1981: The year Scotland re-wove its campaign to secure a Parliament

Forty years on, Douglas Robertson and Graeme Purves reflect back on 1981 and the various political and cultural developments which wove together the campaign that delivered Scotland’s Parliament.

The debating chamber of the Scottish Parliament Building © User:Colin / Wikimedia Commons /

The forces that had come together to campaign for a Yes vote in the 1979 Scottish Assembly referendum had made heavy political and emotional investments in a successful outcome. Their failure to achieve an Assembly (despite the narrow victory in the referendum vote) and the subsequent election of a UK Conservative government strongly opposed to devolving any power from Westminster were substantial blows. It was to take time for the various strands of the self-government movement to come to terms with what had just happened. Only then did they start to re-group, re-engage and re-organise.

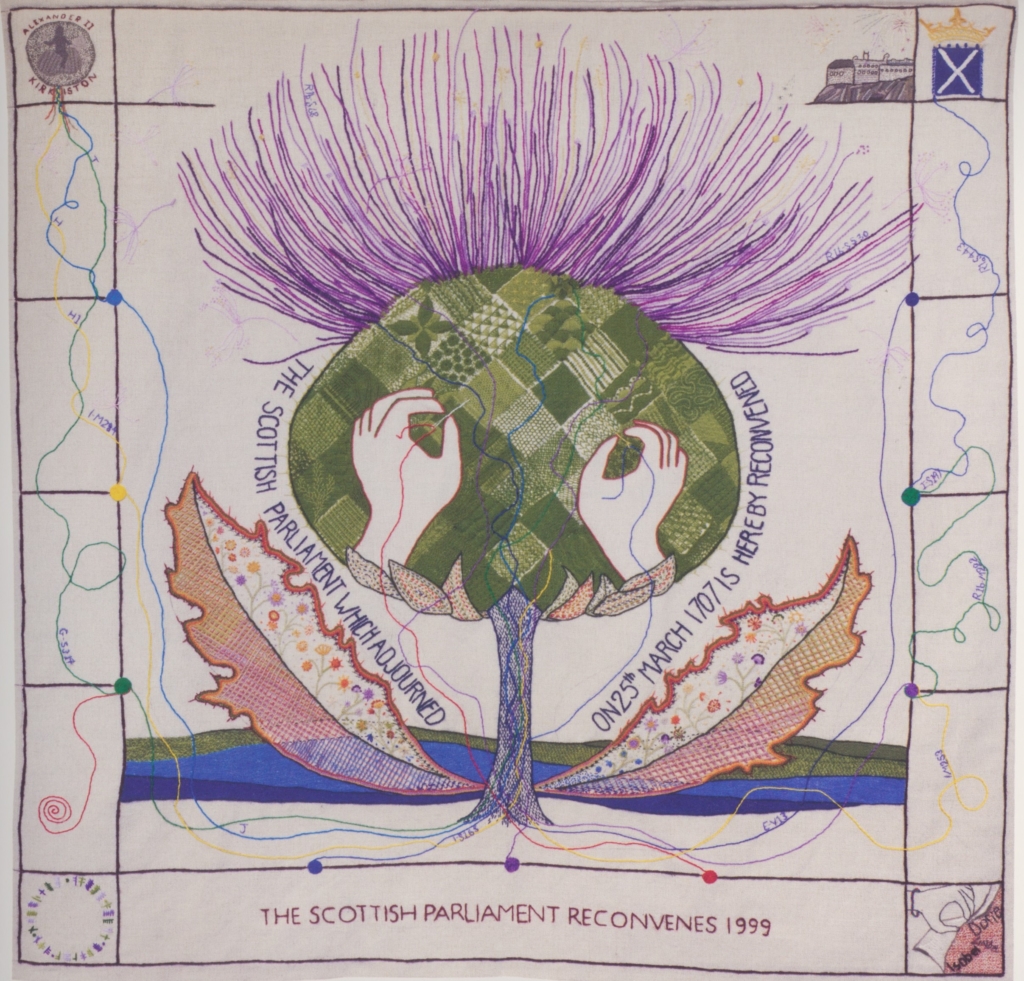

In 1981, there was still much uncertainty and little real leadership from senior figures in the political parties, but new ideas and debates about how best to move matters forward began percolating up from below. How these ideas and debates arose, how they were disseminated and then acted upon differed across Scotland’s established political camps. By examining various events in 1981 we can start to see how the fabric of Scottish politics and culture was changing. A national consensus started being woven together from the political campaigning warp and a contemporary cultural weft. It proved to be a rough, coarse and in places a spikey cloth, with many unfinished ends, but it was able to comfort, sustain and in time create a momentum sufficient to deliver a Parliament in just under 20 years.

Thistle Panel from the Great Tapestry of Scotland @ Great Tapestry of Scotland

The aftermath

While Labour had lost the 1979 UK general election, its share of the vote and number of MPs in Scotland had increased. It now held 44 of Scotland’s 71 parliamentary seats. Scottish voters continued to put their faith in Labour, but it quickly became apparent that the party was unable to protect them from the damaging impacts of Thatcher’s monetarist policies.

For the SNP, the 1979 election result was an outright disaster. The collapse in their vote all but extinguished that famous 1974 breakthrough. In the February election of that year, their 22% vote share secured seven seats, increasing to 11 on 30% of the vote at the October ballot. But in 1979 their vote share slumped to 17%, delivering only two seats, the Western Isles and Dundee East. Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan’s, famous jibe about the SNP being like: “turkeys voting for an early Christmas” proved painfully prophetic.

The Scottish Liberal Party, long stalwarts of Home Rule, retained the three seats they had held throughout the 1970s, on a slightly increased vote share, though it remained below 10%. Having propped up the Labour administration through a formal pact between 1977 and 1978, their leader David Steel was soon to pursue another political partnership, this time with what had been the right-wing of a fracturing Labour Party.

The political mood across Scotland was dark and fractious. Labour and the SNP blamed each other for Scotland’s predicament. In the eyes of the SNP, Labour had failed to deliver on devolution, being unable to marshal its own MPs. It had also been a Labour MP, George Cunningham, who introduced the mandatory ‘40% Rule’ which scuppered devolution, despite the majority Yes vote. But in Labour’s eyes, the SNP had brought down the Labour government, ushering in a radical Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher.

In the years immediately after the referendum most politicians and media commentators considered devolution ‘dead and buried.’ At the SNP conference in Dundee in September 1979, delegates ostentatiously turned their backs on devolution by electing ‘fundamentalist’ nationalists to senior positions. Gordon Wilson, the newly elected Chairman and one of their two remaining MPs, recognised this lack of balance in leadership roles to be problematic (1), as did a significant number of left-leaning, pro-devolution activists who then established the 79 Group. Margo MacDonald, a founding member, argued that devolution had proved to be a class vote, with the working-class supporting devolution while the middle-classes opposed it. Given this, said MacDonald, the SNP’s aim should be to build support among the working-class and directly target the Labour vote. Politically, for the 79 Group, the SNP’s future lay in becoming the radical alternative to Labour.

Campaigning warp

Meanwhile, activists from various political backgrounds started meeting to explore ways of keeping the self-government flame alive. This led to the launch of the all-party Campaign for a Scottish Assembly (CSA) at the headquarters of Edinburgh’s Trades Council in March 1980, exactly a year on from the referendum. Jack Brand, a political scientist, and an SNP and 79 Group member, was its first Chair. In an interview prompted by the event, Jimmy Milne, the communist General Secretary of the STUC, told The Scotsman’s Chris Baur that the Scotland Act had been “the creature of Westminster politicians who were only concerned with slinging together something that could get through parliament.” But how, asked Baur, could the implacably Unionist majority at Westminster be compelled to address fresh demands for devolution? “By making the mark II Bill a creature of a representative Scottish Convention,” Milne curtly replied. This was an early mention of a Constitutional Convention, an idea with a long pedigree, which had previously been deployed by the post-war National Covenant Movement. It was, in time, able to galvanise activists drawn from right across political and civic Scotland to set down a blueprint for the new devolved government of Scotland (2).

Prior to the 1979 referendum, the former Royal High School on Edinburgh’s Calton Hill had been converted to house Scotland’s proposed Assembly. In June 1980, in what was the first attempt to harness the symbolism of its empty debating chamber, the CSA staged its ‘Festival of the People’ immediately behind, on the Calton Hill. The event, the brainchild of Hugh Millar, took inspiration from the fêtes and fiestas which were part of the repertoire of the democratic socialist and communist parties of what was then termed Western Europe. It featured floats, music and drama, with the 7:84 Theatre Company performing a 30-minute excerpt from their then-current production, Joe’s Drum. The festival concluded with a ceilidh at the Zetland Halls in Pilrig Street (3).

The SNP leadership, now in full fundamentalist mode, had adopted the slogan “Independence, nothing less”, and denied the symbolism of a building associated with the failed Assembly project. Despite this, a significant number of SNP activists attended the festival. Conservative Ministers, on the other hand, were fully aware of the building’s potential as a totemic focus of opposition to their government, so sought ways to defuse its symbolism. One of these was holding meetings of the Scottish Grand Committee in the building, the first taking place in February 1982 (4).

In July 1980, George Foulkes, MP for Ayrshire South, announced the establishment of a Labour Campaign for a Scottish Assembly (LCSA), to build constituency support and exert influence at the party’s October Blackpool conference (5). That pressure worked, with the new party leader, Michael Foot, assuring a fringe meeting that he remained “fully committed to a Scottish Assembly.” (6) However, party opinions in Scotland remained divided. At Labour’s 1981 Scottish conference, held in Perth, more than a third of delegates voted against proposals to resurrect the commitment to a Scottish Assembly. Meanwhile, at an LCSA fringe meeting, stalwart Donald Dewar and emerging star George Galloway jointly moved a resolution stating: “the establishment of a Scottish Assembly will aid the advance towards a Socialist society” (7).

Some 500 people attended the CSA’s second convention in March 1981. However, it was far from being a mass movement, with only two active branches, one in Edinburgh, the other in Glasgow, and member groups in Aberdeen, Inverness, Perth and Fife. That said, those activists did embrace a wide political spectrum: the Labour Party, the SNP, the Scottish Liberal Party, the Scottish Ecology Party (forerunner of the Scottish Greens), the Communist Party of Great Britain, and the Scottish Republican Socialist Party, plus the Scottish Trade Union Congress and individual trade unions. Several prominent activists had previously been members of the short-lived Scottish Labour Party (8). This ensured the CSA had a wide political reach.

At the SNPs 1980 Rothesay conference, the 79 Group had tried to push the SNP leftwards, promoting a Margo MacDonald, Stephen Maxwell leadership ticket. After that failed, the Group set about building its organisation and stepping up internal campaigning prior to the 1981 conference to be held in Aberdeen the following May. It participated fully in a lively debate on party strategy at the party’s National Council held in Livingston on 7th March. A report by Gordon Wilson urged the SNP to bid for the ‘moderate niche’ in Scottish politics, but by the end of the meeting, he had to acknowledge that the party’s future lay as the radical alternative to the Labour Party. Later that month the 79 Group News was launched under the editorship of Chris Cunningham who, along with his sister Roseanna, was a founding Group member (9).

With what became known as ‘de-industrialisation’ gathering pace in Scotland, 79 Group and other SNP members became active in various local campaigns to save jobs. Showing solidarity with the trade union movement was breaking new ground for the SNP, though it had long fully participated in CND demonstrations. When, on 21st February 1981, SNP activists turned up to support the 50,000 strong STUC organised unemployment demonstration in Glasgow (10) there was some debate as to whether they should be allowed to take part. Eventually, the party’s Industrial Officer, Steve Butler, an ex-STUC official and 79 Group member, negotiated their participation, but only secured the slot at the very back of the march. In June, large numbers of SNP members joined a demonstration in Greenock in support of the Lee Jeans work-in, where women machinists fought to save their jobs. Later, activists occupied several Job Centres to highlight rising unemployment (11). Activists also joined demos outside the BMC truck works in Bathgate and the Talbot car plant at Linwood.

At the SNP’s annual conference that May, Jim Sillars, who had previously left the Labour Party to form the short-lived Scottish Labour Party, was elected Vice-Chairman for Policy, while Andrew Currie, another prominent 79 Group member, was elected Vice-Chairman for Organisation. Overall, delegates stuck with a predominantly fundamentalist leadership, but they sided with the 79 Group’s radical positioning. They voted by a large majority for a motion calling for “a real Scottish resistance”, including “political strikes and civil disobedience on a mass scale.” Gordon Wilson responded by putting Sillars in charge of the ‘Scottish Resistance’ campaign (12). At the subsequent National Council in Stirling, five 79 Group members were voted onto the party’s National Executive Committee (13).

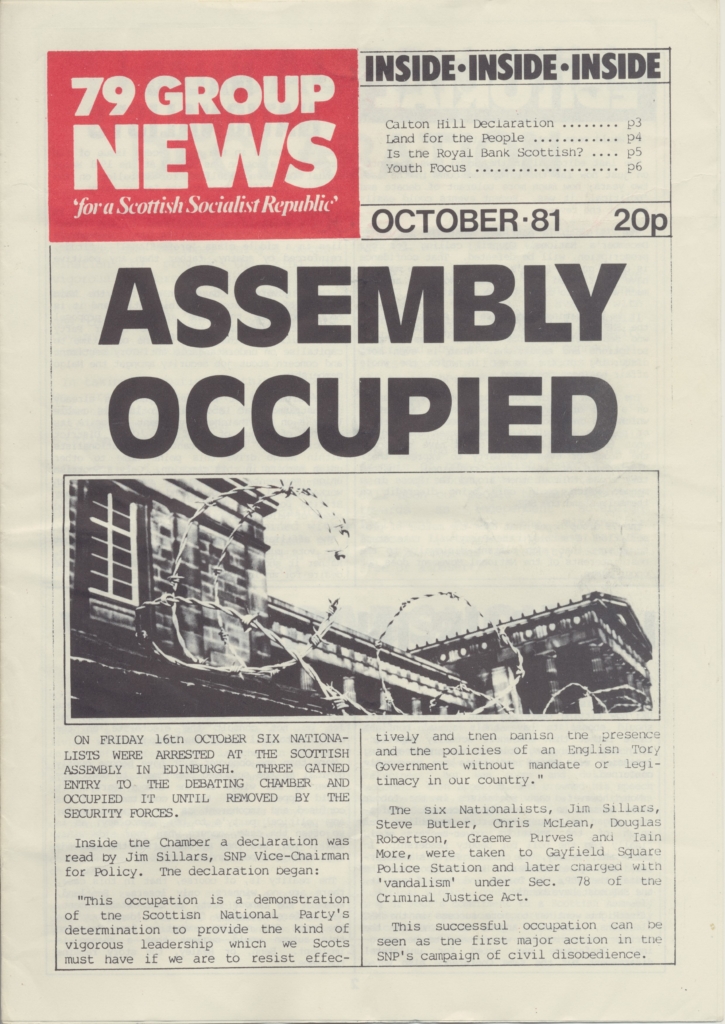

In September, 79 Group News warned of government plans to turn the empty Assembly building into a law court, arguing that it should become a focal point in any future campaign for Scottish democracy (14). A month later, on the 16 October 1981, Sillars and five other SNP members (Steve Butler, Chris McLean, Iain Moore, Graeme Purves and Douglas Robertson) broke into the Assembly building (15). All but Moore were 79 Group members. The protest sought to link the empty Assembly building with the accelerating rise in unemployment. Three of the six succeeded in gaining entry to the debating chamber where Sillars read a declaration stating, “This occupation is a demonstration of the Scottish National Party’s determination to provide the kind of vigorous leadership which we Scots must have if we are to resist effectively and then banish the presence of an English Tory Government without mandate or legitimacy in our country (16).”

79 Group News, October 1981 Credit: Authors

All six were soon arrested and held at Gayfield Police Station where, after consultation with the Solicitor General, Nicholas Fairbairn, they were charged with vandalism under the recently passed Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 1981. They had hacked out the wooden astragals of a roof window with an axe in order to access and drop down into the debating chamber.

A week later, on 24th October, around 1,800 SNP activists gathered on Calton Hill to highlight the absurdity of having an empty Assembly building when it should have been debating what actions were needed to tackle unemployment. Speeches focused on Scotland’s high levels of unemployment and the militaristic policies being pursued by the Tory government, namely the deployment of Cruise missiles and the Trident nuclear up-grade for Faslane on the Clyde. Three more party members – Jim Campbell, Ruth McQuillan and Charlotte Reid – were arrested after chaining themselves to the Assembly building railings (17).

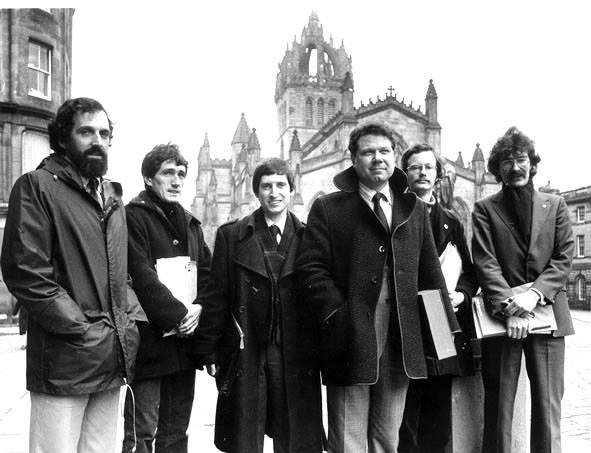

The subsequent trial of the SNP six was held at Edinburgh Sheriff Court in January 1982. The defence submission was that the Act under which they had been charged was inoperable, as it would not have become law had the Assembly Act not been illegally repealed (18), given that criminal justice matters would have been a devolved Assembly power. The case was tested in an appeal to the High Court and lost. The legal nuances of the judgement, which relied in part on the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway Company Act of 1826, ensured its failure to engage public interest (19). The vandalism convictions and fines thus stood.

Break-in accused outside Edinburgh Sheriff Court, January 1982, Credit: Authors

In the wake of the Assembly break-in, senior figures in the SNP decided that they had had more than enough of the ‘Scottish Resistance’ campaign and moved to rid the party of the 79 Group. At the party’s annual conference in Ayr in June 1982, delegates passed resolutions reaffirming a left-wing profile for the party, though bizarrely, also passed a resolution that rejected civil disobedience to protect jobs. However, all this was quickly overshadowed.

At a fringe meeting of leading traditionalists to launch their ‘Campaign for Nationalism in Scotland,’ Winnie Ewing declared the move was explicitly intended to provoke a confrontation with the 79 Group so that the party would be forced to move against it. Party Chairman Gordon Wilson happily obliged. The following day, he departed from his intended keynote address to announce that he would table an emergency motion to ban all organised political groups within the SNP (20). Most 79 Group members in the hall immediately walked out of the conference in protest. (21)(22)

In his memoir, Gordon Wilson likened these internal conflicts to deal with a plague of Jacobins (23). Stephen Maxwell viewed matters differently, describing what happened at Ayr as “a traditionalist counter-charge into the nearest ideological funk-hole (24).” With the demise of the 79 Group, the SNP again scurried down into their fundamentalist burrow, standing aloof from cross-party efforts to bring about a Scottish legislature, though many individual SNP members remained active in the CSA. The party’s preferred positioning delivered only limited electoral success over the subsequent fifteen years.

March 1981 had also witnessed the emergence of a new UK political force, the Social Democratic Party (SDP), when the so-called ‘Gang of Four’ (Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams) split from the Labour Party. In an article in the spring issue of the magazine Crann-Tara, Danus Skene, then a Scottish Liberal Party member and an independent councillor, argued that, despite the strongly centralist philosophy espoused by leading English social democrats like Anthony Crosland, the SDP should be given the benefit of the doubt on the question of Scottish self-government (25). In fact, the ‘Gang of Four’ had explicitly cited the devolution of power to Scotland and Wales as one of the reasons for their break with Labour. However, given that this stance quickly became a potential impediment to rapprochement with the Liberals, the SDP was obliged to back-pedal, explaining limply they were not opposed to decentralisation per se, only to Labour’s ‘lopsided’ policy. They undertook to come back with a ‘British wide regional government scheme’, but at the 1981 Liberal Conference in Galashiels, David Steel made it clear that Scotland could not wait for ‘Home Rule all round’, so should now act as a pacesetter for constitutional reform (26).

Traditionalists in the SNP believed that the party would do well to emulate the Social Democrats by staking a claim for the middle ground of Scottish politics, a view strengthened by Roy Jenkins’ Glasgow Hillhead by-election victory in March 1982. George Leslie, the affable SNP candidate secured only 11% of the vote. In July 1982, the Social Democrats delivered on their earlier constitutional promise, calling for 13 regional assemblies elected by proportional representation across the UK, as part of a wider package of reforms including the abolition of the House of Lords and the introduction of single-tier local government. Privately, Liberals dismissed the proposals as ‘utopian’ and they had faded into obscurity by the time of the merger of the two parties in 1987 (27). That said, over the last four decades such proposals have made convenient re-appearances, only to then quickly disappear again, and again.

Meanwhile, the frustrations caused by Scottish Labour’s perceived political impotence, despite its numeric strength in Scotland, was leading to unrest within its membership. Scottish Labour’s own ‘Gang of Four’, George Foulkes, John Maxton, David Marshall and John Hume Robertson did not relish the prospect of a protracted period in opposition. Later Denis Canavan and Dundee’s George Galloway and John McAllion expanded this self-styled awkward squad. In July 1982, the Sunday Standard, the new Scottish Sunday paper launched by the Lonrho Group the previous year, reported that as many as fourteen Labour MPs were moving towards support for independence (28).

Traditional party-political vehicles were finding it hard to challenge the new ideologically driven Conservative Party. Labour and the SNP fought each other, and amongst themselves via internal disputes. This created a great deal of tension, soul searching and political flux, given that no effective protection could be given to individuals and groups suffering from the brutal impacts of monetarism and rapid de-industrialisation. It was in this challenging political environment that new thinking began to emerge. New arguments were put forward by a range of different voices in spaces normally associated with the country’s cultural architecture. Arts and culture stepped up to develop modern narratives about Scotland which complemented and supported campaigning for self-government. And again, the beginnings of this are to be found in and around 1981.

Cultural weft

Cairns Craig, in his book The Wealth of the Nation: Scotland, Culture and Independence (29), argues that there was a direct cultural response to the dashed political hopes caused by the failed devolution referendum. Until that time, many Scottish commentators had espoused what he termed ‘nostophobia’, a pessimistic preoccupation with the cramping, provincial inadequacies of Scottish culture. This had become the dominant intellectual discourse in the immediate post-war period with figures as diverse as Edwin Muir, Allan Massie, Alexander Trocchi and the film-maker Bill Douglas each providing their own particular contributions to the construct.

Tom Nairn, in an article for Scottish International (30), the 1970s citadel for ‘nostophobia’, had argued that the Scots, liberated from the debilitating constraints of a failed national culture, were now well placed to provide the intellectual vanguard of a new post-nationalist world. It was therefore a rich irony that it was Scottish International’s conference, ‘What Kind of Scotland?’, held in Spring 1973, which witnessed the first performance of John McGrath’s The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil. The standing ovation given by an enthusiastic audience can be seen as marking the exhaustion of the ‘nostophobic’ impulse.

Craig uses the term ‘theoxenia’ to describe the cultural response to the political hopes dashed by the outcome of the 1979 devolution referendum. This was the adoption of a new perspective that was able to combine respect for Scotland’s various indigenous cultural resources, with ‘a receptiveness to the gifts of gods who come as strangers’ (31). He credits Edwin Morgan as being a critical figure in bringing about this change but also identifies Alasdair Gray, Liz Lochhead and Ian Hamilton Finlay as being leading contributors to this phase of cultural revival.

Scott Hames, in his recent book The Literary Politics of Devolution (32), picks up on this, noting the significance accorded to literature as a touchstone of cultural vitality in the period between the referendums of 1979 and 1997. Alasdair Gray’s Lanark, published in 1981, was probably the most iconic Scottish novel of this period. Some 30 years in gestation, it was hailed as evidence of the continuing vigour and distinctiveness of Scottish writing. In that Autumn’s issue of the arts and culture magazine Cencrastus, Cairns Craig saw it as marking “a new level of ambition and achievement” in a literature of working-class life which had been slowly emerging over the past twenty years (33). Anthony Burgess felt moved to describe Gray as “the best Scottish novelist since Walter Scott (34).”

That emergent working-class literary canon embraced both prose and poetry. In the writing of William McIlvanney, James Kelman, Ian Banks, A.L. Kennedy and Janice Galloway a distinctive Scots voice and identity was central, reflecting lived experience and contemporary culture. In poetry, an older generation of male poets such as George Mackay Brown, Tom Leonard, Edwin Morgan, Sorley MacLean, Alexander Scott, Alan Spence and Iain Crichton Smith had long embraced that locus. Liz Lochhead’s work helped prise open doors for a new generation of poets by offering female perspectives, breaching what for so long had been a largely male domain, as the Scottish Poetry Library’s ‘hall of fame’ amply illustrates. The work of Dilys Rose, Jackie Kay, Imtiaz Dharker and now Kathleen Jamie is emblematic of that shift.

In seeking explanations for the remarkable survival of Scotland as a distinct literary, cultural and class entity, the roles of music hall, pantomime as well as folk and popular music are too often ignored in the academic discourse. Where would the distinctive Scottish voice and insight be without figures like William D. Latto, Stanley Baxter, Jimmy Logan, Jack Milroy, Rikki Fulton, June Imrie, Una MacLean, Elaine C. Smith, Robbie Coltrane, Andy Gray, Gerard Kelly, Craig Ferguson, Gerry Rafferty, Hamish Henderson, John Byrne, David Hayman, Michael Marra, Sheena Wellington, Ishbel MacAskill, Jimmy Shand, The Corries and Karine Polwart? And no one can doubt the tectonic impact on Scottish identity, culture and class which Billy Connolly brought about. So why has the massive contribution made by truly popular culture never been fully acknowledged? This is an old chestnut, but we still, led by academia, for whatever reason, choose to embrace either a narrow literary or a very ‘Imperial’ British Arts Council understanding of ‘culture’ (35).

In his memoir recounting the long campaign for land reform, Reclaiming Our Land, Rob Gibson notes the important contribution made by songwriters and musicians in not only articulating a political resistance towards Thatcherism but also helping to drive the cultural revival during the 1980s, essentially Craig’s ‘theoxenia’ (36).

In terms of folk and popular music, this revival embraced both the Gàidhealtachd and Lowland experiences, both urban and rural, as well as drawing in and on the voices of traveller communities. This revival benefited greatly from the painstaking work of enthusiastic collectors such as John Lorne Campbell, Margaret Fay Shaw, Hamish Henderson, John Purcell and Norman Buchan (37).

This blending of cultures can be found in the music of Dick Gaughan, Ossian, Silly Wizard, Boys of the Lough, The Tannahill Weavers, Battlefield Band, Wolfstone and earlier pioneers such as Hamish Imlach, The Corries and Gaberlunzie. Added into that mix was the class dimension in the songwriting of the likes of Eric Bogle, and the polymaths Dominic Behan and Freddie Anderson. Anderson, a playwright, author, poet and communist was an influential figure in working-class culture and the folk music scene from the 1950s onwards.

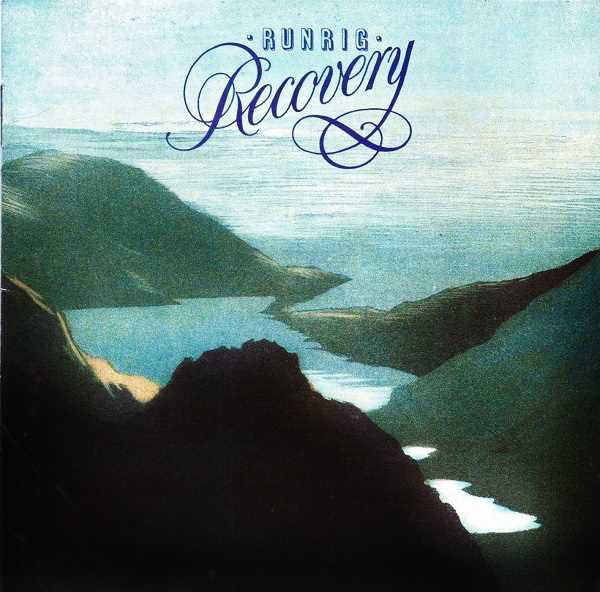

The Glasgow Folk Festival, established in 1980, was one of the events where the revival was played out. Alan Stivell (38) headlined in the 1981 Festival with his Symphonie Celtique, a blend of Breton nationalism and Celtic electronic revivalism. An early example of a Scottish Gaelic response to this was Runrig, whose third album Recovery was also released in 1981. It dealt with the social history of the Gàidhealtachd, reflecting a renewed sense of cultural confidence within the Scottish Gaelic community, and coinciding with the Gaelic road signs campaign which paint-bombed English-only road signs across the Gàidhealtachd. That musical revival was picked up and further developed by Capercaillie, founded by accordionist Donald Shaw and singer Karen Matheson, taking modern Gaelic music to a world stage on foundations laid by singers like Ishbel MacAskill and Dolina Maclennan. The major change, however, was that this new music revival was for dancing to, not just listening.

Runrig Recovery, 1981, @ Ridge Records

Across Scotland during the early 1980s, contemporary political and cultural themes were beginning to be addressed by popular bands such as Big Country, Deacon Blue and Aztec Camera, as well as singer-songwriters such as The Proclaimers, Dougie MacLean, Jim Malcolm and Malcolm Middleton, who harked back to the earlier folk traditions. Much later, Martyn Bennett, in his seminal LP Grit, tied up all these threads, while also blending in recordings captured years before by Hamish Henderson and others at the School of Scottish Studies.

That blending of the contemporary with past cultural traditions had been used to great effect by 7:84, founded by John McGrath and Elizabeth and David MacLennan back in 1971. Borderline Theatre Company and TAG had also honed their own blend of agitprop theatre, as had Wildcat, Communicado Theatre and Theatre Babel, all founded later in 1982. Earlier in March 1981, the Scottish Theatre Company, the brainchild of Ewan Hooper, had been launched at the MacRobert Theatre at Stirling University. It operated a policy of presenting both Scottish and international classic drama, while at the same time commissioning new works. It had a successful first season, toured nationally and staged productions for the Edinburgh International Festival (39). Yet despite attracting large audiences and successfully securing commercial sponsorship, including from Scottish Television, it had to be wound up in 1987 when the Scottish Arts Council ceased its annual funding, as was the case for Borderline, Wildcat and Communicado. It would take almost two decades for a National Theatre of Scotland to be established. There is room to question whether the modern national institution has a greater popular impact than the grassroots initiatives that laid its foundations decades earlier.

What stands out from all this activity is the strong interplay between people active across Scotland’s cultural scene, so that poetry, playwriting, singing, dancing and performing all helped to support and sustain each other. Lochhead and Marra were exemplars of this new mode of cultural fusion and multi-tasking. In Glasgow, venues such as the Third Eye Centre, run by Tom McGrath, another Arts Council victim, and the famous folk venue, the communist Star Club, played important roles in supporting cultural activity, as did pubs such as Sandy Bells, The Royal Oak and the West End Hotel bar in Edinburgh, as well as The Scotia Bar in Glasgow.

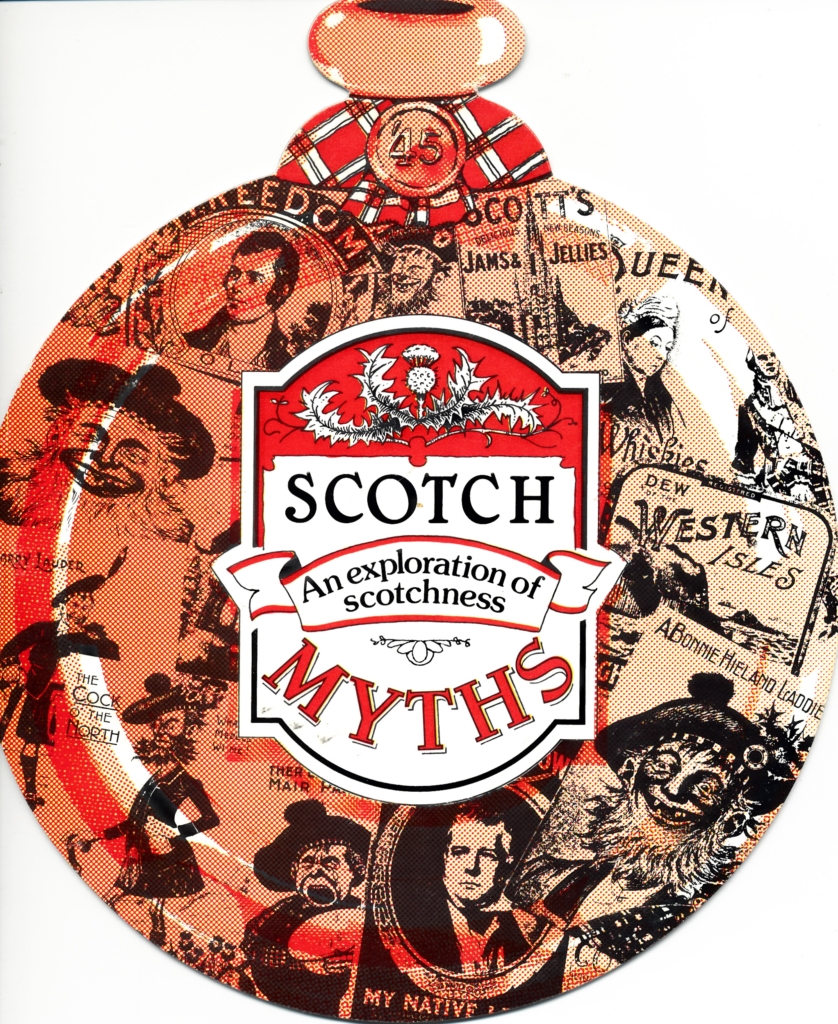

Other cultural events were to provide debate and discussion about what exactly constituted Scots identity. In spring 1981, the Scotch Myths exhibition, devised by Murray together with Barbara Grigor and Peter Rush, was mounted at the Crawford Centre at the University of St. Andrews. It went on to feature in the Edinburgh International Festival later that year. Its exploration of popular representations of Scottish identity, focusing on Tartanry and the Kailyard, attracted much critical attention and influenced cultural and political debate in the early 1980s.

Scotch Myths, @ Murray Grigor

In the spring 1981 issue of The Bulletin of Scottish Politics, four articles were devoted to themes explored by the exhibition (40). Colin McArthur also reviewed the exhibition in the winter 1981-82 issue of Cencrastus (41), the first of a substantial series the magazine ran on the representation of Scotland and the Scots in the media. The exhibition also inspired the three-day Scotch Reels event held at the 1982 Edinburgh Film Festival, which explored representations of Scotland and the Scots in both cinema and television (42). Grigor later contributed to Scotch Reels: Scotland in Cinema and Television, edited by Colin McArthur (43) and was commissioned to write and direct the film Scotch Myths, which was screened in March 1983 at the Festival of Film and Television from the Celtic Countries, held in Glasgow (44). In the end tartan, along with piping and accordions, and to a lesser degree kailyard, were taken to be acceptable in the smorgasbord that now constituted contemporary Scotland, an outcome which perhaps caused MacDiarmid to spin a bit in his grave.

Another challenge to the previously narrow conception of identity arose out of Billy Kay’s Odyssey: Voices from Scotland’s Recent Past. Published by Polygon Books, the student arm of Edinburgh University Press, in 1980 (45) this was a ground-breaking collection of oral history drawn from his popular Odyssey radio series broadcast by BBC Radio Scotland the previous year. The work captured the diverse experiences of men and women across Scotland, including migrants from Donegal, Kintyre fishermen, Lithuanians in Lanarkshire, Dundee jute workers, Shetland whalers, Tiree emigrants to Canada, and servicemen returning to Knoydart after the Second World War seeking to exercise their land rights. It reflected a view of Scotland as an inclusive and ethnically diverse national polity, what William McIlvanney was later to describe as a ‘mongrel nation’ in his famous speech to the 20,000 strong crowds at the Campaign for Scottish Democracy rally in Edinburgh in December 1992 (46).

Scottish broadcasting also made its own contribution. The changing expectations and aspirations of young women were addressed in the BBC television drama series Maggie, based on novels by Joan Lingard published in the 1970s. Set in Glasgow and Inverness-shire, the series centred on teenager Maggie McKinley and the challenges of adolescence as she aspired to further education, a career and an independent life, while her parents’ expectations for her were a secure job, marriage and settling down. Broadcast in a peak viewing early-evening slot from 1981 to 1982, it had a strong cast, including Kirsty Miller, Mary Riggans, Jean Faulds and Michael Sheard, with the title music written by B.A. Robertson.

Kirsty Miller as Maggie @ Radio Times

As will be obvious from this review, Scottish politics in the early 1980s was still predominantly a male preserve, and political parties were to spend decades arguing and debating how best to ensure proper representation of women (47). In this, as in much else, the parties tended to be well behind the curve of social and cultural change. The perspectives of women were to become increasingly prominent across the Scottish political discourse as this wrangling continued. The CSA also had its own internal difficulties to overcome in respect of gender equality, leading at one point to a female walkout. The final blueprint issued by the Constitutional Convention was still considered something of a poor compromise by feminists (48).

And then there were the magazines in which many of these personal and political linkages and inter-connections were played out. It was the magazines that highlighted, reported on and critiqued the vibrant mix of art, culture and politics, seeing this blending and complexity as the new norm. Those writing the plays, poems and books and making the music were also involved in publishing and contributing to the various discourses offered by these magazines.

In his novel, And the Land Lay Still, James Robertson highlighted the importance of small magazines in framing these political and cultural discourses in the period between the referendums. Robertson had been a long-time member of Radical Scotland’s board:

“There were magazines recording and encouraging this process of self-exploration. They were small-scale, low-budget, sporadic affairs, and their sales were tiny – a few hundred, a very few thousand – but the people running them weren’t doing it for the sales. They were doing it to address that pervasive sense of wrongness. And the people who read them – culturally aware, politically active people – were hungry for what they provided. More than anything, perhaps, the magazines said: “You are not alone.” (49)”

One of the first out of the blocks was the literary and cultural affairs magazine, Cencrastus. Launched in autumn 1979 by a group of Edinburgh University students with the support of Cairns Craig, then a lecturer in the English Department, its expressed intention was to perpetuate the devolution debate within an internationalist frame (50). In some ways, it picked up where its predecessors like Scottish International and Calgacus had left off.

The pro-self-government radical quarterly Crann Tara had been run almost single-handedly from Aberdeen by Norman Easton since 1977 (51). At its supporters’ group (52) meeting in February 1981, it was agreed to move to Edinburgh, with Easton staying on as editor for one more year (53). When Ian Dunn took over as editor in 1982 the magazine was renamed Radical Scotland (54).

The following year it was relaunched as a bi-monthly magazine under the same title, by a predominantly new editorial team headed by Kevin Dunion (55). Most members of that new team, including Dunion, had previously been involved with the 79 Group News and, with the demise of the Group, were looking for a new vehicle to promote their particular political perspective. The magazine was to later spearhead the notion of the ‘Doomsday Scenario’ in the run-up to the 1987 general election, whereby Scotland would again vote Labour but again receive a Tory government based on English votes. It also promoted the idea of the Constitutional Convention and became the house magazine for the CSA debates, arguments and thinking. Radical Scotland, although very much a political publication, also gave a great deal of space to cultural matters, reviewing books, plays and music as well as commissioning and publishing short stories and poems.

Autumn 1980 also saw the launch of The Bulletin of Scottish Politics. Though very short-lived – its second and final issue appearing six months later in Spring 1981 – it was influential in shaping the character of the campaign which followed. Its Editorial Board comprised Neal Ascherson, Jack Brand, Bernard Crick, Roy Grønneberg, Christopher Harvie, Tom Nairn, Lindsay Paterson, Danus Skene and Michael Spens, all of whom had been active in the Yes Campaign of 1979.

Their stated position was that there should be a Scottish Assembly, given that the question had been fully debated across Scotland and answered in the affirmative. The question for the 1980s was, therefore, what road the self-government movement should now take. Their political stance was to the left, again reflecting the preference which the Scottish electorate had expressed at the 1979 General Election. It was also, like the other magazines, internationalist in outlook, keen to see how the loosening of the monochrome post-war political landscape would alter previously long-held allegiances and national constructs and identities. Here the writings of Gramsci, then just recently published in English by Hamish Henderson, were an important contribution to that thinking, as were the plays of Václav Havel and Dario Fo. As a group, these magazines ensured that the focus on Scottish identity and culture would play an important part in building national self-confidence and help overcome debilitating party political divisions (56).

Looking back

In the early 1980s, the absence of clear and effective leadership from the main political parties created a vacuum that activists filled by pursuing their own initiatives, building on the cross-party links which had been forged during the run-up to the 1979 referendum. This process was further facilitated by the establishment of various interest groups and umbrella organisations, such as the CSA. The organisation and execution of demonstrations and events helped further bind people together, as did the discussion forums offered at various venues, and by small political and cultural magazines.

Activists recognised that a confident and vibrant contemporary culture could help to advance the cause of self-government, taking inspiration from similar developments across Europe at that time. The period also saw a final cathartic rejection of the couthie tartanry which had served to sustain and contain Scottish identity during the heyday of Empire, though tartan itself was to survive as a strand within that emerging new cultural fabric.

In the period between the referendums there was the consolidation of modern civic nationalism: the idea of Scotland as an inclusive, ethnically diverse and socially progressive national polity. This became a pervasive political narrative, reshaping notions of nationalism and national identity. And, of course, this is a narrative now being rightfully challenged and tested, as was the case with the previous myth-making. The small magazines played a significant role in that cultural project through the exploration of neglected areas of Scotland’s cultural and political history, and by publishing and reviewing emerging thinkers and writers. Their international connections helped to frame Scotland as a legitimate national polity, as well-equipped to pursue progressive agendas as any of its European neighbours.

That said, traditional party politics in the early 1980s was still very predominantly male, though the perspectives and participation of women were becoming increasingly prominent across the Scottish political scene. Wider developments in both the social and cultural realms played an important part in challenging and displacing male chauvinism in its various guises.

Universities also played a major role in the re-thinking and re-shaping both of politics and culture by providing spaces for these discussions to take place, funding many of the publications that emanated from these debates and paying the wages of many that engaged in them. In the 1980s, many students also still had the time and finances to fully engage, participate and agitate. That world has long gone, and today Scotland’s universities are turning their backs on their role as depositories of knowledge, thought, argument and culture, finding it more congenial and financially rewarding to present themselves as corporate drivers of the neo-liberal project.

Debating Chamber, Scottish Assembly @ Behind Closed Doors

And then there is that old High School building, which after 40 years, might finally have found a purpose, not as a parliament but as the new home for a music school. While self-government activists and Tory ministers were acutely aware of the potential of the empty Assembly building as a focus for discontent about Scotland’s political predicament, party leaders for their own sectional interests fought shy of exploiting that potential. Our own engagement with the building, forty years ago this month, fell short of our hopes; but together with subsequent events, including demonstrations staged on Calton Hill by the CSA and Democracy for Scotland’s five-year vigil in the 1990s, it probably contributed something to the narrative of democracy denied. And that was, of course, the basic premise that drove the campaign for a Scottish Parliament to its ultimate success.

Footnotes

- Wilson, G (2009) SNP: The Turbulent Years 1960 – 1990. Stirling: Scots Independent, 201 – 218

- McLean, B (2005) Getting it Together: The History of the Campaign for a Scottish Assembly/Parliament 1980 – 1999. Edinburgh: Luath Press Limited, 40 -73.

- McLean, op cit.

- McLean, op cit.

- Ascherson, N (1980) ‘After Devolution’, The Bulletin of Scottish Politics, No. 1, September, Edinburgh, 1-6.

- Foulkes, G (1981) ‘Labour for an Assembly’, Crann-Tara, No. 12, Winter, 7.

- ‘Labour at Perth’, op cit.

- Boyack, Jim (1981) ‘No Mass Movement: Wheeling and Dealing for a Scottish Assembly’, Crann-Tara, No. 15, Autumn.

- ‘Livingston – The Great Strategy Debate’, 79 Group News, Issue 1, March 1981, 4.

- ‘The Long March’, Crann-Tara, No. 13, Spring, 5.

- ‘Lee Jeans Rally’ and ‘Buroo Demos’, 79 Group News, July-August 1981, 1 and 2.

- Wilson, op cit.

- ‘Continued Swing to the Left: Stirling National Council’, 79 Group News, July-August 1981, 3.

- ‘Royal High School Protest’, 79 Group News, September 1981, 1.

- Purves, G (1982) ‘Calton Hill Break-In’, Radical Scotland, Issue 1, Summer, 12-14.

- ‘Assembly Occupied’, 79 Group News, October 1981, 1.

- Purves, op cit.

- Thomson, C (1983), ‘The Anglicisation of Scots Law’, Cencrastus, No. 12, Spring, 2-5.

- Sillars v Smith SLT 539, Second Division held that the vires of an Act of Parliament could not competently be challenged in a Scottish Court.

- University of Stirling, Scottish Political Archive records.

- Dunion, K (1982) ‘Ayr Revisited’, 79 Group News, August, 6.

- Wilson, op cit.

- Wilson, op cit.

- Maxwell, S (1982) ‘Radicalism without Ideology?’, 79 Group News, August, 7.

- Skene, D (1981) ‘Behind the Gang’, Crann-Tara, Number 13, Spring, 16 – 17.

- McLean, op cit.

- McLean, op cit.

- McLean, op cit.

- Craig, C (2018) The Wealth of the Nation: Scotland, culture and independence. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Nairn, T (1973) Culture and nationalism: An open letter from Tom Nairn, Scottish International, Vol. 6, No. 4, 3.

- Craig credits Edwin Morgan as being the apostle of ‘theoxenia’, diligently reworking Scotland’s past in ways that would allow her to engage on equal terms with other European cultures. Morgan’s notion of the gifts of gods who come as strangers; is an allusion to his translation of Friedrich Hölderlin’s; The Rhine; which sees the gods as wandering about among us, seeking what immortality denies them – emotion, sympathy, identification. Thus any stranger might be Zeus in disguise, so we should welcome them and value their gifts.

- Hames, S (2020), The Literary Politics of Devolution. Voice, class, nation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Craig, C (1981) ‘Going down to Hell is easy’, Cencrastus, No. 6, Autumn, 19-21.

- Bernstein, S (1999) Alasdair Gray. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 18.

- Kerevan, G (1983) ‘The cultural consequences of Mr Keynes’, Radical Scotland, August/September, 23-26.

- Gibson, R (2020) Reclaiming Our Land. Highland Heritage Trust, 43.

- Munro, A (1996) The Democratic Muse: Folk music revival in Scotland. Aberdeen: Scottish Cultural Press.

- Alan Stivell, a Breton and Celtic musician, who through playing the harp, generated global interest in Celtic music as a component part of world music.

- Stevenson, R (1981) ‘Scottish Theatre Company: First days, first nights’, Cencrastus, No. 7, Winter, 10 – 13.

- ‘The Politics of Tartanry’, The Bulletin of Scottish Politics, No. 2, Spring 1981, 55-86.

- MacArthur, C (1981) ‘Breaking the Signs: 'Scotch Myths' as Cultural Struggle’, Cencrastus, No. 7, Winter, 21-25.

- McArthur, C (1983) ‘Scotland: The Reel Image: Scotch Reels and After’, Cencrastus, No. 11, New Year, 2-3.

- McArthur, C (ed.) (1982), Scotch Reels: Scotland in Cinema and Television. London: BFI Publishing.

- McArthur, C (1983) ‘Tendencies in the New Scottish Cinema’, Cencrastus, No. 13, Summer, 33 – 35.

- Kay, B (1980) Odyssey: Voices from Recent Scotland’s Past. Edinburgh: Polygon Books.

- William McIlvanney: Scottish author known as the ‘godfather of tartan noir’ who also articulated the struggle for independence, The Times, 7 December 2015.

- McLean, op.cit.

- Breitenbach, E and Mackay, F (eds) (2001) Women and Contemporary Scottish Politics. Edinburgh: Polygon.

- Robertson, J (2010) And the Land Lay Still. London: Hamish Hamilton

- Gunn, L and McCleery, A (2009) ‘Wasps in a Jam Jar: Scottish literary magazines and political culture 1979-99’, in A McNair and J Ryder (eds.) Further from the Frontiers: Crosscurrents in Irish and Scottish Studies. Aberdeen: Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen.

- Crann Tara (1980) ‘Supporters take over Crann-Tara’, Crann-Tara, No. 10, Spring, 7.

- Crann Tara (1980) ‘Supporters take over Crann-Tara’, Crann-Tara, No. 10, Spring, 7.

- Crann Tara (1981) ‘Supporters’ Meeting Report, Crann-Tara, No. 13, Spring, 2.

- Dunn, I (1982) Radical Scotland: A Socialist Quarterly, No. 1, Summer.

- Dunion, K (1983) Radical Scotland, February/March.

- ‘Presenting the Bulletin of Scottish Politics’, The Bulletin of Scottish Politics, No. 1, Autumn 1980, i-iv.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

Thanks, Douglas and Graeme, for such a comprehensive review and such a valuable ‘insider’ activist longue durée perspective. Much to reflect on and discuss further and an excellent reflective framework for just such a debate.

Many thanks for these kind words Ray!

Top analysis of Sotland re discovering itself….a neccesary step towards independence. An observation …only Jim Sillars and George Galloway have publicly survived the period detailed.

I listened to an unbowed and relevant Jim Sillars at the Alba conference fringe in Greenock.

Before the referendum, I attended an event where the speakers were Jim Sillars, Colin Fox and Maggie Chapman.

It was well attended, in Leith Town Hall I think, and the speakers were all very good.

I seem to recall Jim Sillars defending the SNP against a couple of radical audience members – changed times!

Thanks for this article – really interesting.

One small point: Malcolm Middleton would still have been in short trousers in the early 80s. Arab Strap’s debut album was ‘96 and Malcolm’s first solo album was 2002.

You are right, my mistake and prejudice. That voice and its authenticity have always got me.

Thank you very much indeed Graeme and Douglas. I’m a now auld socialist, and spent much time and effort from the 1960s onwards working hard for a (devolved) Scots Parliament – but I now understand from experience of trying to work with that limited Parliament in its early years, that ‘devolution’ is simply not enough. I find your work chimes on almost every carefully-examined and referenced detail with my own experience. (I’m currently researching and writing my own political memoir, provisionally titled “Mair nor a roch wind” – from Hamish Henderson’s famous song-poem of course. From 1968 to 1990, I was largely as a self-trained member of the Communist Party. So you may imagine my wee political journey!

Indeed, the only work I have read, and which I consider pretty helpful, to which you don’t refer, is Ben Jackson’s thin but scholarly 2020 work “The case for Scottish Independence; a history of Nationalist Political Thought in Modern Scotland”, Cambridge University Press.

I was privileged to work for many years (1976-1990) as economist for the Scottish Trades Union Congress, so lived through, and helped the STUC contribute to (I hope!) at least some of the processes and developments you outline. I was very glad indeed to read that the two of you at least understand something of the significance of the STUC, led initially by its fine (Aberdonian) General Secretary Jimmy Milne, to the ‘wee pretendy parliament’ we now enjoy. Whose creation did indeed help create wider understanding of our need for independence.

Lang may baith yer lums reek!

Many thanks for these kind comments Dougie!

This is a very good article and provides valuable information about the early role of the role of Socialists in the SNP by participants in the events. It is particularly good at linking political and cultural activities.

This would be good published as part of a pamphlet.

Ray Burnett (a contribuior to the first Red Paper) could provide a good account of the post1968 Left in Scotland and its engagement with Scottish history and culture.

Neil Williamson, who unfortunately died early in 1979, also wrote Ten Years After – the Revolutionary Left in Scotland in the Scottish Government Yearbook 1979. Another International Marxist Group member, at the time, George Kerevan. also wrote Arguments within Scottish Marxism in the Bulletin of Scottish Politics No.2, 1981 (a journal mentioned in Douglas’s and Graeme’s article)

The IMG went on to join Jim Sillars’ Scottish Labour Party, but there also were others, e.g. Bill Scott who could also probably write about the SLP contribution to Scottish Left politics.

Somebody who was involved in the socialist republican magazine, Liberation, could also make a worthwhile contribution for the later years of Socialist activity in the SNP.

I have made my own contribution, which covers a section of the revolutionary Left in Scotland from 1968 to the present day, including the experience of the SSP, in From Grey to Red Granite.. This can be read at:-

https://allanarmstrong831930095.files.wordpress.com/2021/08/from-grey-to-red-granite-3.pdf