Bold on Beyond the Swelkie

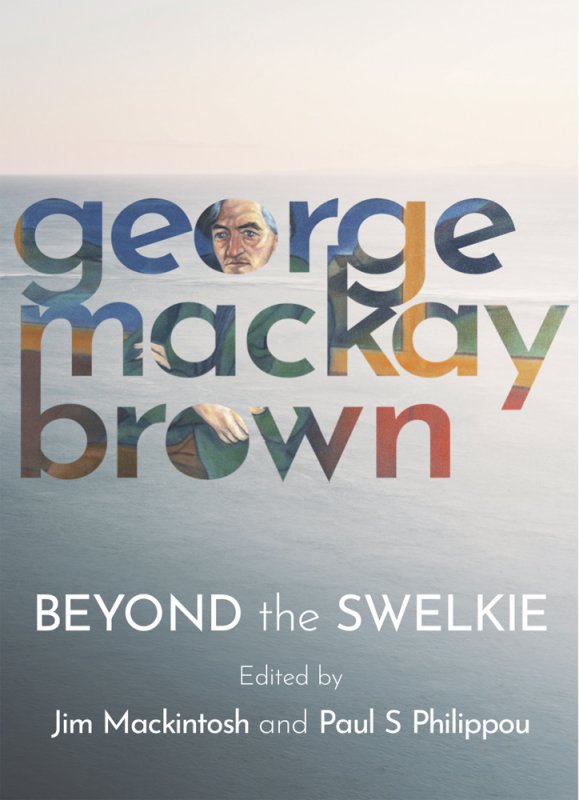

George Mackay Brown at 100. Jim Mackintosh and Paul S. Phillipou (eds), Beyond the Swelkie. A Collection of Poems and Writings Celebrating the Centenary of George Mackay Brown (1921 – 1996) Tippermuir Books. 260 pp., £12.

Stromness, 1975: hazy summer recollections of a slight man with a warm nature who connected easily with children, as I was then. We were staying in a borrowed house as my father revisited people and places from the last summer of his own childhood. My parents already knew George Mackay Brown, and I knew his legendary (in our family) comment, dismissing a city writer in a barb with a softened end: “biggest bloody bore in Edinburgh – nice man though”. Witty and, just as often, quiet.

I remember seeing George Mackay Brown walking around town and listening to the grown-ups talking as they sat, glasses in hand, in the pub. He seemed to be everywhere and to know everybody. Family was important to him – his own, and the wider community. My final memory is of the endless party at his brother’s house on our last night, sending us off for the early ferry next day. I recall kindness, humour and friendship: feelings more than events. This was a significant man who my father respected deeply and would, later, write about: George Mackay Brown, the Mackay separating him from George Douglas Brown. George.

Reading this wonderful new collection brought back a swell of memories for me, as it will for others. More importantly, its new perspectives open a door outwards, in George Mackay Brown’s centenary year. This is, simply, an important, book: a modern Orkney Tapestry. It loudly shows why George Mackay Brown will always be important: for his ain folk, and for others. It speaks volumes about how he continues to inspire new acts of creativity.

This is a hybrid volume — in a way that transcends the ubiquitous COVID word: bigger in content and ambition than an anthology; more of a self-contained world. It takes its title from a natural phenomenon, ‘the swirl and boil of the Pentland Firth and the maelstrom […] which makes any journey across it an adventure in both directions’ (Editor’s Note). It is laid out in two major sections: ‘Poetry and Short Prose’ and ‘Essays’. These are topped and tailed with a ‘Foreword’ by Asif Khan, which wears his erudition lightly, and a poetic ‘Postscript’ by Andrew Greig: ‘he willed / a craft so well made / he could sink on an even keen’ (p.234).

There are recurrent elements here. Several contributors, including Greig, are inspired by George Mackay Brown’s poetic final line: ‘I see hundreds of ships leaving harbour’. The statement is both epic – certainly with traces of Homer – and domestic. It reminds me of David Copperfield: ‘He’s going out with the tide […] People can’t die, along the coast,’ said Mr. Peggotty, ‘except when the tide’s pretty nigh out. They can’t be born, unless it’s pretty nigh […] And, it being low water, he went out with the tide’. This is a man who was part of the places that mattered to him, and who made them matter.

Beyond the Swelkie is haunted by good lines and key ideas: Brown’s ‘The shore was cold with mermaids and angels’ sparks off Marion McReady’s ‘Snow on the Shingle’: ‘They left ice-sparkles, blizzard-breath, they left / mementos, mid-winter souvenirs of their presence’ (p. 77). It also informs Louise Peterkin’s ‘Ambergris’: ‘Wastrel they say. Lazy. / But what the sea spews up, / the whale spewed up’ (p. 99). George Gunn’s timelessly beautiful ‘North of Troy’ is not alone here in approaching the writer as bard – in this case combining ideas from the Odyssey with the Prologue of the Edda: ‘the Sea has a certain rhythm / seek it / understand it’. In this context, ‘the sea is everything’ (pp. 37 – 42).

The pieces I like best engage most directly with Brown’s worldview. Christine de Luca’s ‘Licht Bringer’ (pp. 60 – 61) is enthralling: ‘Lö ta da callyshang: / a glisk at da past I da / soonds o da cadence’ [Listen to the hubbub: / a glimpse of the past / in the sounds of the cadence]. Soundscapes and silence; light and darkness; winter landscapes and storytelling – all of these are ever present here, as they were in George Mackay Brown’s work. As Ian Spring’s ‘Sonnet’ states, this book is ‘All for a soft silent boy, with sad eyes / reaping stories from stones and toil and salt soil’ (p. 113).

Contributors come from Orkney outwards: North to South; from Shetland to Scotland’s South West. These are outgoers and incomers and their responses to Brown are as diverse as themselves. James Robertson, in ‘A Fatal Blessing’ draws on Brown’s ambivalence to the concept of progress – ‘One sense a growing coldness – the coldness of people who have received the fatal blessing of prosperity (Brown, 1970)’ – to create an economical and resonant sermon to the present: ‘We are warm and safe, / and glad not to live in former times of aching labour, / superstition […] We have left all that behind’ (p. 106). Leela Soma’s ‘Madras Morning’ is ‘After Hamnavoe – a humble offering’, gentle and graceful as Brown’s own work. It seamlessly connects a landscape where ‘Orangey mustard streaks the lightening sky’ to Brown’s Orkney, through a call to ‘Quiet meditation, the start of a lovely dawn / broken, piece by piece as day breaks’ (p. 112).

Certain pieces stand out here – I have mentioned some, but not all, of these above. In the second section, it is the first-hand accounts of Orkney experiences that captivate the reader. Alexander Moffat’s ‘George Mackay Brown – A Portrait’ (pp. 195 – 203) powerfully tells the story of one of his best-known paintings and the ‘human interaction’ that led to its creation. Gerda Stevenson’s ‘Filming The Storm Watchers During Covid’ is a captivating account of new work made under the most difficult of circumstances, and the community of creativity that brought it into being.

The most moving, and engaging, of these personal essays is Ros Taylor’s, ‘My Uncle George’ (pp. 226 – 30). Her vivid writing about the ‘tall, gangly, curly-haired man with a large chin and smiling blue eyes’ reveals a great deal about Brown. It also suggests that a talent for storytelling runs through this family. Taylor reveals how Brown played with the truth in his anecdotes. There is his tale of being in his pram beside the baby Greer Garson, and how ‘he and Greer spent some time whacking each other over the head with their respective rattles, to their mothers’ horror […] the actress would have been 17 when George was an infant and […] had never lived in Orkney’. Then there is the story of the stone cottage which he named as ‘The Golden Slipper’: ‘no decent man would be seen going near the place’; ‘the story was embellished each time we passed the innocent cottage’.

In a book that gives more than its size would suggest, there are also critical essays from different angles. Linden Bicket returns to the theme of Brown’s Catholicism, which she treated in George Mackay Brown and the Scottish Catholic Imagination (2017). Erin Farley explores Brown as storyteller, in a piece on ‘The Everyday and the Eternal’ (pp. 145 – 51). Alison Miller’s ‘Notes of a Failed Nature Writer’ (pp. 188 – 94) shares her experiences as a returner to Orkney, somewhere which ‘pared itself down in my imagination to its elemental bones’ when she was away and, on her return, exemplified Brown’s statement; ‘Carve the runes, then be content with silence’.

It is not possible to list all the contents of this ambitious volume here. I urge you to read and enjoy it yourself. Suffice to say that it certainly, as it seeks to, highlights: ‘George Mackay Brown’s reach outwards from Orkney to draw people into his world and his looking inwards for inspiration – a cultural gravitational pull that worked in two directions’ (editors’ note). It took me back to a very special summer of stories – including my father’s of Dounby farm and an Orkney which embodied both loss and possibilities, resonating with the words of Rendall, of Muir, of Linklater, The Orkneyinga Saga and especially of George Mackay Brown. As Andrew Motion states, in ‘Writing’: ‘Whale roads and roofless crofts, / a tin bucket caught by the wind […] these entered his needle’s eye / and poured through into mine’ (p. 85).

Orkney lives imaginatively through the works of George Mackay Brown, along with those who went before him, those who are now here and those who will follow. One hundred years after his birth is a time for real celebration. This book achieves that, marvelously.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

Thank you for this Valentina. As an auld Scot interested in all aspects of our culture, and most aware that his islands are one of the few parts of our nation I have never even visited, I have only ever read – and been captivated by – a few of his poems.

This wee piece of yours has persuaded me to order the book. (And NO, certainly not from the dreadfully exploitative Amazon.)

Dougie

Coincidence! The first time we visited Stromness was in summer, 1975, too. As we stepped off the bus from the airport, George Mackay Brown was sitting on a bench waiting to board! We made a point of going to Rackwick on Hoy one day, having read about it in one of his short stories. There was a reading at the Arts Centre and George sat modestly in a corner, listening carefully, and it was obvious the reader was delighted to have such a figure in the audience. I think, over the years I have read most of his published works.

A few years later, when our daughter was about 5 we took her to Rackwick, too, and I have this wonderful photograph of her running along the edge of an otherwise deserted beach.