Platform Workers Plan Big Move

Ask folk in Scotland’s capital if they can describe any of the Edinburgh’s ‘big moves’ and they might mention the reopening of the St James Centre last year, the relocation of the Scottish Parliament back in 1999, or maybe even the shift of the city’s wealthier denizens to the New Town in the 1800s.

They probably won’t mention the 9 ‘big moves’ that were published last month as part of the framework for the £1 billion City Deal in Edinburgh and South East Scotland (ESES for short).

The ESES City Deal is a 15 year plan involving the Scottish and UK governments as well as the region’s universities, to ‘accelerate growth, create new economic opportunities, and meaningful new jobs’ [sic]. The first ‘big move’ on its grid is to make Edinburgh the ‘Data Capital of Europe’.

A reader of the report might suspect that the architects of the City Deal have some delusions of grandeur. ‘The ESES region was home to the Scottish Enlightenment’, they declare, ‘and now has a unique opportunity to build on the investment from the Data Driven Innovation programme.’

The Scottish Enlightenment, the flourishing of ideas and innovation in the eighteenth century that unleashed new methods in science, history, and economics, seems a rather hyperbolic parallel.

But the comparison is made by historians too. In a 2019 book called Enlightenment in a Smart City: Edinburgh’s Civic Development, 1660-1750, Murray Pittock represented Scotland’s eighteenth century capital in modern terms of innovation, connectivity, and other ‘routers of change’.

Civic development was pioneered by city politicians and officials, lawyers, academics, doctors, planners, and other professionals, Pittock claims, whose ‘association, hybridisation and fusion’ created a ‘cross-cutting generation of ideas that provide the infrastructure of the Enlightenment’.

This assemblage of eighteenth-century anecdotes into an arduous analogy of a modern ‘smart city’ almost reads like a tribute to the boards and civic committees of the City Deal.

But whether we read the historian of the eighteenth century or the planners of the twenty-first, there is something missing from this melting pot. The workers of the city.

Professor Pittock’s book has plenty of details about the regulation of muckmen and coachmen, the couriers and cleansing workers of their day, but hardly a mention of their own innovations and agency.

Yet the Society of Cadies, the forerunners of today’s delivery drivers and riders, developed their own system of regulation and rates that gave them control over their routines in the burgeoning city.

Returning to today, the City Deal passage about Enlightenment continues: ‘We must embrace the spirit of innovation found across our communities and businesses and direct this to solving a wider range of challenges’.

But where communities and businesses are active agents, the only mention of workers is entirely passive – things are done for them and to them, not by them. And there is not a single mention of trade unions or workers’ associations in the whole 50-page document.

Yet for workers in the city the experience of innovation and the impact of Data Driven Innovation has a massive effect on life. The algorithmic allocation of work and pay programmes the inequalities and economic opportunities that the City Deal declares as its mission to improve. And workers are also finding smart ways to solve the problems of platform exploitation.

Take a Deliveroo rider who works on a data-driven platform. Their rates of pay and working time are calculated with data that is first taken from the rider, then hidden from them. It is extremely difficult for these couriers to make contact with other riders to build up the collective knowledge and skills to challenge poor conditions in the gig economy. They too need infrastructure and innovations to improve their power at work, and their ability to turn gig work into a better economic opportunity.

The same goes in care, construction, tech work, and many other sectors where data-driven change is advancing fast and shifting more and more power to those in command of the data and technology.

Fortunately, workers are not waiting for the City Deal to make a ‘big move’ in their interest. The Workers’ Observatory is an initiative of gig workers to monitor the way that work is changing due to data. In Edinburgh and across the world, workers in the digital and platform economy are conducting their own inquiries into data-driven change, meeting data driven innovation with worker driven innovation.

This week, the Observatory is supporting an international event called ‘Digital Worker Inquiry’, that brings together workers, researcher, and union organisers to explore innovations and infrastructure being developed from the bottom up to empower workers to take matters into their own hands.

It will showcase projects from around the world: a Chilean initiative for workers to gather stories about changing experiences of data-driven work, a Georgian tool to calculate wage theft, and an Edinburgh-based app for delivery riders to monitor pay over time. These kinds of worker driven innovations are enabling couriers, care workers, rubbish collectors, coders, and construction workers to come to terms with the Data Driven agenda that is transforming work in every city on the globe.

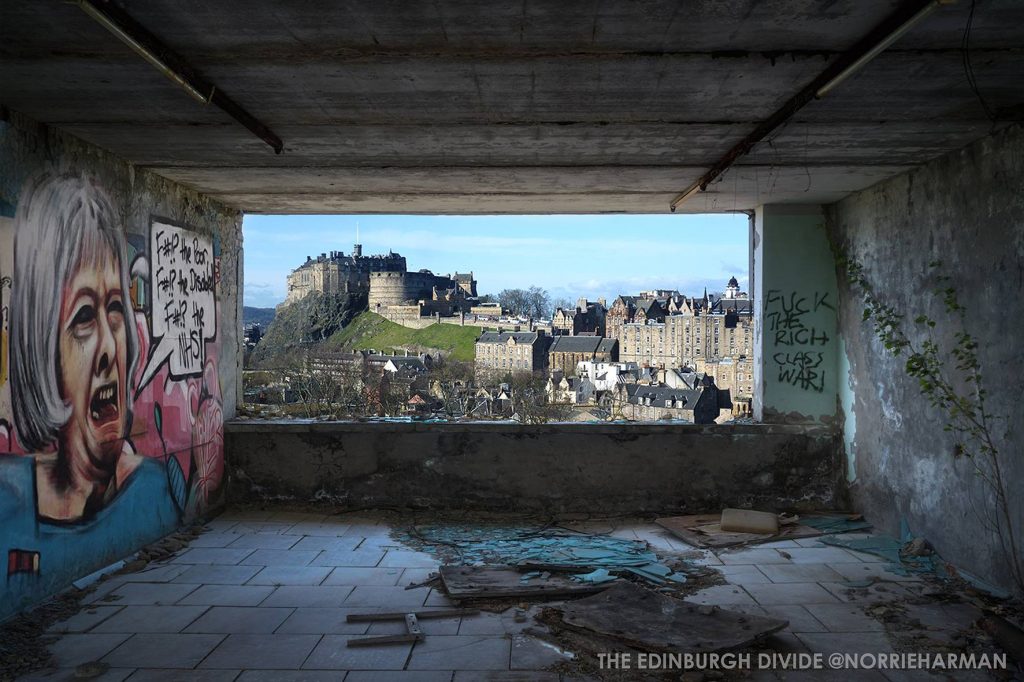

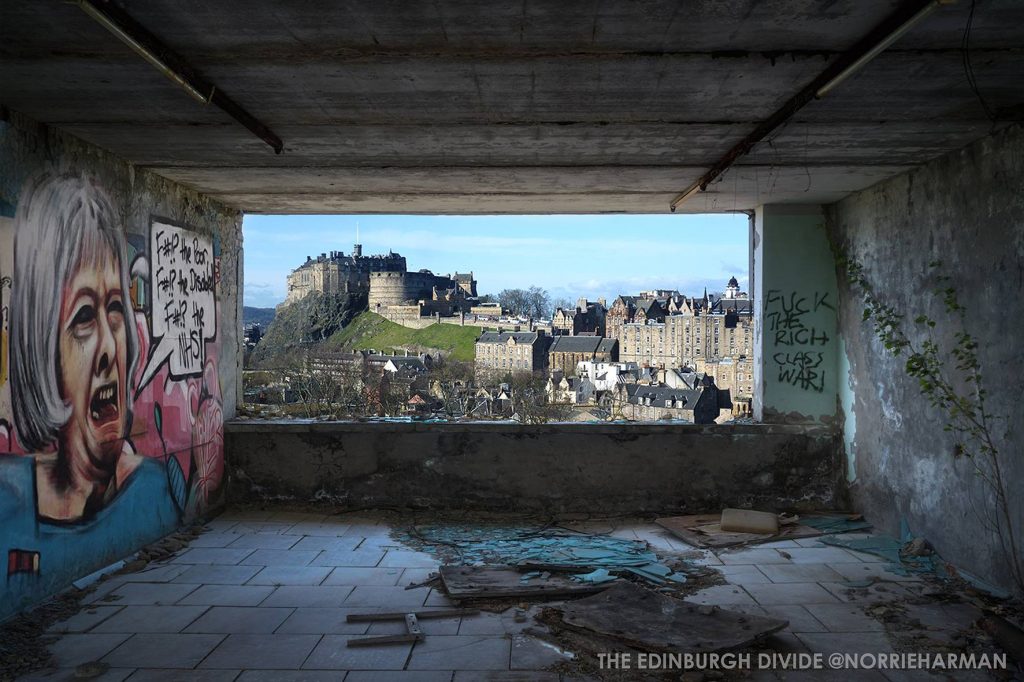

Platform workers in Scotland’s capital see every facet of the city but they are often unseen. They will probably not be surprised to be missing from the ‘big moves’ grid drawn up by the City Deal leaders and planners. But they are developing plans to make some big moves of their own.

sounds like a good start but eventually all workers, including freelance, should have access to relevant data. For example freelance workers could have realtime access to current rates plus bad and good clients. Similarly for office workers. The normal grapevine is too slow and too limited.

Still, we all have to start somewhere.

I had a look at the tech guild page:

https://workersobservatory.org/tech-guild/

Years ago, I attended some (very helpful and friendly) meetings of a tech-worker association created by and solely comprising of workers in a specialised area, and cutting across Scottish university and college education sectors. Although there were some conversations about terms and conditions, the main concerns were around sharing best practice, something management tended to discourage, sometimes oppressively (citing improbable competition and commercial exploitation of intellectual property reasons, in my experience). The global tide was starting to turn by the time I left (for example, NASA has thrown its weight behind open science, technology and data).

I don’t know what the picture is in the Care and Delivery areas, but I believe sharing of best practice (that is, idea communism) should be as central to the Tech Guild as pay and conditions, and collective bargaining could be used to force open the standard contracts of employment, particularly those clauses which prohibit sharing of technology or make intellectual property claims on behalf of employers on the out-of-hours work of employees. Learn one, learn all.