Power, Abuse and Truth in the Catholic Church in Scotland

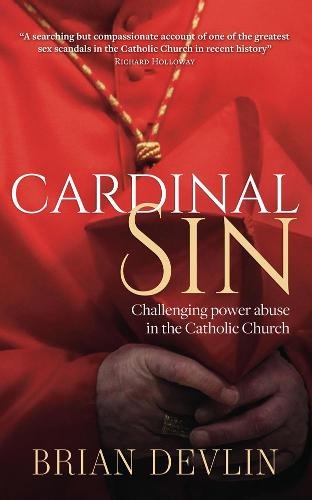

Cardinal Sin: Challenging power abuse in the Catholic Church, Brian Devlin, Columba Press 2021, £12.99.

This powerful book revisits the events surrounding the disgrace in 2013 of Keith O’Brien, former Cardinal Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh. At the time historian Tom Devine described this as the biggest crisis in Scottish history since the Reformation. Some may think they know the story; O’Brien’s sexual predation and the ham-fisted damage limitation at home and in Rome, but Cardinal Sin shows that this ‘biggest crisis’ is still unresolved.

One of the four whistle-blowers, Brian Devlin, waived anonymity to write this coherent account of O’Brien’s downfall. He explains why he, a former priest, and the three priests still in ministry, took the ‘nuclear option’ of approaching The Observer newspaper. A solution to the problem was already being shaped in Rome, after an earlier incident of impropriety had been reported by another priest. O’Brien would attend the conclave precipitated by the resignation of Benedict XVI, after which he would quietly disappear into retirement, possibly in Rome or more likely back in Scotland. That a sexually exploitative cardinal would be allowed to participate in the election of a new pope exhibits both a staggering naivete and hypocrisy.

The frustration among O’Brien’s victims is understandable because, even though their story had been brokered to the Vatican, they were now let down. It looked like O’Brien would walk into the sunset as a retired Cardinal and Archbishop-emeritus. The Congregation for Bishops eventually spoke with Devlin after, exasperated, he telephoned directly to the perfect, Cardinal Marc Ouellet. There was no alternative plan to deal with O’Brien and no redress for the victims. The media proved to be the only recourse. The scandal first reported by Catherine Devaney in The Observer is contextualised by Devlin’s book in two important ways.

The first is personal. Brian shares the catastrophic impact of O’Brien’s behaviour on his own life. It is of the utmost importance to hear the victim and Devlin bravely shares his abuse. Years later, and as a direct result, O’Brien’s appointment as Archbishop proved to be the catalyst for Brian’s resignation from ministry. How could he work with a Bishop who had violated his emotional and sexual boundaries?

After Cardinal Sin appeared, Devlin said in a subsequent interview that he looked up to O’Brien almost like God. I prepared for the priesthood at St Peters College in Glasgow, at the same time Brian Devlin trained in St Andrews College in Drygrange. I recognised what Brian described as the infantilising nature of our ‘formation’. Impressionable working-class young men, enthralled by the mystique of the clerical club, we looked up to these priests, teachers and role models, but already under their power. Many of us, I’m sure, in or out of ministry, have spent years realising the inherent flaw in the club, doing our best to unravel our de-formation.

The second context describes the scale of Keith O’Brien’s grooming and manipulation. Cliques and power games, the inappropriate sexual advances, the worse for happening during Confession. When that perpetrator becomes a Cardinal Archbishop, Metropolitan and president of the Scottish Bishops Conference, the potential damage could be catastrophic. A question the book leaves hanging in the air is, to what extent O’Brien’s damage still shapes the culture and governance of the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh. A delayed enquiry, an unpublished report, perpetuates the condescension of the People of God and hampers the re-building of trust. The gospel itself advises that only the truth can set us free.

In the last section of his book, Devlin tries to make sense of the disaster, articulating issues still unresolved for the Catholic Church in Scotland and beyond. Here are four.

The appointment of bishops is still conducted in an atmosphere of unhealthy secrecy. How can it be that, while O’Brien’s behaviour was known by some, whispered about by more, he still (like McCarrick in America) became a Bishop and Cardinal? Six of seven serving Scottish Catholic Bishops were appointed after 2013 and Glasgow awaits a new bishop. Have we learned anything from this disaster that influenced these post-O’Brien selections or future appointments?

The governance of his diocese was seriously compromised by O’Brien’s sexual behaviour, perhaps even blackmail. A labyrinthine network, worthy of the Renaissance, divided his priests and his diocese. Gay cliques mistreated priests and people alike, souring relationships and dividing the local church. The Vatican agency, entrusted with creating a culture of safeguarding, recently broadened its mandate to include the growing awareness that adults, too, can be victims of spiritual abuse and abuse of power, precisely as happened under Keith O’Brien.

And talking of safeguarding, we need to ask has this, too, been compromised? O’Brien vetoed a national audit of historical abuse cases; we can only speculate why. While Pope Francis has issued guidelines, calling to account bishops who do not report allegations, can we be sure no Archbishop can ever thwart an investigation of any priest, volunteer, or employee, however senior, close or protected?

Devlin is warm about Archbishop Scicluna, who the Vatican finally appointed to carry out a Visitation of the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh. While his report may have scorched the varnish on the Pope’s desk it never saw the light of day, even in redacted form. Cover-up is the enemy of truth and the trust of the people and priests of Edinburgh, perhaps even the whole of Scotland, is still compromised.

Since Cardinal Sin appeared two significant things have happened in the Catholic Church globally. The report from France on cases of historical sexual abuse cases has been staggering and shaming in its scale. It reveals a church still coming to terms with its past, marred by clerical and institutional dysfunction. Even more recently, Pope Francis has initiated a process of engagement and consultation to last two years, engaging the whole church in a journey towards a Synod for renewal, October 2023.

The first phase of this process is to happen at the local level of each diocesan community. Brian Devlin’s book bears on this synodal process, posing live questions for the Catholic Church in Scotland today. If we can’t speak the truth of past and present hurts, how can we renew the Church for tomorrow? Cardinal Sin reminds us that it is irresponsible to let this ‘greatest crisis’ go unresolved. What Tom Devine said the day this scandal broke is still true now; the people of the Catholic Church in Scotland deserve the truth – nothing less.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

How sad ,the church needs to weed out people who are in this for themselves, and should admit there Failing’s make s good priest shan’t to leave the Church as they can’t handle the shame ,and few taking up the priesthood and O’ Brien was Devil hiding in vestments

So, on the evidence, the Catholic Church is a homo-normative patriarchy? Not the only one, if so.

…how many other reports have “never seen the light of day.”

Hennessy’s 177 pg doc – sent to the CDF – outlining cases of abuse at the Comboni Missionary Order’s Mirfield Seminary.

CDF report on my abuse by the Comboni priest (still alive & protected in Italy) Fr. R. Nardo.

@Mark Murray, that would be the events covered in this article?

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/oct/19/sins-of-the-fathers-sexual-abuse-catholic-order

The evidence would also suggest that the Catholic Church is an extensive conspiracy to sexually abuse children and vulnerable young men. At least, the perception is that there is a dearth of non-victim whistleblowers. I am saddened that nobody they turned to seem to have supported the abused.

I wonder where the respect for priests comes from. I recently watched a production of Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Mandrake Root from around 1524, and the churchman is portrayed as corrupt and devious. There was an outpouring of violence against the Catholic clergy in the Spanish Civil War. Institutional abuse around the world, in Canadian indigenous residential schools, Irish nunneries, African missionaries and so forth must have been known at some level for many generations. I had not yet registered the scale of the French revelations. Perhaps some older characterisations have been written off as Protestant propaganda, although in many cases the pot seems to be calling the kettle black.

I can only wonder what horrors are buried in the Vatican archives. Are they protected by being in a quasi-state?

Though I am not likely either to buy or to read this book, since the broad outline of both the specific case and the general tsunami of sexual abuse in the Church is shamingly only too well known to mass-goers.

However I do most certainly congratulate both the author and the reviewer for their candid exposition of these vitally important issues.

One matter regarding the review does however trouble me, the failure to comment objectively on the role of the current Pope in these matters.

It beggars belief that the reviewer is not aware of the abject failure of ‘umble and merciful Pope Francis to do anything but mouth platitudes about zero tolerance, play to the media gallery and invariably wheel out his personal spray can of mercy for clerical sex abusers.

Whilst the separation of Scotland from England & Wales in Vatican accounting means that Westminster is as foreign as Buenos Aires or Santiago de Chile for the author and the reviewer, sociological reality dictates that the very recent calculated and egregious slap in the face bestowed by Pope Francis on all survivors of clerical abuse when he high handedly reinstated Cardinal Nichols in London, after his age related retirement, on virtually the same day that the government inquiry into abuse in the Catholic Church with its coruscating comments on the cardinal’s manifest inadequacies in safeguarding the vulnerable was published is very well known to both of them.

The list of wholly inadequate reactions from Pope Francis is long and, both for him and for Catholics, shaming:

Bishop Borras in Chile where the Pope’s defence of the bishop when he visited the country was so outrageous that he was virtually hounded out of the country. Cardinal O’Malley of Boston wasindeed forced to publicly contradict the Pope. (For which he paid dearly when the Pope tried to freeze him out of the next synod he was due to be involved in.)

Cardinal McCarrick in the USA, where Francis chose to ignore the wholly inadequate sanctions placed on McCarrick by his predecessor Benedict XVI and gave him plumb jobs as a personal diplomatic emissary both to China and to Cuba.

Bishop Zanchetta, a long time friend and collaborator of Francis from 2000 to 2013 in Argentina, who was included in the Pope’s first list of bishops in late spring 2013 and who has been shamelessly protected by Pope Francis since his sudden resignation from the Diocese of Oran in Argentina. The fact that Zanchetta has been arraigned on 2 accounts of sexual abuse of seminarians has not in any way prevented Francis from inviting him to take up a sinecure post in the Vatican Bank, inviting him to sleep under the same roof in Sta Marta ‘pensione’ and indeed from sending a priest-lawyer from Spain to the court in Salta to help Zanchetta with his judicial problems.

In his final paragraphs, the reviewer speaks positively of the fruits he expects from the upcoming Synod of Synods (sic). Given Pope Francis’s record of cynical manipulation of previous synods where he has been happy to write the conclusions before summoning the participants, I am amazed at any such residual faith in the pontificate of Papa Bergoglio.

Not really relevant to the important topic which this book addresses, but there was an actual “Cardinal Sin”, who was the Archbishop of Manila in the Phillippines. Accounts and reports present him as a decent and courageous person who stood up against people like President Marcos and his clique.