Adults Learning, Democratisation and the Good Society

This is a long-form essay of biographical reflection on fifty years of work taking in the social history of community action and thoughts on religion, poverty, psychology and politics in Scotland. This article was first published in Convergence (vol 43, no 1, 2022), a global adult education journal linked to UNESCO by Colin Kirkwood, with Gerri Kirkwood.

This article reviews fifty years of personal contributions and experiences in adult education, community action, counselling and psychotherapy in Scottish, English and international settings. It reflects on what teachers, learners, enablers and activists were trying to achieve through their engagement, and proposes a set of foundational rights, responsibilities and resources for all persons in community and society, for now and the foreseeable future. The context of teaching, learning, enabling and activity of all sorts is always our whole world: our immediate physical and interpersonal environment in the whole world at every level of scale, simultaneously present and interconnected. Our worlds are usually in crisis, internally and externally, and that is true as I write, now. The paper is written by me, Colin Kirkwood, and refers to views of my wife and life partner, Gerri Kirkwood.

Gerri Harkin and I were born in 1944, Gerri in Lennoxtown near Glasgow and I in Edinburgh. We both came from Scottish and Irish backgrounds. Gerri’s parents originated in the twin towns of Ballybofey and Stranorlar in Donegal. They had two children and lived in Glasgow in Riddrie, Kinning Park and Bath Street. Her father was a commercial traveller and later worked for MacAlpines in various locations throughout Britain. Her mother worked as a nurse in Coventry during the 2nd world war, and later as a housewife and mother and had part-time jobs in shops such as RS McColl’s. She took in lodgers, some of whom laboured on the Clyde Tunnel. Colin’s parents came from Mallusk and Belfast in Ulster. They emigrated to Scotland in 1942, where his father became a presbyterian minister in Bathgate, Watten, Dundrennan and Saltcoats. His mother, though trained as a teacher, was a housewife and mother throughout her adult life.

Both of us come from religious backgrounds: Gerri Catholic, I Protestant. The conflicts between Catholics and Protestants were stark, fascinating – and normal. The cultural gap was enormous, based on history, but also on prejudice, ignorance and fantasy. Gerri loved going out (against her mother’s wishes) to watch the antics of the Orange marchers in the south side of Glasgow. I thought I knew no Catholics, growing up in Saltcoats, but like everybody else I frequented Italian cafes such as the Café Melbourne and the Marina and associated fish and chip shops. Italians were seen as tallies, and their cafes were an unqualified good, so their Catholicism was not significant. It was not until I went to Glasgow University in the autumn of 1961 that I met and got to know Catholics including Bob Tait, Tom Leonard and later Gerri Harkin. In the summer of 1967 we were married in St Patrick’s Church in Glasgow by Father Anthony Ross, then Catholic Chaplain at Edinburgh University and later head of the Dominican Order in Britain. Our best man was Bob Tait, poet, philosopher, generalist and ground-breaking editor of cultural magazines Feedback and Scottish International. Immediately thereafter, we turned away from religious doctrines and dogmas, beliefs and practices, but the values and cultures of these religions have continued to influence both of us deeply throughout our lives.

Like Bob and many of our generation, we regard ourselves as generalists. Gerri is a lover of languages (English, French, German and Italian). As well as French and German, Gerri studied Logic, Fine Art and Architecture in her first (general) degree, and she has returned to all of these interests in a cross-disciplinary way throughout her life.

I went to Glasgow University to study European History, abandoning it in favour of English and Scottish Language and Literature, and Moral Philosophy. Throughout my childhood I had been intensely self-conscious and shy. I found it difficult to speak on my own behalf, particularly in the company of girls. I began to find my voice paradoxically through writing, in English classes taught by Jack Rillie and Edwin Morgan, and William Maclagan’s Moral Phil class. In essay writing I refused to read any critical works, insisting instead on reading only the actual works of the poet, dramatist, novelist or philosopher the set essay was about. I felt strongly that I had to work out my view of these writings myself. It was to my teachers’ credit that they accepted this practice. I also began writing my own poetry, and on completing my first degree I was given a two year grant to study Objectivist and Imagist Traditions in Modern American Poetry. Throughout those years 1961 to 1967 I discovered a love of sounds, syllables, words, phrases and rhythms, in my admiration of the work of DH Lawrence, WB Yeats, Kenneth White, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Villon, Baudelaire, some of Pound, Robert Creeley, the Beats, Denise Levertov, Marina Tsvetayeva, Andrej Voznesensky and Scottish Renaissance writers like Robert Garioch, Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean. To my astonishment, my own work was broadcast and published.

My life has been full of contradictions and paradoxes. Having reached the age of 77, I feel increasingly like my father, a late developer. But is that really true? Certainly, I am a generalist, an integrator, a promoter of dialogue, a lover of language–in-use, with a deep wish to enable others to find their own voices. But I am also at times impatient, irritable and outraged by rascality or opportunism when I come across it. I had no desire to become an academic teacher or researcher, or to reach the top of a profession. In my first published article in Adult Learning I wrote: “ I write as a practitioner with an interest in theory”. Exactly so. Still true today. And I am still driven to write. A central paradox of my existence has been that deep sense of unease I felt at being observed, combined with a strong wish to be accurately heard and understood. This must root back to seeing my father in the pulpit every Sunday, halfway up the wall in the church! I have retained throughout my life a deep distrust of institutions (which are too often used for personal promotion or advantage – or simply coercion), yet at the same time, unknown to me, there must have been a longing for a role like my father’s. In those days, ministers and priests, as well as being very badly paid, really were shepherds of their flocks, visiting each parishioner in their home or in hospital several times a year. A good minister like my father was loved for that reason. He frequently repeated and enjoyed the joke about members of the Kirk Session praying: “Lord, you keep him humble, and we’ll keep him poor!”

So I have been aware of no status ambition or salary ambition at a conscious level, yet I have feelings of outrage towards people who inflate their income through excessive expenses claims. At the same time, I had a sense of horror about the way the poorest people in society were treated, abandoned really, at the level not so much of general policy as of particular instances. My father had regular visits from women who had been beaten up by their husbands or partners, and homeless men who roamed the country and came to seek his help, often looking for food or money or both.

Treviso

At both primary and secondary school, I observed and myself experienced the horrific practice of belting children with a leather strap called a Lochgelly, or simply “the belt”. On the first day of my first job at Tollcross Junior Secondary School in Glasgow I was told by the head of department: “You’ll have heard all this nonsense about AS Neill and Summerhill. We belt them. Hammer them on the first day and you’ll have no problems”. Violence was at the heart of Scottish schooling then, reflecting the violence of Scottish society. Gerri and I quickly realised we had to get out, and did so. In the autumn of 1968 we found ourselves in the mediaeval/early renaissance city of Treviso in north-east Italy, where Dante went when he was driven out of Florence. I taught English to (mainly young) adults in the Scuola Interpreti. The astonishing light of September lit up not only the rivers Sile and Cagnan as they threaded their way through the streets of the town, to their merger at the Ponte Dante, but also the mediaeval, renaissance and even modern architecture. The American airforce had bombed some of the old areas of the centre, having confused Treviso with Tarvisio much further north, where the retreating German army was holed up.

What did we learn from Treviso, its people and their culture? Three things: first, culturally, the need to undo the reformation, and restore the beauty and good sense of Italian architecture. The rebuilding of the Via dei Dall’Oro, and the repairs to the Piazza dei Signori and other parts of the centre, demonstrated for example in the condominio style of blocks of flats, shops and offices, that there was an alternative to the crude utilitarianism and bleakness of British council housing. Second, the Catholicism versus Calvinism tension that we had grown up in diminished in intensity when we perceived the communitarian and feminine qualities Catholicism had to offer. Third, having tried hurriedly to learn how to teach by reading three Introductions to English Language Teaching, which left me no better at teaching adults than I had been at teaching children, it turned out that Gerri’s empathic style of affirmation, appreciation and appraisal, together with her intuitive mastery of all aspects of grammar, meant that she rapidly became the favourite of the middle and high ranking Italian Army officers she was assigned to.

After our return to London in June 1969 – to face the real challenges of change that were needed in our own society and culture – I continued to teach English for several months. I applied for and got the job of Area Principal for Adult Education in Staveley in north-east Derbyshire, where we remained for three years. It was the best thing that could have happened to me. The story and critical analysis of that work has been written by myself and Rob Hunter, and I do not intend to repeat it here. The personality of Rob, our work with the people of Staveley in the newspaper Staveley Now, the Staveley Disabled Group, the Staveley Festival, and our interactions with the local chapter of Hell’s Angels, their inspirational part-time youth leader, Joan Turner, and that good man, Eric Edwards, transformed us all. The social, physical and cultural context of mining, light industry, steel and chemical works, the mixture of industry, housing schemes, the old town centre with its ancient buildings, the fields, canal and rivers, plus Labour and trade union politics, was the backcloth of all our efforts and our learning. The way the natural landscape wove itself around and through the dark Satanic mills and the winding gear renewed my contact with the poetry and stories of DH Lawrence and my love for England and its people that has resisted the temptations of narrow territorial nationalism. At the same time it confirmed my distrust of institutions and encouraged my trust in ordinary people (who usually work for them!), their speech, their writings and their communitarian initiatives. Working with Rob, Joan, Eric, the two Keiths, Shirley, Fred, Oscar and many others set me and Gerri on a road we have followed ever since, as we returned to the challenge of the inner city and peripheral housing schemes of Glasgow late in 1972.

Castlemilk

Our first sally in Glasgow ended almost as soon as it started. We had joined YVFF, of which Rob was by now Assistant Director, in a community project based in Barrowfield, a small, very poor inner city housing scheme, with horrific levels of unemployment, and housing that was in a dreadful state. We had joined forces with a young architect and his wife, who turned out to be interested mainly in persuading these poor, marginalised people to march on their own against the city hall. We came to see him as a narcissist, and realised that the most sensible thing we could do was to withdraw from the project straight away. We did so. Gerri applied for and got a job as Reporter to Children’s Panels. We used her right as a resident of the city from birth to get our names on the council housing list. Normally that would have involved a wait of several years to be housed, unless you were prepared to accept a DTL. The letters DTL stood for a house that was difficult to let. Once we had signalled our willingness to do so, we were encouraged to drive round the city’s big schemes (Easterhouse, Drumchapel and Castlemilk) and take our pick. Castlemilk was easily the most attractive of the three, with its Cathkin Braes, mature trees and bluebell woods. We spotted a boarded up ground floor flat on the southern edge of the scheme, at 200 Ardencraig Road, across from the tower blocks of the Mitchelhill high five, and facing a Catholic Church Hall. We informed the Housing Department that we would accept it. Within days we were in. That would be late November 1972. The houses in Castlemilk, like those in Easterhouse and Drumchapel, were relatively new. But they were built and laid out in a style that resembled a prisoner of war camp without the barbed wire. Any relationship between this kind of environment and the participatory socialism of William Morris had been completely severed. A popular song of the time captures this reality:

Oh they’re tearing doon the building next tae oors,

And they’re sending us tae green belts, trees and flooers.

But we do not want tae go, and we daily tell them so.

They’re tearing doon the building next tae oors.

The buildings referred to here were the fine but dilapidated old tenements of the Gorbals and other inner city areas of Victorian Glasgow. In Castlemilk, initial attempts to cultivate front gardens and back greens had been abandoned by most residents, if they had ever begun. The bluebells in the bluebell woods still flowered, alongside discarded fridges, washing machines and mattresses. The mature trees still stood, but having lost their lower branches, looked forlorn. Across the road, the Otis lifts in the Mitchelhill high flats frequently malfunctioned. It didn’t take too much time to work out that the causes of these malfunctions were often acts of vandalism by the more alienated residents, Castlemilk’s angry young men.

In spite of all this, Castlemilk was not a bad place to live. The Communist Party had encouraged its members to go and live there, and many had done so. There were good Labour, SNP and even Tory people there too. Archbishop (later Cardinal) Thomas Winning had for years been encouraging recent Irish catholic immigrants to join the Labour Party and become politically active, and his efforts had borne much fruit. So the scheme was not an underclass hellhole, although the Housing Department’s appalling practice of grading people from very good to very bad, was generating at least one area of high unemployment, antisocial behaviour and occasional violence. Taken as a whole the scheme was a mix of everyone and anyone, except for the upwardly mobile and the already successful. It had one short shopping block consisting mostly of the Co-op, and also a swimming pool, a community centre, two secondary schools (one Catholic and one Protestant) and their feeder primaries, a doctor’s surgery, a housing/rent office, but no bank and no pubs, thanks to the efforts of the local Tory MP, Teddy Taylor. Only private clubs were allowed to serve alcohol, and the only private club in Castlemilk was the Labour Club, where the future Lord Provost of Glasgow, Pat Lally and his friends held court. I must not forget to emphasise the benign presence of several Catholic and Protestant churches and their priests, ministers and members, who were a leaven of loving humanity. In particular there were John and Mary Miller and their young family, of Castlemilk East Church of Scotland, who had just moved into the scheme to live, and who were to remain there for the next 35 years or so. John came to our house to welcome us within days of our arrival, as did another good man and good friend, Archie Hamilton, leader of the Communist Party in the scheme.

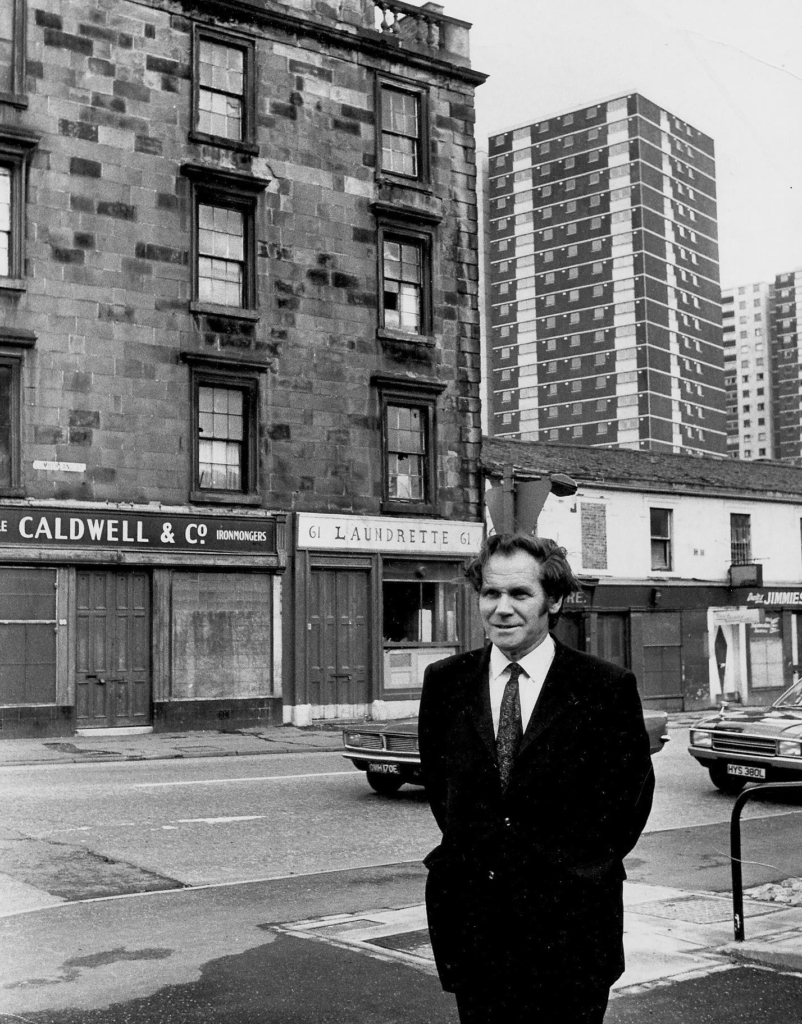

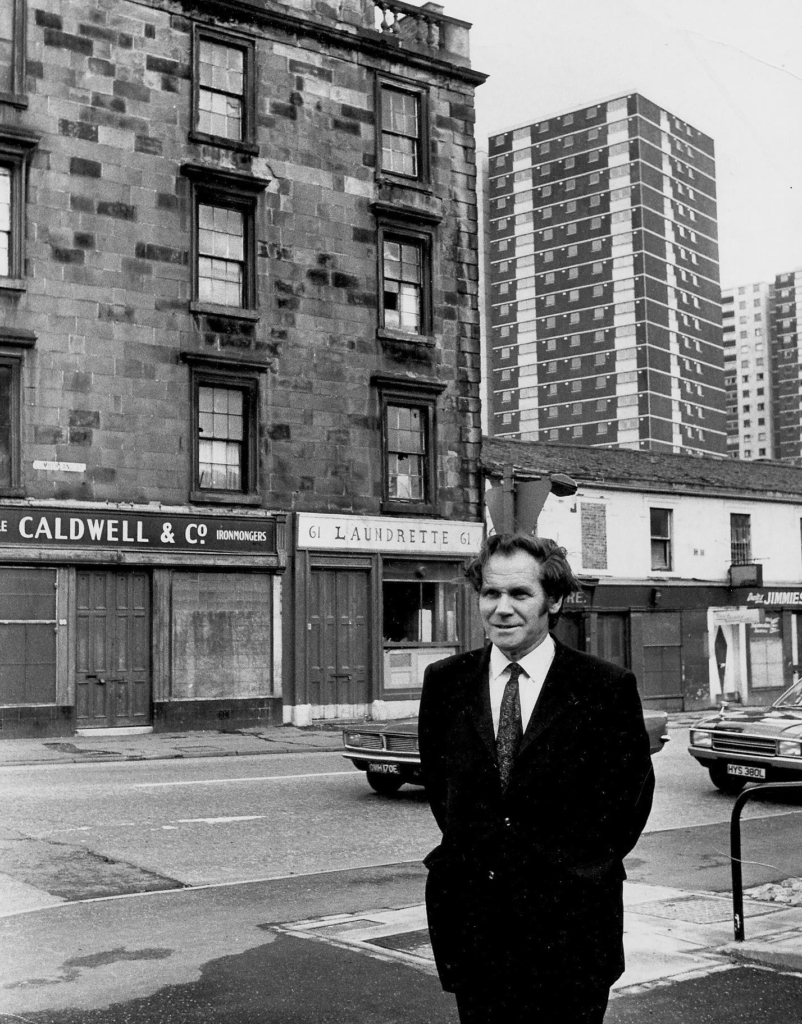

Geoff Shaw

Labour politics in Glasgow, like that in Derbyshire, was based on the general rule: leave it to us, that is, to the elected representatives, the councillors and MPs, and to state provision. But deference was declining, and community action was stirring across Clydeside. And Labour hegemony was about to be modified (alas not wholly transformed) by the decision of the radical Christians of the Gorbals Group (and to some degree also the Iona Community) to abandon their previous posture of political neutrality and join the Labour Party. Geoff Shaw, an outstanding and loving man, was shortly to become leader of the Labour Group on Strathclyde Regional Council. At the time, and still today, I thought they had made a terrible mistake. They should have joined the Glasgow Communist Party, whose working class activists they knew and admired, or – even better – created a new kind of open political movement. Geoff and his colleagues gave their all, and did their best to transform Labour. It was a bit like Jesus of Nazareth and his followers deciding to join the Mafia, and could only have one possible outcome.

I am not going to give an account here of what was done over the next four years: much of it is recorded in the first half of Vulgar Eloquence: the council tenants’ movement, the rents action campaign against the Housing Finance Act, the newspapers Castlemilk Today and Scottish Tenant, lifts action, community councils and the Horseshoe Steering Committee, and later and most outstanding – animated by Mary Miller, Carol Cooper, Irene Graham and others – the Jeely Piece Club. (In parenthesis, it should be noted that Castlemilk was not the only site of community action on Clydeside. Perhaps the most noteworthy was the Gorbals and Govanhill, led by Barbara Holmes and Richard Bryant and involving among many others Jeanette McGinn and Billy Gorman.)

What I cannot avoid speaking about is the murderous and destructive event which occurred in the autumn of 1975, which had a shattering effect on many of us. That year, John and Carol Cooper, Irene Graham, Gerri and I and others were heavily involved in various forms of voluntary community action. John and I had been speaking in one of the Secondary Schools about some aspects of that work. We had returned to our flat in Ardencraig Road for a cup of tea. John’s wife Carol phoned to say: “the wee yin’s no hame yet”. John and Carol and their kids then lived in the Bogany flats about 200 yards behind us on the other side of the bluebell woods. All of our kids attended the local primary schools. John and I became alarmed. We rushed out to the car and drove round to the foot of the flats at Bogany. There was a small crowd of kids. We jumped out of the car and ran over to find the body of a child on the ground. We quickly realised it was Georgette. John picked her up and between the two of us we got him and her into the back seat. I drove like hell down through the scheme heading for the Victoria Hospital, flashing the lights and blaring the horn to get through traffic lights. We got to the door of the hospital and carried Georgette in. We were treated with great suspicion, as if we had committed murder. Georgette was dead. She had been enticed or perhaps forced up to the top of the flats by a disturbed boy, who had pulled out a series of glass slats and forced her out. She fell ten or twelve floors. She had no chance.

That event had major repercussions not only for John and Carol and their remaining child, young John, but also for Gerri and me and our kids, and for everyone involved in Castlemilk and beyond. It was headline news. I don’t think I grasped the full impact it had on myself and everyone else at the time. Its long-term impact has reverberated down the years.

Georgette’s death did not end community action in Clydeside, and it was not caused by community action. But it was a terrible caesura, a great pause, in all our lives. I think if anything at one level it made me more driven, more committed to changing the society that could cause people such harm. It was a horrible demonstration of the potential for destructive violence in human beings and human society. It is greatly to the credit of Mary Miller, Carol Cooper, Irene Graham and others that out of that tragic event they created one of the most worthwhile and long-lasting outcomes of community action, the Jeely Piece Club, which was a summer playscheme and an after school club for children in the scheme, run by mothers both as volunteers and paid employees, on a self-managing basis.

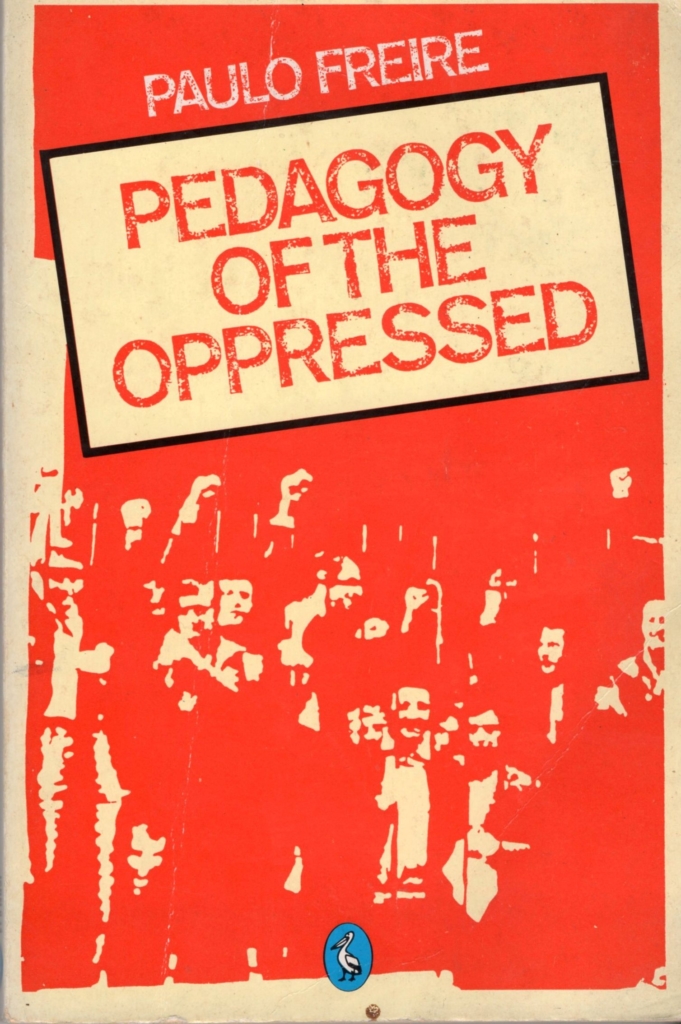

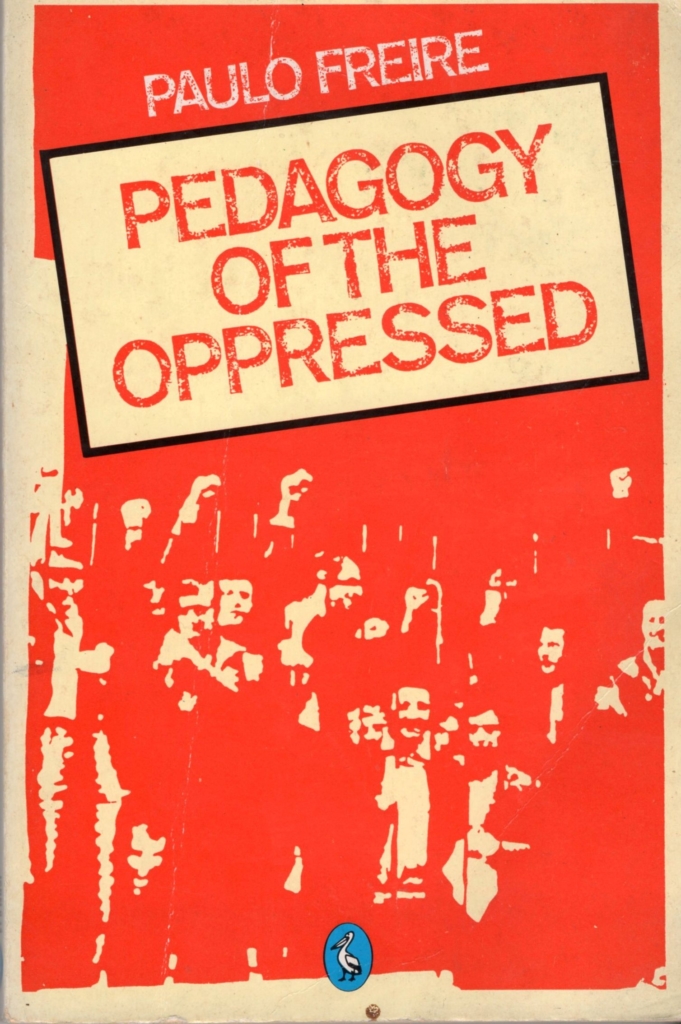

Well before the tragedy of Georgette’s death, Gerri and I had decided that I should get a full-time job again. Living on one salary alone was becoming difficult. Gerri had given up her job as Reporter to Children’s Panels, and I had embarked that autumn on a one year Master’s degree in Adult Education and Community Development at Edinburgh University, to which I travelled three days a week. It was a time of great intellectual activity and political ferment. I read widely about the colonial origins of community education and community development, and for the first time discovered the writings of the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, and the ideas and meaning of liberation theology and personalism. In the summer of 1976 I wrote my dissertation on Community Work and Adult Education in Staveley, graduated in September and began to apply for jobs. The job I got was Tutor Organiser for the Workers Educational Association in South-east Scotland, based in Edinburgh.

Leaving Castlemilk, Leaving the Communist Party

Those four years in Glasgow had been more than an eye-opener. They were a cross between a train crash and a challenge to my whole way of being in the world. They confronted me with a kind of violence in human society that growing up as a minister’s son in rural areas and then a small town like Saltcoats had given me no inkling of. Gerri and I were now 32. Our children were 8 and 5. We left Castlemilk in late September 1976, in my case with a sense of shame and guilt, as if I was leaving a sinking ship, yet also with a determination that I was not going to subject our children to the danger of the fate that had snuffed out Georgette’s life so cruelly. I had already resigned from the Communist Party, at Christmas 1975, leaving an organisation where I had found acceptance, encouragement and fellowship. Now I felt again homeless, again the outsider, but at the same time I was avidly reading Freire’s work. In Paulo Freire I found a man who had taken a terrible blow in his early teens, with the decline and early death of his father, and who was saved by the decisive action of his mother in persuading the head of a good school to take him in.

The Freirean work began almost as soon as we had found a flat in Edinburgh. I taught through the WEA a Pedagogy of the Oppressed reading group and later two extended courses on Freire’s ideas and methods. Out of one of these came the successful application by Fraser Patrick and Douglas Shannon to the Scottish Office for what became known as the Adult Learning Project or ALP for short. Fraser was an inspiring and ethically grounded leader who helped his team to adapt Freire’s ideas to Scottish culture and circumstances. He appointed Stan Reeves, Fiona McCall and Gerri Kirkwood as ALP workers. Together with the people of Gorgie, Dalry and later Tollcross they created a project which flourished from 1979-2019. It is written up in the first and second editions of Living Adult Education: Freire in Scotland (1989 and 2011).

One of the key contested themes of 1968 and also of Staveley, Castlemilk, Gorgie-Dalry, and indeed the whole world is the theme of authority. The belting dominie as the underlying model or stereotype of authority in Scotland has already been mentioned. Several centuries earlier, at English and British level, Kings were the dominant model, often beheading, burning or torturing their opponents. During the community education period in Scotland and England, there was initially a swing to enabling or facilitating, when these terms were falsely interpreted as implying that leaders should not lead, but just listen and co-ordinate, Freire famously rejected that formulation. He said: “I am a teacher, not a facilitator”. This has been a crucial theme of my own development. There is no doubt in my mind that Britain as a whole and the societies and cultures where I have worked are deeply authoritarian, to their core. That is still the case today, no matter how carefully or hypocritically it is disguised. In my account of the politics of Staveley and North-east Derbyshire in the late 1960s and early 1970s, written in 1976, I advanced the concept of hierarchical military command structures, arguing that only some such term can make sense of the complex, sometimes convoluted but always underlying nature of authority in British culture and society. It is based on a military model and metaphor, deriving from ages of invasion and oppression by the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings and the Normans. At its core is the feudal model of land tenure and social organisation, from the monarch down to the impoverished base. It still dominates British society today, but its power is (I hope) weakening. It needs to be uprooted and replaced by a process of complete re-orientation and re-thinking. That is made all the more difficult because it is still so deeply embedded in what Pichon-Riviere calls the social unconscious: in popular assumptions about social organisation at every level. We need to re-examine and explore the meaning of authority, starting from the ironic reality that this word is based on a verb meaning to originate, increase and promote. Only by recasting our understanding of the meaning of authority, on the basis that everyone, every single person, has authority, and also that persons are not independent isolates, but exist in relation to each other in families and communities, and at different levels of scale – only on this basis can we find our way out of the maze of authoritarianism, into what I now conceptualise as a fundamentally democratic interpersonal and intergenerational model which also acknowledges the existence of different levels of scale. It must also, and simultaneously, acknowledge the need for good leadership. I am unequivocally in favour of good, strong leadership, a leadership deriving its authority from all of the people themselves, not simply a majority in a one-off election. Such good leadership also derives its authority from good principles, good ideas, good practices, which are orientational. One of the inescapable, existential problems of being human is that we sometimes act unthinkingly on the basis of daft ideas that have got into our heads! The best way of addressing that problem is through ongoing dialogue.

Writers Workshops

In Britain and indeed throughout Europe and the whole world, the words anarchy and anarchism and the phrase mob rule have been used to maintain elite dominance for over two thousand years. They are intentionally deployed in order to rubbish and prevent any “outbreak” of direct democracy, and in Britain’s case to protect and advance the cause of something called representative democracy. I share the view argued by Quintin Hogg, later Lord Hailsham, that what in Britain is called representative democracy is really a form of elective dictatorship. Simultaneously with supporting the work of ALP, I was working for the WEA in south-east Scotland, initially as their only Tutor Organiser. That meant at the start teaching the Basic Shop Stewards and Health and Safety at Work courses that had been created by the TUC. These centralised curricula were aligned with the aims and policies of the then Labour government at Westminster. The WEA at that time had been praised as “so noble an institution” because of its decentralised and participatory structure, praise with which I agreed then and still do now. The District Committee, led by the inspiring and benign Pearl Henderson of Kirkcaldy WEA branch and Fife Labour Party, asked me to develop new approaches to work with unemployed people, and in the field of writers workshops. I did so. Accounts of that work are to be found in Adult Education and the Unemployed and in the middle chapters of Vulgar Eloquence.

Our work with unemployed men and women was based on genuinely participatory research. We had very good collaborative relationships with Lothian Regional Council’s new Community Education Service, at field worker and area officer levels. We asked our colleagues in Com Ed to identify men and women who were unemployed, unskilled or semi-skilled and who had left school at the earliest opportunity with no or very few educational qualifications, from across the whole city of Edinburgh, particularly the large peripheral housing schemes and inner or intermediate city areas. I had been reading Eugene Heimler’s inspiring book Survival in Society. Heimler was a Hungarian Jew and social democrat who had survived Auschwitz and had a personal breakdown as he returned to his native country. He had hoped to resume his political activism, but his country was almost immediately invaded by the Soviet Union which abolished the independent Social Democratic Party. Heimler was forced to flee, making his way to London where he eventually found work as a baker’s assistant, and somehow also finding his way into personal psychoanalysis. He emigrated to Canada where he became a Professor of Social Work. What distinguishes Heimler’s approach to research is that he integrates personal in-depth interviews focusing on his subjects’ whole range of life experiences, views and wishes, with empirical evidence of their circumstances. Using an adaptation of Heimler’s approach, we carried out interviews with 15 men and 16 women, focusing particularly on early and later experiences of family, schooling and upbringing, housing, health and ill-health, work history, accidents, medical treatment, experiences of unemployment, lack of money, depression, drink, TV, fear of life, avoidance of life and other themes that emerged. We also asked them what they wanted to learn and what they were actually interested in. This approach provided us with invaluable breadth and depth of understanding. We embarked on a long-lasting collaboration with Edinburgh University Settlement’s Basic Education team, and designed a programme of learning based on the interview findings. These were published in a pamphlet entitled Some Unemployed Adults and Education.

All of our interviewees were offered a place on the course and the majority accepted. We paid their bus fares and provided free lunches. The programme included Writers and Readers Workshops, Politics and Society Today, Human and Relations, Welfare Rights, and Maths and Arithmetic. When the course came to an end there were follow up courses for the members, and a new intake class also began. The tutors without exception rose to the occasion. Thanks to our colleagues in Com Ed and the great help of Edinburgh Evening News, there was no difficulty in publicity or recruitment over the following years. In 1984 Sally Griffiths and I edited Adult Education and the Unemployed, to which the tutors each contributed a chapter. It sold out 2000 copies throughout the UK. I know that this programme led the way in breaking out of excessive subject specialisation and over-academic approaches: but our tutors all knew their stuff. They were leaders and innovators in their fields. The Unemployed Courses continued to flourish well into the 1990s, long after I had left the WEA.

Writers and Readers Workshops were integral to the Unemployed Programme, but in fact preceded it in time. In the inner city area of Tollcross, there were some poor streets that had not yet been gentrified. We leafleted those and began the Tollcross Writers Workshop just across the road in the dilapidated back room of what was then called the Citizens Rights Office. What this workshop did was to invite and encourage members to write from their own lives. I called this “self-life-writing”, a deliberate translation of the Latinate auto-bio-graphy. There was no attempt to teach members how to write or how to spell, nor in any way to “improve” their writing. The obvious implications were that people’s lives are valuable in themselves; and that what they say for themselves, in their own words, is inherently valuable. The coordinators (there were two of us, a man and a woman) also wrote in their own words, from their own lives, and took their turns to read in the group, which always sat in a circle. This approach, including regular publication of booklets like Clock Work (so-called because of the Toll Clock at the Tollcross) caught on and spread rapidly. In no time there were Writers Workshops in Leith, Wester Hailes, Gorgie Dalry, the East End of Glasgow, in Lanarkshire, in Fife, in Aberdeen and so on. This wave of popular self-life-writing culminated in a series of national gatherings called the Scottish Writers Workshop Come-All-Ye’s, which took place in Newbattle Abbey College in Midlothian. The wave ran on for some years, I think because of the self-life-writing theme, and the orientation of acceptance and affirmation. That commitment became diluted when some workshops began to let it be known that they were aiming to improve people’s writing with a view to publication in competitive outlets.

The political implications of the work we had been doing since 1969 were becoming increasingly clear to me as we went along. I had already begun to write about these and later began to publish in order to communicate what I thought they were. The WEA had always been linked to the labour movement. In Edinburgh, the WEA had had a District Secretary who became Labour Lord Provost, the admirable Jack Kane. One of my predecessors as Tutor Organiser, Robin Cook, had become an outstanding and courageous Labour MP. Things however were moving on from those days. I had observed Labour in power in Saltcoats, in Staveley and other parts of north-east Derbyshire, throughout Glasgow and now in Edinburgh.

Divine Right to Rule

By the time I came to the south-east Scotland job, I saw with increasing clarity that Labour was losing its way, and also that it was struggling with internal divisions which were not being managed through dialogue and bridge-building but by vicious internal warfare. And at the same time it was behaving as if it had the divine right to rule. Some of the underlying attitudinal difficulties were revealed unintentionally by a throwaway remark by the chair of the Edinburgh branch committee of the WEA. This man was also chair of a Labour constituency party, had a very posh English accent and was frightfully courteous. I heard him say to one of his entourage: “Charles, will you do it?” I said: “Why don’t you ask Harry?” And he replied: “Oh, you know, these people…” The expression “these people” which I subsequently heard him use again, in a different context, referred to working-class, less-educated people in low status jobs.

The penny was finally dropping for me.

This attitude to the great mass of ordinary people tied in very closely with the “leave it to us” assumption which Labour MPs, councillors and key activists had promoted for years. And it tied in with the growing centralization of Labour thinking and practice at all levels. Essentially Labour had become a paternalistic, condescending and controlling party, an alternative ruling class to the Tories, kinder, but every bit as dominating. What I did not understand properly at the time was that this was an epiphenomenon, an unconscious message from an underlying conflict about the meaning of democracy which had been going on for over 2000 years. (See for many examples Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Athenian Democracy from the Late Middle Ages to the Contemporary Era (Brill, 2021)).

The Miner’s Strike

I had been a Tutor Organiser for seven years. Ken Logue left his post as District Secretary in the autumn of 1983, and I was appointed to succeed him. At the same time, the build-up to the 1984 miners’ strike was underway. The old paternalistic leader of the NUM had departed, and had been replaced by Arthur Scargill, a firebrand Marxist of the class war type. I was already aware from our years in Staveley of that aspect of Labour movement culture, and was not surprised to see it re-emerge. At this point, after four years of Tory Government under Margaret Thatcher, Labour had still failed to develop an ethical position from which it could take on and stop Thatcherism. They were oscillating between a Roy Jenkins style of social democracy and the 57 varieties of Trotskyism, chanting their slogans. They had lost sight of what used to be called the “good lefts” of democratic socialism, who were increasingly disregarded. The punch-up version of class war was in the ascendant. Scargill refused to ballot his members. Democracy was forgotten.

In Scotland, Jimmy Reid, who by this time had left the Communist Party, came out in public against Scargill’s orientation and strategy. It was well known that the Scottish miners leader, Mick McGahey, opposed Scargill’s approach but was unwilling to say so in public, to maintain unity. The WEA in south-east Scotland had NUM members in Fife, Midlothian and Central Region, and in some areas there was a strong Militant Tendency presence. I was seen as selling out by some by my refusal to support violent action. It seemed to me then and seems to me now that if you are trying to build the good society you have to use good means. While WEA Tutor Organiser I was also informal consultant to ALP. I was heavily involved in the writers workshop movement and the unemployed work. I had been appalled by the failure of the first referendum, in 1979, to achieve a sufficient majority to trigger devolution for Scotland. In the spring of 1980 I joined the all-party Campaign for a Scottish Assembly, and a year later, disgusted by Labour’s directionless swithering, I joined the SNP.

Psychoanalysis and Scottish Society

But there was another battle going on, deeper in my soul, one that I didn’t understand. In spite of all my activity on so many different fronts, I was unhappy in my life. Fortunately, in the autumn of 1979, I took the advice of Gerri’s wise old friend, Janet Hassan, and began a twice a week analysis with Alan Harrow, Director of the Scottish Institute of Human Relations. I went to see Alan for four years. It was one of the best decisions I have ever made. This new engagement in internal and interpersonal reflections on myself, my childhood, my relationships and my work underpinned the long period of creativity from 1979 onwards. As the years went by I became clearer about many of my attitudes and other internal processes. I found an increasing wish to continue to reflect not only on my own, but also in the company of others.

The Scottish Institute of Human Relations had made a very significant contribution to Scottish society from its beginnings at the end of the 1960s. Its main founder John D (Jock) Sutherland and his co-founders located themselves on the cusp of a broad progressive wave sweeping through Scottish society from the late 60s through the 70s, 80s and into the 90s, concerned with the transition from industrial to post-industrial society, the emergence and unification of social work, the creation of the Children’s Panel system and list D schools, the comprehensivisation of primary and secondary schooling, the abolition of corporal punishment, and the expansion of further and higher education. The Institute also took an interest in communities and their development, the optimal development of the welfare state, growing up in Scotland, the psychiatric needs of young people, and the development of adult and community education.

Sutherland had for 20 years led the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations in London, and edited the International Journal of Psychoanalysis. After his retirement and return to Scotland, everything he did was imbued with an awareness of social, economic, cultural and technological questions. He was trying to move psychoanalysis out of the narrow, individualistic model of five times a week therapy, towards social applications in the real world: community psychiatry, counselling, family therapy, organisational consultancy, group relations training and group analysis. For a time it looked as if he would succeed, but in the end the spirit of greed and individualism won out, even though Thatcher herself had already been deposed. Throughout my analysis with Alan Harrow, Sutherland’s spiritual son, I was conscious of seeking to integrate these human relations insights with my interest in Freire and involvement with ALP, the unemployed work and the writers workshop movement. I increasingly came to feel that the ideas of the Trade Union movement, the Labour Party, the Communist Party, and much of academia were intellectually, emotionally and relationally impoverished. They were one-sided. They lived and thought in terms of an empirical understanding of the external world. Many of them knew little of inner and interpersonal worlds.

On leaving the WEA in 1986, I began a two year part-time training in Human Relations and Counselling, run jointly by the Scottish Institute of Human Relations and the Extra-Mural Department of Edinburgh University. This course was created by Mona Macdonald and based on a similar course run by the Westminster Pastoral Foundation in London. Gerri had preceded me on that course by two years. I now earned my contribution to our living by teaching the Community Education core course in the postgraduate masters programme in the University’s Department of Education. I also taught Freirean approaches to education and learning at Northern College’s Dundee and Aberdeen Campuses, and for one year Philosophy of Adult Education at the University of Glasgow. At the same time I trained as a marriage counsellor and gained some insights into bereavement counselling. Six months later I was appointed as half-time research officer on the Scottish Association for Counselling/Scottish Health Education Group project to identify all the counselling and psychotherapy services and trainings throughout Scotland. That produced the two volume Directory of Counselling and Counselling Training Services published in 1989, out of which in turn came the Confederation of Scottish Counselling Agencies, now known as COSCA, of which I served as Convener for four years.

The Human Relations and Counselling Course was led by Mona and taught mostly by Judith Brearley, with contributions from Una Armour and Neville Singh. It was a transformative experience for myself and other students who joined it. It enabled me to further advance my re-orientation. I still taught Freire, Martin Buber and Community Education, but with a growing sense of confidence that outer, inner and interpersonal dimensions had to be regarded as integral to each other. I then began a four year training in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy as a student, which was disappointing in comparison with the Human Relations and Counselling course. Gerri and I had meanwhile been asked to write the story of ALP as a joint project involving Lothian Regional Council, the Scottish Institute of Adult and Continuing Education and the Open University Press, a project chaired by the inspiring Professor Lalage Bown of Glasgow University. The ALP Book as it came to be known was launched to great acclaim in 1989. It outsold Adult Education and the Unemployed worldwide, and was later republished by Sense Publishers in 2011 with an updating chapter by Stan Reeves, Nancy Somerville and Vernon Galloway with a new introduction by Jim Crowther and Ian Martin.

At this point I was still earning my contribution to our living costs through part-time teaching. I was now asked to teach counselling courses in Community Education in Lothian, throughout Scotland by the Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations, and Counselling in Social Work Settings for the Social Work Department in Edinburgh. In these latter projects, I was joined by my friend Judith Fewell, a very able teacher. These years of intensive activity have to be understood against a background of equally dramatic changes in British and Scottish society. Margaret Thatcher, that strident and forceful actor on an ever-widening stage, had been dethroned by a cabal of moderate Tories, and replaced by John Major. The Scottish population hated Thatcher and Major equally, and by 1989 their support for the Labour Party in opinion polls had reached 49%. But Labour still had no idea how to respond to Thatcherite individualism, selfishness and downright greed. Neither Michael Foot, Neil Kinnock nor John Smith could really rise to that challenge, though they saw off the worst excesses of Trotskyism.

Vulgar Eloquence

In 1989, while co-writing the ALP book with Gerri and researching the Counselling Directory, I was approached by my long-time friend, Ronnie Turnbull, co-author with Craig Beveridge of The Eclipse of Scottish Culture and later Scotland After Enlightenment (both Polygon). Ronnie was at that time editor of the Edinburgh Review. Backing Ronnie was Cairns Craig, then Professor of English Literature at the University of Edinburgh who was behind the new Determinations series being published by Polygon, whose general editor was Peter Kravitz, ably supported by Murdo Macdonald. Ronnie announced: Kirkwood must speak (as if I had not been talking enough)! I was encouraged to write the book which became Vulgar Eloquence. From Labour to Liberation: essays on education, community and politics, which was published by Polygon in 1990. It is a collection of almost all my papers and polemics from 1969 until 1989. Each paper is prefaced by an introductory note, setting the scene.

I will say just a few words about Vulgar Eloquence, which had a significant impact and evoked an utterly unexpected response. For the first time in my life my work was fiercely attacked by a whole bevy of reviewers. Peter Kravitz, coincidentally, had just left Polygon (ironically to train as a therapist). I soon found out that his successor had ceased to publicise (and therefore sell) Vulgar Eloquence and had removed it from the Determinations series, of which, like Ronnie and Craig’s books, it was an integral part. I further discovered that a friend of the new editor, who was also involved with Polygon, was rubbishing my approach to research. Another more senior academic, who was simultaneously courting me and Gerri as personal friends, wrote an inaccurate and disparaging review of it which was circulated to all members of faculty in the University of Edinburgh and to some previous graduates.

There was a flurry of such negative reviews. I finally began to put two and two together: these reviews, with one exception, were written by people with links to the Labour Party. I was never again invited to speak at organisations associated with Labour or the trade union movement in Scotland. Some people I knew quite well looked at me strangely and passed by in silence. I had been anathematized. A strange fate for a democratic socialist!

By 1994, a further hostile review had emerged, this time from two writers I knew in Moray House. They announced that I “lacked authority”. This attack emanated from the same quarter as those who had previously branded Paulo Freire’s work as “airy Freire”. At the time, I decided not to reply. However, I am happy to say that these two people have now become enthusiastic supporters of Freirean ideas and practices.

Persons in Relation

That same year I took up the post of Senior Lecturer in Counselling Studies at Moray House College of Education, following in the footsteps of my friend Margaret Jarvie, with whom I had taught the first postgraduate Diploma in Counselling a year or so earlier. For the next ten years, again in collaboration with Judith Fewell, I rewrote and taught the Counselling Studies programme. We decided to ground it in the idea of dialogue between the person-centred approach and psychodynamic perspectives. The person-centred approach was then associated with the work of Carl Rogers and his followers in the USA, and in Britain with Brian Thorne in Norwich and Dave Mearns at Jordanhill in Glasgow. It was during this period that I began to formulate the idea of the persons in relation perspective, a term I borrowed from the work of the Scottish theologian and philosopher John Macmurray, which is linked with the I/Thou thinking of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber and the personalism of Emmanuel Mounier. I argue further in my 2012 book The Persons in Relation Perspective in Counselling, Psychotherapy and Community Adult Learning that similar thinking is to be found in the work of Jock Sutherland, the research and psychotherapeutic practice of John Bowlby (Attachment, Separation and Loss), and in the work of Ian Suttie (The Origins of Love and Hate) and Ronald Fairbairn (Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality). In my teaching I introduced the idea of the primacy of the other, praise of the good other, and loss of the good other. One way out of this kind of loss is the practice of dialogue, sometimes in the context of what I call dialogical relational psychotherapy.

Around the time of taking up the Moray House post, I was approached by SCVO, on behalf of Voluntary Services Shetland, an arm of the Shetland Council of Social Service. I learned that the Shetland counselling services (such as marriage, alcohol and bereavement, Samaritans and Women’s Aid) were in effect required to send their trainee and experienced counsellors to the central belt of Scotland for training. This was extremely expensive and disruptive for the islanders and their organisations. Moray House agreed to send myself and my predecessor, Margaret Jarvie, to Lerwick about ten times a year, where we taught generic counselling skills, and then a postgraduate Diploma in Counselling to a first intake of a dozen students. This instance demonstrated the intense centralization in Scottish society then, and in many parts of Scotland still today. It also generated local trainer capacity in Shetland. This project lasted ten years and beyond. Some of this work reached its fulfilment after I retired from the University of Edinburgh in 2004 following a major operation for bowel cancer, which was successful. I then worked part-time as a psychotherapist with women and girls experiencing severe eating disorders at the Huntercombe Hospital in West Lothian. Aspects of this practice are captured in a paper I wrote jointly with a patient, Anna Other, and the then medical director of the hospital, David Tait (see The role of psychotherapy in the in-patient treatment of a teenage girl with anorexia, in The Persons in Relation Perspective, Sense 2012, already referred to).

Wester Hailes

Gerri had decided to move on from the Adult Learning Project after the publication of the ALP book in 1989. Her place in support of Stan Reeves was taken by Vernon Galloway and Nancy Somerville, who together wrote the updating chapter in the second edition of 2011. Gerri had addressed national events in England and Ireland, and she was keen to try a Freirean approach in a different setting. She applied for and got the post of Assistant Principal (Community Affairs) in Wester Hailes Education Centre, a Community School in a peripheral housing scheme in south Edinburgh. By this time many good Labour people, in the absence of any meaningful re-orientation within the Labour Party, had resigned themselves to a posture of oppositional hostility to the Tories. Some organisations which had previously been full of hope and a sense of possibility were now reduced to competing for financial handouts from any state agency which offered them. A class of leaders who had become experts in such scavenging had, of necessity, emerged. WHEC was fighting for its life as a locality-based Secondary School, and some of the teachers wanted to offload the community dimension as a diversion of resources from that objective: a short-sighted view, in my opinion. Gerri’s hopes were blocked and after a few years she decided to revive her English language teaching skills. For the next twenty years Gerri took great delight in teaching English to adult students from Hungary to Japan, Italy to Spain, on a homestay basis.

As a man and as a father I had always been struck, and puzzled, by a significant contradiction. Most of the writers I admired were men, with exceptions such as Melanie Klein, Margaret Mahler and Susie Orbach. But much of what I had learned during my life had been through working with women: my wife Gerri, Janet Hassan, Irene Graham, Mary Miller, Mona Macdonald, Judith Brearley, Una Armour, Lalage Bown, Judith Fewell, Margaret Jarvie, Jo Burns and Siobhan Canavan. It was almost as if the men had to puzzle out these ideas through reading and writing them down, like me, whereas the women knew them experientially and intuitively. That may not be a completely satisfactory explanation, but it feels at least partly true. While working part-time at Huntercombe Hospital, and working at home with Gerri to support Anna and her kids, I had my second experience of being a house-husband (the first having been with our own kids in Castlemilk in the1970s).

***

I am going to stop this process of review and reflection now, and complete this paper with a summary of conclusions I have come to over our fifty years of experience and action. I hope it will be clear to you that I reject the Leninist, Trotskyist, Stalinist and Maoist perspectives and practices, essentially because they use bad means to achieve what they believe to be good ends. I reject also their notion that socialism is to be achieved by seizing and using state power coercively. I continue to regard myself as both a democratic socialist and a social democrat. I also admire some aspects of the communitarian liberal and moderate conservative traditions, and endorse the internationalist version of Scottish nationalism. But I reject party politics as inherently divisive: invariably it consists of attempts by small elites to gain power and resources for themselves. The Tory/Labour system in British politics is an example. Paulo Freire’s ideas and methods, while not perfect (nothing human is perfect), are the best integrative model I have found, involving dialogue, communication and bridge-building, not monologue and imposition.

PROPOSITIONS TOWARDS A GOOD SOCIETY

At a global level, life and the earth itself now suffer from the dominance of libertarian-celebrity-consumer-culture, and various versions of capitalism, motivated invariably by greed and the will to power. The so-called United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is not a true democracy and never has been. It is an elective dictatorship based and centralised in London. It consists of two chambers, the House of Commons and the unelected House of Lords.

It claims to have devolved some powers to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. But these acts can be undone at any time by new acts of the centralised chambers. As Enoch Powell succinctly put it: power devolved is power retained. This entire centralised apparatus is grounded in the notion of the crown-in-parliament. That is not some quaint piece of window-dressing, but serves to express the continued sovereignty over the land, sea and people of the UK by the monarch, on the basis of feudal landownership and other feudal rights. In reality, we are not citizens: we are subjects.

All of this must go, and be replaced by processes of fundamental democratisation, irreversible decentralisation and full self-government throughout the communities, nations and regions, right down to the level of citizens. In sum, I favour:

- complete abolition of the monarchy

- complete abolition of all feudal titles, ranks, land and property tenure and all other feudal rights

- establishment of democracy, as an integration of direct and representative democracy at each and every level of scale.

- all power derives from the people as citizens and persons in community, and from the world itself

- complete abolition of the Westminster system

- abolition of the cabinet system: all leadership to be open and transparent

- complete abolition of all political parties

- all government, at every level of scale, to be based on proportional representation

- radical decentralisation throughout the present UK down to levels of scale chosen by direct popular vote, eg Scotland, Wales, England, North-east, North-west, and so on

- the term “state” to be replaced by the term “organised communities” at every level

- within the first level of decentralisation , a second level of decentralisation to a smaller level of scale, for example in Scotland a level such as Shetland, or Borders, and so on

- at each decentralised level, a direct right of assembly, deliberation, participation, decision making, and proportional voting for leaders

- the rights of initiative, assembly, deliberation, participation and to elect leaders go right down to the most local level. It is vital that the reality of local and community self-government and initiative be re-established

In general, an integration of bottom up, top down and horizontal communication principles and practices is required so that there is both a recognition of the need for good, strong leadership and the need for direct initiative and popular participation at every level of scale. To accompany and serve this democratic participatory system, banking and all financial services to be completely reorganised to match and service these levels. The central bank at the old UK level will not exist, but there will be a co-ordinating bank or banks, based for example in Manchester or Newcastle upon Tyne. Through it, banks will have a system of cross-region-and-level coordination in order to create mutual support between the different regions and localities and prevent or reverse inequalities developing. All existing banks and financial services in the private and public sectors to be wholly absorbed into this new system.

The armed forces will be completely reorientated and reconstructed to ensure loyalty to the people and the organised communities at all levels. Reduction of the size of the professional component of the armed forces to be accompanied by the right and requirement for all adults over the age of 16 to serve regularly and recurrently in the armed forces throughout their lives, until an age to be determined (eg 65). A democratic system of election of officers will be developed.

Media and advertising. Abolition of all present privately and publicly owned media, to be replaced by newly created pluralist and decentralised media at levels (1) and (2) of the new system of self-government. There will also be a vital third level (3) of media at the most local level. Rights of direct participation of all citizens and young people to be established at all three levels. Community not coercive editorial policy: all points of view can be expressed and replied to.

Rights, responsibilities and resourcing of all persons/citizens and children.

Rights, responsibilities and resourcing (the three “r’s”) to be integrated. No rights without responsibilities. No responsibilities without rights. No rights or responsibilities without resources. More work is needed here on the outworking of these principles in the relations between women, men and children, between the generations, and between human beings and the rest of the world. Citizens and children are seen as persons in community, persons in relation, persons in society and world at all levels. The three “r’s” to be established throughout life:

- to recognition, appreciation, affirmation and constructive feedback

- to work and a decent income: none of these rights can be derogated

- to decent housing, clothing, furniture and equipment in order to be able to participate fully in culture, society and government

- to study, to learn, to acquire new knowledge and new skills and to do research throughout life: equal support and resourcing for all irrespective of earlier levels of achievement

- to direct participation in sports and healthy exercise

- to adventure, travel, holidays and creativity

- to health and support when ill, equally available to all: no private sector in health

- to various forms of family, community and religion, and open communication and pluralism assumed

General principles and values:

- the flourishing of each and all as best they can, and support for each and all in that aim

- unequivocal discouragement of the “success” principle, and of destructive competition

- work and income: everyone is expected to work and contribute on all fronts as best they can. To work is a right, a responsibility and a privilege. All work is to be equally valued

- the ratio of the highest to the lowest income never to exceed an agreed proportion, eg 3:2, when all net income is taken into account, and in every field of endeavour

- ends and means: as a general principle, good ends cannot be achieved by bad means

- leadership, membership and authority: all of these are vital, based on vision, moral principle, commitment and ability

- leaders should be supported and trusted but can be recalled and replaced by members when it is necessary

- membership is also a vital responsibility and task. Members just as much as leaders have authority and initiative in all sorts of ways

- there is a general opposition to and avoidance of violence, but there is an understanding that there are times in human affairs when the use of violence is necessary, after all other avenues have been tried. In such circumstances, it needs to be socially agreed and justified, in public, and with the right of dissent maintained.

- our highest value, our highest hope and our aim is always for peace, and the flourishing of each and all.

Notes

Colin Kirkwood was Area Principal for Adult Education in North-east Derbyshire, a community activist in Glasgow, Tutor Organiser and later District Secretary with the Workers Educational Association (WEA) in South-east Scotland, Lecturer in Community Education and Senior Lecturer in Counselling Studies at the University of Edinburgh, and Senior Psychotherapist with Women and Girls suffering from severe eating disorders. He is a poet, researcher and author of five books on community adult learning, counselling, culture and society, and a loving husband, father and grandfather.

Gerri Kirkwood taught English to students from all round the world. She was Reporter to Children’s Panels in Glasgow, a community activist in Glasgow and Edinburgh, and for ten years a Community Adult Educator on the renowned Adult Learning Project (ALP) in Gorgie Dalry. She is a loving mother and grandmother with troops of friends, and author with Colin of Living Adult Education: Freire in Scotland.

Accounts of our work, descriptive, appreciative and critical, have already been written over the years and are available in various publications. The key books are Adult Education and the Unemployed (WEA 1984), Living Adult Education: Freire in Scotland (First edition Open University Press 1989, second edition Sense Publishers 2011), Directory of Counselling and Counselling Training Services in Scotland, (Scottish Health Education Group, and Scottish Association for Counselling 1989), Vulgar Eloquence: From Labour to Liberation. Essays on Education, Community and Politics (Polygon 1990), The Development of Counselling in Shetland: a Study of Counselling in Society (COSCA and BAC 2000), The Persons in Relation Perspective in Counselling, Psychotherapy and Community Adult Learning (Sense Publishers 2012), From Boy to Man: Poems by Colin Kirkwood (Word Power Books 2015), and Community Work and Adult Education in Staveley, North-East Derbyshire, 1969-1972 (Brill | Sense 2020).

Alongside these books are the vehicles of what Tim Norton has called community and creativity, including issues of the newspapers Staveley Now, Barrowfield News, Castlemilk Today, Scottish Tenant, and the many writers workshop booklets flowering across Scotland in the 1980s and 1990s.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

Paulo Freire’s humanism – the Marxian idea that it’s through self-experience in the world (‘work’) that we become what we are and the world becomes what it is; that neither is ‘given in nature’ – had a formative influence on my practice in community development too. I was particularly taken by his text, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, in which he sought to deconstruct the passive and often oppressive nature of learning (‘work’) and reconstruct it as a means of building a critical consciousness that would enable people to create change in their lives. My activism was premised on the mantra that ‘There’s no such thing as neutral learning (‘work’). Learning (‘work’) either functions as an instrument to bring about conformity or freedom.’

In common with other critical theorists of the time, Freire observed and deplored what he called a ‘culture of silence’ among the public. He recognised that their disempowerment – their passivity or lack of agency – was a direct result of a system of learning (‘work’) that cultivated that passivity. Freire went on to work in the state learning system itself, where he began by develop adult literacy programmes to help illiterate people to read and write on the rationale that literacy empowered people to participate in society, setting them free from the mindset that they could not alter their circumstances. Acquiring literacy is the first step in the development of a new construction of selfhood that allows people to look critically at the societal and political structures around them. Freire worked within the state learning system to create schools in which questioning the dominant reality ‘is not a sin’.

Freire criticised what he called the ‘banking model’ of pedagogy/community development, in which the master or ‘teacher’ is the all-knowing expert who bestows their superior knowledge on the empty-vessel disciple of ‘pupil’. Freire argued that this approach dehumanises and oppresses the disciple, hindering the development of critical awareness. Pedagogy/community development should challenge learners (‘workers’) to question and examine the dominant power structures and patterns of inequality that shape the world as ‘given’ in our prevailing knowledge and other social institutions.

In place of the banking model, Freire proposed a dialectical approach to learning (‘work’) in which learners (‘workers’) become active agents in their own learning. When education is used as a form of self-development, rather than a memory test or the acquisition of competencies, it becomes a means of self-empowerment.

Freire sought to replace knowledge- and competency-based education with critical- or problem-based systems of learning, which enable learners (‘workers’) to critically engage with the world around them. In contrast to traditional hierarchical power structures between teacher and pupil, the teacher is repositioned within such democratic and cooperative systems to learn as much from the pupil about her/his worlds and experiences (the pupil’s expertise) as much as the pupil can learn from the expertise of the teacher.

Freire’s pedagogy/community development envisions learning (‘work’) as a transformative, emancipatory process through which the pupils and teachers can explore how they might impact and transform both themselves and the world around them in ways that are an expression of the general will of society rather than of dominant interests within that society; social transformation evolving democratically from the bottom up rather than imposed authoritatively from the top down.

Inspiring stuff! All our civic projects, from community education to nation=building, would benefit from being informed by Freire’s work

I, too, have been influenced by the theory and practice developed by Freire and others.

Much of the implementation of Freirian approaches has been in adult and community education and I fully support that. However, before they are involved in adult education (and to a substantial degree community education) everyone in Scotland has had a minimum of 11 years of school education and, increasingly, up to two years of nursery education. In Scotland, 95% of children and young people go to local authority schools. So, the ideas of contientisation and so on have to be utilised there. And, I would argue, that over the years, despite the various hurdles these ideas have been utilised to varying degrees. It is arguable the Curriculum for Excellence has such principles inherent in it.

For many of us the Scottish state school system has been successful in opening our eyes and enabling us to ‘reflect on our conditions’. For others, too, including a fair number of my contemporaries at school in the 1950s/60s, when corporal punishment was in full swing and selection was denying the full breadth of the curriculum to 65% of the population the school experience was not a good one. Yet many of those deemed ‘failures’ went on via trades, FE, trade unions etc, went on to find a richer educational experience later in life. And, from the 1970s, with the advent of comprehensive secondary schools, all young people were increasingly given experience of curricular breadth. The success of examinations like Standard Grade indicated how much ‘ability’ there is within the population. The sneers of ‘dumbing down’ were an indication of the fears of the middle and upper classes that the hoi polloi might actually start invading the professions to which they and their children aspired.

Now, having worked for 39 years as a teacher in the local school system and eventually reaching the status of Head Teacher, I know, only too well that the system had failings and some serious ones. But, it is the system we have and, while, of course, there should be more investment, particularly in early years, there is a great deal of economic, cultural and social capital invested in it and we really have to hold on to that.

We need to make stronger links with adult and community education, with FE and HE. We have good models – such as that at Wester Hailes, to which Mr Kirkwood refers – with which to counter the ‘failing schools’ narrative which pours from the media and, sadly, from sections of the teacher unions and self-proclaimed ‘radicals’ and self proclaimed ‘educationists’ in The Ferret. Since the latter get a lot of publicity in The Herald, they are on the wrong side of the debate.

I should like to thank Mr Kirkwood and his co-writer and life partner for what was a thorough synopsis of their lives over 50 years. I was moved and uplifted.

Can you clarify this for me?

“right and requirement for all adults over the age of 16 to serve regularly and recurrently in the armed forces throughout their lives”

The word “requirement” here seems to suggest that you are calling for the introduction of conscription. If so, I am very disappointed, because I was with you until that point.

Thanks Alastair for this very focussed question. My general attitude to society is in marked contrast to what I suppose I would call capitalist libertarianism, in which freedom means the right to succeed or fail (in their terms), and go the wall if you fail. To me, society is that of which we are a part by virtue of having been born. We are persons in relation, persons in community, persons in society. The basic assumption is that we join in, take part and contribute as we are able: and we have rights, responsibilities and resources. That applies also in the field of defence against attack. I am not in favour of large, so-called professional armed forces, which are historically linked with feudalism and in this country certainly, the farce of royalty and the centralisation of power I am in favour of a society in which everyone is held to be of equal worth: equality of regard as Gordon Brown once called it. That means we must reconceive the armed forces and defence, a process in which I assume everyone will be involved. That ‘s not conscription, which is a form of state coercion. It assumes communitarian engagement and involvement.