The Politics of the Environment

The first in a series of Bella Classics – reviewing and reflecting on classic Scottish texts. Here we look at Malcolm Slesser,The Politics of Environment: A Guide to Scottish Thought and Action – Books from Scotland, 1972.

The fractious debate over the merits of exploiting the Cambo oilfield to the west of Shetland is a reckoning for Scottish nationalists. Suddenly, the certainties that grounded the economic case for independence are being challenged by the urgent responsibilities of environmental action. For half a century, the SNP’s economic doctrine has centred on the benefits that hydrocarbons in the North Sea could provide for citizens of an independent Scotland, if only the electorate was willing to seize the opportunity. When we think back to the nationalist electoral breakthrough of the early 1970s, the slogan ‘It’s Scotland’s Oil’ stands out as the dominant feature of SNP campaigning in the period of Ted Heath and Harold Wilson’s governments over the first half of the decade.

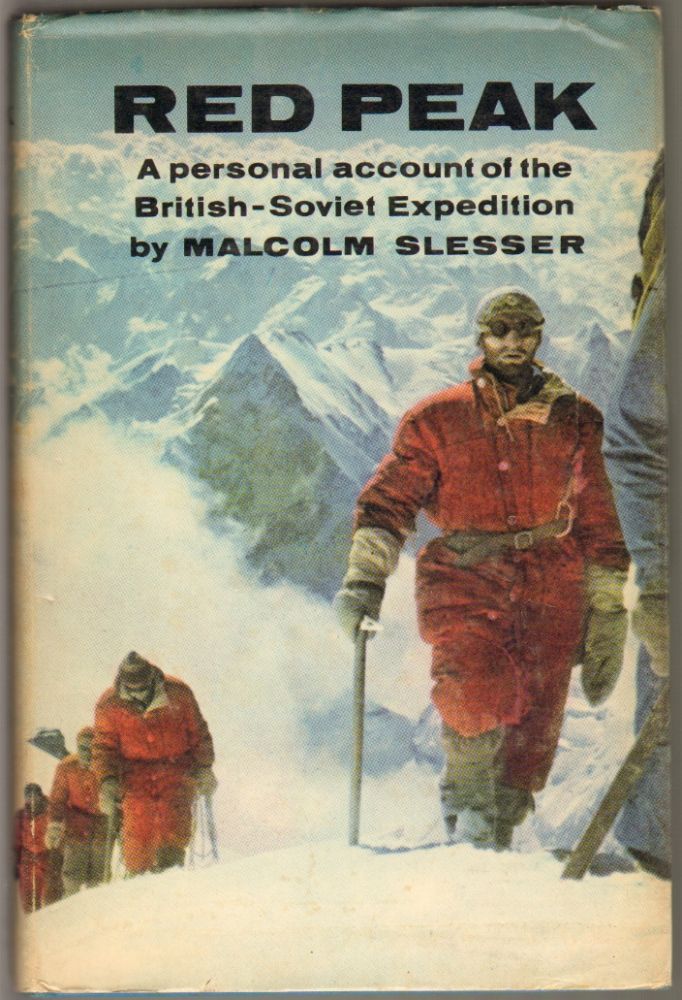

Yet just as the SNP’s oil campaign was taking off, one of the party’s senior members was devising a very different understanding of Scotland’s natural resources. Malcolm Slesser was perhaps best known in his lifetime as a mountaineer who helped lead a famous Anglo-Soviet expedition to the Pamirs in Central Asia in which two of his comrades perished. He was also a natural scientist and an energy analyst who worked at Strathclyde University.

Slesser’s The Politics of Environment is a stark warning about the need for urgent action to avoid environmental catastrophe. It is Slesser’s contention that the insatiable appetite of capitalist societies for ever growing quantities of resources will lead to calamity. In terms that seem only too resonant during the run up to the COP26 summit, he warned his readers almost fifty years ago that ‘our self-destroying sabre-tooth, is industrialisation. The excellent servant is a deadly master.’ Not one to mince his words, Slesser prophesised ‘an inevitable reckoning with the biological requirements for continued existence on the globe.’ From our current juncture, we can only wish that Slesser’s forceful prose had had an equally forceful impact on his contemporary world at large.

These perspectives are very much a product of the radical political context that developed during and soon after 1968. In the introduction, Slesser emphasises that conservationism and environmental concern should be understood in a society being rocked by ‘affluent strikers’ dissatisfied with factory assembly lines and student protesters animated by solidarity with third world revolutionaries. There are shades of Herbert Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man in these observations. Slesser locates workplace discontent as well as in growing social movements raging against nuclear power and even demonstrations against the Concorde supersonic plane project in the alienation endured by workers and citizens who have lost their status as craftsmen and purveyors of the democratic intellect.

A strong rejection of materialism informs The Politics of Environment. Both ‘the Old Left’ and trade unions are criticised for their faith in the boundless development of the productive forces and promotion of resource burning and environmentally devastating technologies. Slesser also rejects the politics of class struggle as corrosive and promoting the ‘unwarranted centralism’ of the planner state. Instead, Slesser advocates a form of ‘international socialism’ centred on ‘interdependent communities’.

Scotland is in an opportune position to take the lead in this societal transformation. As a small nation with bountiful resources, Scottish society could relatively easily live in ‘balance’ with the environment. In Slesser’s view Scotland has also developed the egalitarian cultural potential to undertake the necessary political changes, if only it is willing to break with the British state and its ‘industrial colonialism’. If anything, Scotland is in fact underpopulated. Slesser concludes that a population of around six to seven million would best serve the nation and condemns the extent of emigration, especially to England. This was a commonplace nationalist and trade unionist complaint at the time. These grievances often centred on critiquing Scotland’s lack of advanced industrial capacity. Slesser on the other hand condemns the British government’s direction of mass production to Scotland, viewing it as ruinous and trapping the Scottish economy under foreign domination.

If Scotland is presented as a potentially positive case, England is viewed as the prime example of a ‘pathologically overdeveloped’ society ‘committed to overpopulation, over-industrialisation and racial problems’. Slesser points to England’s lack of natural resources and its high levels of population density as reasons for its unviability in terms redolent of ‘cybernat’ contentions about Scotland’s water supplies. He also points to England’s emergent racial diversity as a source of social strife, contrasting it with Scotland’s smaller, more homogeneous population. This underlines Slesser’s contention that ‘small advanced nations’ are the beacons of the future and that Scotland is ‘the only practically salvable community’ within the United Kingdom.

It would be convenient to isolate Slesser’s contention on racial diversity or his catastrophist argument about the rest of the UK, and other large industrial nations, being doomed as logical conclusionism or simply redundant from his wider thesis. That would also be sophistry though. Slesser’s entire contention is centred on the role of small communities in resource rich environments. One is left wondering what he saw for the majority of the world’s population and indeed the planet as a whole, given the only way to reverse the processes he rightly saw as causing environmental devastation would be through societal change in the world’s biggest economies.

Another uncomfortable element of The Politics of Environment is Slesser’s insistence that overpopulation is a leading cause of environmental hazards. He hyperbolically claimed that the world population could grow to 30 billion by 2075. These contentions are accompanied by an environmental perspective centred on resource exhaustion. Slesser also warns his readers that oil supplies would be exhausted by the end of the millennium. He cites the influence Club of Rome Limits to Growth report in support of his resource exhaustion argument. Limits to Growth was published the same year as his book which galvanised the nascent global environmental movement.

There are two important distinctions with much contemporary left-wing environmentalism in this outlook. The first is that in the debate over the so-called Anthropocene – the geological era dominated by human activity. Marxist historians such as Andreas Malm have contended that in fact it is the dynamics of capitalist accumulation and not population change that has driven climate change. Rates of carbon emissions grew a hundred times as fast as population change over the last two centuries. Secondly, Slesser’s perspective on resource exhaustion seem quaint in the context of the debate over Cambo. The problem isn’t the finite nature of carbon resources just now, it’s the fact that there’s clearly enough to make the planet uninhabitable.

Slesser was enthused by the discovery of North Sea oil, asserting that domestic reserves would allow Scotland to become ‘one of the few European nations, had she her own government, independent of imported oil.’ Along with purchasing as many saltires as they could carry, he also advised his readers to ‘buy Scottish’, especially from Burmah Oil Company which was then still a Scottish owned firm. For an advocate of the liberty of small nations, Slesser seemed less concerned by the company’s colonial roots in the Rangoon oilfields.

The Politics of Environment deserves to be understood as a major text in the development of Scottish nationalist perspectives on the environment, capitalism and natural resources. Slesser was an authoritative figure and he was alert to the fundamental incompatibility of boundless fossil fuel driven consumption. His criticisms were also socially grounded, alert to the discontents of late industrial society. On the other hand, his work also demonstrates some of the fundamental weaknesses of trying to pursue environmental transformation through a nationalist lens.

His efforts to ground global concerns in the Scottish context and develop an esoteric national perspective are commendable but the overlap into reactionary views on cosmopolitanism are more than just unfortunate. They raise important questions about Scottish nationalism’s assertions over the virtues of small nations. Slesser’s book is also very much an artefact of time and place in terms of its perspective on the foundations of the environmental crisis. He saw the key questions as relating to population levels and imbalances with available and finite natural resources. Petroleum and coal burning weren’t the key problems for him whereas they very much are for us.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

Thanks for this. I was unaware of much of this context when I took his energy economics course through CHE in early 90s. The course did give me a perspective of the fundamentals that have helped me steer through the froth of debate ever since.

As the importance of climate change became evident, Malcolm Slesser’s ideas moved on. I strongly recommend `Not by Money Alone’, co-written by Slesser and Jane King, published in 2002. A core idea of that book is that we should shift taxes onto energy.

Their thinking on living within the planet’s natural limits also to quite an extent anticipates Kate Raworth’s excellent `Doughnut Economics’.

Two other comments. Population may not have risen as fast as per capita carbon, but the two effects multiply: the biomass of animals on the planet is now 40% people, 57% domesticated animals, and only 3% for the rest; the resulting attrition of the natural environment and biodiversity is as serious a longterm problem as climate change. Secondly, there is a limit to the value of attributing blame for our predicament. In a sense, Andreas Malm’s contention that it’s the fault of exploitative capitalists is well-grounded, but the populations of the developed world are now used to the unsustainable lifestyle it’s led to; and we’re all going to have to work together to get to a better place.

Here’s hoping COP26 can turn a corner.

I Am 90 years old not educated in Scotland beyond lowers but i can understand that this article is saying that Scotland has no need for oil ! Scotland has wind and wave energy and more important than oil ever was it has an abundance of fresh water ! Man can live without oil but he cant live without water not only to drink but to grow crops .Scotland is surrounded by sea full of fish ,mountains made of granite to build cities like Aberdeen ,not to mention an intelligent and hard working population . There should be no need for food banks nor should there be people living on the streets ! This has happened because of the greed of people who are never satisfied with being multimillionaires they want to take every penny they can from the whole population . Boris Johnsons Hadrian wall should certainly be fortified as his poem suggests to keep out the lords and ladies and Baronesses and the likes who love the fact that they are being paid over £300 per day tax free from money paid in taxes by hard working people ! The sooner Scotland is independent the better!