William McIlvanney, Ian Rankin and 1970s Scotland

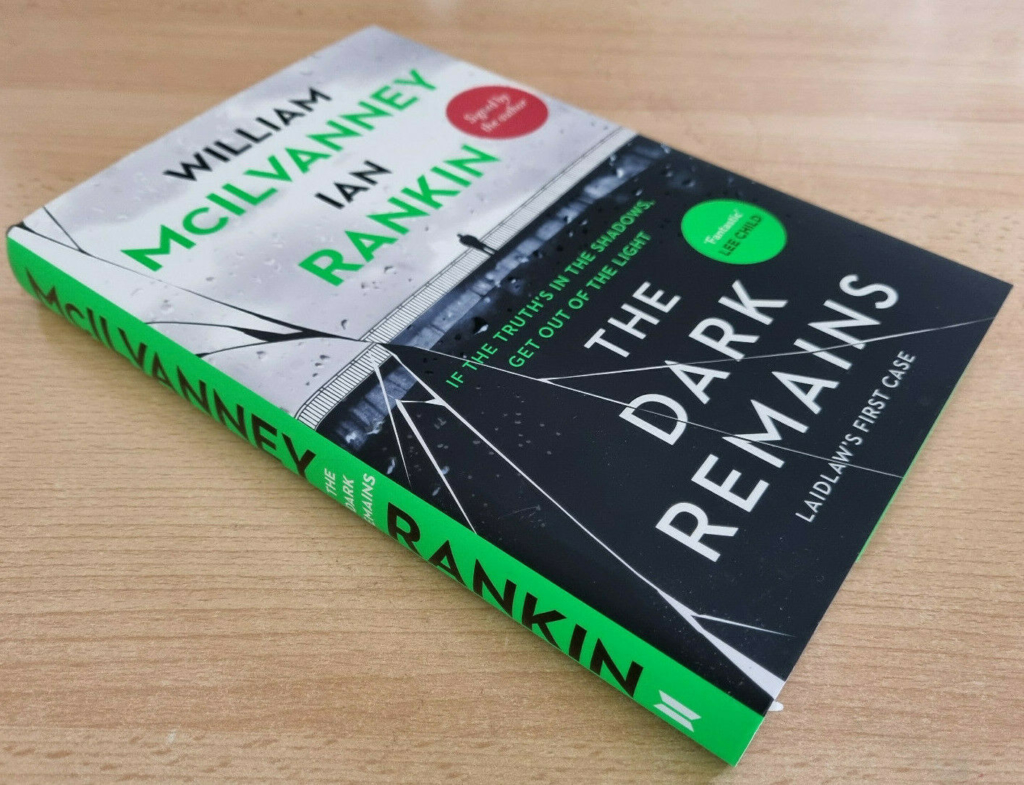

The Dark Remains, William McIlvanney and Ian Rankin, Canongate, £20.

The Dark Remains, William McIlvanney and Ian Rankin, Canongate, £20.

William McIlvanney is generally accepted as the father of Tartan Noir, so it is perhaps surprising to remember the sniffiness with which his initial foray into crime fiction was greeted in some quarters. When ‘Laidlaw’ was published in 1977, McIlvanney was already a successful ‘literary’ novelist, winning the Whitbread Prize in 1975 for ‘Docherty’, and a Great Scottish Novel seemed only a matter of time. Why on earth would he venture into genre fiction?

‘Laidlaw’, McIlvanney’s debut in the genre, introduced the world to DI Jack Laidlaw, ‘a man who happens to be a cop’, and was followed six years later by ‘The Papers of Tony Veitch’, the trilogy being completed in 1991 with the publication of ‘Strange Loyalties’. And, we assumed, that was that, especially after McIlvanney died in 2015.

Haud yer horses a wee minute but, as Sherlock Holmes might not have said. Assume nothing, Watson. After his death, McIlvanney’s wife discovered a fourth, unfinished, ‘Laidlaw’ novel among his possessions. His publishers approached Ian Rankin with the suggestion that he complete the novel, which he duly did. It’s never clear how much or how little of ‘The Dark Remains’ Rankin was given to work with. It’s certainly impossible to discern a particular moment when the pen was passed.

This brand new ‘Laidlaw’ novel, ‘The Dark Remains’, is a prequel, set in 1972, when Jack was still a humble Detective Constable. Glasgow crime boss Cam Colvin’s lawyer, Bobby Carter, is found stabbed to death behind a pub run by Colvin’s rival John Rhodes, and Laidlaw has to find the killer before the city erupts in a cycle of tit for tat killings.

Exciting as this undoubtedly is to fans of the original trilogy, the novel seems to me to be, in one regard, a bit of a missed opportunity. I wanted a real origin story, a kind of ‘how Laidlaw became’ thing (people love that, which is why Marvel keep making that Spiderman movie).

Some early footage of the young detective learning his trade, finding his feet and making rookie errors would have been fascinating. But the Laidlaw we meet here is already fully formed, down to the philosophy books in his desk drawer ‘like caches of alcohol’ (next to the caches of alcohol); the love of literature (on one page he manages to talk to his bemused colleague DS Lilley about John Updike and W.H. Auden); the continual boozing; the disappointing and loveless marriage, and the associated infidelities with more understanding women who go weak at the knees over his gruff charms.

Of course, in 1972, fictional women tended to be support players, and there are few female characters in the novel, at least compared to the large cast of men we encounter. Arguably that reflects 1970’s Glasgow gangland, but Ena, Jack’s wife, and Margaret, Lilley’s wife, are interchangeable as Wife 1 and Wife 2. They might as well be referred to as ‘er in doors’.

The novel’s time frames do seem a bit confusing though. At the beginning Laidlaw is apparently ‘in his late ’30s’. with the blurb stating that ‘The Dark Remains’ is Laidlaw’s ‘first case’, while in chapter 2 his boss, Commander Frederick, refers to him as the ‘new boy’.

The Jack Laidlaw presented in this novel, may be many things, but a boy he is not. He is already that hard-bitten and world-weary philosopher-cum-bevvy merchant-cum-hard bastard, fronting up equally effortlessly to Glasgow gang bosses and his own bosses. Sure-footed, cool and professionally untouchable, he variously ignores, insults and humiliates his superiors with apparent impunity. He is that classic stock character, the ‘maverick who gets results’. He combines the cocksure swagger of a Dirty Harry, the ability to get inside the bad guy’s head of a Will Graham, the unexpected neuro-divergent insights of a Saga Noren, and the moral clarity of an Elliot Ness.

Alternatively he is McBain in ‘The Simpsons’, who responds to his boss’s order to ‘go by the book’ by drawing his gun and shooting a hole through said book. Laidlaw never goes quite that far, but he makes clear his utter contempt for his superior, DI Ernie Milligan, whom he believes to be an incompetent moron, promoted for his Masonic connections and has little interest in promotion.

Reading the first two ‘Laidlaw’ novels in my early twenties, I was immediately smitten by the character. Here was a new thing. It was immediately obvious that McIlvanney was interested in going beyond the conventions of the genre, in exploring themes not typically associated with crime fiction.

Jack Laidlaw was intelligent, compassionate and possessed of a liberal education, qualities that were not always on display in some of his non-fiction counterparts. His conviction that there was no simplistic divide between goodies and baddies, that circumstances and environment largely determined whether you became a respectable pillar of society, or a wrong ‘un, felt pleasingly progressive.

As shotgun-toting drug dealer–robbing Omar made clear in ‘The Wire’, there’s more than criminals make money from crime. Who can forget that famous courtroom moment when he admitted to the prosecution that yes, he used a shotgun, but pointed out that the lawyer himself used a briefcase to much the same end – they were both living off the same game. Laidlaw would have loved that.

Such a progressive take on criminology may be taken for granted now, but that is a relatively modern phenomenon. McIlvanney, a life-long socialist and long-time Labour supporter, was ahead of his time in creating a character intelligent enough to see the common humanity of his criminals, and politically aware enough to understand the structural reasons why some become police and some become thieves.

Glasgow was always a tangible presence in the ‘Laidlaw’ trilogy, and McIlvanney was captivated by the city. He captured its flavour like few before or since. Squalor, violence, dirt, hatred, and despair on one hand; beauty, love, humour, energy, and defiance on the other. The city does appear in ‘The Dark Remains’, just not in such a prominent role – maybe because Rankin is from the other place. Laidlaw refers to ‘the infinite jigsaw that makes Glasgow the Second City of the Empire’.

When he tells an old man at a bus stop that ‘We’re all actors in this town’, he captured something important about the city. Partial to an audience, Glaswegians do not need much encouragement to get up and perform. Maybe endemic low self-esteem has to be bolstered by something, and, like neglected children, we seem to crave attention. McIlvanney has always been aware of that tendency. In his short story ‘Performance’, he described a guy walking into a bar and ‘accidentally’ showing off a big roll of bank notes to the awe-struck punters. Only when he is back on the street is it revealed that the roll is actually cut up newspaper wrapped in a single fiver. We may be poor, we say, but we can still put on a show.

One criticism sometimes levelled at McIlvanney is a tendency to over-write, to have the ‘veins bulging in his biro’ as Seamus Heaney wrote. He finds it hard to resist showing off his ear for an extended metaphor, and sometimes seems to be striving after the snap, crackle and pop of Raymond Chandler: ‘I’m an occasional drinker, the kind of guy who goes out for a beer and wakes up in Singapore with a full beard’. But this can get a bit wearing unless the lines are real zingers, and sometimes, they are not: ‘Milligan wasn’t so much barking up the wrong tree as looking for a tree in the widest of oceans’.

When such heavily stylised lines are put in the mouths of characters, the fictional world can seem a long way from the real one. Would a Glasgow detective really say to a group of hoodlums, ‘You’re barely specks of dust floating over a buckled tin ashtray’. It’s just a bit too close to Jonathan Watson doing McIlvanney’s deliberate and portentous speaking voice in ‘Only an Excuse’.

Such criticism, however, feels churlish now. The publication of ‘The Dark Remains’ is a Scottish cultural event, because McIlvanney was a genuine trailblazer. He invented a distinctively Scottish crime fiction, and many modern crime writers, Scottish and otherwise, recognise that.

His ‘Laidlaw’ novels are ambitious, and Laidlaw remains a compelling figure. He is the kind of cop we want to believe is still out there, fighting against the corrupt and self-serving cynics we seem to hear about so often. He upholds the law, but he knows that is not enough. He knows that ‘the law is what we have when we can’t have justice’.

As 2021 ends, our faith in the possibility of justice is being sorely tested, as Home Secretaries and Prime Ministers refuse to lift their eyes from the letter of the immigration laws to look at the mothers and children drowning in the Channel. McIlvanney’s personal commitment to justice – in the workplace, in the country and in the world – gave birth to Laidlaw and for that we should be grateful.

At points McIlvanney apparently believed himself forgotten. In his poem ‘Grandmother’, he regrets failing to see the strong fighter his grandmother had been. He offers her his poem, as ‘wreath, gift, true apology’. In ‘The Dark Remains’, Ian Rankin has offered the same to McIlvanney himself.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by donating today.

One thing I liked is the back stories. “Tony Veitch” opens with Mickey Ballater arriving in Glasgow – we don’t know who he is or where he’s coming back to Glasgow FROM, but the other characters do (cf. John Rhodes’ comment “Who needs to re-import sewage?”) – but this book fills it all in, and something of the pre-“Laidlaw” histories of other characters too. And it’s a good story, though the basic idea (the murder of one of Cam Colvin’s associates threatening to bring about a full gang war between him and John Rhodes) is very like that of “Tony Veitch”. BUT – in the McIlvanney books the characters talk Glesga demotic – here they’ve all had elocution lessons. With the result that some of them – John Rhodes in particular – come across as pale shadows of their former selves. That is a MAJOR loss. Re-reading “Laidlaw” and “Tony Veitch” to refresh my memory, it just hit me how major. You might argue that Rankin couldn’t hit the real parliamo Glasgow if he tried, and so it’s just as well he didn’t try; but I think the loss is just too great.

“Oh, the banter!”

Liked the book, never saw the end coming