Liverpool Calling – Phony Torymania Has(n’t) Bitten the Dust

Neil Cooper on the Tories crass attempts to resurrect their reputation on Merseyside and associate a new Beatles experience with “levelling up.”

I Read the News Today. Oh, Boy!

When The Clash released London Calling at the end of 1979, the politically charged title track of the first generation punk band’s third album sounded like one more much needed call to arms. Coming at the end of a year in which Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party was elected to government for what turned out to be eighteen years of misrule, the lyrics to Joe Strummer and Mick Jones’ composition were a lot to take in.

Police brutality, the partial meltdown of a nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island earlier that year, and the potentially apocalyptic consequences of the River Thames flooding were all in the mix. The song’s line ‘Phoney Beatlemania has bitten the dust’ also pointed up what was probably a first hand observation of the impotence of a rock band to be able to change things in the face of those who put faith in them.

Coming less than a decade after Liverpool’s 1960s pop saviours split up, the line was in keeping with punk’s willingness to question old platitudes, and slaughter sacred cows if need be. Forty-two years on, and if Strummer was still with us, one suspects he’d be as bewildered as anyone else by last week’s autumn 2021 budget announcement from Westminster Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak.

In a move welcomed by Nadine Dorries, the recently appointed Liverpool born Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, Sunak announced the sanctioning of a cool £2 million that will allow the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority to develop a business case for what Liverpool Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram described as “an immersive experience” called The Pool.

As outlined in The Guardian, The Pool aims to be much more than a new Beatles attraction, and will be what it describes as ‘an enormous and celebratory music hub which may have a new secondary school in it, rehearsal space for the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and other music education facilities’.

According to Liverpool City Council’s director of culture Clare McColgan quoted in the report, The Pool “will be huge and it will be much more than the Beatles.” She goes on to say that “what we are really excited about is how this gets kids from some of the poorest areas of Liverpool to create and explore their passion for music.”

According to Nadine Dorries, who supported the proposal, “If anything personifies levelling up, it’s the story of The Beatles. This funding will help unlock opportunities so that any child, no matter what corner of Liverpool they come from, or beyond, can become the next Lennon or McCartney.”

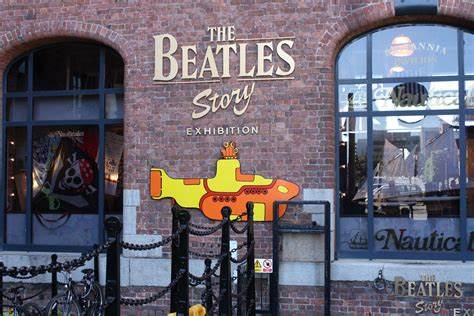

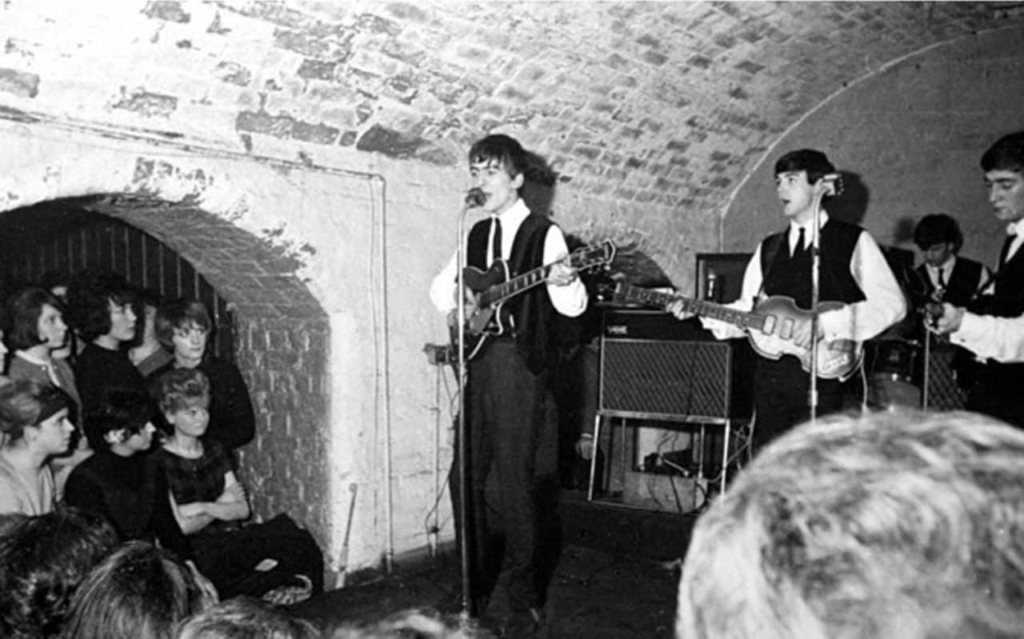

As fab-gear as such an initiative might sound, it has been pointed out elsewhere many times over the last few days that two Beatles museums already exist in Liverpool. One of these, The Beatles Story, is based at the revitalised Albert Dock, on the city’s waterfront. The other, Liverpool Beatles Museum, is on Mathew Street, where the loveable mop-tops played the original Cavern Club just shy of 300 times. The museum is a family affair set up by Roag Aspinall-Best, half-brother of the band’s original drummer Pete Best and son of Beatles road manager Neil Aspinall.

Both long-standing institutions bring considerable tourist money into the city as part of a high profile Beatles industry that keeps the band’s legacy alive. See the current incarnation of The Cavern Club, rebuilt close to the site of the original in 1984. See also the Hard Day’s Night Hotel, opened in 2008, the year Liverpool became European Capital of Culture.

It hasn’t always been this way. Back in the 1970s, as many of us who grew up in Liverpool at the time will be aware, the fertile network of coffee bars and cellar clubs that birthed The Beatles and a million other groups was in the process of being demolished out of existence. The original Cavern, a former jazz club based in an old fruit cellar, closed in 1973.

This followed the compulsory purchase of the basement premises in Mathew Street in order to build a new ventilation shaft for the new Merseyrail underground. The below ground cellar in the dilapidated warehouse lined alley was filled in, but the Merseyrail development never happened.

Meanwhile, the only formal monument to The Beatles at the time came in Four Lads Who Shook the World, a wall-based statue by Liverpool born sculptor Arthur Dooley. The statue depicts the Madonna holding four babies as she watches over Mathew Street opposite the site of one of the best-known music venues on the planet, which spent much of the next decade as a car park.

Liverpool Explodes

The demise of both The Beatles and The Cavern didn’t mean the city was bereft of artistic life. Nor was it likely to stop any time soon. Psychoanalyst Carl Jung had a dream in 1927 in which he imagined Liverpool – a city he never visited – as ‘the Pool of Life’. American Beat poet Allen Ginsberg picked up Jung’s hyperbole-laden baton in the 1960s to claim the city as the ‘centre of consciousness of the human universe’.

Neither of these notions was going away anytime soon. Especially not on Mathew Street, where in 1974 Jung’s notion of synchronicity inspired poet and artist Peter O’Halligan to open up an empty warehouse next to the former Cavern site as the Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun.

This bohemian arts lab was where in 1976 anarchic theatre director Ken Campbell presented his Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool production of Illuminatus!, a nine-hour staging of Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson’s sci-fi hippy conspiracy based trilogy of novels. The production featured a cast of Liverpool Everyman Theatre irregulars that included Jim Broadbent, Bill Nighy, Chris Fairbank and Prunella Gee, and a set designed by an art school dropout turned stagehand called Bill Drummond.

Campbell’s audacious epic was a smash hit, and was picked up by then National Theatre boss Peter Hall, who programmed it as the first play to be performed at the National’s newly opened Cottesloe space, later renamed the Dorfman.

The Liverpool School of Language, Music, Dream and Pun was also where a new band called Deaf School, formed at Liverpool College of Art, auditioned for former Beatles publicist Derek Taylor. Being where he was, the romance of another wonderful group from Liverpool apparently reduced Taylor to tears before he signed them to WEA Records. The three albums of art school glam cabaret released by Deaf School between 1976 and 1978 got lost in the stampede of punk, but their influence looms large, both in Liverpool, and in a musical legacy that has trickled into every inch of British pop music.

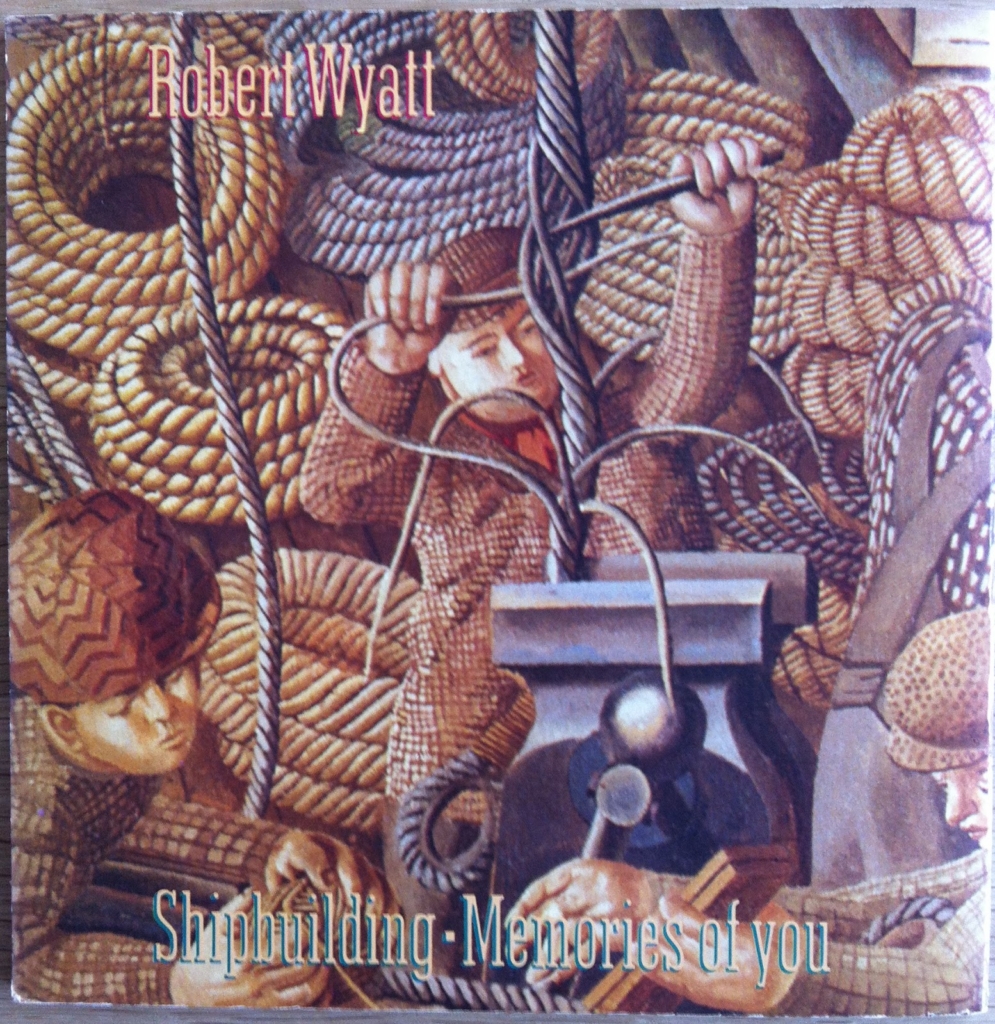

Guitarist Clive Langer’s productions of records by Madness and Dexys Midnight Runners defined their time, as did Robert Wyatt’s recording of Shipbuilding, an anti Falklands War elegy co-written by Langer and Elvis Costello. Deaf School co-vocalist Steve Allen, aka Enrico Cadillac Jnr, formed Original Mirrors with Ian Broudie, before moving into A&R and management, and gifting the world Gina G, singer of 1996 Eurovision chart topper Ooh…Aah… Just a Little Bit.

Allen’s fellow singer Bette Bright, christened Anne Martin, went on to make records as Bette Bright & the Illuminations, and recorded with Tim Finn. Sax player Ian Ritchie maintains his lengthy tenure touring with Roger Waters. Bass player Steve Lindsay appeared on Top of the Pops as The Planets with his mini hit, Lines, before moving into music publishing.

Keyboardist Max Ripple, real name John Wood, became Emeritus Professor of Design at Goldsmiths College at the University of London. And late co-vocalist Sam Davis, better known as Eric Shark, went on to co-found Probe Plus Records, which became the home of Birkenhead satirists Half Man Half Biscuit.

The Liverpool School was also home to Aunt Twacky’s Bazaar, an alternative market, where stallholders included Jayne Casey, Paul Rutherford and Pete Burns. In 1976, all three became regulars at a newly opened club across the road called Eric’s, whose co-founder and driving force Roger Eagle had sought them out to make the club their own, fostering a social experiment as he went.

Eric’s was named by fellow co-founder Ken Testi in reaction to those of faux aspirational dives with posh women’s names where you needed to wear a tie to get in. In a hard as nails inner city landscape with nowhere for them to go, Casey, Rutherford, Burns and others brought Eric’s to life, with their bands, their personalities and their outlandish appearance, just as The Beatles had done with the now seemingly long lost Cavern a decade earlier. Eric’s was their stage, a safe space where art and life rubbed up against each other with messy abandon.

Out of this, Casey became vocalist of Big in Japan, a band formed in May 1977 after Deaf School guitarist Clive Langer suggested it to Illuminatus! designer Bill Drummond, who became Big in Japan’s guitarist alongside a kid called Ian Broudie. Also in the band at various points were bassist Holly Johnson and drummer Budgie, who had played in a group called The Spitfire Boys with Rutherford. After Johnson was sacked, a new bass player called Dave Balfe joined.

Meanwhile, Burns had his own thing going on with his band, Nightmares in Wax, inbetween working at Probe, the underground record shop that had moved into premises a stone’s throw from The Liverpool School and Eric’s. Probe became another hangout for Eric’s regulars such as Ian McCulloch, Julian Cope and Pete Wylie, the latter of whom would also work behind the counter at the shop.

With Eric’s’ world rocked by The Clash in May 1977 when the band’s White Riot tour arrived in town, McCulloch, Cope and Wylie would set down the seeds for their own musical endeavours by way of a fleeting and much mythologised collaboration as The Crucial Three. McCulloch and Cope found a home for their respective bands, Echo and the Bunnymen and The Teardrop Explodes, with Zoo, a record label founded by Drummond and Balfe, and run from a cheap office over the road from Probe. The fact that Zoo’s first release was by the recently split up Big in Japan was neither here nor there.

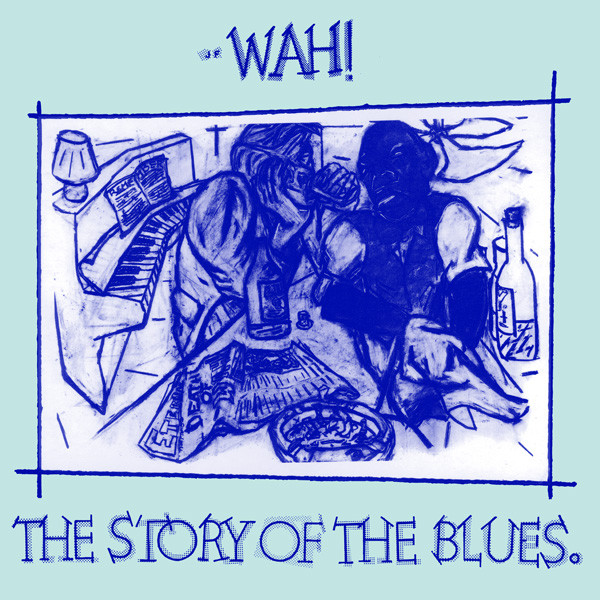

Eric’s came to an unfortunate end after three and a half years following a police raid during a Psychedelic Furs gig in March 1980, and the club was forced to close. By this time, Echo and the Bunnymen and The Teardrop Explodes were en route to major label glory, with Wylie’s band, Wah! following suit shortly afterwards.

Members of Big in Japan also went on to infiltrate the pop charts. Johnson and Rutherford led Frankie Goes to Hollywood to notoriety. Budgie became a key member of Siouxsie and the Banshees. Broudie produced a ton of great records before releasing his own as The Lightning Seeds. Balfe went on to form Food Records, signed a band who changed their name from Seymour to Blur, and who went on to write Country House about him.

As one half of The KLF with Jimmy Cauty, Drummond subverted the system on a grand scale, before the duo moved into art as The K-Foundation and gained notoriety for burning half of what Rishi Sunak is doling out for an imaginary Beatles museum.

Pete Burns, meanwhile, formed Dead or Alive, who went on to chart glory with You Spin Me Round (Like a Record), the first number one both for Burns and the Stock Aitken Waterman production team.

Jayne Casey’s post Big in Japan story is arguably the most fascinating of all. She became the voice of her new band, Pink Military, which morphed into Pink Industry, and ran her own Zulu record label. She later became head of performance at Liverpool contemporary arts centre, The Bluecoat, and went on to lead the media team for Liverpool superclub, Cream. When Liverpool was named as European Capital of Culture 2008, Casey was appointed co-creative director, and produced the opening event, persuading Ringo Starr to take part in an extravaganza featuring 800 other performers.

Casey later managed arts agency The A Foundation, which funded Liverpool Biennial, the UK’s largest festival of contemporary visual art, founded in 1998. She went on to co-found Baltic Creative, a trust responsible for developing the then run down Baltic Triangle district close to Albert Dock into a thriving independent cultural district fired with the spirit of Mathew Street of old.

Do it Clean

All these Eric’s era yarns of scallydelic DIY derring-do and more besides have been immortalised in numerous books penned by key players from the scene. First-hand accounts of the time appear in Julian Cope’s memoir, Head-On (1994), in writings by Bill Drummond in his book, 45 (2000), and elsewhere, and more recently in Echo and the Bunnymen guitarist Will Sergeant’s autobiography, Bunnyman (2021).

Extensive overviews also appear in Paul Du Noyer’s books, Liverpool: Wondrous Place (2002), and Deaf School – The Non-Stop Pop Art Punk Rock Party (2013). The title of Jaki Florek and Paul Whelan’s bumper sized volume, Liverpool Eric’s – all the best clubs are downstairs, everybody knows that (2009) remains the most evocative.

The point of retreading such a heroic dot-to-dot legacy is to illustrate how Rishi Sunak, Nadine Dorries’ two million quid’s worth of phony Beatlemania reveals a basic misunderstanding of where living culture comes from. Either that or else the Taxman and the Blue Meanie know exactly what they’re doing, and in their bid to ‘level up’, are throwing money to the gallery for a photo op and a chance to join hands for a rousing chorus of All You Need is Love.

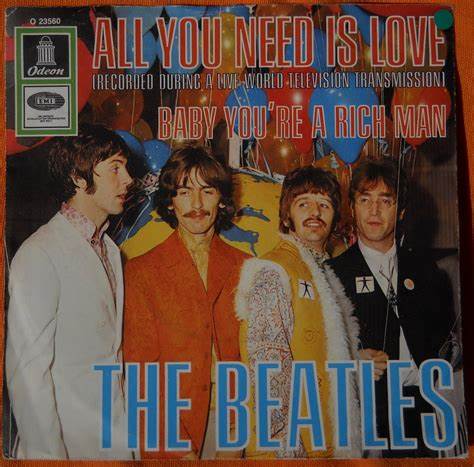

The Beatles sing-along epic, incidentally, was originally written for Our World, the first ever live global television broadcast, which took place in 1967. The group shared a bill with the likes of Maria Callas and Pablo Picasso, and attracted between 400 million and 700 million viewers in fourteen countries. They watched the biggest band in the world premiere an international anthem of peace and harmony that opened with a fanfare from the French national anthem.

Given the extent of what grew out of the unlegislated DIY arts village on and around Mathew Street, one might think it would have been invested in enough to thrive as what would these days be called a cultural quarter. As it was, the new Cavern was at the vanguard of a glossy 1980s makeover of the area that outpriced all the good stuff and forced assorted independent ventures to up sticks and move elsewhere. At one point there was a Mathew Street wine bar called The John Lennon Society, which required patrons to wear a tie.

All You Need is Cash

The Fab Four’s hippified subversion of the mainstream with All You Need is Love was a far cry from their days at the Cavern and their musical apprenticeship on the sleazy club circuit in Hamburg. As others have pointed out elsewhere, such a European adventure would be impossible now due to Brexit inspired red-tape and the assorted extra costs that are currently preventing today’s generation of musicians from touring abroad.

In the UK too, music scenes are being legislated out of existence, and if they are to survive require major government support. As Mark Davyd of Music Venue Trust pointed out on Twitter following Sunak’s Beatles museum announcement, £2 million could go some way to helping latter day home-grown versions of The Cavern survive.

Davyd calls Sunak’s proposal ‘a great example of the detachment from reality and life experiences of our politicians. On all sides of the debate.’

Davyd also highlights the smoke and mirrors nature of Sunak’s announcement.

‘Let’s start with the easiest bit:’ he writes. ‘It doesn’t build a Beatles museum. You read that correctly and you haven’t gone mad. The government just gave Liverpool £2 million to work out if it might build a Beatles museum. It doesn’t buy a single brick.

‘The Conservatives support a potential project with £2 million to plan it, because they want the political capital of ‘investing in the north’. Labour welcome the £2 million and start fancifully describing what it might achieve, because they want the credit of doing something.

‘Both say a Beatles museum will inspire young people into careers as musicians & deliver the creative skills of Lennon/McCartney,’ Davyd continued. ‘But John, Paul, George and Ringo didn’t learn their skills in a museum. They weren’t inspired to be the Beatles because of a plectrum in a display case.

‘Rock and Pop music, and the rich tapestry those generic terms might include, isn’t a semi-detached day out gawping at history in exhibitions. Stormzy didn’t start rapping because he saw an animatronic figure clutching a Rickenbacker bouncing up and down on two fake legs.

‘Liverpool has a vibrant and thrilling culture of creativity that you can already visit, feeling the visceral pulse of new music beating out of an under lit and wonky stage delivered by the next generation of great artists from the city. It’s infrastructure of grassroots music venues, the places that actually inspired and developed the Beatles, is massively under invested in, crippled by the Covid crisis, and in desperate need of support.’

Davyd understands this more than most. In 2014, he set up Music Venue Trust with Beverley Whitrick to help protect, secure and improve music venues in the UK. One of the main reasons for founding the organisation was to try and tackle the results of encroaching gentrification that left grassroots music venues vulnerable to noise complaints from new residential developments. MVT was instrumental in introducing the Agent of Change principle into law in England, Scotland and Wales. This puts grassroots music venues on an equal footing with residents when planning decisions are being considered.

One of MVT’s champions is former Beatle Paul McCartney, who in 2016 spoke out in support of the trust, saying that ‘If we don’t support live music at this level then the future of music in general is in danger’.

While McCartney’s views on the proposed third Beatles museum aren’t known, the fact that he talked about the future of music rather than its past is probably something for Rishi Sunak and Nadine Dorries to consider.

Regarding the future of music posited by McCartney, Davyd’s twitter thread offers up a set of aspirations infinitely more feasible than The Pool.

‘£2 million,’ he says, ‘would literally resolve almost all of the problems those existing venues face. Improved facilities, better lights, better sound, more support for diverse programmes.

‘£2 million. You could open three incredible, world class, new venues. Not plan to open them, or think about what they might do if you opened them. Actually open them. Three new spaces. An extra 700 events a year, catering for 2500 new acts, 8000 musicians, 4000 crew, 70 fte jobs and audiences of 190,000 people. Actually making and enjoying new music. Some of it with the potential to be as important to people, and to Liverpool, as The Beatles.

‘But the Conservatives and Labour both agree we shouldn’t do that’, Davyd writes. ‘They both think we should spend £2 million exploring whether we could capture a tiny part of the daily creativity of the city from 60 years ago in a photo or an artefact, pop it in a glass box and gawp at it. Because both apparently believe that will make young people stop watching TikTok and write Strawberry Fields Part 2. You know, like when John Lennon was inspired to take a degree in music production because he had a day out at the Glen Miller Gardens.

Davyd goes on to highlight the Conservative government’s fondness for high profile vanity projects that never materialise.

‘Time after time,’ he says, ‘big shiny projects, like garden bridges, floating airports and Beatles museums, trump sensible investment like making your local music venue accessible to all or just giving musicians a decent PA. Or even somewhere to play.

‘Headline grabbing, pointless nonsense that no one needs or wants and does precisely less than the sum of bugger all to support genuine creativity eating up real money that could make a real difference.

Davyd finishes his thread with a prediction.

‘The Beatles museum won’t ever be built,’ he writes. ‘If it is, it will fail to deliver a single thing on the list of grand ambitions that the politicians claim they want to build it for.’

Yesterday

Looking beyond Sunak’s Beatles museum proposal itself, the treatment of Liverpool by successive Conservative governments over the last half-century or so makes you wonder. The falsehoods propagated about the 1989 Hillsborough tragedy, which claimed the lives of 97 Liverpool football fans, have left their mark, while the courts have found those in charge on the day not guilty of any crime.

In 2004, The Spectator magazine, then edited by Boris Johnson, published an editorial following the murder of Liverpool born Ken Bigley in Iraq. The article talked of Liverpudlians who ‘see themselves whenever possible as victims, and resent their victim status; yet at the same time they wallow in it.’ The editorial went on to repeat some of the falsehoods about Hillsborough originally published in Rupert Murdoch owned tabloid, The Sun, which has long been boycotted in Liverpool.

With all this historical baggage, proposals for The Pool might look like so much circuses and bread on a par with the International Garden Festival that ran in Liverpool throughout the summer of 1984. This was initiated by then Environment Minister Michael Heseltine as a response to the riots that took place in the then run down Toxteth district of the city in July 1981.

Three decades after the riots, it was revealed in government files released under the thirty-year rule that at the time Thatcher’s Chancellor Sir Geoffrey Howe had urged her to adopt a policy of ‘managed decline’ towards Liverpool. This confirmed what many who lived in the city during that period had suspected for years.

Howe wrote to Thatcher of how ‘We do not want to find ourselves concentrating all the limited cash that may have to be made available into Liverpool and having nothing left for possibly more promising areas such as the West Midlands or, even, the North East.’

Howe went on to say how ‘It would be even more regrettable if some of the brighter ideas for renewing economic activity were to be sown only on relatively stony ground on the banks of the Mersey.

‘I cannot help feeling that the option of managed decline is one which we must not forget altogether. We must not expend all our limited resources in trying to make water flow uphill.’

Howe’s proposal came in the wake of Thatcher dispatching Heseltine to Liverpool as unofficial ‘minister for Merseyside’ following the riots. If Howe’s letter had been acted upon, Thatcher’s government would have actively destroyed a city that had stood up to its anti community, anti society, anti working class policies more than most.

Thatcher would soon be taking similarly ideologically driven action during the 1984/1985 Miners Strike. Even if she didn’t get Liverpool this time, the conflicts between her and the city’s left wing city council caused long-term damage on a grand scale.

In the meantime, Michael Heseltine had swung in to the city with a flourish, quickly setting up the Merseyside Development Corporation in 1981 to regenerate the city’s abandoned docklands. The Garden Festival was an early result of the MDC’s tenure, with Tate Liverpool opening in 1988 in a converted docklands warehouse space designed by architect James Stirling.

Meanwhile on Mathew Street, someone had finally realised they could make a few bob off The Beatles, and plans were drawn up at the end of 1981 to excavate the remains of the original Cavern. This was abandoned in 1982 due to damage caused by the demolition of the ground floor of the building housing the club a decade earlier.

In the end, the new Cavern was built a few feet away from the club’s original site, with a swanky high-end shopping mall called Cavern Walks on top. This new Cavern played host to tourists, as well as providing a much-needed venue for bands. Financial difficulties forced the club to close in 1989, before it reopened under new management in 1991, and has remained open since then. In 1999, Paul McCartney played a gig there to launch his new album. A film of the show was later released on DVD.

The reimagined Cavern is arguably the only Beatles museum Liverpool needs. While happy to embrace and exploit its legacy, more importantly, it provides a much needed place for living artists to play.

During the city’s European Capital of Culture year, one of the event’s featured shows was Eric’s The Musical. This new play by Mark Davies Markham celebrated Mathew Street’s other world-changing club shut down in its prime. The play was presented at the city’s Everyman Theatre, which in 1974 had premiered Willy Russell’s Beatles based breakout play, John, Paul, George, Ringo… and Bert. Numerous Beatles based shows have followed. Rather than ossifying Liverpool’s musical past, such artistic depictions of it bring it to life in a way that not only to shows where things have come from, but to point the way forward.

Whatever the perceived pros and cons regarding the long term worth of European Capital of Culture 2008, it nevertheless suggested the Mersey tide had turned, and that Liverpool was a city looking towards the future.

Talk About a Revolution?

Back in 2008, Jayne Casey talked in an interview with the Liverpool Echo about how ‘cities always really benefit from youth culture, but they seem to only be able to deal with it as a heritage issue. It’s the challenge of every city, not just Liverpool, to be able to deal with youth culture when it’s at the cutting edge.’

Casey also recognised the long term effects of grassroots culture in basement dives like The Cavern and Eric’s.

‘We start off life as rebels,’ Casey said in 2008, ‘and eventually become stakeholders’.

Eleven years later, Casey spoke in an extensive interview on the Baltic Triangle website of how her own artistic roots in Eric’s and Cream influenced her work with the trust. https://baltictriangle.co.uk/baltic-profiles-jayne-casey/

‘My backstory,’ Casey explained, ‘is that I’d been on Mathew Street in ’77, it was a derelict street, Eric’s opened, and people used to come down from London and then the developers moved in, so we moved over to the Cream area of town, which was again derelict. Then Cream opened and loads of people started coming in from out of town and the area re-developed again.

‘As the area was getting more popular, we tried to buy the building, but the man who owned tried to charge us ridiculous prices. Because we go into areas as artists, we set up our businesses, the area takes off because of our creativity but then the developers move in, and then you have to leave.

‘So, I’d gone through it in Matthew Street, so by the time we got to 2008 and the city centre had been given away for a quid, I made it my project to stop these things from happening.

‘I’ve built some fabulous things in this city which have either been destroyed or the areas have been taken off us by developers and I just really wanted to stop that. I was thinking ‘how do I make the artists the winners?’.

Casey talks in the interview of something she calls ‘the beauty of dereliction’. As she acquired neglected property, she began the Baltic Trust, and developed this in a very real sense of the word into a community of independent businesses that included club space, District.

‘The Baltic area is so experimental and so independent,’ Casey says. ‘This area gives people the chance to experiment, open up tiny little bars and cafes, maybe grow them, maybe not.

‘I was the lightning rod, but everything you see has been created by the people, the artists who’ve come in and made it what it is.’

Casey and Baltic Triangle’s initiative avoids the age-old cycle of spontaneous grassroots spaces being pounced upon by developers once an area is deemed ‘cool’.

‘For me,’ Casey said of the area in the 2019 interview, ‘when we were trying to put it all together, I was saying, I want somewhere where my people can live forever. Where my people in the future can find a home, and when I look around now that’s what it’s become’.

All of this grew from ideas born, not in the fossilised quietude of a museum, but from the noisy underground mess of a basement music venue almost half a century ago. The stripping of Liverpool’s much cherished world heritage status by UNESCO in July 2021, alas, has left such genuinely independent innovations at the mercy of developers once more.

UNESCO made their decision to delist the city following concerns over major developments of new buildings on the waterfront, and what they described as the ‘serious deterioration and irreversible loss’ to the historic value of its Victorian docks. UNESCO stated that as a result of the various high-end developments over the years, the waterfront had ‘deteriorated to the extent that it has lost characteristics’ that led to Liverpool being given world heritage status in 2004.

A proposed new Everton football stadium at Bramley-Moore dock, would ‘add to the ascertained threat of further deterioration and loss’ of the city’s historic value, UNESCO said. Presumably the proposed building of The Pool on the waterfront would potentially do similar.

Following UNESCO’s decision in July, Jayne Casey was reported as saying the announcement ‘felt like a depressing landmark in the city’s otherwise proud cultural history’.

“We’ve been aware for a long time that developers have got a lot of sway in the city,” Casey said. “The champagne will be flowing tonight for them because every little bit of land will now be built on.”

Casey also pointed out how a development boom in Liverpool had affected the city’s artistic life.

“Liverpool’s shifted from being a cultural city to one that’s just like everywhere else,” she said.

Casey’s views on proposals for The Pool aren’t known as yet, but whatever they are, Rishi Sunak and Nadine Dorries should probably listen to her hard. What looks like an attempt to Disnify Liverpool’s past glories suggests they are not so much believing in yesterday, but in some nostalgic fantasia of a past they never knew, and a swinging sixties that never really existed. This isn’t so much levelling up as London calling the shots as much as it ever did. As long as that is the case in Liverpool and elsewhere, yesterday will never be far away, while tomorrow never knows.

Livepools problem (along with many cities/towns in the North and Scotland) is that young people with ambition leave.

Londons calling…….always has done, but when you have a megacity of 10m in a small island of 70m what do you expect?

“The government just gave Liverpool £2 million to work out if it might build a Beatles museum. It doesn’t buy a single brick.”

Yes, this is something I noticed when trying to fundraise grants to help get local people’s ideas off the ground. Often, all they wanted was a workshop, hall or industrial unit where they could get on with their plans uninterrupted. This type of support was very difficult to come by.

However, ask for £5k or £10k to pay a consultant to do a “feasibility”/”benchmarking”/”mapping” study?…..”No problemo! Here’s your cash.”

Tell me about it, Wul!

When I worked for our association of local voluntary organisations, I spent many thousands of pounds writing business cases for proposals that amounted in most cases to a cost of only a few thousand pounds. Basically, the first work I had to do was raise enough money in so-called ‘seed-funding’ grants to continue to pay my own wages. It used to bother me that this money could be better used in directly funding the work that the association’s member organisations were missioned to do. But that was the way the jobbie splattered, how the system worked.

This is one of the reasons why the bulk of charitable investment goes to national voluntary organisations: they have greater fundraising capacity than smaller local voluntary groups, which gives the former a huge advantage over the latter in the competition for charitable investment in the work they do.

Two things, no, three.

Most of this “levelling up” money is going to constituencies with Conservative MP’s, and not to the areas that need it most.

Secondly, in Scotland, this money is heading directly to projects that are Union Jack branded, with the deliberate intention of undermining Holyrood.

Thirdly, Nadine Dorries wouldnae ken culture if it jumped up and bit her in the arse.

As is said here, there is no need at all for another Beatles’ museum. We have the music, including acres of demos, alternate takes and whatnot, a mountain of literature, films, videos and two museums already. Total waste of money. It will attract more tourists but I cannot see it having any impact on grass roots music, the place the group came from. Not sure about Liverpool so much but one of the places that so many bands came together was at art schools, where young people often went just to not have to get a shit job / live solely on the dole. But everything now is about the ‘return’, ticking all the funding boxes, writing gobbledygook to stand any chance of any money. It is all so crass – just allow an environment where young people have a bit of time and space to create without strings, even if just for a short time, and stuff will happen.

I lived in Liverpool for seven years in the 90s and the flat I moved into on Lark Lane was just being vacated by Allan Williams, the man who gave the Beatles away. He was nice enough but clearly had never gotten over it and seemed to have taken to drink ever since. I once sat in his ex-wife’s house on Grove Park and tinkered on the baby grand they had there. She looked at me and said John Lennon used to sit there and play that piano. It was quite a moment.