Sandra George: A Life in Pictures – Craigmillar Now and Then

A retrospective on the life and work of Sandra George whose work ‘Sandra George : Craigmillar 1988-1994’ runs at The White House, 70 Niddrie Mains Road, Craigmillar, Edinburgh until September 12th. An online version of the exhibition can be seen at www.craigmillarnow.com.

The White House

Sandra George’s presence can be felt everywhere in Craigmillar just now. The legacy of the Edinburgh based photographer and community educationalist who died in 2013 aged 56 can primarily be seen at The White House, the B-listed Art Deco former pub on Craigmillar’s Niddrie Mains Road that is now an airy community cafe. Here, the walls are adorned with twenty photographs by George that form a new exhibition showcasing a handful of George’s works taken in Craigmillar between 1988 and 1994.

The White House is the perfect location for George’s black and white images, brim full as they are with the life of a community at work, rest and play. In one, kids eye-up the local policewoman from the safety of the school gate. In another, women keep their heads down, intent on a win at the bingo. Mums with push chairs take a breather outside the Outreach Café. An instructor on a pigeon-keeping project gently places a bird into a young boy’s hands while two girls look on. The vibrancy that shines through comes from a clear empathy between George and those in her pictures, who aren’t so much subjects as participants, rising to the occasion with roaring everyday life.

George’s images of children are especially powerful. Several of these are taken at Niddrie Adventure Playground. In one, a little girl swings from a ‘flying fox’ towards the camera. In another, four wee guys line up like would-be tough guys, while another kid casts a glance at them as he walks past. Another catches the rough and tumble of a drama class, as three boys adorned with face paint play fight. There is even a photograph of George’s son, Tyler George Hewitt, himself then a child, seen through the glass of a bus stop.

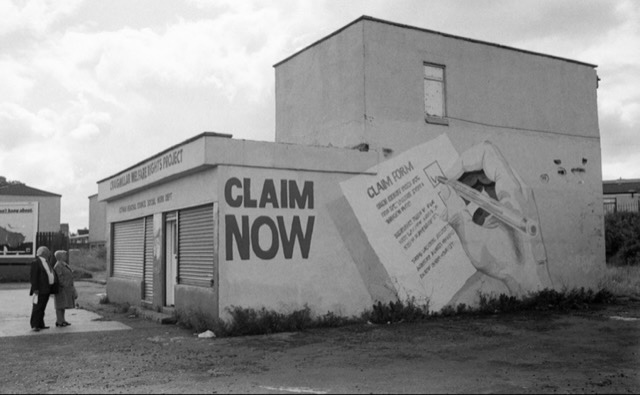

One image sees an elderly couple standing outside the old Craigmillar Welfare Rights Project building. Though the shutters of the building are down, its sidewall is emblazoned with a mural. Painted by artists Mike Greenlaw and Angus Meechan, the mural depicts the words ‘CLAIM NOW’ in bold letters beside an image of a hand ticking a box on a claim form.

This Paris ’68 style slogan-based living newspaper writ large sets the power of the people in stone as a how-to guide to liberation. It was this same sense of people power that gave Sandra George the drive behind her work, as well as its heart and soul.

Craigmillar Now

The roots of Sandra George’s exhibition can be found a short bus ride up the road from The White House, at Craigmillar Now, the local arts and heritage centre based in a former church building on Newcraighall Road, just across from Fort Kinnaird Retail Park. The old church was once where Craigmillar Festival Society called home. The link is significant. CFS, founded in 1962 by a group of local mothers led by the late Helen Crummy looking for music lessons for their children, was a pioneer in community arts throughout the 1970s and 1980s, with its work recognised around the world. A statue of Crummy by Tim Chalk sits outside the East Neighbourhood Centre and Craigmillar Library on Niddrie Mains Road, a short walk from The White House on the other side of the street.

Craigmillar Now, founded in 2020, has picked up Craigmillar Festival Society’s baton. In its short existence, it has already presented exhibitions by Syrian artist Nihad Al Turk, and a residency by Ugandan artist Barbara Byahurwa. Both artists live locally. Among a variety of projects, the organisation has also formed an archive group, with the long-term aim of archiving Craigmillar’s past, while keeping its eyes firmly on the future.

Both strands of George’s work forms something of a continuum between Craigmillar Festival Society and Craigmillar Now. Her photographs also document an Edinburgh in the throes of social change, when Craigmillar and other areas built on the outskirts of the city were riven by social problems and a lack of local resources.

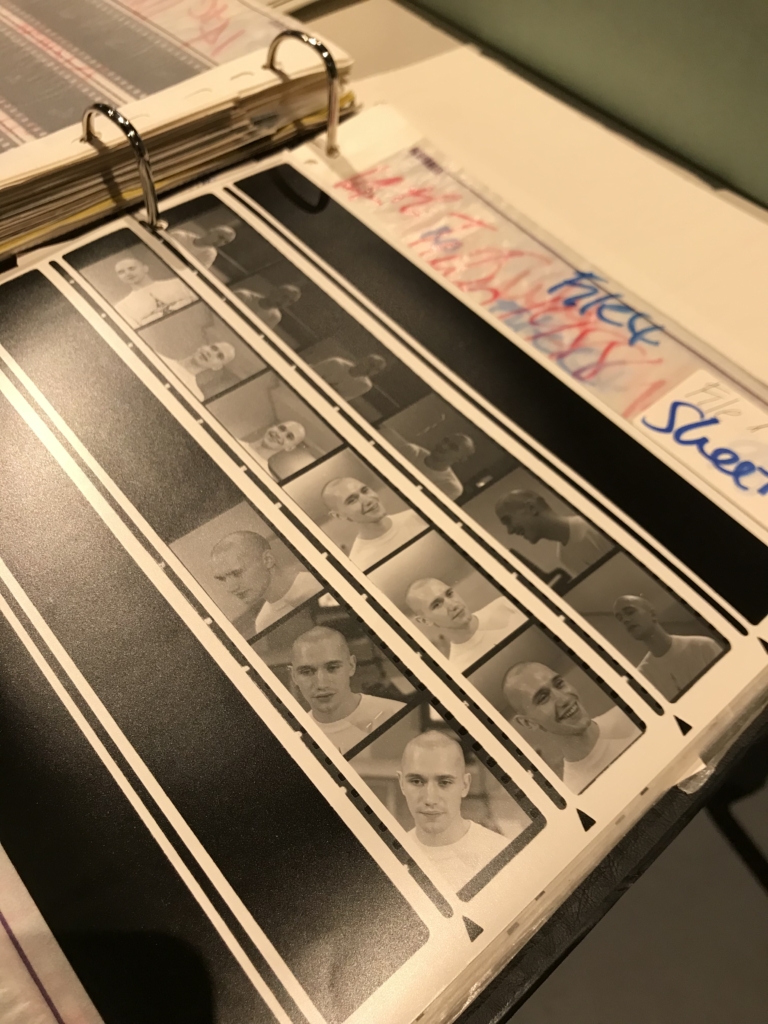

The boxes of several thousand negatives of George’s photographs donated to Craigmillar Now by her former partner Jimmy Hewitt and their son, Tyler Hewitt, are testament to this. As too are the shelves of George’s books lining the upstairs wall of the small open plan office Craigmillar Now Project Manager Rachael Cloughton shares with two other part time staff. Row on row of art and photography books nestle next to volumes of political history and philosophy. Books on Africa take up the whole of one shelf. A biography of Martin Luther King sits on another.

Downstairs, the boxes of negatives are laid out on a table in the former church’s main hall, where the archive group are going over George’s work with a meticulous eye. After selecting the twenty photographs for the current exhibition, the long-term aim is to preserve and digitise each and every image. The process has clearly become a labour of love for all involved. For Jimmy and Tyler, such attention is long overdue, even though they know it might not necessarily have been welcomed by Sandra.

“There was always a point of contention between me and my mother,” says Tyler, sitting beside his father at a trestle table in Craigmillar Now, with the boxes of Sandra’s negatives close by. “She’d go off and do this work, and she’d put in hours above any wage she was receiving, because she was always so committed to what she was doing. So to see the number of people who are coming in to the exhibition just now and hearing about how great she was, it’s kind of like, yeah, she was pretty awesome.”

Jimmy is “absolutely over the moon Sandra is getting recognition in this way. But I think when she was alive as well, she got so much respect and recognition from the people that she worked with, and that was what counted for her. After her degree show, she never had another exhibition, but that wasn’t what she was after. She wasn’t wanting that kind of recognition. She preferred to get the recognition for the good work she was already doing.”

As Tyler puts it, “She was much more committed to the ideals and goals of the projects that she created than anything else. She was willing to go above and beyond whatever she was working on, whether it was spending more time, or spending a little bit more money to get resources for projects. She felt something could be done by her to get from where she was to a project’s goal, and she would do it, then try and make everything balance to some degree after the fact. And if it was still balanced more in favour of the project than herself, then so be it.”

A Living Archive

While the White House exhibition is a surface-scratching taster of George’s huge output, that her archive has come to light at all is a happy accident. After Sandra’s death, Jimmy and Tyler came across around half a dozen large boxes of her negatives and contact sheets of images dating all the way back to her student days.

“Just about every photograph she’d ever taken,” says Jimmy, “she kept the negative and contact sheet. We didn’t know what to do with them. We didn’t have the resources to organise anything, so they ended up in my garden shed.”

Fast forward to November 2020, and the newly opened Craigmillar Now is hosting its first ever archive section. City of Edinburgh’s community payback team is also in regular attendance, clearing the garden around the building. As manager of the team, it was Jimmy’s job to check in to make sure all was going as planned. It was then he stumbled on the archiving session.

“It was a fluke that I came here to the Art Centre and met Rachael,” he says. “We got talking about the centre, and how it had been refurbished, and she asked me had I been here before. I said, yeah, my late partner used to work here, Sandra George.”

Sandra’s name was already legend in Craigmillar and Edinburgh community arts circles. One of the original archive group members, Billy McKirdy, was in Craigmillar Now when Jimmy popped in to see the space. McKirdy knew Sandra well, and even had a photo of her on his phone, which he showed Jimmy. Others in the archive group also knew Sandra, and later described archiving her work as a way of giving back and thanking her for the help and support she gave them. Some of them even appear in Sandra’s photographs.

When Jimmy mentioned he had all Sandra’s work stored in his shed, the idea of retrieving it was a no-brainer.

“It’s a treasure trove,” says Cloughton of George’s collection. “I still can’t believe that we get to work with it every week.”

Cloughton set up Craigmillar Now after learning about Helen Crummy and the other Craigmillar women while working for Edinburgh based health and well being charity, The Thistle Trust. The day I visit the centre, Cloughton had just stumbled on a set of images George had taken of dancer and choreographer Michael Clark in 1988, presumably when the enfant terrible of the contemporary dance scene was in Edinburgh for the International Festival performances of his ballet, I Am Curious, Orange.

“These are things that are so important,” Cloughton says of George’s images. “They’re important to Craigmillar, but they’re also nationally, even internationally important. It also feels part of what we’re trying to do to raise the profile of artists who haven’t had the recognition they deserve, and communities whose stories need to be told.”

Roots

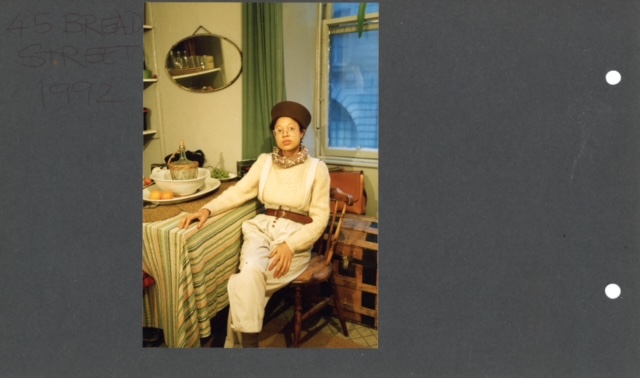

Sandra Angela George was born in Nottingham in 1957, and spent her first seven years in Jamaica with her mother before moving back to the UK. She lived with her mother’s family in the Handsworth area of Birmingham, before moving to Edinburgh to live with her dad. It was while on the other side of the camera that she first became interested in photography.

“She left school at sixteen and went straight into working in admin,” Jimmy tells me, “but she used to model for an Edinburgh hairdresser.”

George’s striking looks and dreadlocks were a gift to stylists and photographers, and she could have easily continued in that world. Sandra had other ideas.

“She was obviously having her photograph taken on a regular basis,” says Jimmy, “and thought to herself, I could do that, so she started to take her own photographs.”

In 1979, George enrolled in the three-year photography course at what was then Napier Technical College, now Edinburgh Napier University. As Jimmy puts it, “It all went on from there.”

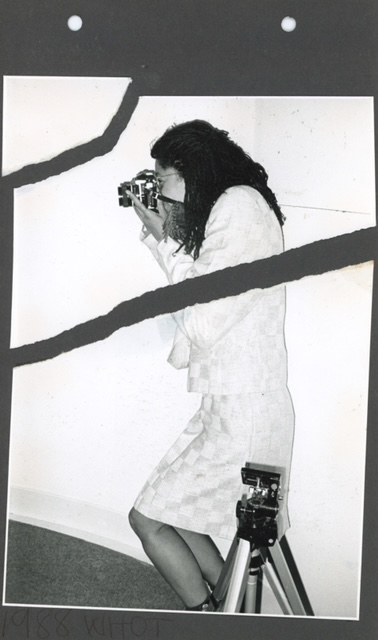

Jimmy met Sandra in 1980, when she was in first year at Napier. He was supervising a group of ex offenders painting and decorating a hostel for homeless women in the Grassmarket. She was taking a series of photographs of the women as part of her course. This set the tone for a socially engaged practice that saw Sandra combine working as a freelance photographer with community education and development projects in Wester Hailes, Craigmillar and other areas on the frontline of social deprivation. George took pictures throughout, documenting the life that went on around the concrete playgrounds she worked among.

“She also worked for national newspapers,” Jimmy remembers, “and she joined the NUJ, but she loved teaching photography, and she taught photography to children and elderly people, as well as working for community newspapers.”

In a pre Internet 1980s, these were vital forums for grassroots activism, and George’s work appeared in the Wester Hailes Sentinel, the Tollcross Times, the Gorgie/Dalry Gazette, and the Craigmillar Chronicle and Craigmillar Festival Times. They were the perfect outlets for George’s work.

The Great Learning

While the education of others in the community was George’s passion, lifelong learning was paramount as well to her own life. Between 2001 and 2004, George studied Fine Art (Drawing and Painting) at Edinburgh College of Art. She followed this with a year-long Community Education course at the University of Edinburgh’s Moray House School of Education.

“She always seemed to have a passion for learning,” Tyler says. “When she was sixteen she wanted to keep studying, and moved out of home and did it herself, because that’s how she was. I love her passion when it comes to education.” If she wasn’t going to get support from home, she was going to just do it anyway. I love her passion when it comes to education.”

With George’s photography and education work entwined, it was a passion that drove everything she did. Suggest this to Jimmy and Tyler, and they both laugh. They’re not being disparaging, but clearly have first hand experience of where her priorities lay.

As Jimmy puts it, “She committed herself to things. Like Tyler was saying earlier about projects she got involved with, she gave them a hundred per cent.”

He illustrates Sandra’s sense of commitment with a bittersweet anecdote.

“A few months before she died, there was a project she was working on, and she was trying to get funding for it, but it didn’t come off. She told me she cried more about that project not going ahead than she did about her cancer.”

Tyler also saw Sandra’s commitment to everything she did first hand.

“As a kid, seeing how much work she was putting into things, I’d have little arguments with her. Money was always a bit tight, and I’d be like, but you’ve just been asked to do all these photos for this organisation, when are they going to pay you? She was like, they can’t pay me just now, because they need to find the money. At that time I wasn’t really aware of how these charitable projects got paid, and I’d say, you really need to start billing them for late payment, but she was just like, I can’t do that.”

Jimmy too bore witness to Sandra’s integrity.

“I remember one time we were skint, and we bumped into a photographer she’d been at college with,” he recalls. “They were really encouraging, saying to Sandra they could get her some work as a wedding photographer, and she was horrified. I was like, but you’re going to get paid all this money for three days work, but she just totally refused.”

Sandra’s more idealistic way of thinking went beyond the practicalities of earning a living.

“She was a devout believer in the ideology of community education,” Tyler affirms. “Absolutely. She wasn’t a religious person, but that was what powered her to do a lot of projects. Then you’ve got the emotional reward of spending time with the kids and giving them a new outlook. Not just kids either, but working with disabled adults as well, doing photography groups with them, and giving them opportunities they’re not going to find on their doorstep, and which can give them a different outlook on life as well.”

As Jimmy observes, “Sandra set really high standards for herself, and she also expected other people to do the best they could. She recognised everybody has different abilities, but she would expect someone to work to the best of that ability, and she would encourage people to achieve the best they could. Some people knew that maybe meant they only were able to do a small thing, and other people were able to do more, but she would push people, and support them.”

Sandra applied the same attitude to people in power.

“She expected the best of professionals,” says Jimmy. “She really expected councillors, or people who were employed by the council, and community education workers to be up to scratch.”

As Tyler diplomatically puts it, “If someone was employed to do a certain job, she would certainly try and encourage them to actually do the bare minimum of that job. So politicians and the like were held to account.”

An accidental trickle down effect of George’s love of learning has been the archiving process at Craigmillar Now itself. After deciding the show should be about Craigmillar, the archive group went through the folders, rooting out as many shots of the area as they could find. After scanning them, they broke into smaller groups, going through hundreds of photos, and talking about what they liked about them. A shortlist was drawn up, with the images on the list printed out and laid out on the Craigmillar Now stage. The group then put them in different combinations, until, after several weeks of discussion, the final twenty images that make up the exhibition were chosen.

“It was interesting to see the reasons why people put certain things together,” Cloughton observes, “and that created a really fascinating series of stories that we started writing down and recording. Some people organised photographs by themes, others were doing it more formally, if the shapes in the pictures were quite similar or if they were from a certain time.

In this way, every part of the process became part of the exhibition.

“This isn’t only an exhibition of Sandra’s work,” says Cloughton. “It’s also the work of over twenty volunteers who have carefully catalogued, re-housed, scanned, edited and selected Sandra’s photographs for more than a year.’

In terms of collective action, this was everything that Sandra was about.

Beyond The White House

Beyond the White House exhibition and thousands of negatives at Craigmillar Now, another part of Sandra George’s archive has yet to be accessed. This stems from her move into using digital cameras.

“The early 2000s is when the folders of negatives end,” Tyler says. “I’m trying to see if I can find the digital stuff from later on, because there’s photographs of when the Scottish parliament was set up, and various projects that she was doing in the 2000s. There are political and social events, various politicians, and I think there are some pictures of royal visits as well.”

Despite her illness, George remained tireless in her approach. Latterly she worked as Youth Services Manager with Hunter’s Hall Housing Co-operative.

“At the end of her life, she was still working for this community youth group,” says Tyler. “It was a charity she’d set up, and the staff were completely oblivious to the fact that she wasn’t going to be around for much longer, because she just kept going. She just didn’t stop. We knew what was on the cards, but the staff hadn’t realised. So for them it was a bit of a surprise, because even when she was very sick, she just wouldn’t stop. Her goal was to try and keep the charity going.”

The photography too continued.

“She still took photographs, says Jimmy. “She always had a camera on her, and would never go out without one.”

“Even being sick,” says Tyler, “there was a development of her curiosity, because she would take pictures of herself as she was going through changes. She would take pictures of her nails when she was undergoing chemo, using photography as a way of coping, and as a sort of a diary as she went through her illness.”

There are drawings too by George, some as part of a story created for Tyler’s son, others of herself.

“There’s a small book that she did a series of drawings in,” says Jimmy. “They’re drawings of her going through all the stages, recording what was happening to her.”

So far, the Sandra George exhibition has attracted more than one of the now grown up occupants of her photographs to turn up at The White House to point out their younger selves.

“We’ve heard some of the older people say, well, that’s such and such, and I remember that building being there,” Jimmy says. “So apart from anything else, the exhibition is an opportunity for people in the area to relive some memories of what is now a few decades ago, and see how much things have changed in recent years. I think there’s a sense in Sandra’s work of being able to look back on how things were, how things are now, and seeing where things have improved.”

Craigmillar Now are getting in touch with people who comment on the photographs via Facebook, and logging the interactions, so they too form part of the archives’ development. Each photograph on the website also has a ‘comments’ section where people can forward any further information about the images.

The exhibition has also prompted an idea for a possible event that could end up as much of a reunion as a celebration of Sandra. Bringing people together in such a way was everything Sandra was about, and both Jimmy and Tyler recognise her achievements go way beyond her photography.

“We’ve heard from many people she worked alongside,” says Tyler. “Not just other staff, but kids and people who were part of various groups, and they say they got into art or music or dance because of the projects she ran. Often that’s become something they’ve kept being into or have developed their career from, or it’s something that they still look back fondly on.

“For me, having some way of keeping all that going would be the goal, to have her name help keep that sense of community education and giving people opportunities alive, I think that would be a major legacy.”

For Jimmy, Sandra’s legacy is more personal.

“This is Sandra’s greatest achievement,” he says, gesturing towards Tyler.

When asked what their favourite images are in the White House show, both Jimmy and Tyler’s choices are telling, not just in terms of the photographs themselves, but about what Sandra gave to them, and what she made happen. For Tyler, it’s the one with the boy holding the pigeon.

“I was there that day,” he says, “so have some vague memories of it. It’s very telling for me, because it was obviously an activity she took kids along to, and it’s giving kids options to try something they definitely aren’t going to get to do on their own. That is very telling for me in the sense of it being about what she believed in, giving kids opportunities to try new things, and perhaps challenge ideas of what they might be expected to achieve in life based purely on what their parents do.”

Tyler can be heard talking about the photograph at https://sandrageorge19881994.squarespace.com/photos/outreach-project

For Jimmy, “I really like the one with the line of children in the playground with a policewoman, and there are all these wee faces. Today, everybody’s taking photographs on their phone, but back then, to have somebody come along with a camera, especially somebody who looked like Sandra, turn up in a playground to take photographs, kids loved her. She was like a magnet.”Sandra George’s Craigmillar Now exhibition at The White House hopefully heralds the beginning of her work belatedly receiving the attention it deserves. There is enough material in her archive to fill Scotland’s national galleries several times over. A published collection of her photographs is similarly long overdue. Whether such institutional attention is something George would have welcomed during her lifetime, however, is a different matter. Either way, it is vital that her photographs are seen as widely as possible rather than being airbrushed out of history.

“We’re so lucky to be working with Sandra’s photographs,” says Cloughton. “Doing the exhibition and seeing the response to it has really galvanised us to think about what we can do next. This is one show of twenty photos by Sandra out of thousands that she took. The potential is really exciting.”

Jimmy and Tyler agree.

“We still need to go through everything and document all the projects she was involved in,” says Tyler. “There is so much more to be seen.”

Sandra George: Craigmillar 1988-1994 runs at The White House, 70 Niddrie Mains Road, Craigmillar, Edinburgh until September 12th. An online version of the exhibition can be seen at www.craigmillarnow.com.

All images courtesy of Craigmillar Now © Sandra George Estate.

Recordings of Craigmillar Now archivists talking about the exhibition can be heard by clicking on each image at www.craigmillarnow.com. Details of archivists involved can be found at https://sandrageorge19881994.squarespace.com/archivists

Craigmillar Now’s archive group meets every Monday between 10am and 5pm. New volunteers welcome.

Help to support independent Scottish journalism by subscribing or donating today.

I wonder why she might have had misgivings around exhibiting?

Neil doesn’t seem to mention any reasons why……..

“Welcome to a family friendly community in South East Edinburgh

Just a short commute from Edinburgh’s beautiful city centre, Bankfield Brae is located in the vibrant suburb of Greendykes creating a new community of 169 high-quality homes.

At Bankfield Brae we have a range of 2, 3 & 4 bedroom homes, as well as 1 & 2 bedroom apartments with flexible living space that’s perfect for modern lifestyles. The development has been designed to form part of the Craigmillar masterplan that will offer new homes, a town centre, public realm improvements and includes plans for a small shop.

You’ll find local garden allotments just a few minutes’ away and a choice of activity groups nearby where you can make friends for life. Within just a short walk there is a range of shops for when you want to stay local, or Fort Kinnaird Shopping Centre is close by providing a wider range of shops and amenities.

Our Sales Information Centres are currently open for pre-booked appointments only. We are also available for you to speak to remotely over the phone or via video appointment. Learn more about our Covid safety measures”

I had a look at the exhibition the other day.

The new housing mentioned in the previous comment doesn’t really have any relevance; under the current system, almost all housing development is private rather than public. It’s out to a level with the new hospitals. I agree that more council housing is needed, if that was the point, though.