A New Makar for Scotland

Poetry becomes people. The phrase was coined by poet and editor, Duncan Glen, to encapsulate the life-work of Hamish Henderson. The words are appropriately playful and ambiguous, and more buoyant than Auden’s similarly gnomic claim that ‘poetry makes nothing happen.’

Poetry becomes people: it suits us, is befitting, felicitous; or maybe it shapes us, so that who we are as individuals, as a community, a nation, is informed by the poetry we absorb.

Is this true in the 21st century? Was it ever? I think it might be. I think that some of the poetry I’ve read has helped me to better understand, and become, myself; and I know that I’ll never forget a poem like Edwin Morgan’s ‘Open the Doors’, commissioned for the opening of the Holyrood Parliament and as fine an example of civic poetry as you’d hope to find. Its response to the question of what people might expect of the parliament served as both warning and raucous encouragement: ‘A nest of fearties is what they do not want.’

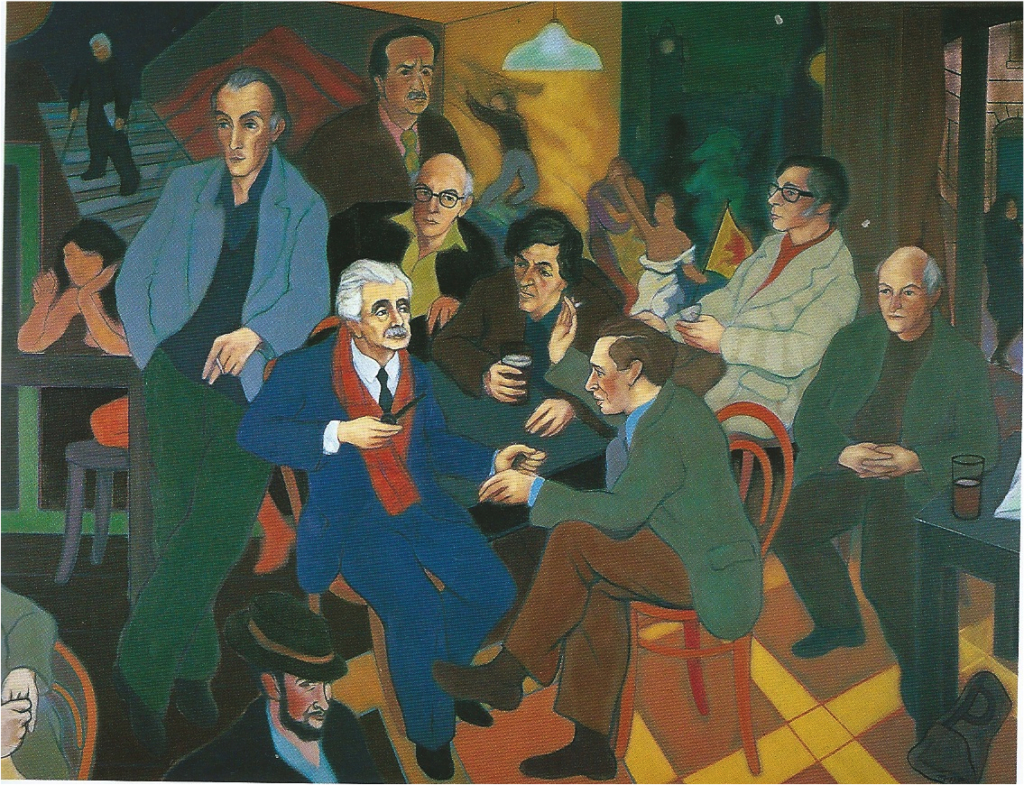

When Edwin Morgan was appointed Scotland’s first Makar in 2004, he was the last man standing of the Scottish poets immortalised in Sandy Moffat’s painting Poets’ Pub. Moffat probably didn’t intend his painting to circumscribe the canon of late-twentieth century Scottish poetry, but nonetheless, that picture of a group of all-white males is emblematic, with Hugh MacDiarmid at the centre, silver-haired and wearing a bold blue suit, an old man at the end of his life, but pack-leader still. The only woman prominent in the painting is anonymous and appears to be topless. She’s also being nudged aside by Norman MacCaig’s elbow. Such was poetry in Scotland in the 1970s. Though, of course, there was always plenty going on outwith the pub: Liz Lochhead and Tessa Ransford were establishing their voices, and there were others – poets like Janet Caird whose work has never received the attention it deserves.

The picture has changed. Forty years on, if Sandy Moffat was tasked to portray the pre-eminent poets writing in Scotland today, his painting would likely feature more women than men; and it’s no surprise that since Edwin Morgan’s death in 2010, it’s been two women that have held the post of Makar in turn.

The appointment of each previous Makar has made sense, not just because of the strength and breadth of their poetry, but also because who they are has added to our understanding of who we are: Edwin Morgan, only later in life able to publicly acknowledge his sexuality, a moment of liberation not only for himself but for many gay people in Scotland; Liz Lochhead, celebrating, but not confined by, the lived reality of urban, working-class women; Jackie Kay, bringing a sensibility shaped by the politics and peace-activism of her adoptive parents, as well as her own experience of growing up as a young black woman in Bishopbriggs. Poetry becomes people. People become poetry.

Our new Makar, Kathleen Jamie, is a worthy successor, having demonstrated both strength and breadth through half a dozen poetry collections, including The Tree House, winner of the 2004 Forward Prize, and The Bonniest Companie, which was the Saltire Society’s Scottish Book of the Year in 2016. The title, Makar, is also appropriate, given the use of Scots in her work. Jamie slips in and out of the vernacular in a way that seems unforced; that celebrates instead the advantages of access to more than one rich vocabulary, and that’s to do with the desire to deploy just the right word, irrespective of whether it’s in English or in Scots.

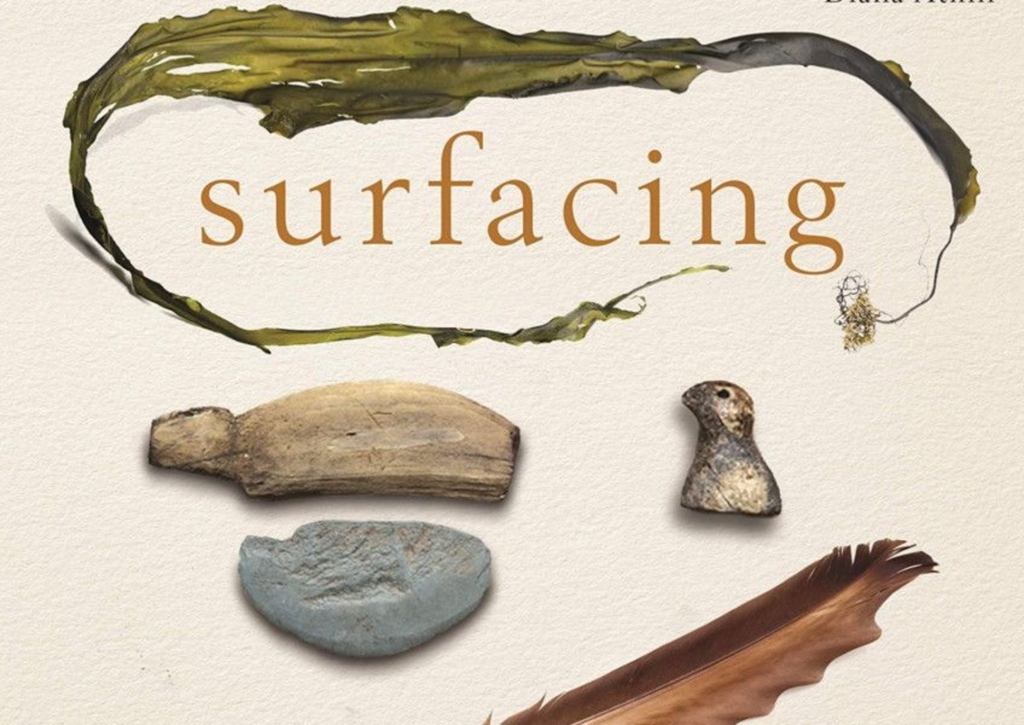

As well as her poetry, Jamie is the author of three books of essays that have been described by Richard Mabey as ‘as close as writing gets to a conversation with the natural world’. She herself likes the notion that her writing sits at the ‘confluence of nature, travel, and culture’; and in this, as well as in the tone of her essays, she reminds me of that other wonderful, inquisitive writer: the American, Barry Lopez. Whether it’s Jamie writing about an archaeological dig at a Yup’ik village in Alaska, in Surfacing, her most recent collection, or Lopez writing in Horizon, his last book, about the time he spent amongst the scattered artefacts of a palaeolithic people on Skraeling Island in the Canadian Arctic, both writers conjure place and people beautifully, generously. In her fascination for how places and things hold complex layers of meaning, and in the way that she excavates those layers, I think Jamie is the natural successor to Lopez, who sadly died last year.

Kathleen Jamie’s appointment as Makar is timely. Any poet or writer, or human being, attentive to what’s going on in Scotland these days, can’t ignore the reality of climate change and ecocide, the arrival of the Anthropocene. In her work, Jamie doesn’t shy away from that reality; instead, she seeks to explore and make room for it, to not be simply overwhelmed or to give in to despair. It seems a vital task for us all in these times: to look clearly and compassionately at where we are. As she says herself, in her editor’s introduction to Antlers of Water, a recent anthology of Scottish Nature and Environmental Writing:

For me, this noticing and caring, this attention, this writing from within personal circumstances, whether about an insect or a mountain, amounts to a political act. In a time of ecological crisis, I would argue that simply insisting on our right to pay heed to natural landscapes and other non-human lifeforms amounts to an act of resistance to the forces of destruction.

Noticing and caring, paying heed. This is Jamie’s craft, and it produces lean, honest poetry and prose that is a world apart from the kind of nature writing that relies on over-flowery evocations of rural life. Her world is anti-pastoral. In ‘The Gather’, from her collection The Overhaul, Jamie visits an uninhabited Hebridean island and cracks jokes with the shepherds who’ve crossed to the island to sheer the sheep that graze there, and to castrate the male lambs, throwing their removed testicles into a tub: ‘Oh, will they no’ mak a guid soup?’ And although she describes guillemots returning to their cliff-ledge nests, this is no island idyll. Disruption to the food chain means that the guillemot population is collapsing:

Aye, the birds –

not so many now…

and the men stood, considering.

Kathleen Jamie is a serious poet, though not sombre – there’s humour in her work, sometimes too dry to be easily noticed, but there nonetheless. More than anything, you sense a writer in love with the craft and graft of writing. In ‘The Woman in the Field’, published in Sightlines, her second essay collection, she remembers the thrill of starting out, of beginning to attend to ‘the weight and heft of a word, the play of sounds, the sense of carefully revealing something authentic’.

The next few years promise to be lively in Scotland. We’ve the aftermath of COP26, the SNP-Green deal for government, IndyRef2, the ongoing impact of climate change and Covid, the bourach of Brexit. What might we expect from our new Makar in response to all of that? And how will her voice add to our understanding of who we are?

There are some might be disappointed by the appointment. Much of the buzz around poetry these days is to do with performance, with poetry as a live art, where the delivery often sparkles more brightly than the content. When Amanda Gorman strode to the podium at Joe Biden’s presidential inauguration, she rightly caught the world’s attention: a young, black voice, proclaiming a kind of poetry that soared and inspired. But when you sit and read the poem on the page, without the passion of the delivery, it’s hard not to see it as overblown: aspirational poetry for a mythic America that has nothing to do with the lived reality of most of its citizens. No fear of that from Kathleen Jamie. Hers is a more tempered, grounded view, and nor is she a born performer. In an interview with Libby Brooks in the Guardian, published last Tuesday, she acknowledges that she’s ‘not naturally a public eye person.’ A kindred spirit, then, to Nicola Sturgeon, who you sense has had to work hard to embrace her public role. The two women seem to have much in common: their backgrounds and bookishness; their sharp, serious intelligence; their not-always-noticed wit. Maybe that bodes well, maybe the relationship between our new Makar and our First Minister will be a fruitful one.

When Kathleen Jamie’s appointment was formally announced, outside the Scottish Poetry Library in Edinburgh, she told reporters that her post ‘confirms a weel-kent truth: that poetry abides at the heart of Scottish culture, in all our languages, old and new.’ That affirmation, along with the body of work she has already created, suggests that she’ll be a fine Makar, one who might not grab the limelight, but who you’d trust with the necessary work of helping Scotland better become itself.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

It’s certainly true that poetry makes the people who read it (and vice versa). But who in Scotland reads poetry today?

Not enough.

Me.

“Poetry becomes people” – certainly both writing and reading poetry is an introspection that transforms, a process of becoming. I look forward to what we will learn about ourselves during Jamie’s tenure, both “helping Scotland better become itself” and hopefully become a better self too.

And let the lesson be — to be yersel’s,

Ye needna fash gin it’s to be ocht else.

To be yersel’s — and to mak’ that worth bein’,

Nae harder job to mortals has been gi’en.

Dougie, thank you for this. By a wee quirk of fate, I had just finished reading ‘Findings’ when I learned she was our new makar, having previously read ‘Sightlines’. I’d only seen a couple of her poems in Lesley Duncan’s ‘Herald’ column, so I immediately ordered a couple of volumes of her poetry, which arrived on Saturday. And which have been quietly filling my consciousness ever since.

So, to the rather challenged man above who asked the daft question, the answer is ‘more of us than you think’.

We now have a makar more than able to celebrate with us the strange and sometimes most uncomfortable world we have inherited, and some of us have helped make as it is. Mibbe I once thought that few would deserve the words ‘poetry becomes people’ as well as Hamish did. Your lovely celebration of her here, tells the world that our new makar most certainly does.

Kathleen Jamie is one remarkable woman. Congratulations to her for her well-deserved appointment. Your words are both accurate, and well-earned by her.

Dougie Harrison

Aye, I’ve known Kathleen for a while. She’s a very fine poet, and we share a passion for synthetic Scots as a literary language. I wrote in support of her a couple of years back when she almost gave up writing in Scots in despair at its organic ‘purists’.

I just find the hopes that you and the other Dougie pin on her as a poet a bit hyperbolic, given the small audience that poetry has in Scotland.

And here is that article from April 5th 2018:

Kathleen Jamie has revealed that she has given up writing the language she loves most: Scots. Disputes over the language, increasing political connotations of its use, and problems of legitimacy and readability have left her feeling that she can’t write it anymore.

Writing in the new edition of the ‘Irish Pages’ literary journal, she says that she has given up even trying to write Scots.

“But I want to. I long to, it’s the most intimate, heartfelt speech I have. It’s also wild and diverse and scunneratious and un-establishment. Some folk want to keep it that way, and not have become established and government-sanctioned and spelled correctly.”

She adds that, while some writers prefer Scots “unfixed, unteachable, like a sparrowhawk… [the] problems defeat me. I mean the problems of legitimacy, as much as readability.”

Kathleen is unashamedly a champion of ‘synthetic Scots’, which the purists deplore. She complains that, if she takes Scots words from people, books and dictionaries, “then it’s synthetic’, which is wrong, apparently.”

But, she points out, if synthetic Scots is judged to be illegitimate, then “we’re all reduced to the language we half-learned as a wean/bairn/child.”

She also notes that “a Scots which is just orthodox English with a few braw words displayed, as on a tee-shirt, that’s just signalling. Isn’t it?” (National Library of Scotland take note!)

While Kathleen finds it hard to find poets who write “real poems in good, fulsome Scots”, in her article entitled ‘The Wild Life of Scots’ she praises those of us who are “acutely interested in language, in syntax rather than messaging.”

She goes on:

“No one denies there is Scots speech… The politically motivated ding-dong about whether it’s a language or a dialect or just slang is very wearisome. If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck…

“And we haven’t even begun to talk about the independence referendum… Awful, if Scots is to be the mascot of one side only – guess which. I’m truly glad that I can’t make political assumptions about my neighbours based on their use of Scots.”

Let’s hope that, despite the harm that’s being done to the language by its purists and by political Scotsploitation and signalling, Kathleen can find it within herself to continue with ‘the most intimate, heartfelt speech’ that is poetry.

A thoughtful, insightful piece. And a kind one: not often you can honestly say that these days.

Thanks all for your comments. It’s always good to hear feedback and I’m glad the piece has, mostly, landed well with folk.