Make Bosses Pay

Make Bosses Pay (Pluto Books) is ambitious in scope, sophisticated in argument, and draws from thorough research, all of which Livingston makes lively and accessible through her sharp, lucid prose.

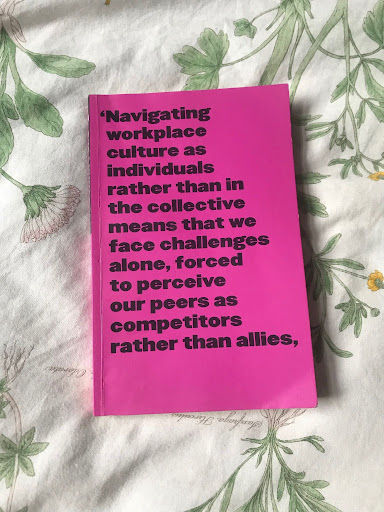

The book opens with a list of bad boss behaviour that will be uncomfortably familiar for much of the contemporary workforce: it tells a story of feeling powerless at a shitty job with no say over your hours, pay, conditions, or safety. It tells a story of workers living in poverty at the beck and call of their bosses, working through terrible life events and internalising the sense that at work, what you think, want, or need doesn’t matter.

Livingston describes the pervasiveness of these experiences as constituting “a feature of work”, though her book goes on to qualify this; it is a feature of work under capitalism that can be fought through the collectivity and solidarity offered by trade unions.

Throughout the text, Livingston simultaneously dispels the old myths about unions– that they provide protection as a service, that they are the purview of a particular kind of worker, that they are no longer relevant– while constructing a more radical and ambitious vision of unionising based on an analysis of the power dynamics in industrial relations and revealing the revolutionary potential of ordinary workers in solidarity with each other. She implicates the reader in the power and responsibility that this entails: “There is no abstract, unknowable ‘union’; no finite, locked box of power; no inevitable conclusion. There is only you, and me, and us, and what we choose to do.”

Livingston acknowledges that the former victories of unions so often touted to convince people to join them — eight hour days, the weekend — don’t resonate with a generation who regularly work weekends, random shifts on zero-hour contracts, or two jobs just to make ends meet. Still, she shows, clearly and succinctly, that we have never needed unions more.

Importantly, Livingston is not writing a defence of unions as they stand; she is aware of their limitations and does not shy away from the valid criticisms they receive, yet she insists: “Your union isn’t rubbish, it’s disempowered — and the only way to build back its power is by getting active.”

The book situates the contemporary challenges faced by workers and their unions in a historical analysis of the trade union movement in Britain. Livingston describes Thatcher-era attacks on unions compounded by post-recession anti-union legislation imposed by the Tory/ Lib Dem coalition. She tracks the shift from a unionised industrial workforce made up of mostly white men to a working class comprised largely of women and migrants in care and service jobs and thinks through what this shift means for trade unions.

She offers significant critique of the ways in which unions have yet to rise to the challenges of

the “gig economy” — or the proliferation of precarious work; the ways that union structures and cultures have reflected the white male breadwinner model of the worker; and how unions are yet to live up to the potential of ‘liberatory unionism’– in other words, taking social justice and solidarity seriously as whole worker trade union issues.

Make Bosses Pay highlights the importance of a trade union movement that centres deep, whole worker organising and takes seriously the organising and needs of the most precarious, rather than treating them as special interest issues separate from core class struggle. Livingston affirms:

“Our identities as women, as people of colour, as disabled people, migrants or members of the LGBTQ+ community are shaped by and shape how we experience our work and our class. They are foundations on which we can build and reinforce solidarity, not distractions through which it is eroded.”

From this she critiques the ways in which union structures have historically reproduced the structures of oppression that gave rise to them. She looks at the way that marginalised workers who have attempted to organise have often failed to find the solidarity they should have – from the Grunwick dispute to the organising efforts of sex workers– and argues that these issues are central to the liberation of workers.

Indeed, Livingston’s vision of trade unionism goes far beyond settling workplace disputes; it holds the potential for societal transformation and redressing the power imbalance between elites and the 99%. Unions, She argues, are capable of holding corporations and the rich to account and mitigating their political influence. Workers in solidarity with each other are more than the sum of their parts.

Besides drawing this powerful vision of trade unionism’s political potential, Livingston also addresses some of the practical steps unions can take to reach young workers. It is refreshing to see digital organising taken seriously. While some version of “posting isn’t activism” is akin to an ancient proverb for digital natives, Livingston shows that to reach young people, you have to go where they go, and often than means social media and digital tools. Particularly after a year and a half of adapting to organising in an online environment while reading about how organising must be done face-to-face with pen and paper, Livingston’s engagement with the potential of digital organising is a breath of fresh air.

Readers in Scotland will recognise many of the examples throughout the book: Better Than Zero, Living Rent, Unite Hospitality, and UCU, for example. Using contemporary case studies makes what Livingston is arguing for feel real, palpable, and achievable. Work doesn’t have to suck, housing doesn’t have to be exploitative, the powers around you can be redressed to work for the good of everyone. This book is a great step towards thinking about how to get there.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

As a white, heterosexual male who worked at a senior management level for most of my career, I agree that unions are needed more than ever.

I was a trade union member all of my working life. Unions can, indeed, be dysfunctional and can, indeed, come to represent the kinds of structures that they were established to challenge. The treatment of female employees over nearly 20 years by a clique of Labour councillors and trade union officers was disgraceful. the key issue is that people have to be active and engaged.

Often, the spur is a manifest grievance, but care must be taken to ensure that a ‘grievance culture’ does not come to dominate and become the raison d’etre for the union.

For most of us, our work is a substantial part of our identity and most of us like to do what we do well and, most importantly, to be creative about it and to make it better and more effective. it is also an important part of our social existence, given the large proportion of our waking hours which it takes up. Many colleagues are also friends and, indeed, have become spouses and partners.

So, join a union and be active in it, but don’t just fight injustice, fight for a better workplace where people feel they are part of something good and who have a degreee of influence over how it is run.

More women and othe groups once considered ‘minotities’ are in the workforce and the unions need to reflect their specific interests, too.

As is the case with any community, to be effective, unions need to be formed rather than joined.

Makes sense as a summary, although trade unions are almost by function necessarily somewhat reactionary, unless they can step outside the workplace. An analysis of bosses would also be useful, considering the growth of managerialist ideologies (boss-knows-best and deserves every penny of vastly inflated wage+bonus packet etc), and the possible infiltration of public service management by extreme right cadres (at the very least, this seems what they promised to do after all the ‘lefty teacher’ teeth-gnashing).

The better unions develop skills, although in my experience the large, generalist trade unions were not very interested in specialist concerns, and there are modern oppressions like corporations stealing employee’s off-duty intellectual property rights in even in irrelevant (or prior) areas through completely unjustifiable terms and conditions (which is in the opposite direction that bosses would like public focus to be on). This has apparently been increasingly the focus of lawsuits with the rise of pandemic homeworking, and touches on non-commercial activity like research, open source and digital commons contributions, as well as literature. I should hope that trade unions these days are better prepared to advise their members, especially since putting stuff online is what a lot of young people do every day, I guess.