Scottish Education Examined – how the SNP is putting politics before pupils

Last summer, the second of the coronavirus pandemic, Scotland’s national exam diet was cancelled. The same thing had happened in 2020 but the circumstances, and the official response, were different. So now, with the third Covid-era exam period looming over the horizon, how are things looking for students and their teachers?

In March 2020, the emergence of Covid led to schools being physically closed (along with most of the rest of society) as we were all told to stay at home. With exams impossible, students in S4-6 had their grades assigned by teachers based on the work they had already completed up to that point.

Of course, we all remember the scandal that followed: both the SQA and the SNP government tried imposing a discriminatory algorithm that would keep grades in line with previous years, a process which (inevitably) targeted schools from the poorest areas and punished pupils for their postcodes. After trying to defend the indefensible for a few days the government backed down, John Swinney performed an apology for the cameras, and the algorithm was removed.

Last year (2020-2021) was a different story. Initially exams were supposed to be going ahead, even though those of us involved in delivering courses knew that this was never likely to be possible, so we started the academic year without knowing how we would end it and unable to be straight with students about how they would be assessed. It was an unforgivable failure caused by a government putting wishful thinking and its own political needs ahead of the needs of pupils. And so, when exams were eventually cancelled, it caused chaos. There would be no algorithms to keep the poor in their place, but teachers still weren’t trusted to do their jobs: instead, a system of ‘demonstrated attainment’ was put in place, the result of which was young people being ground through weeks, even months, of seemingly endless assessments in the pursuit of perfect paperwork.

In both cases the situation was a million miles from ideal. The workload for teachers was astronomical, while the pressure placed on students in 2020-2021 should be a source of lasting shame for those in charge. But it’s notable that the biggest problems were caused not by schools, or even by the pandemic, but by politicians and their officials.

Which brings us to the current academic year. It began much as the previous one had done – with the Scottish Government telling us that exams were going to go ahead. Surely, though, the same mistakes wouldn’t be repeated? Surely lessons would have been learned from the preceding eighteen months? You’d certainly like to hope so, wouldn’t you…

At that time, I tried to get more details from the government using Freedom of Information legislation. Here’s what I asked:

The Scottish Government has today confirmed that exams will take place in 2022 (if safe to do so) – https://www.gov.scot/news/national-qualifications-2022/

- Does the government have any definition or set of conditions that will determine whether it is “safe to do so”? If so, please release this information. If not, please confirm that it does not exist.

- What triggers have been set that would lead to the initiation of one of the contingency measures listed in the press release. Please either release this information or confirm that it does not exist.

- What specific checkpoints have been set to determine when decisions about 2022 exams will be made? Please either release this information or confirm that it does not exist.

When the response arrived it was…well…see for yourself:

The only hard detail that seemed to exist was a final date by which the government would have definitely made a decision. Maybe October, which was the month in which National 5 exams had been cancelled the year before? Or December, which was when the Highers and Advanced Highers had also been scrapped? Maybe even January as schools returned from the Christmas and New year break?

Nope.

The Scottish Government had in fact given itself a deadline of the end of March 2022 to decide if exams would go ahead just weeks later.

The term ‘significant disruption’ makes an appearance (more on that later) because it turns out that the government pledged that ‘further significant disruption’ would trigger ‘support measures…to help reduce pre-exam stress’. That threshold has certainly been reached since this response was issued to me (at the end of October 2021, more than a month late) and yet those support measures haven’t materialised.

And as everyone (including the Scottish Government) knows, the question of whether or not exams can go ahead is not simply a matter of whether “physical gatherings are restricted” at exam time.

I’d love to tell you that I was amazed by all this, and the incompetence underlying it, but I’ve been at this for a while now and it would simply be a lie.

So once again, we began the year without knowing how our students would be assessed. Once again, the government was content to bury its head in the sand. Once again, what plans were made were founded on wishful thinking and political advantage. Once again, the Scottish Government and the SQA failed young people.

And they are continuing to fail them even now. Responding to a story in a recent edition of The Herald, the SQA offered the following information about their plans for 2022 exams:

“As schools return, if there is significantly more disruption across the country than that experienced last year then we will take further steps to help learners by providing support for exam revision where possible.

If that happens it is important that information is provided at the right time to support revision. Providing this advice too far in advance may have the negative consequence of narrowing the teaching of courses, which would be detrimental to learners’ knowledge and understanding and to the next steps in their learning.”

There are a few things to note here. Firstly, the SQA seems keen to keep discussions about cancelling exams firmly off the table. Instead, their focus is restricted to the possibility of ‘providing support for exam revision’, which is code for telling schools which topics are going to come up in advance. It’s an obviously ridiculous idea of the sort that only seems sensible when you are, in fact, completely lost.

It’s also worth asking why there needs to be ‘significantly more disruption across the country than experienced last year’. The SQA – and by extension the government – are saying that things need to be worse than last year to convince them to take less action than they did back then. But why should this year’s cohort need to have had it much worse before they are entitled to far less support? It doesn’t make any sense if you are concentrating on fairness for young people – but it’s perfectly rational if what you’re really trying to do is rig the game against them.

Remember, last year’s exam diet was not cancelled because of lockdown and home learning from January onwards – it had already been scrapped before schools broke up for Christmas. It would be wildly dishonest for anyone to claim, for example, that the lack of a period of remote learning this year means that exams should go ahead, but would anyone be surprised to see precisely that argument in an SQA release or from a member of the government?

For the events of early 2021 to have had anything to do with cancelling last year’s exams the government would have had to have known that it was going to implement a lockdown weeks before the public were told. If that’s the case then I think people would want to know, but if it is not the case then decisions about this year’s exam diet need to be made on a like-for-like basis: the situation needs to be compared not to this time last year, or to any normal year, but rather to the period of September – December 2020.

This sort of consistency may be inconvenient for the government and the SQA but, if young people really are the priority, it’s also the very least that they should be able to expect.

They should also be able to expect a clear definition of ‘significantly more disruption’. A variation of the phrase has been getting thrown around for months (remember that FOI response from October last year) but, despite the massive challenges affecting schools, nothing has been done. So what are the metrics? Who is doing the measuring? What sort of data will trigger a decision, and who makes the call? I decided that I would try to find out.

I got in touch with both the SQA and Scottish Government and asked them the following question:

In response to a story in the Herald about disruption to schooling and the possible impact on exams, the SQA has provided the following comment:

“As schools return, if there is significantly more disruption across the country than that experienced last year then we will take further steps to help learners by providing support for exam revision where possible.”

Could you please confirm how you are measuring the disruption to schools, and what will trigger a judgment that there is “significantly more disruption” than last year? How would you draw the line between there being more disruption and ‘significantly’ more disruption, and what are the actual metrics for that disruption?

(I also asked the Scottish Government the following additional question: Could you also confirm whether the option of cancelling exams and switching to teacher judgement has now been abandoned? The SQA comment suggests that only ‘support for exam revision’ is being considered, which feels like something that needs clarified?)

The responses were not reassuring.

An SQA spokesperson:

“The Covid-19 Education Recovery Group is closely monitoring levels of learner and teacher absences, and school closures, and SQA will be guided by these in deciding whether to provide learners with additional support for exam revision. It is important to remember that the significant modifications already made to courses this year are designed to address the ongoing disruption to learning and teaching.”

A Scottish Government spokesperson:

“We will do everything we can to keep schools safely open and minimise disruption to learning. The plan continues to be for exams to take place in 2022, although we are closely monitoring COVID developments.

“If there is significant further disruption across the country, learners will be given additional support to help them prepare for exams. The decision on whether to move to this contingency will be taken by the SQA in consultation with the Scottish Government, the COVID-19 Education Recovery Group, the National Qualifications 2022 Group and other partners.

“A range of factors, including staff and pupil absence rates, will be considered.

“If public health conditions do not allow for an exam diet to take place, awards will be made on teachers’ judgements based on normal in-year assessment.”

So, what is the difference between disruption and ‘significant disruption’? What are the trigger points at which a decision will be made? It’s not even clear that either the SQA or the Scottish Government know the answers to those questions, but that can only be because they do not want to know the answers or (far more likely) because the answers simply do not exist.

The actual cancellation of exams will only be considered, it seems, if it looks likely to be unsafe to hold such gatherings in April/May, while ‘significant further disruption’ before then will only trigger that long-promised ‘additional support’ to help pupils prepare for the tests.

Both the SQA and the Scottish Government are clearly desperate for exams to go ahead ‘as normal’, and it looks very much as though they are busy stacking the deck to make sure they get their way: not only has the bar for action this year been set absurdly, almost impossibly high – those in charge are also doing their best to block off alternative routes.

But the reality is that there has already been too much disruption for exams to go ahead fairly. All over the country education has been hugely impacted by Covid-related issues, and these problems have not been felt uniformly across all schools. A national exam diet by definition cannot make allowances for the sort of circumstances in which we find ourselves or the experiences of young people over the previous year.

Given that reality, why would the high heid yins be so desperate to protect exams? That’s depressingly simple: they’re actually just desperate to protect the status quo.

In order to achieve that, they want you to forget everything we have learned in the last couple of years and instead go back to believing that our ‘traditional’ exam system is a model of fairness and good sense – a level playing field on which all young people compete as equals. They’re assuming that you’re too tired, or too stupid, to remember why that’s a lie.

People who want you to believe that our exam system is fair often argue their case on a seemingly undeniable basis: if all pupils are sitting the same exam, at the same time, under the same conditions, then nobody has an advantage over anyone else. If you adopt a wilfully simplistic approach then you even get to pretend that it’s true.

Yes, everyone sits the same paper at the same time – but the notion that they are therefore sitting the same exam is a particularly destructive myth, one that I tackled in my recent book, Class Rules:

It is true that every student sits the same paper at the same time, but the idea that they do so under the same circumstances is a delusion, one built on the entirely false assumption that only the conditions inside the four walls of the exam hall have an impact on a student’s test scores. A student who got eight hours of sleep in a warm bed doesn’t sit their exam under the same conditions as one who woke up cold during the night because there was no gas in the meter. A young person who starts the day with a healthy breakfast and a chat around the kitchen table isn’t being tested under the same circumstances as one who had no time to eat because they had to make sure their siblings were ready for school. Pupils who walk into the exam hall thinking through their revision material are not being treated the same as the those who goes in worrying about the health of the parent for whom they are a carer.

These sorts of divides are not even particularly extreme examples — they are the stories that play out every single year in every single school in every single part of the country. But we don’t like to talk about it because the lie of the meritocratic exam system makes us feel better. We tell ourselves that the current system is fair because it is easier to believe the lie than confront the truth.

The high-stakes, make-or-break nature of the Scottish system demands that pupils perform to the best of their ability on single day — less than 0.3 per cent of a full year. It rewards those able to jump on command and punishes those whose circumstances mean that their best day might not happen to line up with a national exams schedule. This leaves our current approach inherently weighted towards those from more affluent backgrounds: those whose parents can afford private tutors, of course, but more broadly those who are just far less likely to be coping with emotional, psychological, social or family problems at any given time.

Another key feature of the system is the mechanism by which final grades are determined. Lots of people are already aware that the pass marks for each course change every year – but why? The official, public-facing answer is that this process allows us to make little adjustments if a paper proved to be a little harder or easier than expected; a more honest answer would be that officials want to keep their spreadsheets in line. One of the most fundamental features of our system is the determination that a certain number of young people must receive a failing grade each year (whether they deserve it or not) and so pass marks can be manipulated to make sure this is achieved. The same applies to grade distributions

Despite all this, we’re still supposed to believe that the exam system exists to set poor kids free – but as the official data shows, this is simply untrue.

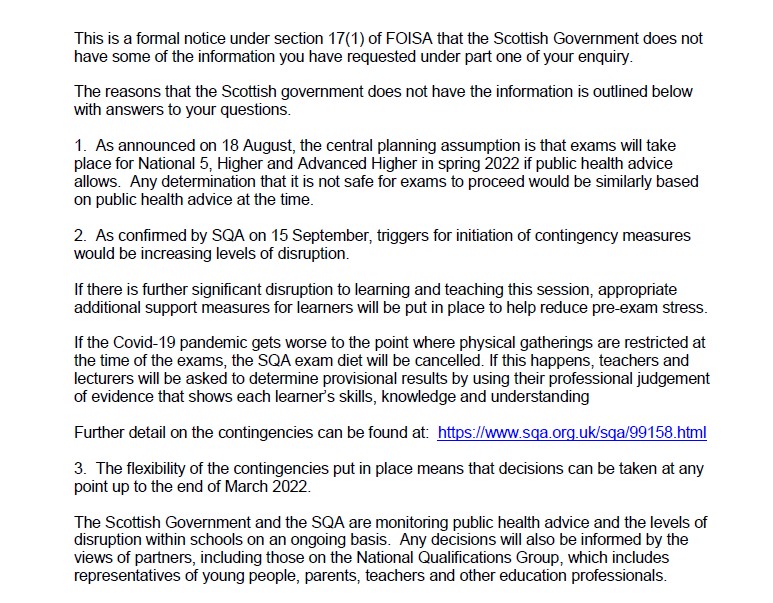

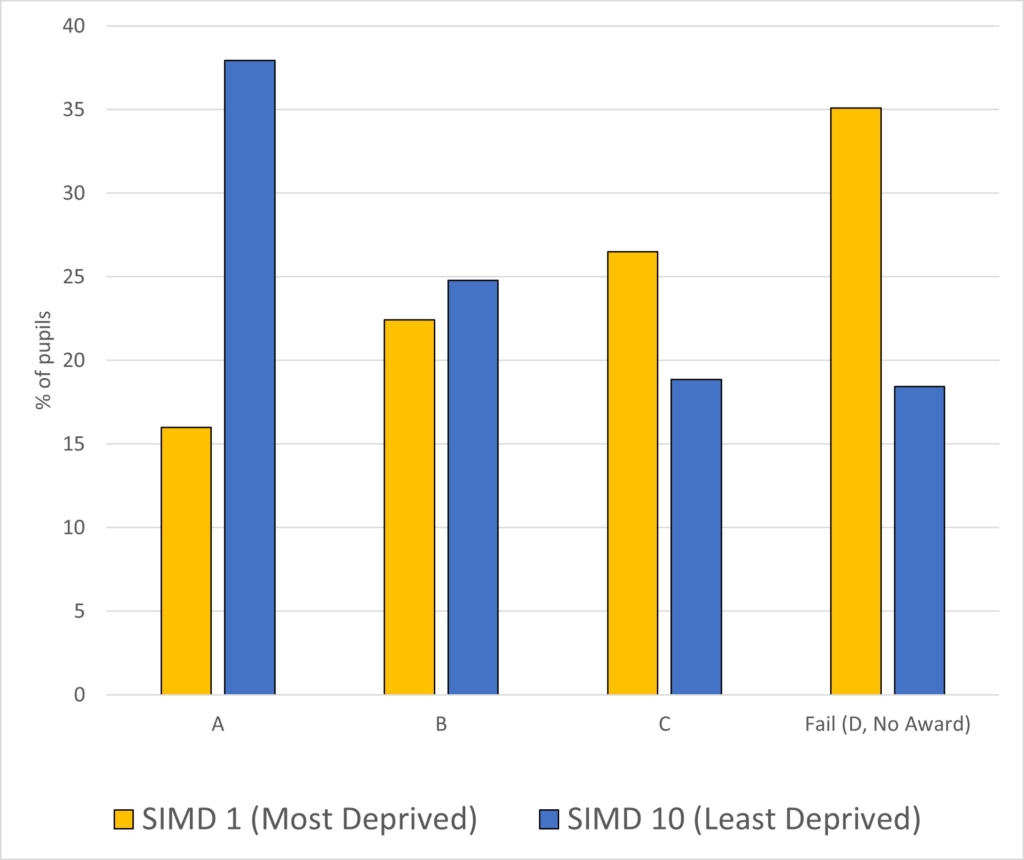

Perhaps the most direct way in which to analyse the exam system is to look at the interaction between students’ backgrounds and metrics such as pass rates and grade distributions. So we know, for example, that in pre-pandemic years, pupils from the poorest backgrounds were more likely to fail Higher courses than achieve an A, while those from the richest areas were more likely to get an A than any other grades.

HIGHER GRADE DISTRIBUTIONS 2019

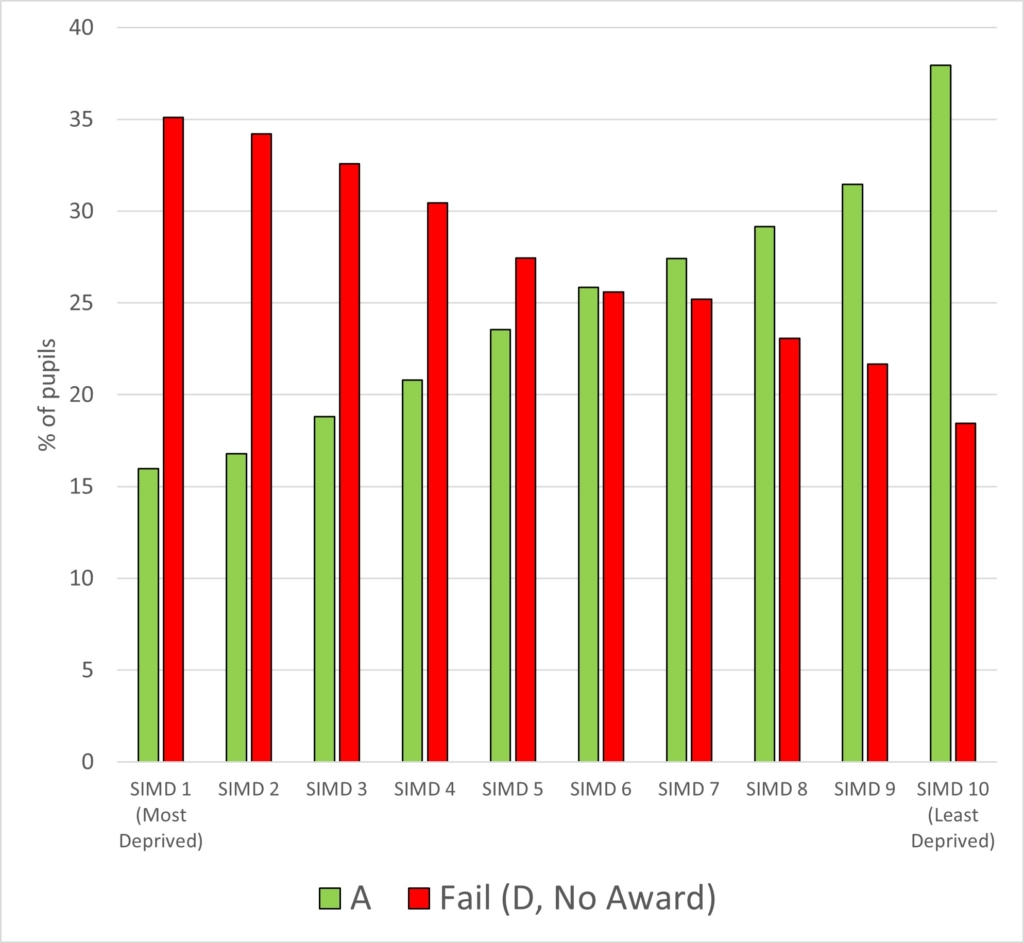

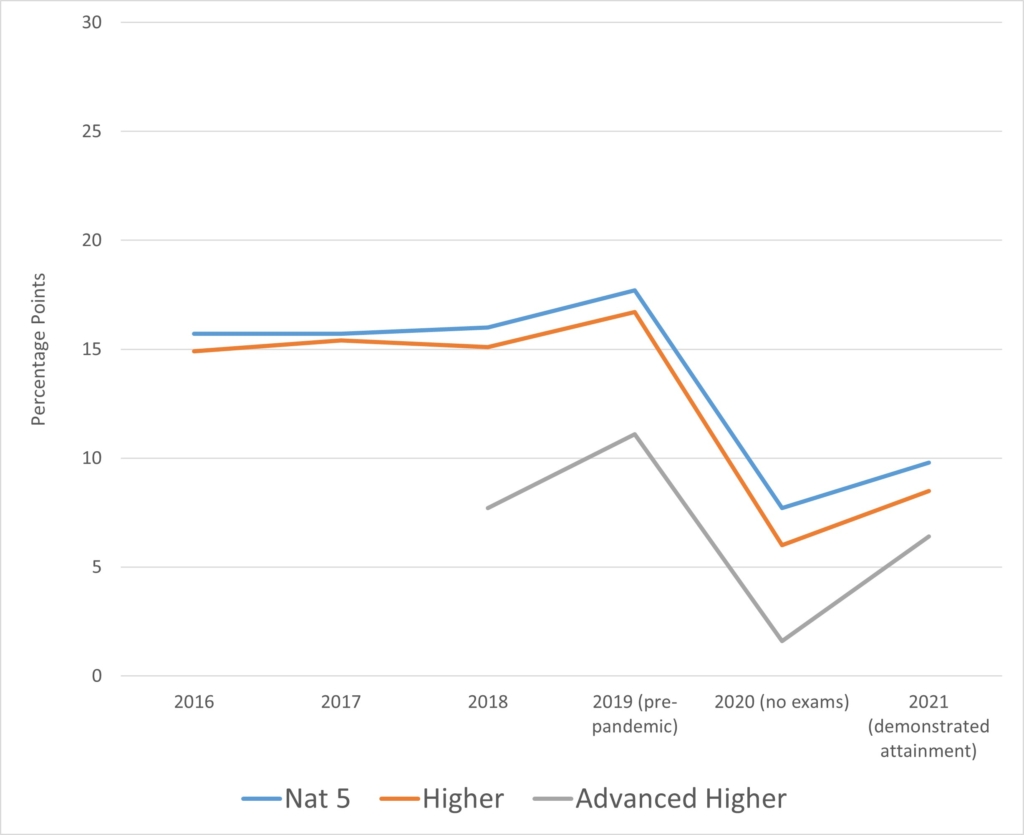

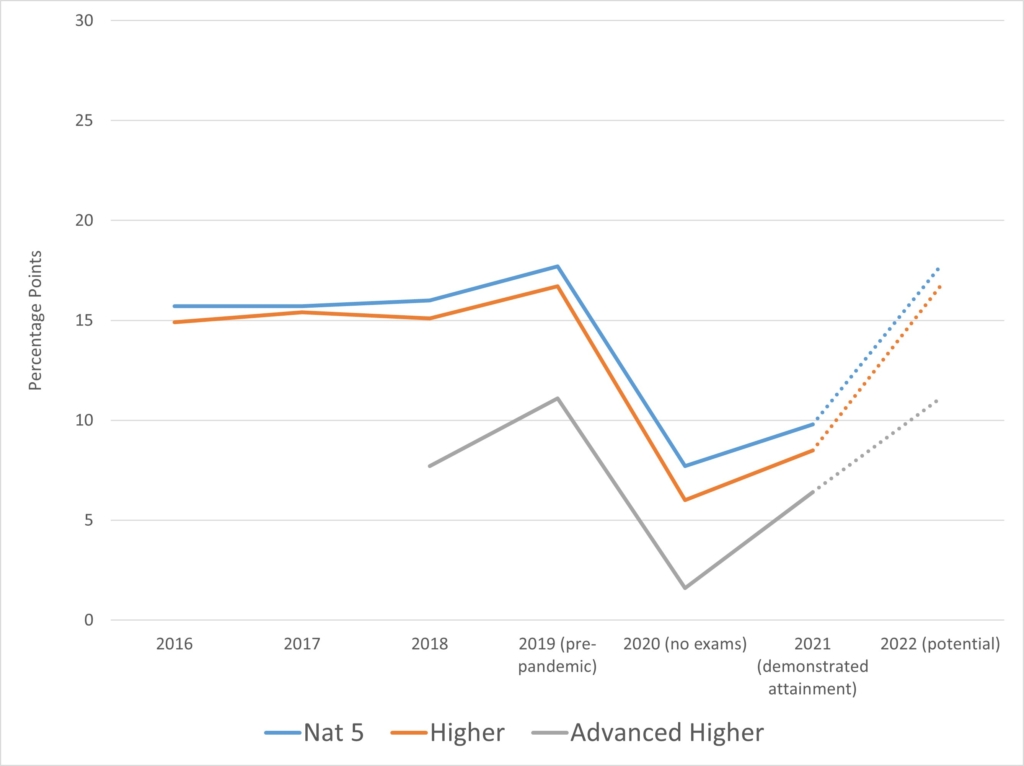

So that’s how the old system worked – but what about the last couple of years, when the pandemic has forced us to adopt different approaches? The most obvious impact of ditching the ‘traditional’ approach was a clear and significant narrowing of the gap between rich and poor. This occurred at National 5, Higher and Advanced Higher levels, and held for both years in which exams did not take place – although it is notable that the gap increased slightly last year when the ‘demonstrated attainment’ model was imposed and teachers’ judgements were not fully trusted.

NATIONAL 5, HIGHER & ADVANCED HIGHER ATTAINMENT GAPS (this chart shows attainment gaps as measured by the difference in pass rates between pupils from the most and least deprived areas of Scotland)

In 2020, and again in 2021, many people were quick to complain about ‘grade inflation’, by which they meant ‘too many poor kids doing too well’. Yes, pass rates improved – but what if this wasn’t anything to do with grades being ‘inflated’? What if this was grades being corrected? What if the size of the attainment gap we saw pre-pandemic was the result of the exam system magnifying, rather than mitigating, the already deep social inequality that exists in our country?

Under the systems in place in 2020 and 2021, pupils right on the borderline between passing and failing – which, let’s not forget, is a blurry, imprecise line that moves from year to year – were more likely to have their progress recognised and less likely to fail just to suit the whims of pen-pushers and spreadsheets. They were no longer forced to perform on demand on a single day either – in 2020 all of their work was taken into account while in 2021 students were could have more than one attempt at assessment tasks in order to achieve the grade that truly reflected their abilities. In short, pupils were treated more fairly by the emergency pandemic-era systems than by the traditional examinations approach, and as a result the gap between the richest and poorest pupils was smaller than it had ever been before.

And that raises major ethical questions about the desperate attempts to drag us all back to the bad old world. The problem is simple: going back to ‘normal’ means making the deliberate and unnecessary decision to reopen the gaps between deprived and affluent pupils.

NATIONAL 5, HIGHER & ADVANCED HIGHER PASS RATE ATTAINMENT GAP PROJECTION (this chart shows the increase in attainment gaps if examination systems and grading profiles return to 2019 ‘normal’ levels)

2020 showed us that these people think that fairness is when you discriminate against the those with least in order to protect the privileges of the middle classes. In 2022 it’s clear that they haven’t changed their minds – as far as they’re concerned, a system weighted in favour of the most affluent is what justice looks like.

They want us to go back to pre-pandemic normality. They want people to stop asking them difficult questions about equity and class-based discrimination. They want the privileged to keep their advantages, above all the preferential access to rationed university places for their kids.

Two years into the pandemic, after the biggest education scandal of the devolution era, a follow-up that did significant harm to young people, and a litany of other shortcomings (including the complete failure to make classrooms safe) we are, I’m afraid, right back where we started: with the government desperate to protect the system and shore up the status quo, and willing to do so at the expense of large numbers of mostly poorer children.

The messages being sent by the SNP are quite clear: for teachers it’s “politics matters more than your pupils”; for affluent Scots it’s “we’ve got your back”; for the poorest communities it’s “get back in your box.”

James McEnaney is a journalist, author, lecturer and former secondary school teacher. His latest book – Class Rules: the Truth about Scottish Schools – is out now.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

‘what if the size of the attainment gap we saw pre-pandemic was the result of the exam system magnifying, rather than mitigating, the already deep social inequality that exists in our country.’

There is another, more plausible, take on the relationship between the exam system and inequality. The exam system reflects existing social inequality. It can be argued that schooling should be able to mitigate inequality; I would hope that would be the case. However. if schooling fails to do that, attempting to achieve equality – at the last minute – via exam results – would be counter-productive. It would lead to a loss of confidence in the exam system which would make a bad situation worse. Making a situation worse, is something of a speciality with those in charge of Scottish education, as the creation of Curriculum for Excellence showed clearly.

James McEnaney is relaxed about grade inflation. I think he is wrong on this. When a year of massive disruption to schooling leads to – on paper – a huge increase in the levels of attainment, the credibility of the educational system, teachers as well as the SQA, comes into question.

The evidence that deprived areas perform less well that affluent ones has been there for all to see since Michael Forsyth forced the publication of exam results a generation ago. Despite what Nicola Sturgeon has said on the matter, there is very little sign, from politicians or from the public, that dealing the attainment gap is a priority.

Thank you for this article, James. And thanks to Bella for publishing. Too many parts of the Indy movement are willing to overlook these failings (a criticism which is not directed at this website).

Thanks for this – it supports what I and many parents think. I had big hopes that the issues with the SQA and in Education Scotland would lead to an opportunity to engage in a discussion

about examinations and their place in our children education. But no, it’s solidly ‘business as usual’ the same way that many businesses want things to be ‘back to normal’. And so this years 6th year pupils have to take exam hall tests for the first time, even when the examination body has been labelled for dismantling.

If normal isn’t the best option for the greatest number of people then we need to change it.

What is the international comparison? I found this older article but it does not help that much: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/aug/12/school-exams-covid-what-could-uk-have-learned-from-eu

German education could be particularly interesting, with federal devolution and different types of secondary school, where I suppose vocational programmes could be more objectively evaluated than academic ones.

HOW CAN ORDINARY CITIZENS MEANINGFULLY IMPACT EDUCATION?

Despite discourses of parent and community involvement in education, educational policymaking processes in Scotland are characterised as political spectacle: a drama wherein citizens are cast as passive observers of a small group of privileged decision-makers on a metaphorical stage.

EDUCATIONAL POLICYMAKING IN SCOTLAND AS POLITICAL SPECTACLE

Political spectacles are political constructions of reality that appear to serve the public good but function instead to maintain established inequities. Elements of political spectacle include symbolic language, dramaturgy, political actors being cast as leaders, enemies, and allies, the illusion of rationality; the distinction between on-stage and backstage action, a disconnection between means and ends and the illusion of democratic participation. Political spectacles are designed to win public support for particular courses of action without giving that public any real say in determining those courses of action.

Policymaking processes in the political spectacle are undemocratic. To use the metaphor of a theatre: in political spectacles generally, ordinary citizens are cast as passive audience members who watch privileged policy actors on stage. What the audience does not see are the policy negotiations and exchanges of material benefits that take place backstage. Political spectacles thus conceal real policy costs and benefits, make democratic participation in policymaking more difficult, and promote the status quo or prevailing matrix of power relations in society and the inequities those relations produce.

Political spectacle withers in an atmosphere of direct democratic participation in politics and policymaking. Policymaking processes that are grounded in direct democracy are an alternative to those that are grounded in the political spectacle. Direct democracy is committed to equality, diversity, and critical thinking, as well as to the direct participation of citizens in making decisions that affect their lives. This perspective demands that all aspects of policymaking are inclusive, equitable, and pursued in the interest of the common good rather than in the interests of the status quo.

ANTIDOTES TO EDUCATIONAL POLICYMAKING IN SCOTLAND

There are three antidotes to political spectacle that could move our policymaking processes closer to the democratic ideal: clarity, art, and direct action.

Clarity requires that everyone understands the particulars of everyday life for the schools under their governance. This understanding arises, not from information mediated by civil servants, but from sharing in the day-to-day experience of teachers, pupils, parents, and their support workers in their local community.

Art (e.g. dance, writing, painting, theatre, and film) is a second antidote to political spectacle. Art challenges political spectacles by helping people look at the world in new ways; that is, through the eyes of the artist. By expressing their day-to-day experience of teaching and learning creativity, in their own voices, teachers, pupils, parents, and their support workers can immediately share their unique day-to-day experience of teaching and learning in the specific context of their local community.

The third antidote to political spectacle is direct political action. Through direct political action, schools and the wider communities in which they are embedded can challenge the spectacle of educational policymaking by means of strikes, disobedience, and dissidence in defence of their own policymaking in response to their own locally identified needs. Direct action thus both requires and engenders a counter-culture of community development.

EDUCATIONAL POLICYMAKING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

Community development is grounded in the belief that community conditions are shaped by power; thus, on the community development model, the task is to alter power relations within the institution by means of direct political action so that currently less powerful citizens can influence policy processes in ways that improve their lives by further increasing their power.

Community development is also grounded in social capital theory. Social capital is the resources inherent in the relationships between people that help them achieve collective aims. Community development works by recovering resources like schools from bureaucratic governance and thereby transforming them from units of production – qualification factories or grading plants – into an element of social capital.

The root problem with Scottish schools lies not with this or that government policy but with the undemocratic ‘spectacle’ of our educational policymaking. The governance of our schools needs to be radically decentralised and democratised and thereby recovered as part of the social capital of the communities in which they are embedded.

@MysticMeg, if you mean lobbyists, vested interests, anti-democratic UK institutions, corporate and foreign state funding of politics, and political corruption (amongst other influences), why not say so? Boil down the bubble-babble of stale theory to something more amenable to political science, perhaps. You also seem oblivious to the uses of art in the service of power, persecution and profit. A pity that British imperial security state is considerably less transparent than even the USA, where at least grudging FOIA requests are available to persistent academics like the authors of National Security Cinema: the Shocking New Evidence of Government Control in Hollywood.

I expect it is too soon to tell what impact the Curriculum for Excellence’s plan for political literacy has had, but it did call for pupil participation in classroom decision-making, which seems a game-changer from old authoritarian models; and though it seems this had cross-party support, unsurprisingly it seems that reactionary forces inside and outside of the teaching professions opposed this (covertly, at least) from the start. Perhaps they were afraid that pupils might start grading their teachers.

https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-02/Young%20people’s%20political%20literacy%20and%20the%202021%20Scottish%20Parliament%20election.pdf

Although the CfE approach is somewhat weighted to electoral politics, the linked briefing does open the field of discourse wider: “interest may be stimulated when conflict or the efficacy of the democratic process is the subject of widespread news coverage and debate”.

CfE doesn’t have a plan for political literacy; in fact, it doesn’t ‘have’ a plan for anything. It is itself a plan, which is based on a holistic understanding of what it means to be a young person growing up in Scotland today, and which has as its aim the cultivation of active citizenship as opposed to passive subjection, of learning as the active making rather than the passive reception of established knowledge. It privileges autonomous learning over the negotiation by students through particular set programmes and discrete subjects.

Decisions about how the CfE is implemented rest with Local Authorities, their schools and teachers, with headteachers being responsible for the day-to-day implementation and management of the curriculum. The trend (which needs to continue for the remaking of Scotland as a more decentralised and democratic society) is to make government and its bureaucracies less prescriptive in what and how young people learn.

In the international comparison, ‘Implementing Education Policies: Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence: Into the Future’, which it published in June 2021, the Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques (OCDE) identified several areas in which further policymaking is required; namely:

Quality and Equity – policymaking is required to both raise the educational attainment bar and close the attainment gap for and between learners; too many learners are still under-attaining in comparison with their peers.

Decision-making and Governance – policymaking is required to absorb teachers, parents, students, communities, and the public at large into the shaping and management of learning in their schools.

Networking – policymaking is required to facilitate the sharing of good practice and materials in curricula design between communities of teachers and learners.

Assessment and Evaluation – policymaking is required to monitor the performance of schools in producing positive experiences and outcomes for learners in terms of their personal growth as successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens, and effective contributors to the public good.

My beef with the Scottish Government is that it makes a ‘political spectacle’ of this policymaking, conducting it from the top down, as a kind of bureaucratic rather than a democratic exercise, which kind of defeats the very purpose of CfE.

@MysteryMegaphone, I once tried to unionise my fellow pupils and failed, but whether because of my characteristically-half-hearted efforts, a general apathy or deference (or what Elaine Scarry calls the ‘seduction to stop thinking’), or a lack of a current cause célèbre, or some covert counter-revolutionary activity that escaped my attention, I don’t know. What I am pretty sure about was that failure to unionise pupils had nothing to do with performative politics. Perhaps you could just screen Salt of the Earth (1954) in our classrooms: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_of_the_Earth_(1954_film)

CfE gives people in Scottish education a new toolset. But the forces invading our classrooms are strong, persistent, well-funded and often ideologically cohesive. This Little Kiddy Went to Market: the Corporate Capture of Childhood, by Sharon Beder, with Wendy Varney and Richard Gosden, chapters on Teaching Consumer Values and Turning Schools into Businesses, amongst others, detail some of the mechanisms. Your local fossil fuel factory will be offering school trips and goodie bags. Your local ‘patriot’ chapter may be trying to infiltrate schools to wrench teaching back to ‘chalk and talk’ and the ‘three Rs’ (unfortunately not Reduce, Reuse and Recycle). Social media surrounding education debates may repeatedly feature opinions that children are spoilt (presumably from not being beaten in class), too outspoken (what kind of person wants children not to speak out?) and too questioning of authority (ditto).

None of this can be blamed on ‘performative politics’, which you rather than politicians appear to be using as a smokescreen. At least people can view the workings of the Scottish parliament, can consult archives, can write to their MSPs, can read media reports and opinions about them, and so on: there is basic (if limited and flawed) accountability. They cannot have access to the various corporate HQ meetings on forcing their planet-ravaging burgers or plastics or health-destroying fizzy drinks into classrooms with funded ‘educational’ propaganda; nor to the various royalist institutions which have great influence (royal-chartered BBC education programs, royal-chartered universities, royalist military recruitment and so on).

I’m not sure what point you’re making. Are you saying that the governance of our schools shouldn’t be decentralised and democratised and thereby recovered as part of the social capital of the communities in which they’re embedded because that would lead to the corporate capture of that governance? If so, why would it?

@MegalithicMethusalah, firstly, netiquette impels me to politely recommend that you use the comment form boxes for the purposes their label indicates, so some stable name goes in the Name field and so forth, and you can put your @s in your Comment.

Secondly, I had a bit of a larf at your railing against ‘top down’ instruction, since your whole schtick seems predicated on it. But let that pass.

Thirdly, and most importantly, you fallaciously and uncritically link decentralisation and democratisation. Try to let some empiricism impinge upon your theorising. We have had many examples where decentralisation of public services (not least education and health) has been anti-democratic, either authoritarian (the Thatcherite rash of managerialism) or permeated by interest groups such as churches (decentralising education for Catholics has hardly led to democracy) or corporations. One of the clearest examples was taking further education colleges out of local government purview which led to a constellation of mini-fiefdoms, and a lack of collective bargaining and idea-sharing, and a decrease in democratic influences and accountability. Your penchant for Balkanisation is hardly going to help share good practice and would indeed make it easier for corporations and ideologues to gain footholds at local levels. Rather than a thousand flowers blooming, history suggests a thousand mushrooms growing in the dark.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Managerialism#Political

Okay, so you are saying that the governance of our schools shouldn’t be decentralised and democratised and thereby recovered as part of the social capital of the communities in which they’re embedded because that would lead to the corporate capture of that governance.

But would it? The examples of decentralisation to which you allude were associated with privatisation, with power being transferred from the state to private individuals and corporations. But I’m arguing rather for an association of decentralisation and democratisation, in which power is transferred not from the state to private individuals and corporations, but from the state and/or private individuals and corporations thereof to the demos or ‘commonality’.

Basically, I’m arguing that we should take the governance of our schools out of both state and private ownership and into common ownership. That’s democratisation, and decentralisation is a condition of this.

@MuddledMisconsterer, clearly I am not arguing against democratising schools, I am arguing that democracy is more likely to happen at scale, just like when the Skolstrejk för klimatet emerged at global critical mass. Scottish education relies on shared services such as digital network GLOW Scotland, whose technology and practice should be collectively democratically steered, and whose digital commons forms the basis of an educational idea communism. https://glowconnect.org.uk

‘I once tried to unionise my fellow pupils and failed…’

Your mistake was to try and unionise your fellow pupils, to cast them as sheep and yourself as their would-be shepherd. Unions form immanently in response to the collective perception of a shared interest; they can’t be engineered ‘from the outside’ by some transcendent agency. Had your fellow pupils collectively perceived a common interest, unions would have formed among them without your intervention and within the commonality or community of which you might subsequently have found a role, place, or belonging.

@MaunderingMuppet, you are projecting your pastoral fantasies and ‘will to power’. Far from seeking any shepherding role, which sounds like a lot of work, I only intended to act a catalyst, a piece of grit that the pearl of collective action could coalesce around. This is the kind of thing now modelled mathematically in social dynamics, with initiators, influential relationships and network topology. Essentially, how grassroots politics work.

https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/people-networks-and-neighbours/0/steps/230049

‘…a role, place, or belonging.’

‘Eine Heimat’, as the Germans say.

WHY SCOTLAND SHOULD LEARN TO SAY ‘HEIMAT’

The German word Heimat is often said to be untranslatable. Roughly meaning ‘home’, Heimat is booming (again) in German popular culture. In Munich, there’s a specialist store for Heimatliebe und Herzlichkeit (‘love of one’s home and cordial warmth’). What the shop actually sells is local travel guides, ‘ironic’ antlers and cuckoo clocks, and Bavarian recipe books.

While this is Heimat with a Bavarian flavour, regional traditions — or ‘kitsch’ — are thriving everywhere, including in Scotland. You can read Heimatkrimis (crime novels) set in Edinburgh and Shetland, browse Heimatblogs about Govanhill or Kirkcudbright, or flick through glossy magazines dedicated to country living and Heimatliebe.

In present-day Scotland, however, 71% of the population live in towns or major cities rather than the countryside. The same generation that’s the target audience for hipster skirts with a tartan print takes globalised experience for granted. What possible resonance can Heimat have for cosmopolitan urban Scots?

HEIMAT AND HOME: OLD WORDS FOR ESSENTIAL NEEDS

‘Heimat’ sometimes pops up in vocabulary lists that make the rounds on the internet; lists of words that should exist in English or that are impossible to translate. While translation isn’t impossible, it is hard to find one with all the same implied meanings.

‘Heimat’ contains the German noun ‘Heim’, which — as you may have guessed — is very closely related to the English ‘home’ and the Scots ‘hame’. It’s one of the oldest words in these languages, going all the way back to early mediaeval Old High German and Old English.

If you want to get really Heideggerian, the words are even older. Both English and German are Indo-European languages. Whether we say ‘Heimat’, ‘hame’, or ‘home’, they all have their origin in the ancient South Asian language Sanskrit from a verb that means ‘to stay’, ‘to live somewhere’, ‘to dwell’.

Those 3,000 years of linguistic history highlight some of the oldest and most important human needs: to have a place to stay, gather round the fire, share your food, and feel safe.

IS ‘HEIMAT’ A BAD WORD?

Heimat has all the positive connotations of feeling at home, where it’s warm and safe, but it hasn’t always been an uncontroversial word.

At best, ‘Heimat’ is something slightly old-fashioned, full of naïve sentimentalism, a simplistic idyll far from reality. In the 1950s, ducks and antlers were a very popular and completely unironic kind of wall decoration, and the era’s most successful movies were what the Germans call called Heimatfilme (‘homeland films’); that is, feel-good flicks full of technicolour scenery and black-and-white morality, which are still occasionally broadcast on cheap TV channels decades later.

At worst, Heimat can be even direr than suffering yet another rerun of Whisky Galore with your aged relatives. It can be provincial, narrow-minded, or exclusionary. It can also imply protecting your home from something scary, or just from someone else, from those who are not ‘from here’, those who have the ‘wrong’ language, dialect, customs, religion, or skin colour, those whose family hasn’t lived here for hundreds of years.

HOME IS NOT (ALWAYS) A PLACE

What if you can’t trace your local family tree back a dozen generations? If you identify with more than one region or country? Or if you live a migratory or nomadic existence? What is your Heimat? Is it your birthplace? Your parents’ birthplace? Your grandparents’ birthplace? The place where you’ve lived the longest?

There is another meaning of ‘Heimat’ and its cognates that hasn’t been mentioned yet. From its earliest usage in the Germanic languages, the word has always told a story of loss or longing. There’s no place like home, where ‘home’ isn’t necessarily a place.

In more religious times, home was only found in heaven. Centuries later, the Death of God turned the concept of humanity’s home into a more secular thought. Maybe humankind is doomed to be Heimatlos (‘homeless’) in an existential sense, Nietzsche might have suggested, always longing to belong somewhere but never arriving anywhere.

Fortunately, you don’t need to start reading Nietzsche, Heidegger, and their French students to get a feeling for that sense of Heimat. It’s right there in the word ‘Heimweh’, which translates as ‘longing for home’ or ‘nostalgia’, the ache of coming home. It’s a very familiar feeling, that search for familiarity, safety, and love. Just listen to Dougie McLean or Frankie Miller yearning for ‘Caledonia’ on Spotify.

MAKING IT HOME

Today, the world seems smaller than ever; globalisation has brought the world to Scotland. We have more opportunities to explore other cultures, more connections with other people, more freedom to find our place in life, our own identity, which (again thanks to globalisation) is no longer a given. Expanding our horizons can be both exhilarating and unsettling, and everyone reacts to it differently.

Some people prefer to go back to their roots, learn Gaelic, and read T.C. Smout’s History of the Scottish People and its successive iterations of the tribal mythos. Others just buy countryside magazines or ‘ironic’ kitsch, which secretly remind them of happy childhood moments spent in their granny’s living room.

Yet others find a home in the feeling of Heimat itself. The German Duden dictionary also defines ‘Heimat’ as an ‘emotional expression that suggests a strong attachment to a specific place’. It doesn’t matter if you were born in that place or how long you’ve lived there or have inherited its past as part of your cultural baggage. It only matters that you feel a sense of belonging, that you have finally arrived. Home is where the heart is, and a’ that. and a’ that (it’s coming yet for a’ that).

There’s a German term for that too: ‘Wahlheimat’; the home you choose.

Now that’s a word that Scotland should definitely learn to say.

‘Essentially, how grassroots politics work.’

But don’t you think that the decentralisation and democratisation that make grassroots politics ‘grassroots’ leave it susceptible to corporate capture? Surely, this is precisely why you think grassroots governance of our schools is a bad idea. Or have I misunderstood your previous posts?

And why on earth is ‘democracy… more likely to happen at scale’ rather than at grassroots level?

@MutteringMince, grassroots and large scale are not exclusive, and I have already given the examples of climate school-strikes and collective bargaining. Shared services (like GLOW and JISC’s infrastructure and information services) provide a set of commons where parliaments and communities of interests can flourish. But limiting democratic initiatives to the school level will cut off their networking abilities at scale. To give a further example, pupils and students as well as teachers and lecturers can contribute to open education resources, but their full potential is only released at scale, and with barriers to adaptation and reuse removed, and that requires standardisation, and for that standardisation to work it needs coordination of policy. Schools may have teachers and pupils with specialisations, or resources, that other don’t; while cross-institutional collaboration can achieve works that individual institutions could not. This is what the advocates of OER are saying, and how they link to international initiatives:

https://openscot.net/further-education/open-educational-resources-an-equitable-future-for-education-in-scotland/

Clearly, OER and similar idea communisms run counter to commercial exploitation of the education market.

Who’s talking about limiting democratisation to the grassroots level of individual schools? Education needs to be democratised at every successive subsidiary level of generality also, right down to the national level (and beyond). This point has been made time and time again, in relation to education and other civic institutions. Have you not been paying attention?

BTW You still haven’t said why you think the decentralisation and democratising of education in Scotland would make it more susceptible to corporate capture.

It seems Mr McEnaney is looking for quantifiable answers but is only receiving qualified answers. Don’t see how the SG could do otherwise with a virus that was constantly evolving different and unknowable threat levels and trajectories.