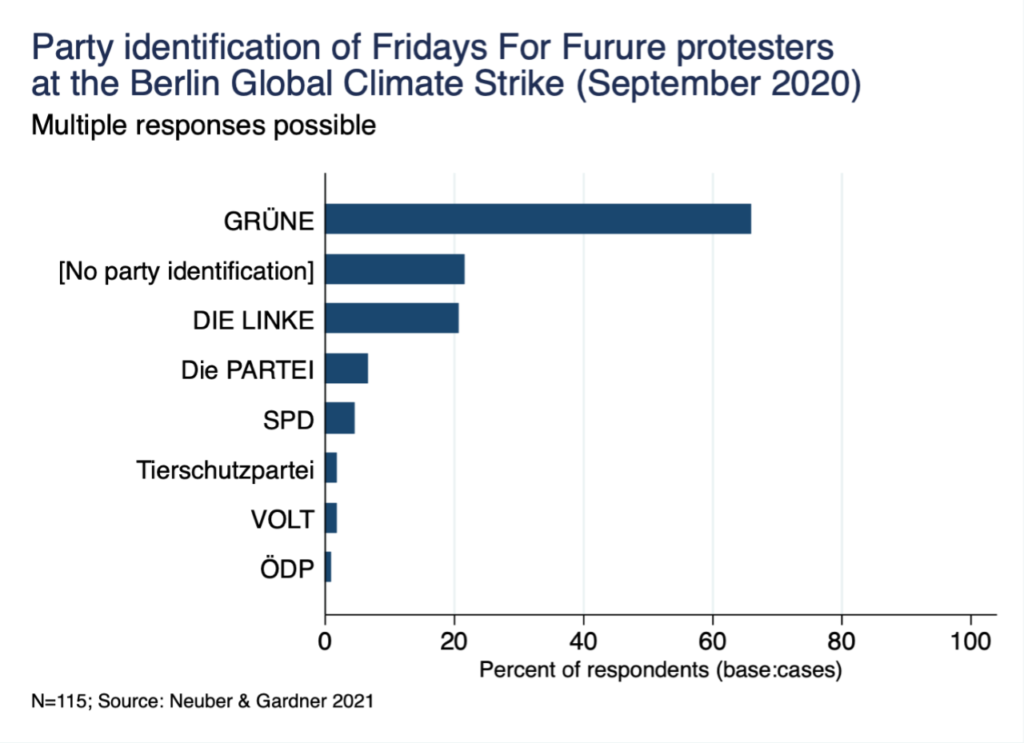

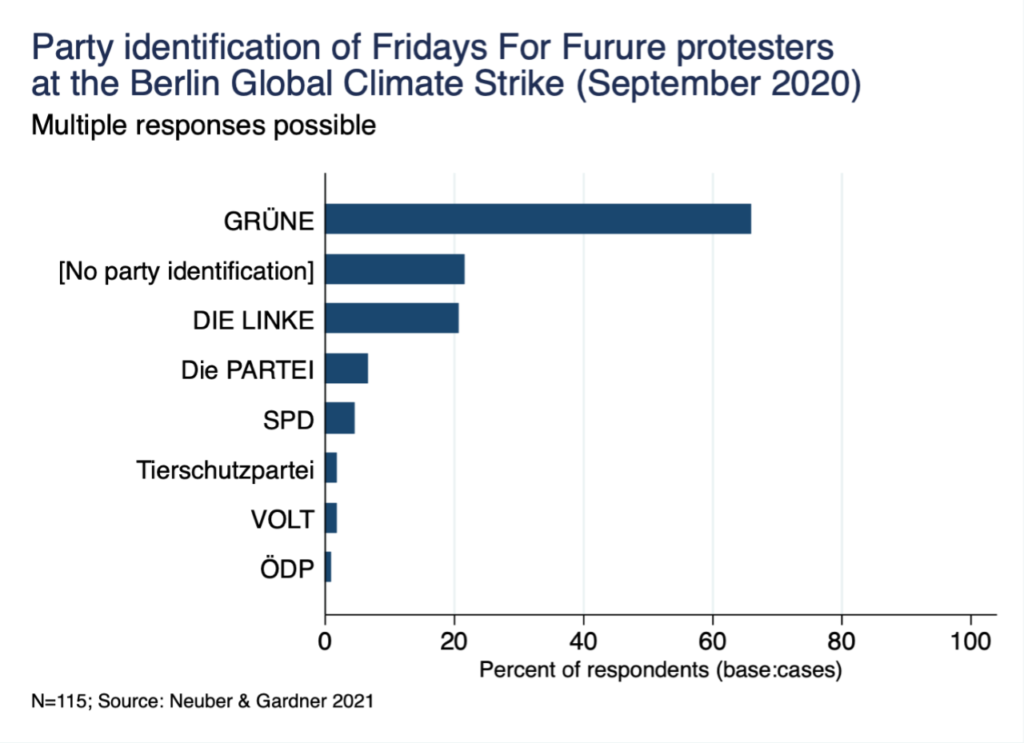

Research by Neuber and his colleagues suggests a fluid association between the social movement and parties. A survey taken at the 2019 global climate strike in Berlin (see graph above) found a strong identification with the Greens (‘Grüne’), with the Left Party (‘Die Linke’) the second most identified with. In terms of party membership, just 9 per cent of respondents were members, with about a third of those in the Greens and a third in SPD. A 2021 online survey of climate activists (not necessarily representative) found 20 per cent were party members, with most (23%) being a member of Klimaliste, with Greens and SPD joint second on 15%.

“There is a general skepticism towards the established parties, as climate activists feel that the climate issue is not treated seriously enough by those political actors,” Neuber finds. “That includes the Greens.”

Neuber says that rather than conceptualising the relationship between movement and party on a left-right or radical-moderate basis, it’s better to think about the movement in terms of a generational shift in values and expectations, akin to that which energised the 1968 youth revolt.

“The difference would be that people are rebelling against the business-as-usual of the establishment of the fossil fuel society, which also the Greens are considered to be part of.”

In this context, the Greens are “seriously concerned about losing the next generation of voters” , and therefore have been highly responsive to the demands of the social movement until now, but that may not continue if they do enter federal government after the election and need to strike compromises.

“The movement will monitor and evaluate the political decisions of such a green government very critically,” Neuber explains. “In particular, it will certainly keep an eye on the implementation of their promises made in the 2021 campaign. So that could be difficult for the Greens. I don’t think the protests would end in this scenario, in fact I think they would intensify.”

An effective strategy, or deadly compromises?

While the Greens may have reason to worry about a disconnection from the social movement, the party can point to a growing membership and electoral successes to justify the direction taken by Baerbock and Habeck, two members of the ‘realo’ wing, since they won the leadership in 2018.

The ‘green wave’ at the 2019 European Parliament elections saw the party finish second on 20.5% of the vote, well ahead of the SPD on 15.8%. The party ranks have swollen since then to over 100,000, becoming the fourth largest party in Germany. Between the 2017 federal elections and the 2019 European Parliament election, the Greens won 1.25 million votes from the SPD and 1.1 million from the CDU. The moderate strategy is clearly winning support away from the old German political establishment.

Secondly, the party’s willingness to work with parties across the political spectrum means it is well placed to enter government again following the federal elections, with the most likely outcome, according to the polls, being a CDU/CSU and Green coalition. The Greens have a wealth of experience in how to pursue their agenda in situations which require political compromise.

The problem with the politics of deal-making and consensus is that climate breakdown will not be compromised with: either the carbon emissions are reduced at rapid speed, or politicians professing their commitment to tackling the problem will clearly have failed. Will the Greens get their hands on power at the most important moment in the fight to stop climate catastrophe and fail to make full use of it?

The party’s manifesto has been criticised by activists for its moderation on climate action. The Greens target a 70% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, while the Left Party’s manifesto advocates an 80% reduction. The Greens support a carbon tax of €60 per tonne, which former Fridays for Future spokesperson and Green candidate Jakob Blasel has described as “toothless”. Klimaliste argue for a carbon tax of €195 per tonne. The Greens are “committed” to end coal extraction, the dirtiest of all fossil fuels, by 2030, and “want” to phase-out petrol cars by 2030 – such flexible wording may give the party room to manoeuvre, but it is not an expression of confident climate leadership.

There are definite positives to the Greens manifesto, such as a commitment to reform German and EU fiscal rules to allow for €50 billion per annum in green state investment, which would also be backed by a wealth tax on assets of €2 million or more and a digital corporation tax on big tech. The Greens have clearly learned from the Gilet Juanes revolt in France against Macron’s attempt to load the costs of carbon emissions reduction onto the working class.

“The lesson from France is that we cannot save the climate at the expense of social justice,” Baerbock has said. “The two things need to go hand in hand.”

However, the fear is that not only is the Greens’ policy-package insufficient to meet the scale of the challenge, but that in a coalition with CDU/CSU – the governing party in Germany since 2005 under the leadership of Chancellor Angela Merkel, who recently admitted that her governments have failed on climate action – those policies will inevitably be watered down further.

The CDU/CSU only plans to cut carbon emissions by 55% by 2030, and to phase out coal by 2038. Compromise in these core areas would be a betrayal of voters demanding climate action now, but the Brookings Institute’s research suggests that may be what the leadership is prepared to do.

“Several interviewees with insights into the leadership’s thinking acknowledged the Greens were seeking to preserve their flexibility now to limit internal discord but would establish clearer positions once in government,” the report states.

The worst possible scenario would be the party providing green cover for five more years of CDU/CSU climate delay at the moment when the whole of Europe will be looking to Germany for an end to business-as-usual.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by donating today.

No, they are also politicians. Putting Climate Change into the hands of politicians is suicidal. Wake up, if the people would lead then the leaders will follow…

The ‘fundi’/’realo’ dichotomy is just that, but a false one, so beloved of opponents of any political movement who seek to ‘divide and rule’ and thereby weaken the movement as a whole, and rendering it unable to access the ‘levers of power’.

The problem I have always experienced with ‘fundamentalists’ whether it is on the local bowling club committee, in a trade union branch, of the City Council, etc. is that things can only be done their way and the opinions of others are, by definition, ‘wrong’ – usually ‘totally, fundamentally and basically wrong’.

Politics is well described as ‘the art of the possible’, and that almost always requires compromise and deal-making. And, despite my belief in the real dangers inherent in climate change, there are still huge swathes of the population, whose day-to-day existence depends on how things are now, despite the fact that many accept and acknowledge that climate action is required. So, we have to start from where we are, not where we would like to be.

The Civil Rights movement in the US, under Martin Luther King and others recognised that but had their chant, “Keep your Eyes on the Prize”. This was not relevant only in the face of beatings and murders, but also inherent in accepting the legislation put forward by President Lyndon Johnson. Johnson, it should be remembered, successfully enacted more or at least as much, civil rights and welfare rights legislation than any other President, including Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt. What Johnson, and Lincoln and Roosevelt were, were very shrewd political operators who could make deals and significant ones. Of course there were also fairly grubby and, indeed, fatal decisions they took: Lincoln’s Civil War, Johnson’s continuation of the Vietnam War. The evil that men do does indeed, often live after them, but, so, too, does the good that they do.

While I admire idealism, I value pragmatism that gets things done, here and now, and improves the lives of many in a significant and long-lasting way. So, I hope that The Greens do achieve power in the Germany and are enabled to and supported in shifting the direction with regard to climate. The intransigence of some in the ‘fundi’ camp, serves only to provide propaganda for the opponents in their divide and rule strategies. It is well-documented how many ‘fundamentalist’ groups – antinuclear groups, feminists, ethnic campaigners, etc have been infiltrated by agents of powerful opposition interests. Of course, the ‘fundamentalist’ are important because they continue to indicate what the prize is.

What I get from this is that gradual progress is better than achieving nothing, but when you are faced with imminent climate catastrophe, gradual progress is the illusion of progress, because it’s failing to live up to the scale of the challenge, a failure that future generations will struggle like hell to rectify. I can understand why political instincts towards pragmatism have been built up based on the experience of the local bowling committee, the union branch and the city council, but we face a fundamentally different challenge to what those pose, one that requires a much more radical outlook on how change happens.

But, if you are unable to convince enough people to make as big a change as you think is necessary, what do you do? This is where some on the left (and in other areas of politics) tend to become authoritarian. We see this currently, for example, in some ‘trans ‘ groups and their attempts to impose terminologies on others.

Climate change, undoubtedly, is an a hugely greater scale, and some of the changes which will have to take place (and I think they do need to take place) will impact significantly on the lives of many in the short and medium term, unless substantial support is provided to enable them to live in a reasonable way until the change is effected. This requires being in positions of power, because some of those currently in power are unlikely to give up their power and a proportion of their wealth, easily. If Greens can acquire some power via the ballot box, then they have to use those powers, insofar as they are allowed, to further the case to convince enough of the hesitant to go a bit further.

So, if you think change is desirable then doing it ‘gradually’ seems to me to be the way it has to be done.

Now ‘gradual’ is an imprecise term but, it does imply ‘change’ and that, in turn, implies a ‘rate of change’. That rate of change can be greater or lower, or, even, negative. An analogy can be made with ‘acceleration’ as defined in physics. And the rate of rate of change can be changed, too. Once in power, then actions can be taken which increase the gradualism.

Catastrophes, of course, force change on people, and, sometimes, these can result in beneficial change, but, usually entail an acceptance of dirgisme, because it is for the common good. And, common good, implies a degree of consent, and, it is the gaining of consent that is always contested.

In my view, to bring about change for the most people, owner has to be obtained. This is where I feel that ‘fund is’ always fail.