Scotland 1979: Time, Crime and Telling Stories of the Past

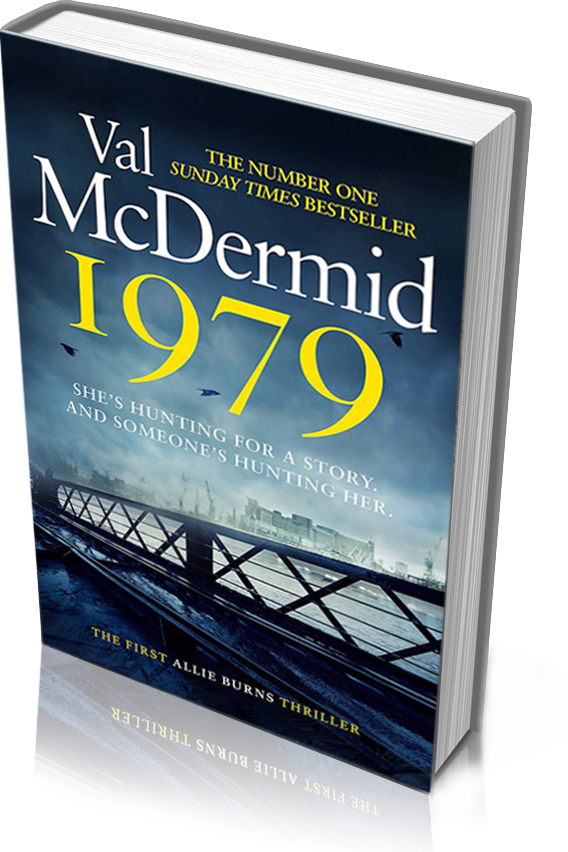

1979, By Val McDermid, Hachette, £20.

Reading Val McDermid’s new novel 1979, a line from L.P Hartley’s ‘The Go-Between’ kept coming back to me: ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there’.

That line may be a cliché, but it neatly sums up this novel’s central concerns. In 1979, the first of a series of five novels featuring journalist Allie Burns, McDermid invites us to walk again the streets of that foreign country. It turns out to be an awkward visit home.

And 1979 doesn’t feel very far away. I go there often. Surely nothing has changed in any fundamental way. And then this novel puts my eye to the wrong end of the telescope and the gulf becomes clear. The social, political and cultural landscapes have changed and changed utterly – McDermid is an anthropologist describing a lost tribe.

The autobiographical elements of the novel are obvious. We meet Alison (Allie) Burns, a 23-year-old journalist working on The Clarion, a Glasgow newspaper. Burns grew up in East Wemyss, a village in Fife well-known to Kirkcaldy-born McDermid; Burns graduated from Cambridge, McDermid from Oxford; both cut their journalistic teeth on newspapers in England before working in Glasgow.

1979, McDermid’s 35th novel, is arguably more concerned with time than it is with crime. Sure, there is skulduggery afoot, but this operates more as a social document, a window on a time so different from our own it seems scarcely believable, than as a conventional crime thriller. The atmosphere is not particularly dark – a lighter, almost comic tone is set in paragraph one with the mention of ‘Showaddywaddy’s Greatest Hits.’ The setting is fully realised, the main characters are, as you would expect, convincingly drawn, but the plot itself can feel slightly unbelievable at points. The minor characters are a bit sketchy and stereotypical. For example, journalists are all (bar one) unreconstructed men, alcoholics who spend more time at the bar than at a desk.

But Val McDermid is a phenomenally successful writer of crime fiction, and if anyone can write social and cultural history into a crime story, then she can, Actually, two crime stories, dealt with sequentially: the first is a tax evasion scandal, uncovered by Burns and the closest thing she can find to a kindred spirit, a young journalist called Danny Sullivan; the second, and the less believable of the two, a plan by three remarkably naïve-even-by-1979 standards young men to buy weapons from the IRA, weapons they hope will, as one puts it , ‘blow the bloody doors off’ the struggle for Scottish independence.

This dual plot made the novel feel at points like two separate stories tacked together, and I found myself waiting for the second shoe to drop. The plot is really there to give the characters something to do while the setting and its effect on those characters is drawn for us. Consequently, it never feels that tense, with not enough of the expected ‘heart pounding’ drama.

Surprisingly, the dialogue can occasionally strike a dissonant note – at one point, Rona Dunsyre, Rogano-dining West End Women’s Section journalist, describes something as ‘pure dead brilliant‘. I searched long and hard, but ironic intention found I none. Burns says at one point, ”I’m from Fife (‘Fae Fife’ surely – Ed.) – Gallus is my middle name’. Is it, aye? When Sullivan makes initial contact with the three would-be bombers, literally his first words after hello are, ‘I was told this was the place to find men who were really serious’.

Now, I’m no expert on the infiltration of terrorist groups, and these three chancers are absolute beginners at the terrorism, but starting the conversation like that would, I suspect, lead to even their novice eyebrows being raised. Fragments like these render the willing suspension of disbelief a big ask.

The Scotland of 1979 is not pretty. A grim Gang of Three – Sexism, Homophobia and Sectarianism – dominates the scene. It is painful to remember how it was. Perhaps a few snaps from my own family album will remind us of how things were.

Here’s one. As a baby in one of the few Catholic families in 1960s Bridgeton, I was introduced to sectarianism one night when my father answered the door to our single end, holding me in his arms. The man on the landing casually punched him and we fell together. Later, growing up in Cumnock, where we moved in 1967, I was called Fenian so often I almost came to believe it was my middle name.

In 1977 I started an English degree, at a time when female students were barred from the Beer Bar at the Glasgow University Union. In this one several young women are being huckled collar and arse, and dumped on the pavement outside.

Women and Catholics may have been fair game in the Scotland of 1979, but being gay placed you firmly in the crosshairs. In the Scotland of 1979, homosexuality was very much still in the closet, at least if it knew what was good for it. In 1982 my flatmates and I allowed a homeless old alcoholic casualty to sleep on our floor for a few nights. He spent most of his time drinking BelAir hair lacquer in our toilet, before disappearing with £30 to replenish his lacquer stash. Two of Cranstonhill’s Finest began their investigation by asking me if I was a poof. More telling than their question was my response. No, I said. I’m not. Ten years later, a gay man died after being set on fire in an industrial estate in Cumnock.

This gang stalks every page of this novel, most obviously in the overwhelmingly male staff at The Clarion. Cambridge graduate Burns is routinely dismissed as a ‘wee lassie’, and has to fight to gain admission to the male drinking and snooker club that is The Clarion.

She comes in handy when an occasional feel-good ‘miracle baby’ story needs to be covered, and her only female colleague writes about fashion from a tiny office with barely room for a desk. She has to let Sullivan take over an undercover role because she is told, and she agrees, that a woman will not be taken seriously. A murder victim is described by a reporter as ‘a decent guy, for a Catholic’. A gay character is referred to as a ‘wee shirt lifter’ by a senior figure at the paper, another is casually described as ‘looking like a wee poof’. And it is not only the language that is violent. Another gay character flees to Manchester, where at least, sex with a man will not land him in jail. 1979 is a chilling reminder of how things used to be. Of how we used to be.

From 2021, the significance of 1979 is pretty clear. Presumably McDermid chose it because it was a genuine watershed. That May, Thatcher’s monetarist tanks rolled into Downing St, marking, if not the end of the innocence, at least its death agonies. The Devolution Referendum two months previously was already old news. Scotland had spoken, sort of, those who chose not to vote most loudly of all. It would be nearly twenty years before we got the chance to speak again.

1979 marked the tentative beginning of the end for the Scotland of my parents’ generation, a Second World War-experienced generation, for whom separating from our English comrades-in-arms felt like a betrayal. Even though that generation is inexorably dying off, those of us committed to Scottish independence would do well to remember and respect these feelings. Smug pronouncements about butchers’ aprons merely serve to alienate those we really need to incorporate. We should tread lightly. For we tread on their dreams.

The real strength of McDermid’s novel lies in its unflinching depiction of a past we would probably rather keep locked in our national attic. Burns and Sullivan are engaging protagonists, and we sympathise with them as they battle the Neanderthal attitudes of colleagues and police. Let’s see them as harbingers of the new Scotland that has been evolving since 1979– diverse, inclusive, confident – and, what the hell? Maybe even gallus.

Who knows where that story will end?

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

1979 was really the start of the continuously widening political split between Scotland and England. We had the first referendum on devolution, which YES won, but, because of LABOUR chicanery the result was set aside because 40% of the electorate had not voted for it. This led to the SNP tabling a voter of no confidence in the Callaghan Government, but Mrs Thatcher, sniffing victory put down her own motion of no confidence and since the Tories were the official opposition, it was their motion that was debated and won by 1 vote. Labour, of course blamed the SNP, but Mr Callaghan was quite clear it was his own party which had caused the problem.

In the election which followed, against the trend in England and Wales, Scotland voted heavily for Labour (reducing the SNP to a few seats) and Mrs Thatcher’s ‘man in Scotland’ Mr Teddy Taylor was unseated. During the 1980s, the Tory representation in Scotland continually fell, until in the early 1990s, Scotland was a Tory-free zone.

They only made a comeback due to the Scottish Assembly and proportional representation, both of which they opposed. Although, Labour until 2007 was still the main party in Scotland, it was clear that even with Labour in power and, to be fair, being fairly redistributive, Scotland was becoming increasingly disenchanted by Blair and ‘new’ Labour. The invasion of Iraq and the huge demonstration against it in Glasgow, indicated a clear difference with the jingoism of the media down south. This was an echo of the reaction in Scotland during the Falklands War of 1982.

In 2007, when the SNP became the largest party, many in Scotland felt, ‘maybe we really can rule ourselves’. Scottish Labour began to die of its own sour oppositionist bitterness and its hatred of the people of Scotland for denying them Labour its ‘entitlement.

In England, even with the most corrupt and incompetent Government in my lifetime, Labour is far behind in Westminster seats and has no story to tell the people of England. In Wales, Labour has an agreement with PC and it is no ‘crime’ to advocate independence. Labour has never organised in Northern Ireland and, today, a Labour spokesperson said that in the event of a vote on Irish reunification, Labour would be neutral.

Meanwhile, Scottish Labour nurses its hatred and contempt for the people of Scotland for rejecting them and continues to denigrate Scotland, its culture and its people. There are more elected Tories in Scotland than Labour. The last time this happened was 1955.

I remember 1979 as the year Jean-François Lyotard published La Condition postmoderne: Rapport sur le savoir and the world became incredulous. We could no longer agree on what, if anything, was real, and the metanarratives of modernity/capitalism (‘Truth’) began to disintegrate into an abundance of micronarratives (‘truths’); that is, into a multiplicity of innumerable and incommensurable knowledge communities. It was the year that we started to let go of unity and solidarity as social virtues and become alert instead to difference, diversity, and the radical incompatibility of our respective aspirations, beliefs, and desires in society. It was the year we entered an epoch of revolution that is changing the world utterly.

Having lived in Glasgow in 1979, I do not recognize the picture John McIntosh paints. The idea that ‘Women and Catholics were fair game’ is simply not credible. The position for women had been massively improved by the reforms of the Labour government (1964-70). Being banned from the Glasgow University Union Beer Bar was more a blessing than a hardship.

Similarly, I find it hard to believe that he was one of the few Catholic families in Bridgeton. Catholics made up at least 20% of the population of working class Glasgow – right across the city. By 1979, the endemic employment discrimination was easing as Catholics benefitted from the massive expansion in secondary and higher education.

He writes that it is ‘painful to remember how it was’. In reality, it was better than today in some respects; there were no foodbanks; the idea of police in schools would have been unthinkable – today there are police officers in 25 of Glasgow’s 30 secondaries; there was an industrial economy which, though weakening, still gave skilled work to thousands of employees.

Glasgow may be diverse and inclusive. I see little evidence of it being confident. There is far more evidence of demoralization. This is visible not just in the left behind areas such as Govan but in the faces of ordinary people in the city centre.

I tend to agree. There were prejudices of all kinds but people were resisting them, challenging them (with some success) and in ordinary daily life most people in working class Glasgow were respectful and caring. It was a different world in that it was easier to find a job and Social Security was slightly more generous, but, sexism, sectarianism and prejudice have not gone away: they are alive and tweeting every second of every day.