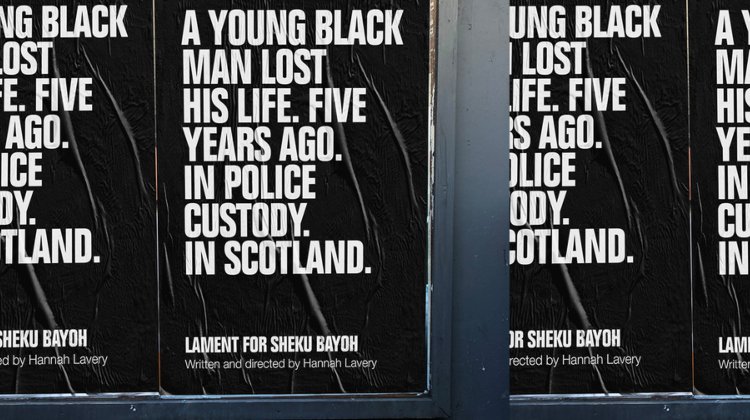

Lament for Sheku Bayoh: a timely reminder of the myth of Scottish exceptionalism

Shortly after the death of Sandra Bland in 2015, the hashtag #IfIDieInPoliceCustody began circulating prominently across Twitter. The result was numerous hard-hitting responses to the statement from activists, public figures and ordinary folk, which flooded the internet in defiance of the narrative that Bland had committed suicide in her jail cell. It was widely believed, as it still is, that Bland was the victim of police brutality and the outrage that followed was unsurprising, especially considering the nationwide tensions already in existence over the excessive deaths of Black Americans in police custody.

The #IfIDieInPoliceCustody hashtag was originated prior to Bland’s death by civil rights activist DeRay McKesson, who had used it in his response to the July 10 death of Alabama’s Anthony Ware. When the hashtag began doing the rounds again, it was impossible not to be taken in by the heaviness of everyone’s words. But at the time, it all felt very far away; as if we were onlookers in this horrific period of history. Because nothing ever happens in the left-wing progressive heart of Scotland, right? Wrong. Just a few months before Sandra Bland and Anthony Ware, 31 year-old Sheku Bayoh died after being forcibly restrained by up to six Police Scotland officers in Kirkcaldy. This was right on our doorstep, so how could we possibly feign ignorance?

It’s been six years since Sheku’s death and in the time since, it has become blindingly clear that there was an active attempt to smear his name; to absolve Police Scotland of any wrongdoing and ultimately pass the blame. While an inquiry – expected to last several years – is underway, no officer has ever been disciplined as a result of Sheku Bayoh’s death and no criminal charge has ever been brought.

In 2019, Hannah Lavery was working on an early version of what would eventually become Lament for Sheku Bayoh, arguably one of the most essential and striking pieces of theatre we’ve seen in Scotland in recent years. Originally commissioned by The Lyceum, the play ended up being performed at the 2019 Edinburgh International Festival as a work in progress, with audiences able to engage with it digitally. At the time, Lavery told Bella Caledonia: “I think that it’s important for us to talk about Scotland honestly, and to not turn our heads away from things that feel uncomfortable. I hope this play will be the beginning of a journey that will leave you with questions you want answered and give you an energy to pursue a better Scotland. For some of us it will be about being seen and heard, to have our knowledge of this country shared.”

Lament for Sheku Bayoh has been a game-changer in terms of bringing Sheku’s case back into public consciousness, harnessing the feelings of anger and hurt from the Black Lives Matter movement and the overwhelming desire to change, into something valuable. Despite watching the production on a screen with a dodgy internet connection, the emotion and power from everyone involved was conspicuous. It was evident that Lavery had created something so urgent that it needed to be seen by as many people as possible, in all walks of life, in Scotland and beyond. COVID may have temporarily halted its progress, but thankfully, Lament was announced as part of the International Festival’s 2021 programme, with a number of dates scheduled live at the Lyceum.

I knew that seeing the production in person would be a wholly different experience to seeing it on a screen but I was curious as to how its impact could be heighted, considering it had left such an impression when I initially watched the filmed version. In the socially distanced space, face to face with the exceptional cast – Saskia Ashdown, Patricia Panther and Courtney Stoddart – I wasn’t prepared for how Lavery’s words would reverberate so beautifully and so poignantly against the backdrop of scenes from Sheku’s life and Beldina Odenyo’s ethereal and devastating vocal/guitar soundtrack. Lavery describes Lament as a provocation in response to the general lack of awareness surrounding the Bayoh family’s campaign to get answers. It undeniably acts as a piece of education for anyone that may not be familiar with the case, but above all else, it forces us to confront that long-believed opinion that Scotland is free from racism and “not like those other places” we see on TV or read about on social media.

It’s fair to say that the events surrounding the death of George Floyd in 2020 and the resulting Black Lives Matter protests that took place globally ignited a spark in the fight against institutionalised racism and police brutality. In Scotland, there were protests held in multiple cities and crucially, this period was effective in bringing the attention back to Sheku’s case and to the fact that we are by no means the exception to the rule, but entirely complicit in the societal discrimation that empowers this type of violence against people of colour.

The regular looping of words and phrases in Lament and the jilted movements of the cast on stage emanate a sense of anxiety that is impossible not to feel in your chest. But you realise that the play succeeds in evoking such a visceral reaction because of the way in which Sheku is humanised by Lavery’s words. He’s not just facts and figures or newspaper headlines but a piece of Scotland; a representation of everything that modern Scotland strives to be. The snippets of dialogue about Scotland’s supposed lack of racism that occur amidst the main account are so familiar and depicted in a way that will resonate with any person of colour watching and listening. These are conversations that are commonplace, and for many, conversations that are exhausting, emotionally taxing but forever present.

Lament for Sheku Bayoh is at the Lyceum Theatre here.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by donating today.

‘…we are … entirely complicit in the societal discrimination that empowers this type of violence against people of colour.’

Yes, we do like to think of ourselves as exceptional and that we need only free ourselves from the dead hand of the English to let our supposed native genius for environmental and social justice flourish.

We just can’t accept that we’re complicit in our own moral turpitude. Hence we actively deny that complicity and alienate our culpability for our injustices onto that ‘other’ through the grudge and grievance of our alleged victimhood.

This is the social psychology of ‘ressentiment’. Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Scheler all viewed ressentiment as an influential force for the creation of identities, moral frameworks, and value systems. It’s the psychology that lies at the heart of all exclusion and discrimination.

It’s so tragic for the nation that many still define their ‘Scottishness’ in such a maladaptive and destructive way.

I recently watched the animated feature Batman: Year One, where incoming police lieutenant Gordon’s second-in-quick-succession encounter with Gotham police brutality comes when his new subordinate stops the car on the way to the station, gets out and beats a black youth unconscious without cause. Gordon chokes down his impulse to intervene, for reasons which are explored through the story. The movie is based on the Miller/Mazzucchelli graphic novel, which I’ve also read. You don’t have to swallow policing-by-billionaire-vigilante as a solution to be interested in the view of police corruption, the structures and practices which support it, and the difficulties faced by those wanting to change/improve the system from within. The gulf today between the corrupt police empire in fictional Gotham and day-to-day policing in Kirkcaldy may be great, but every time it looks like the police are acting with impunity, or providing deceitful testimony, or targeting certain demographics, you wonder which fictional police characters serving officers admire the most, and who they emulate in practice.

It’s not the workers you should be demonising, SD; the people we employ to police us are ordinary men and women, just like ourselves, who are constructed by the same prejudices as the rest of us. We’re collectively guilty; none is exceptional. As Arusa says: “…we are … entirely complicit in the societal discrimination that empowers this type of violence against people of colour.”

I agree with Arusa. As I said in my initial post, which is still awaiting moderation: “We just can’t accept that we’re complicit in our own moral turpitude. Hence we actively deny that complicity and alienate our culpability for our injustices onto that ‘other’ through the grudge and grievance of our alleged victimhood.”

This is just as true whether we’re demonising ‘immigrants’, people of colour, ‘the English’, or police officers.

I go in: “This is the social psychology of ‘ressentiment’. Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Scheler all viewed ressentiment as an influential force for the creation of identities, moral frameworks, and value systems. It’s the psychology that lies at the heart of all exclusion and discrimination.

“It’s so tragic for the nation that we still define our ‘Scottishness’ in such a maladaptive and destructive way.”