Dom Phillips – The Subterranean

Neil Cooper remembers the journalist Dom Phillips, who has been killed with the activist Bruno Pereira in Brazil (‘Bruno Pereira highlighted the ravaging of the rainforest and abuse of human rights. Dom told his story. We should honour them‘).

“Justify yourself! Go on. Justify yourself…”

These are the words I associate most with Dom Phillips, the investigative reporter who disappeared on June 5th in a remote part of the western Amazon. Phillips was travelling with indigenous advocate and guide Bruno Pereira while researching a book about sustainable development in a region where criminal activity at the expense of both the environment and the Indigenous population is paramount.

The disappearance of the two men and the seemingly lacklustre initial response from the Brazilian government caused international outrage. A tireless search by the Indigenous community working with police has seen two fishermen arrested, with the inquiry reclassed as homicide. One of the fishermen has confessed to murder, and two bodies have been found. Whatever happens next, some hard questions need to be asked, about how such a tragedy happened, and why it was allowed to happen. But who will be doing the asking?

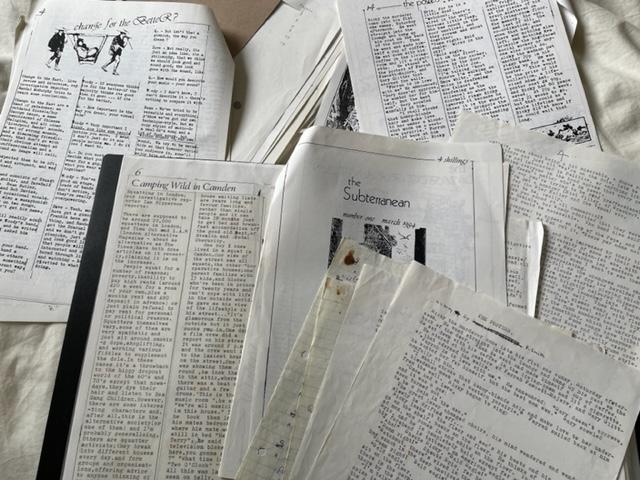

Dom Phillips’s demand for others to explain themselves quoted at the top of the page stood out during the short time I knew him in Liverpool during 1983 and 1984. It became a self-mocking catchphrase of sorts, whether in everyday discussions or while interviewing uppity Liverpool bands. The latter was for The Subterranean, the short lived fanzine we put together during that time, and which contains what were probably Dom’s earliest published works before he went on to far greater glory.

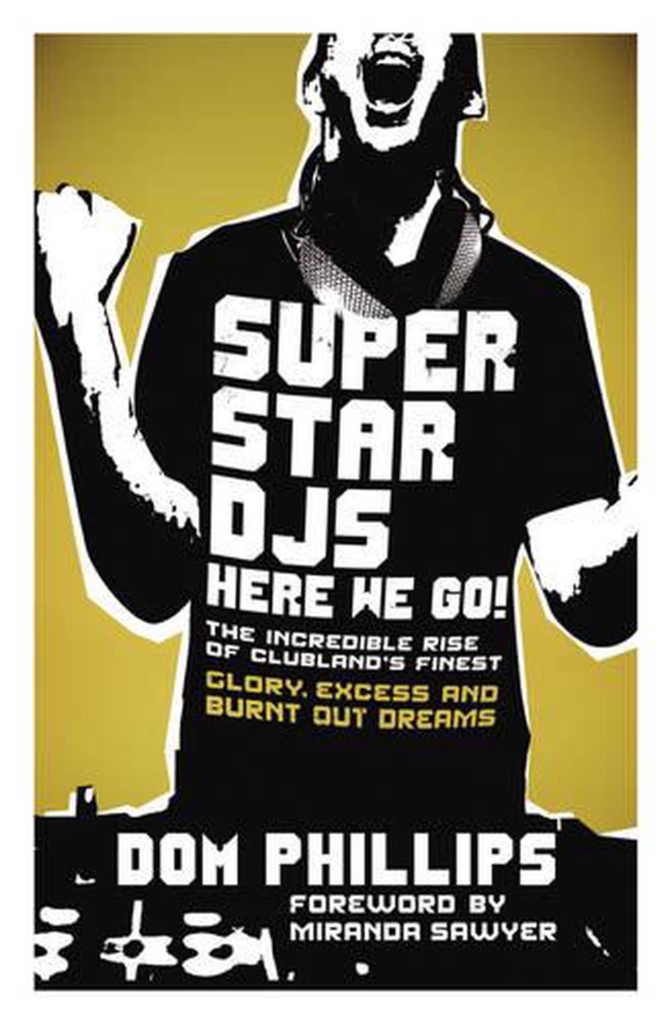

This came first during his stint as editor of Mixmag during an era that fed into his frontline history of 1990s club culture, Superstar DJs Here We Go!: The Rise of the Superstar DJ, published in 2009. This was followed by his fearless dispatches on environmental and political issues in Brazil published in The Guardian, The Washington Post and other outlets. Reading all these over the years from a distance, Dom’s mantra never seemed far away.

Dom was never bolshie when he challenged people with awkward questions in an attempt to push them beyond their surface bluster. While deadly serious in his attempt to get to the heart of the matter, his eyes widening with passionate intensity as he gesticulated with open hands, as far as uppity Liverpool bands were concerned, at least, there was a sense of mischief to his eternal inquisitiveness. If he spoke his mind, it was only to get to the truth.

I’d met Dom indirectly by way of Candy Opera, a band I knew from a couple of years earlier. They in turn had met another band, called Perfect Day, whose singer John was mates with Dom. Both Dom and I had seemingly muttered similar thoughts out loud about wanting to start a fanzine, so it seemed logical to whoever it was that picked up on this to shove us together.

John was at college in Liverpool, and he, Dom and another mate, Fitz, moved from the Wirral on the other side of the Mersey into a flat on Huntley Road, Liverpool 6, a short walk from where I was living with my mum. Dom’s younger sister Sian was around as well, and for a few short months, the Huntley Road flat became a bit of a hang out place. It was also the editorial address for The Subterranean. Everyone living in or around the flat contributed to it at some point. It was that kind of place, where late nights were soundtracked by the Modern Jazz Quartet and John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, two of Dom’s favourites.

Dom was steeped in the jazz romance of the Beats, and he adored Jack Kerouac. This was evident in his insistence we name our zine in honour of his favourite Kerouac book, The Subterraneans. This semi-fictional novella charts a short-lived love affair between the book’s narrator Leo Percepied and an African American woman, Mardou Fox, as they freewheel their way through Greenwich Village basement bars before they fall apart.

The subterraneans of the title were the coterie of drug and drink addled would be writers, artists, bohemians, poets, intellectuals, drifters, dreamers and hipsters in the original sense of the word with whom Leo hung out. It was a world Dom was instinctively attracted to, and he quoted the book’s heartbreaking last line often. ‘And I go home having lost her love,’ it went. ‘And write this book.’

Dom’s work gave The Subterranean its heart. The quality of his writing went beyond the first and only issue’s mess of wonkily placed images, Spray Mount stained Letraset headlines and misspelt missives typed out beside them. In the pre internet age, this was how it was done. Even better that it was all resourced on the fly by the print unit of the civil service department where I was an office boy.

Dom passed over his contributions in a clear plastic folder containing five items held together with a paper clip. Most were typed out on a machine clearly in need of a fresh ribbon, and with various crossings out punctuating the text. One piece was handwritten in biro. What on earth was I supposed to do with all that?

The Subterranean led with two interviews by Dom, one with Candy Opera, and the other with a group called Change to the East. He put both bands on the spot, not letting either think all they were doing was playing pop songs. A short story, The Posters, told of a disturbed middle aged man who lived alone on the dole and spoke only to his posters of Farah Fawcett-Majors and Gary Glitter. The by-line of ‘Dominic Phillips’ on the original manuscript had been crossed out, and the story was credited to P. Smith.

As Kurt Spelvegels, Dom wrote and drew a cartoon strip, High Tech and Low Life! This was a comic one-liner riff on the class divide that cast a depressed looking dole queue veteran and an NME reading hipster as a kind of existential Odd Couple for the 1980s. It was intended to be a regular series.

If all this wasn’t eclectic enough, Dom wrote a piece called Camping Wild in Camden. Credited to Ian Hipperson, this was a first hand look at the squatting culture he experienced while on his travels in London. Like everything Dom did later, the article combined the personal and the factual, taking a stance as he went. His style drew from American New Journalism, but without its gonzo excesses. He may have only been 19, but Dom was already an explorer, hungry for experience and alive to the possibilities he was documenting.

Why everything in The Subterranean was published under pseudonyms I don’t know. Two of Dom’s other nom-de-plumes were Randall McMurphy and Waldo Jeffries. The first was taken from the anti establishment psychiatric patient in Ken Kesey’s novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, played with mercurial bravura by Jack Nicholson in Milos Forman’s film version.

The second was a possible mishear on the lovesick lead character in Lou Reed’s macabre short story, The Gift, performed by John Cale on The Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat album. In the story, Waldo posts himself to his long distance girlfriend, only to fall foul of his elaborate gift wrapping. Both of Dom’s aliases said much about where he was coming from.

This was made even clearer when we went to see Allen Ginsberg, who was appearing at the Neptune Theatre in Liverpool. Here was a real life Beat poet in our midst, one of the holy trinity who came up alongside Kerouac and Burroughs, and the man who in 1965 had declared Liverpool to be ‘at the present moment, the centre of the consciousness of the creative universe’. Now here he was making a prodigal’s return, and Liverpool scenes old and new turned out to pay homage.

We spotted the somewhat professorial looking Ginsberg sitting at a table with Liverpool poet Adrian Henri in the bar before the show. We’d brought a tape recorder along in the hope of getting an interview, and now here he was, just a few feet away. It was too good an opportunity to miss. Steeling ourselves, we approached the great seer to see if we could meet him after the show for an interview.

“Do it now, “ Ginsberg instructed, seizing the moment. We hadn’t prepared anything, but sat down anyway. I can’t remember what we asked, but through our bumbling, it gradually dawned on us we’d gatecrashed an interview already in progress. Earwigging in on this proper journalist’s questions, it was clear he’d done his homework a lot more than we had.

Perhaps to be kind, Ginsberg started asking us about poetry, and before departing to prepare for the show, sagely told us how everyone in Liverpool should read Rimbaud.

Dom watched Ginsberg walk away. “I only wanted to ask him if it was true he really took all those drugs,” he grinned.

Superstar DJs Here We Go! briefly looks at pre rave era Liverpool, when it was a broken but defiant city of chronic unemployment and militant political unrest. Dom writes of attending a rally at the town hall when the city’s entire workforce went on strike, as the City Council prepared to confront Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, then in its post inner city riots, post Falklands War, second term.

At the town hall, council deputy leader Derek Hatton held court from the balcony, flanked by his comrades like a politburo in waiting. With 50,000 people in attendance, as a show of strength, it was a mighty looking spectacle.

Dom and I went to the rally together, though I probably had more faith in the rabble-rousing polemic than he did. Afterwards, we went on an all day bender, that took us from a Mathew Street pub, to an afternoon drinking club on Bold Street, eventually ending up at the cheap drinks student night at The State ballroom on Dale Street. This was clearly how subterraneans were meant to live.

By this time, we had photocopied a couple of hundred copies of our funny looking, badly spelt little zine. We spent the next few weeks selling them around gigs we blagged our way into, or else setting up interviews with anyone that moved. There were more bands, including an interview Dom did with one of A Flock of Seagulls, who was a mate of someone I knew at work. Again, Dom challenged him in a good natured way to justify the band’s existence beyond being a chart friendly pop group. An interview with Dom wasn’t so much a cosy chat as a pop cultural summit.

There was a sit-down with a couple of Brookside actors, and Dom spoke with Harold Salisbury, an old jazz saxophonist from Preston, whose band, Free Parking, played at the Philharmonic Pub on Tuesday nights. We also saw them one night at Chauffer’s, a late night dive at the other end of Hope Street. Salisbury was probably not long out of his 40s, but for a pair of young wannabes high on the mythology of poetry and jazz, he seemed ancient. To have someone as wizened as Ginsberg and co pretty much on our doorstep was something to relish.

Some of this was set to appear in the second issue of The Subterranean, which, as with the first, was laboriously laid out with the aid of Letraset and Spray Mount, but it never happened. Dom moved to Rome, to Bristol and beyond, at the centre of the dance music revolution that became known as Rave, before charting unknown territories that eventually led him to settle in Brazil.

Almost four decades on from The Subterranean, Dom Phillips remained as fearless and as forensic in his lines of inquiry as he had been back in Huntley Road. He still took a stance, still asking the difficult questions, imploring those he questioned to justify themselves. It wasn’t uppity Liverpool bands he was asking anymore, but right wing presidents seemingly happy to leave Brazil’s Indigenous population to the mercy of gangsters. From such a morass of high-end criminality and environmental destruction, the book Dom Phillips was working on was set to be called How to Save the Amazon. It might have changed the world. It may yet.

Whoever picks up the mantle of Dom Phillips needs to be just as fearless in their approach. If ever there was anyone who should be forced to justify themselves, it is those culpable in his and Bruno Pereira’s disappearance and murder at both a political and criminal level. In the meantime, the world just lost two of the finest minds of their generation. Justify that.

A crowdfunding campaign has been launched to support the families of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira. Donate here in English – https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-dombruno-missing-in-the-amazon-rainforest, and here in Portuguese – https://www.vakinha.com.br/vaquinha/unidos-por-dom-e-bruno

A truly tragic story, and a great man gone too soon. However, I can’t help but add Truman Capote’s description of On the Road – “That’s not writing, that’s typing.” RIP Dom.

Good morning, Neil. I am the obituaries editor of The Australian, the national daily newspaper. I am a former long-time journalist in The Times and Sunday Times. I thought your words on Dom Phillips were lovely and, even though I never met him, I feel I know the sort of man he was after reading them. I will write an obit on Mr Phillips for the weekend. I was planning on quoting a few lines of your (attributing them to you, of course). I wonder what you know of his time in Australia, what he did, where he lived, and with whom. And, if you’d like to add anything else, feel free. I was bouncing around England in those days of The Subterranean, but my tastes were more conservative, although we did follow The Monochrome Set around for a while, but moved on to IQ, Marillion and Echo and The Bunnymen! Best wishes to you as you, and Mr Phillips’ other friends and family cope with the dreadful events of this month.

Alan Howe

Hi Alan,

Thank you for your comments. It’s really appreciated.

I can’t be much help, though, I’m afraid.

I hadn’t seen Dom since the period described in my piece, and wasn’t aware he spent any time in Australia.

If I think of anything I’ll let you know, but I suspect his colleagues at the Guardian will be able to advise better than I.

I look forward to reading what you write.

And please feel free to quote from my piece.

Thanks again.

Bests.

Neil

Thanks. Loved these insights and anecdotes.