Closer? Building a Scottish democracy that works

In the latest paper (re) making the case for independence, ‘Renewing Democracy through Independence’, the First Minister argues that there is a democratic deficit in which: “Westminster retains ultimate power – even on devolved matters – and over recent years, as this paper shows, the UK Government has acted to override decisions of the Scottish Parliament and claw back powers in devolved areas.”

It is not just that Britain is preventing a poll on independence, it is preventing the agreed functioning of devolution. The British State’s centralising powers and tendencies are not to do with individual players and actors they are to do with the nature of the state. As Nicola Sturgeon outlines:

“It has done so despite having the support of a relatively small proportion of the electorate in Scotland. The current governing party at Westminster, for example, has just six MPs representing Scotland and has not won an election in Scotland for almost 70 years.”

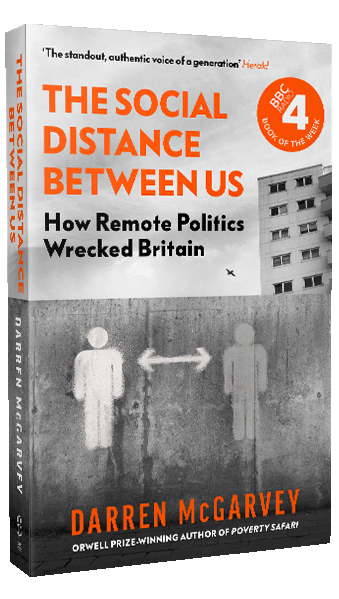

But if this problem and the language around it sound dry and constitutional it is not. As Darren McGarvey puts it in the Social Distance Between Us: “A ravine cuts though Britain, partitioning the powerful from the powerless, the vocal from the voiceless, the fortunate from those too often forgotten. This distance dictates how we identify and relate to society’s biggest issues – from homelessness and poverty to policing and overrun prisons – ultimately depending on how – and whether, we strive to resolve them.”

This ‘social distance between us’ is a mirror of the ‘national distance between us’ – ‘London Rule’ and is part of a wider democratic crisis in society in which the people with power are the monied and propertied class and the corporate elites. This is true everywhere, but in Britain it’s amplified and magnified by remnant feudalism and rampant offshore capitalism.

As the paper ‘Renewing Democracy through Independence’, puts it:

“The House of Lords, the upper house of the UK Parliament, is not elected by the people for whom it passes laws. As of May 2022, there are 764 members of the House of Lords. 650 are life peers, 89 are hereditary peers and 26 are Bishops of the Church of England.39 Just under 29

per cent of its members are women.40 The House of Lords is one of the largest legislative bodies in the world and an outlier in terms of size, hereditary element and unelected composition.41 And as has been observed, “there are still no enforceable constraints on how many peers a Prime Minister can appoint to the second chamber of the UK legislature”.

There are more unelected people making laws in Westminster than elected ones

In 2013-15 we explored some alternative options to this state of affairs in a series of print magazines called ‘Closer’. How could independence be an opportunity to bring democracy closer to people – but also an opportunity to be a first step towards further deeper democracy. It followed on from the work of Finnish futures scholar Vuokko Jarva about a form of ‘Closer’ democracy that is more peer-to-peer more hands on and involved.

I was trying and we’ll continue to try and ask: ‘What changes will help transform Scottish society when we get the powers to control our own affairs? How can we get closer to democracy, closer to land, closer to nature, closer to a way of living that isn’t so distorted by the economics of exploitation?’

In that era, in that moment, we asked with various writers, how to overcome the gender gap that excludes women on multiple levels from society; how the arts and film and broadcast industries which currently exclude people could change to become a huge opportunity for telling ourselves a different story, one of innovation and cultural expectation? How can we use independence as a way to bring a whole generation of young people – who have been betrayed on multiple levels – into democracy and empowerment? How can we repair a local democracy that has been ‘gradually been dismantled over the last 50 years’ from over 400 elected local governments in 1946 to 32 today?

If we take McGarvey’s challenge seriously though, this doesn’t just mean that those closest to, and afflicted by a social problem should be at the heart of consultation and decision-making about solving it. That should be expanded and deepened as a political challenge, acknowledging the forces that would mitigate against it and that those who have suffered the hardest often have no sense of agency left. It is a more difficult challenge to ’empower’ people who have been disenfranchised, and indeed some challenge whether you can ’empwoer’ another person or community at all.

So when we talk about political participation we need also to talk about social inclusion, social justice and basic economic equality before anything else. We need to be able to talk about solidarity and rebuilding a society broken and disfigured by poverty. That’s the real prize of an independent country, a society we want to be part of and that we assume everyone and anyone has a role in: all of us first. That’s a prize worth winning and it’s one within our grasp.

There are examples around the world of institutions and structures that maximise inclusion and participation, instead of exclusion and distance.

From Port Allegre to PARECON (participatory economics), from Mondragon to Erik Olin Wright’s ’empowered participatory governance’ (EPG), from Swiss Cantons to citizen’s initiatives, the practice and theory of a better functioning democracy is clear. The opportunity of moving from being loyal British subjects, to active citizens of Scotland is ahead of us, but we need to do much more than change the flags.

Kali Akuno

The are examples everywhere. One of the most recent, most radical and most inspiring is in Jackson, Mississippi. Here Kali Akuno describes the grassroots mobilisation that launched the young black attorney Chokwe Antar Lumumba to be elected mayor of Jackson, Mississippi, with 93 per cent of the vote in 2017:

“The Jackson Plan is an initiative to apply many of the best practices in the promotion of participatory democracy, solidarity economics and sustainable development, and combine them with progressive community organising and electoral politics.

The plan has three fundamental components designed to build a mass base with political clarity, organisational capacity and material self-sufficiency.”

These are:

- People’s assemblies

- A comprehensive electoral strategy: mounting an effective defence and offence

- Building a local solidarity economy

These are inspiring examples, but rather than being utopian, marginal or operating in wealthy and privileged communities, the Jackson rising operates in the some of the most poorest and marginalised communities, and is succeeding.

Of course the real issue about exclusion in all this is basic but overwhelming economic inequality. The daily everyday experience of unemployment, low wages, zero hours contracts and precarity have now been amplified by a massive attack on the poorest and most vulnerable people by the Conservative’s hugely aggressive welfare reform programme.

This week on Question Time Labour’s Chris Bryant explained how out of touch and socially distanced politicians are. He said: “The thing that shamed me more than anything else was reading that we now have NHS hospitals that are running foodbanks for their staff. Because their staff aren’t able to make ends meet on the salaries they receive.”

Few of us will be shocked to hear this.

And yet we have the lineup of Conservative ‘hopefuls’ threatening tax-cuts and the front-runner Rishi Sunak saying he would ‘Run the country like Margaret Thatcher’. As the Daily Record had it: ‘Tories plan tax cuts as kids go hungry’.

You may say that these radical democratic experiments are a million miles away from the safe and centrist path being laid out before us, and you’d be absolutely right. But the scale of socio-ecological crisis we are in the middle of requires us to think about alternatives that are not the usual bland and failed ones. If we are to have any hope of bridging the ‘ravine that partitions the powerful from the powerless, the vocal from the voiceless’ we must be far more imaginative and braver than before.

It is high time that politicians, pundits, media folk, commentators – people who talk about change for the better – move beyond talking, to turn the talk into actions, start being the change that they (we) want to see.

Thank you, Mike, for this inspiring article. I hadn’t heard about what’s happening in Jackson, Mississippi.

Amazing! Your words make me wonder about the practical steps towards developing a network of people’s assemblies across Scotland, starting, of course, in our local areas.

Do we have a sense of optimal size for gatherings? Could Zoom assemblies be helpful at times, especially to include those whose health conditions or life conditions require them to be cautious of Covid.

This call is not just for a political change, but a deep cultural shift. Helping each other move from a passive consumers of life to engaged participants in thriving communy democracies is a process that calls for a lot of compassion, patience, forgiveness and deep attentiveness to our shared humanity.

Practically, direct democracy and community empowerment can be grown through the formation of grassroots action groups that address a shared interest.

I used to work in an area of Edinburgh which had a much higher than average incidence of suicide among young male residents compared to other communities in the city. Some of those who’d been directly affected by the latest suicide (parents, friends, neighbours, survivors, etc.) were moved by their loss to ‘do something’ for those who had taken their own lives. They got together in a local community space (a function room above the pub) to discuss the problem and explore ways it might be addressed. This action group deliberately excluded the involvement of the statutory agencies – education, health, housing, police, social work – until it had decided on an action plan, and then invited them along to see what (if anything) they could contribute to the implementation that plan. Their collective experience had been that those agencies tended to hi-jack such initiatives for their own corporate ends.

The changes this community of interest effected through its direct action included:

– it’s employment of an independent counsellor who was ‘in’ but not ‘of’ the local secondary school;

– the delivery of mental health awareness and normalisation sessions to every learner in the school, once when they moved up from primary and again when they were about to leave or move up to senior school; and

– the roll-out of Mental Health First Aid training to local residents via their sports and social clubs, pubs and places of worship.

The costs of this were met from the Scottish government’s Choose Life initiative, before the local Health Board diverted the funding of that initiative into staff training.

The action group also mobilised the local community onto creating a space for quiet reflection, expression, and remembrance at the secluded site of many of the suicides took place, as well as several sensory herb beds around the scheme, using left-over materials that would otherwise have been thrown away by the City’s parks department.

These weren’t exception people; they were the very epitome of the educationally and socially ‘deprived’ whom we all too often victimise and keep down as ‘powerless’. The work they did was valuable in itself. But of even greater value was the liberating experience of coming together and doing that work, of being in control of the decision-making process, and of making a tangible difference to their own community. This kind self-guided community development work is crucial to accumulating the resilience and social capital required to empower people; it engenders good democratic habits.

Thank you for this inspiring example, Mr-E Man. Really great to hear about.

Hi Vishwam – really good question on scale. In Athenian democracy the unit was up to 1000 citizens, which interestingly some psychologists believe this is the upper end of how many people you can ‘know’. This is roughly the scale argued for within Libertarian Municipalism of Social Ecology based on ‘neighbourhood assemblies’ But we can maybe think of units operating at different scales – neighbourhood; municipality; regional; national.

See also: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/political-science-research-and-methods/article/abs/direct-democracy-and-government-size-evidence-from-spain/E3D106AD332D40789DECC98090EFBA90

@Vishwam, under Muammar Gaddafi’s Third Universal Theory model, the basic unit of democratic participation was the size of a town or borough. “Democracy is the supervision of the people by the people” says his Green Book.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_People%27s_Congress_(administrative_division)

There were also to be profession-based popular conferences, and these all fed into non-basic popular conferences which selected the People’s Committees to run government administration. The book (I think I have the official English translation) p37 “warns also of the dangers of a period of chaos and demagoguery, and the threat of a return to the authority of the individual, the sect and the party, instead of the authority of the people.”

But isn’t remarkable how the current regime in Scotland mirrors that of the UK as a whole?

The Scottish government’s centralising powers and tendencies aren’t to do with individual players and actors either; they’re to do with the nature of the future Scottish state.

To subvert what Darren says in his book: “A ravine cuts though Scotland, partitioning the powerful from the powerless, the vocal from the voiceless, the fortunate from those too often forgotten. This distance dictates how we identify and relate to society’s biggest issues – from homelessness and poverty to policing and overrun prisons – ultimately depending on how – and whether – we strive to resolve them.

This ‘social distance between us’ is a mirror not just of the British establishment but of the Scottish establishment too, and there’s no evidence that simply making Scottish government independent of UK government in its decision-making will dismantle the inequalities of power of which Darren writes.

The prospectus that Nicola is characteristically handing down to us doesn’t offer any more than empty populist platitudes. What it doesn’t tell us is what the Scottish government will *actually* do on Day 1 of independence, the day after a ‘Yes’ vote, to ‘bring democracy closer to the people’, to make democracy ‘deeper’, to ‘overcome the gender gap that excludes women on multiple levels from society, to include those closest to and most directly affected by social problems in the decision-making about solving it and to remove the structural obstacles we currently put in the way of that self-empowerment? We don’t know; Nicola won’t tell us.

What will the Scottish government actually do on Day 1 of independence to begin the democratic process of dismantling the power inequalities that distort our current public decision-making? Will it, for example, announce the formation of a National Assembly, comprised of (say) 1500 people, 1200 chosen at random from the electoral registry and (say) 300 chosen as representatives of civic organisations, to establish the core values on which our governance should proceed, followed by a Constitutional Assembly of (say) 950 randomly selected citizens to actually draft a constitution the adoption of which will be put before the whole electorate in a direct vote.

Or will it just announce a ‘consultation’ to keep us happy while the government bureaucracy continues with the the actual business of public decision-making and nation-building?

We need to start asking these question of the Scottish government in advance of Day 1. The mere recognition of a principle (that Scotland should be an independent country) isn’t good enough. I’ll not be voting ‘Yes’ to that.

Interesting stuff there with a characteristically perverse and self regarding sign off.

Yes. What is always missing in number man’s objection to voting for independence without ‘more info’ is why he would not vote Yes anyway. The logic would be he prefers things as they are, to the unknown. The unknown may not be much better but would it be worse? There seems no evidence for that, so maybe he just prefers the union. There is nothing ‘wrong’ with this in principle, plenty of people do for all sorts of reasons even if it is just ‘better the devil you know’. But he never articulates his thoughts on this despite the reams of words, and by default anyone who votes No, or abstains, is supporting the continuation of the union. So the question remains, why, and the answer ‘I haven’t got enough info’ is sidestepping the underlying reasons that remain hidden.

I doubt that you’d be voting Yes, anyway.

I too doubt I’d vote Yes/No to a vague question of principle (‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’ – whatever *that* means). I can really only see myself voting For/Against some substantial proposal for how public decision-making will work in an ‘independent’ Scotland from Day 1.

I’m not convinced that voting Yes/No to a vague question of principle will make public decision-making in Scotland any more democratic than it is at present. We should be holding out for more democracy and not be selling our votes cheaply.

Independence solves one key problem.

After that, it’s up to the people of Scotland to decide how we deal with all the other problems.

Those who don’t want that power and responsibility must continue to accept the so-called union, and all the lack of democracy that goes with that.

‘After that [independence] it’s up to the people of Scotland to decide how we deal with all the other problems.’

It would be nice to think so, Sandy, but there’s no indication that, when it comes to public decision-making ‘after independence’, the people of Scotland will get much more of a look in than they do at present. Apparently, we’ll be governed from Holyrood, as we are just now, the only difference being that Holyrood will take on the responsibilities currently undertaken by Westminster.

I sense that Holyrood will not get away with being anything like Westminster.

The geographical and psychological (and ideological) distance of Westminster from Scotland has facilitated the application of systems and policies that most of the people in Scotland don’t want.

I anticipate a big interest in politics and policies among the people here in independent Scotland. I also anticipate a much greater demand for ‘local democracy’ and local participation.

I agree with you, Sandy, that it’s preferable for decisions to be made as locally as possible, by the people most directly affected by the outcomes of those decisions. The British Union, in formal contrast to the European Union, suffers from a distinct lack of subsidiarity/too much centralisation. Increasing subsidiarity within Scotland too would also help us deepen our democracy by making our government less remote.

None of this is the business of Sturgeon or the SNP.

The questions you pose are matters for the first post-independence Scottish Government which may or may not include members of the SNP.

I know. The question is: how democratic will the first ‘post-independence’ Scottish government be? Through what institutional structures and processes will the decisions that will define our ‘independent governance’ from Day 1 be made? The Scottish government’s silence on the matter suggests that our ‘independent governance’ will be business as usual and that we’ll be democratically no better off.

“But isn’t remarkable how the current regime in Scotland mirrors that of the UK as a whole?”

No. We have been under the UK for over 300 years, so of course it resembles it closely. The word “duhh” comes to mind. The point of independence is to give the people of Scotland the ability to mould their own democratic future. It is not to enshrine your own personal, muddled sense of “direct democracy” (which falls apart after even a cursory glance) in aspic. The point about democracy is that people should have a choice. Not have “your choice” foisted on them as a “take it or leave it” fait a complis. That would alienate vast swathes of potential Indy voters. But of course, you know this. If is not your task to inform this debate; it is your task to confuse and muddle the issue. Hence your frankly idiotic stance that sees you criticise UK democracy but threatening to vote to stay with it if Scotland doesn’t go with your own nutty, disingenuous “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

‘The point of independence is to give the people of Scotland the ability to mould their own democratic future.’

But will it? Or will it just give some of the people of Scotland – the existing establishment, the dominant elite that currently controls our polity through the structures and processes of our public decision-making – more power to mould our futures?

We’ve an opportunity here to hold the Scottish government to ransom. We’ll support its ambition to become independent of the UK government in its decision-making in return for guarantees that the structures and processes through which that decision-making is conducted will be more democratic than they currently are. Once it’s gained its independence, that opportunity will be gone.

Who is this “We” you speak of? You talk as if YOU represent “the people” against the government they elected. You talk as if YOU are the arbiter of what the people need, even if they don’t know it yet. Hence the need for a “dictatorship of the proletariat” to make sure they don’t “get it wrong”. There is no indication in your claims that it occurs to you others may have different ideas on Scotland’s democratic future. Others who number in the hundreds of thousands if not millions.

You would have us tether Scottish independence to your own myopic vision of a dystopian “direct democracy” where the “little people” get to decide what colour of park railings they would like, but the big decisions are made by a small elite derived from those and such as those who dominate the tiny political units you champion. Most of whom would come from the land owning, business and professional classes. It’s not a return to a sepia coloured past that I want. I doubt I’m alone in that. At least, back in those days, we still got to vote for our MPs. We wouldn’t even have that if you got your way …. and the people of Scotland, somehow, voted for it.

We are to decide on whether Scotland is to become an independent country or remain part of an asymmetric union. That’s all. Initially we will be a governed from Holyrood, as we are just now, with Holyrood taking on the responsibilities formerly undertaken by Westminster. We will be a standard West European Liberal Democracy. What happens after that is down to the people of Scotland as indicated by them through the ballot box. It is no less a “direct democracy” than the social experiment you want to sabotage the referendum question with.

It’s the very same ‘we’ to whom you referred in your post, the people of Scotland to whom you reckon independence will give the ability to mould their own democratic future.

But will it? Or will it just give some of the people of Scotland – the existing establishment, the dominant elite that currently controls our polity through the structures and processes of our public decision-making – more power to mould our futures?

We’ve an opportunity here to hold the Scottish government to ransom. We’ll support its ambition to become independent of the UK government in its decision-making in return for guarantees that the structures and processes through which that decision-making is conducted will be more democratic than they currently are. Once it’s gained its independence, that opportunity will be gone.

‘…we will be… governed from Holyrood, as we are just now, with Holyrood taking on the responsibilities formerly undertaken by Westminster.’

Then why isn’t this substantial proposal the referenda on which we’ll be invited to vote in next year’s referendum? Why are we only being allowed to vote on an empty matter of principle?

“Then why isn’t this substantial proposal the referenda on which we’ll be invited to vote in next year’s referendum?”

It is. It was all in the Scottish govt’s white paper, Scotland’s Future, in 2014. It was well understood amongst the general population then and remains so now. It does not have to be repeated on the ballot form. People are clever that way.

But it isn’t. That’s just a matter of fact. The proposed referenda isn’t ‘that we will be governed from Holyrood, as we are just now, with Holyrood taking on the responsibilities formerly undertaken by Westminster’ (a proposaI for which I couldn’t in all good conscience vote because, for me, it doesn’t go far enough democratically); the proposed referenda is rather the mere question of principle as to whether Scotland should be an independent country (whatever that might be).

There’s no arguing with the wilfully ignorant.

Have you and “18” ever been seen in the same room? As for Day 1, there’s quite a lot of admin to get through. Please be patient.

The key question is: Who will be in control of that admin? I suspect it will be the entrenched Scottish establishment rather than the Scottish people generally, and it will use that control to consolidate the remote politics, ‘the social distance between us’, the inequalities of power, by which it maintains its ascendancy.

Do you think this could be potentially worse than the current devolved situation then? Feels like a crucial question.

Whether it’s better or worse from the point of view of democracy will depend on who’s in control of ‘the admin’. We need to ensure that, as a condition of our support for independence, the people generally are.

As we know, the over 60s are in the age range least likely to vote for independence.

Must understand why that group in particular have a problem with independence.

And if it is aversion to change, must understand why that is.

And if it’s because many of them have a degree of comfort and wealth which they feel is at risk, that needs to be taken account of.

On the other hand, if they are already feeling hard done by existing government and governance, is there enough evidence to convince them that they might be better-off and at least, no worse off.

@Sandy Watson, the latest Simpsons episode offers an analysis, albeit a USAmerican one, of why old people vote the way they do:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poorhouse_Rock

I’m not sure that explains how I vote.

E F Schumacher pointed out that Small is Beautiful many years ago. Even longer ago – well over 100 years in fact – William Morris and Peter Kropotkin pointed to the problems of centralised power.

Centralised power is always oppressive. It mirrors centralised wealth. It creates centralised ideologies and identities and therefore minorities, people who are outside the tent, to be demonised. From throwing Christians to the lions, to burning heretics at the stake; to massacres of Jews and crusades against Muslims, to ‘uncivilised savages’, ‘reds under the bed’ and ‘conspiracy theorists’.

The only future for Scotland ( and elsewhere in fact) is decentralisation, John Major’s ‘subsidiarity’. Localism, networked circular economies working cooperatively and putting the needs of people and planet first.

Far from bring utopian it is the only thing that can give us a future. And human nature is not separate from the rest of nature: it simply does not operate by endless struggles for power and control but by working together.

Humans are capable of working together for private profit and developing whole ideologies and legal and economic structures to serve those ends. Humans are equally capable of co-operating for the benefit of people and planet.

So I propose a decentralised independent Scotland, with powers devolved to the most local level possible. I suggest European sized local government areas. And breaking up land ownership so that all owners must live and pay taxes in Scotland, holdings are limited in size and subject to responsibilities to the sovereign Scottish people who will be everyone’s landlord.

We need independence from Westminster, and from the World Economic Forum (including Prince Charles). We also need the SNP to abandon their own centralising of power or hand over to a radical alternative.

Our democracy is non-existent not just because of Westminster but because our own system is a failure too.

We need to abolish multi-member wards and regions and the ‘list’ MSPs and bring back individual responsibility and equality for all MSPs . No more voting for ‘parties’. We need to hand control over energy, water, telecomms infrastructure to local authorities and give them the funding and powers to run them in the public interest under democratic oversight.

I suggest we set up a second, revising chamber at Holyrood, chosen at random on the Jury Service basis, that genuinely represents a complete cross-section of Scottish society who can burst the politicians’ bubble and bring a bit of experience and reality into politics.

But, apart from the populist platitudes, these matters are entirely absent from the Scottish government’s prospectus on independence. I suspect it doesn’t want to alienate the Scottish establishment by upsetting the current status quo.

Such a prospectus is the business of political parties and their manifestos for government in a post-independence election. The SNP will possibly be among them. That time will be when your argument has some traction.

I know SNP members who are closet Trotskyites and others who might be labelled Tartan Tories. Others again who are neoliberal in economics and neoconservative in foreign policy; yet more who are nakedly nativist in outlook; others who would pass any Guardian test of ‘progressive’ personhood .

It is remarkable that such a coalition had managed to cohere. Such division as we see now centres on the relative trivia of personalities and identity politics. It is difficult to imagine that unity- and the rigid, centralised discipline enforcing it- long surviving the return of ‘ normal politics

@John Wood, yet decentralised power can be equally oppressive and more sectarian, which we see in the USAmerican states whose governors clamoured for devolved anti-abortion powers. The whole modern project of international human rights legislation is intended to prevent local opt-outs. We see the oppressive nature of smaller enclaves in the UK where religions hold sway, including parts of Scotland and Northern Ireland (think of only very recent changes in blasphemy and abortion criminal law). Bigotry, befuddlement, busybodying, bamboozlement, braggartry, bogosity, bribery, belligerence: all banes of democracy; none made better by local autonomy.

Exactly SD.

Increasing centralisation (though not a goal in itself) was in large part a reaction to the failure of multitudinous smaller authorities failure to address the social problems that, though still present, were far worse way back then. You were fine if you lived in an affluent micro-council. You didn’t have many problems to address and those few you did were easily afforded with the minimum of taxation. However, most micro-councils were far from affluent, had far more social problems to address, but far fewer resources to address them. So you got …. pre WW2 Britain; an affluent, well educated, well housed elite who “governed” and a vast poverty ridden underclass with little education and slums for accommodation. Creating larger council areas and directing central funds to the authorities that needed them most was a game changer for most people.

I understand why the SNP felt it necessary to centralise further when they came to power. They may have been the govt in Holyrood, but local councils were almost wholly Labour, Tory or a combination of both. The Scottish Govt had a manifesto to deliver but were stuck with local councils who had no interest in helping them do it. Too often money was given to councils to address problems the Scottish govt wanted fixed, such as hiring teachers, with that money then either not spent or used for some other purpose, with unionist parties then disingenuously claiming the SNP were reneging on promises. In that respect, local authorities brought centralisation on themselves.

Basically, in my opinion, if you want a fair society where every one has access to good education, health, transport, etc, you need both local and central govt to work together at meaningful levels. A return to “Tory” dominated micro-councils with little, if any, central govt input would not be good for those lacking the resources of the most affluent.

‘Increasing centralisation… was in large part a reaction to the failure of multitudinous smaller authorities failure to address the social problems.’

No it wasn’t. ‘Social problems’ didn’t feature very highly in the concerns of authority when Europe was coalescing into centralised states. Increasing centralisation was about domination, extending discipline and control over growing populations after the Industrial Revolution.

No. That had nothing to do with “centralisation”. Until the latter half of the 20th century, European democratic govt’s had little interest in it. Taxation paid for the military and VERY little else. There was nothing of note to “centralise” with local services, such as they were, being pretty rudimentary by modern standards. So long as the “locals” kept things tight, flew the flag on all the right buildings on all the right days and ensured the “right things” were taught in the schools, they were more than happy to leave it up to them. “Them” being pretty much the same “people” as were running the govt (“is he one of us” type of thing).

Centralisation only became a thing after WW2 when socialist parties started setting agendas with the betterment of social conditions for the heroes returning from war a priority. That required money the tiny local authorities did not have, or were unwilling to raise, so central govt was needed to top up the budgets. Larger local authorities are able to provide larger, more affordable services, and are better able to ensure equity amongst the general population. Also, when govt’s start paying for something, they kind of want to ensure the money is going where it is supposed to. Hence “centralisation”.

Well, I’d date it a little earlier, from the time of the Enlightenment, when ‘social issues’ and ‘biopower’ first became a thing and the modern European state and its institutions began to emerge as a mechanism through which populations could be centrally controlled and ‘perfected’ through discipline and punishment.

Historically, the most drastic transformation of power formations took place during the nineteenth century, when the state assumed greater power over the regulation and administration of life through the movement for social reform. Biopower and its centralisation only reached its epitome under totalitarian regimes of the 20th century.

But power in those American states (many of which are larger that Scotland) isn’t decentralised. That’s why they’re susceptible to the sort of tyranny you describe. Centralised power is more susceptible to capture.

Ermmm …. yes it is decentralised. It just doesn’t suit your argument to admit it. This from The White House site;

“Municipal governments—those defined as cities, towns, boroughs (except in Alaska), villages, and townships—are generally organized around a population center and in most cases correspond to the geographical designations used by the United States Census Bureau for reporting of housing and population statistics. Municipalities vary greatly in size, from the millions of residents of New York City and Los Angeles to the few hundred people who live in Jenkins, Minnesota.

Municipalities generally take responsibility for parks and recreation services, police and fire departments, housing services, emergency medical services, municipal courts, transportation services (including public transportation), and public works (streets, sewers, snow removal, signage, and so forth).

Whereas the Federal Government and State governments share power in countless ways, a local government must be granted power by the State. In general, mayors, city councils, and other governing bodies are directly elected by the people”.

It sounds pretty much like what you are arguing for.

What I’m arguing for is a more substantial referenda that at least outlines the structures and processes of decision-making by which our independence will be defined. This might be some form of more decentralised and participatory democracy (which would get my vote) or the centralised representative democracy of the sort that we have now (which wouldn’t). It’s the fact that ‘we’ (the people of Scotland) aren’t getting that choice that I have a problem with.

I don’t see why my saying that ‘we’ (the people of Scotland) should be given this choice is an imposition.

“I don’t see why my saying that ‘we’ (the people of Scotland) should be given this choice is an imposition”.

1. That “choice” is for once independence has been achieved.

2. Why is it only your particular pet system “we” get to vote for? What about the bloke down the roads favourite? What about that woman in Dundee’s favourite? What about the guy in Millport’s choice? What about the literally hundreds, if not thousands, of possibilities out there? How many pages thick is the ballot paper going to be? Or is yours just so super-super brilliant that it’s self evidently the only one that should be on offer?

3. You’re only here to put people off independence and get them talking about your nonsense instead of whatever the real topic is. Albeit successfully …. so well done.

‘That “choice” is for once independence has been achieved.’

No it’s not. For, by then, we’ll be locked into our own wee Westminster system of decision-making and the moment of change will have passed.

And I’m not asking for my ‘pet system’ to comprise the referenda in the forthcoming election. I’m asking the Scottish government to put its cards on the table and give us a vote on its plans for our independent governance and its transition to independence. I’d be more than happy to see that referenda to be ‘That we will be governed from Holyrood, as we are just now, with Holyrood taking on the responsibilities formerly undertaken by Westminster’. At least I could then vote ‘No’ to that rather than spoil my ballot paper like I had to do the last time. How other people voted would, of course, be up to them.

As I said above, there’s no arguing with the wilfully ignorant.

Indeed, you did. But that’s just name-calling and doesn’t signify.

It’s not name calling if it accurately describes what someone is doing. Everything you claim has never existed in the Scottish govt’s plan for an independent Scotland is comprehensively covered in the White Paper “Scotland’s Future”. It was debated in homes, pubs, workplaces, on-line and in the media before Sept 2014. Yet you claim to believe it has never existed. Everything you continue to bang on about has been thoroughly debunked but you pretend it hasn’t been. I can only assume you are either an idiot (doubtful), a plant (possibly) wilfully ignorant (definitely) and/or a sh*t stirrer (again, definitely).

I scoured the prospectus on independence that the Scottish government produced for the 2014 referendum at the time. It contained a lot of things that it would have properly been the business of the the first post-independence government to decide (e.g. remaining within a UK currency union, the removal of Trident, the establishment of a state broadcaster, the nationalisation of the Royal Mail in Scotland, etc.). What it didn’t contain was anything on government structure and process. For example, it dictated that Scotland would have a written constitution after its government became independent, but remained silent on the crucial and fundamental question of how that constitution would be written and by whom. The White Paper was a nice glossy sales brochure, depicting the land of milk and honey that an independent Scottish government would deliver to the Scottish people, but it left me in the dark as to how much and what kind of input the Scottish people would have in the crucial decision-making that would define the new Scotland politically. So far, Nicola’s briefings – even, curiously enough, her most recent one on democracy – have been no more enlightening.

I can only suggest you “scour” again. This is verbatim from the White Paper you claim to have “scoured”;

“One of the first and most fundamental tasks of the Parliament of an independent Scotland will be to establish the process for preparing Scotland’s first written constitution through an open, participative and inclusive constitutional convention. A written constitution should be designed by the people of Scotland for the people of Scotland.

The process by which Scotland adopts a written constitution is as important as it’s content. The process will ensure that it reflects the fundamental constitutional truth – that the people, rather than politicians or state institutions, are the sovereign authority in Scotland.

The pre- independence legislation will place on the Scottish Parliament a duty to convene an independent constitutional convention to debate and draft the written constitution.

A constitutional convention will ensure a participative and inclusive process where the people of Scotland, as well as politicians, civic society organisations, business interests, trade unions, local authorities and others, will have a direct role in shaping the constitution.

In taking this path, Scotland will be following in the footsteps of many other countries, not least the United States of America, whose constitutional convention in 1787 drafted the constitution if the United States.

International best practice and the practical experience of other countries and territories should be considered and taken into account in advance of the determination of the process for the constitutional convention. In the last decade, citizen-led assemblies and constitutional conventions have been convened in British Columbia (2004), the Netherlands (2006), Ontario (2007) and Iceland (2010). Since 2012, Ireland has been holding a constitutional convention to review various constitutional issues.”

There is a whole chapter on this. And yet you claim to have missed all this in your “scouring”. Then again, putting a gloss on it, perhaps your definition of “scour” is different to mine.

Yes, I know; I read that chapter. All very fine and inspiring words. My sticking point was the absence of any indication as to how and by whom the process for the constitutional convention would be determined. As far as I could gather, this would still be determined by the f*ck*ng government rather by a citizens’ assembly, as in most of the exemplars it cites. In Iceland, for example, the core values on which the constitutional convention was to proceed were determined by a preliminary national assembly of 1,500 people, 1,200 of whom were chosen at random from the national registry and the remaining 300 as representatives of companies, civic institutions, and other communities of interest; the government (which had demonstrated big time that it wasn’t to be trusted) was side-lined altogether from the determination of how and by whom the constitution was to be drafted. I could have voted ‘Yes’ to something like that.

That would be covered by;

“International best practice and the practical experience of other countries and territories should be considered and taken into account in advance of the determination of the process for the constitutional convention.”

Feel free to change the narrative again.

And what’s still missing is ‘by whom’ that practice and experience will be considered and taken into account in advance of the determination of the process for the constitutional convention.

That “by whom” is also missing from what passes for your own preference. If that process does not begin with the democratically elected representatives of the people then who does it begin with? A self selecting group of elites to your liking? You, by any chance?

Not at all, Me Bungo. As a said a couple of posts ago, I’d give my ‘Yes’ to an independence proposal that allowed something like a preliminary national assembly of 1,500 people, 1,200 of whom were chosen at random from the Scottish electoral register and the remaining 300 as representatives of companies, civic institutions, and other communities of interest in Scotland, to consider and take into account the practice and experience of other countries in nation-building in advance of its determining the values and processes by which our constitution would be drafted. What makes you think that the values and processes this randomly selected national assembly would come up with would conform to what passes for my own preference?

@Lord Parakeet the Cacophonist, what is your plan or roadmap for getting a national constitutional assembly for the UK to bring the joys of direct democracy to it?

My own personal roadmap is to continue doing whatever I can to subvert the hegemony that capitalism exercises over my cognitive, evaluative, and practical behaviours while working with my neighbours to expand the autonomy of our own real communities and to resist the involvement in our public decision-making of more imagined communities such as Dumgall, Scotland, the UK, etc. other than in a subsidiary role.

BTW See what I found!

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1-NdQXBB9DXtMFr9-00TlA-ohSyHhNknV/view?usp=sharing

Last post on this self suspending nonsense;

“As a said a couple of posts ago, I’d give my ‘Yes’ to an independence proposal that allowed something like a preliminary national assembly of 1,500 people, 1,200 of whom were chosen at random from the Scottish electoral register and the remaining 300 as representatives of companies, civic institutions, and other communities of interest in Scotland …. ”

But of course, the people who would have to propose and sign off on this particular form would be …. the democratically elected representatives of the people …. as described in the Scottish govt’s 2014 White Paper. I believe you are intelligent enough to realise this. I believe you know that what you claim prevents you from voting Yes is a fantasy, and impossible to deliver without the participation of those you would deny any such participation. That is why I believe your presence on this site is malicious and not designed to inform or engage positively with the real issues.

Not at all, Me Bungo. All that would need to happen for such a proposal to become the referenda of the forthcoming referendum on Scotland’s governance is that the government replace its current empty question of principle (‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’) with a firm proposal to (say) convene a preliminary national assembly of 1,500 people, 1,200 of whom will be chosen at random from the Scottish electoral register and the remaining 300 as representatives of companies, civic institutions, and other communities of interest in Scotland, to determine the values and processes by which our constitution will be drafted and our independence defined. As I say, I could vote ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to such a proposal, depending on what it was and whether or not I agreed with it; as could ever other voter in Scotland.

But you’re right to be pessimistic about this ever happening. The political establishment in Scotland has no intention of ever handing the determination of our future governance to a national assembly it can’t control.

“Not at all, Me Bungo. All that would need to happen for such a proposal to become the referenda of the forthcoming referendum on Scotland’s governance is that the government replace its current empty question of principle (‘Should Scotland be an independent country?’) with a firm proposal to (say) convene a preliminary national assembly ….”

I’m assuming everyone else can see the complete lack of logic (lets be kind and call it that) in claiming the democratically elected representatives of the Scottish people deciding to implement “number soup’s” preferred process somehow does not require the democratically elected representatives of the people of Scotland to be involved. Its like saying if you use a kettle to boil water the kettle, somehow, has nothing to do with it. It is demonstrable nonsense FFS.

I’m presuming our elected representatives in the Scottish parliament would have to agree whatever referenda the Scottish government wanted to put to the Scottish electorate in a referendum, whether it’s the question of principle it’s decided to go with, or whether it’s some more substantial proposal for a preliminary national assembly and subsequent constitutional convention along the lines that I’ve suggested, or whether it’s something quite different still. Why wouldn’t it?

@Lord Parakeet the Cacophonist, you don’t offer any reason or empirical evidence for claiming that central power is easier to capture. On the contrary, reason and empirical evidence suggest that smaller administrations are more prone to capture by corporate or religious interests:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Company_town

British politics was for a long time contested by powerful opposing blocs (roughly landowners versus industrialists) neither of whom was able to capture the state (partly because it was already captured by the winning organised crime family, aka royalty).

But that would be an argument against independence (or, indeed, devolution, the smaller concentration of power of a centralised Scottish government being easier to capture than the larger concentration of power in Westminster.

Anyhow, on decentralisation and its rationale, see the United Nations Development Programme’s paper http://web.undp.org/evaluation/evaluations/documents/decentralization_working_report.PDF

Well I seem to have started some sort of discussion anyway, which is (to me at least) a Good Thing.

It would be absurd to vote No to independence because you didn’t like the SNP’s preferred option. Surely independence means we get to choose what sort of Scotland we want. We don’t need to pretend that independence = whatever the SNP says it is. We get the chance to make mistakes and correct them. Some people might even vote Yes top get rid of the SNP – it’s the only way that can happen. I set out my own preference for a decentralised model – its up to those with a different vision to put that forward. Surely, the most important thing is that we have a public debate about this. Otherwise we will eventually discover that Scotland outside the Union is just another US dominated, neoliberal country, like Ireland is rapidly becoming. Of course it may prove hard to imagine anything else, and you might want that anyway, in which case, good luck to you. But for me it would be a wasted opportunity. It’s surely essential that we are offered a variety of different possibilities.

I do think that independence from Westminster needs to be the first step on a path of further decentralisation of both power and wealth (which go together). if there are communuties that have very (to me) reactionary views, let them have them – it is not for me to impose my views on them. But equally, a decentralised system makes it much harder for them to impose their views on me. I do not agree that a network of small, independent minded communities, especially with decentralised, circular economies – is easier to take over and control than one large one. In fact the opposite is true.

Centralisation here in the Highlands means being ruled by people who don’t live here and generally regard this land as a rich operson’s ‘wild playground’ where the natives and the local residents don’t matter. The Gaidhealtachd is a colony’s colony. The British Empire like all Empires was a centralised power structure, which exploited and ransacked the world and ruled by violence rather than consent. Today we have its legacy: One “local’ authority, the Highland Council, based in Inverness and sees the vast area under its jurisdiction as simply a hinterland for a fast growing urban centre. It covers an area the size of Wales, or Belgium, or Virginia. It’s too big, and too urban. And in practical terms it doesn’t work. If I take a job with the council, and my family consents to move with me to the highlands, it’s a trap. If it doesn’t work out I can’t go and work for the local authority down the road because that might be well over 100 miles away. So the Council struggles to attract and retain good staff. It centralises services which is not efficient in delivery and it deprives rural areas of much needed jobs and income. So as cities have always done, it sucks the life out of peripheral areas and into the centre. And Scotland has been divided between Highlanders and Lowlanders for centuries. Just as Scotland needs its voice heard so do the Highlanders who have suffered so much. Lets invite the diaspora back and rebuild a thriving prosperous Highlands and Islands out of the ashes of the Empire. I know there are some Highlanders in the Scottish Government, but I want to see a vision for Scotland that respects differences.

‘Surely independence means we get to choose what sort of Scotland we want…’

But will it, John? That will rather depend on how the decisions that will define post-independence Scotland will be made? I’d like to know this before I commit my vote either way.

‘Surely independence means we get to choose what sort of Scotland we want…’

But will it, John? That will rather depend on how the decisions that will define post-independence Scotland will be made? I’d like to know this before I commit my vote either way.

The decisions that define post-independence Scotland will be made by Scots, through the ballot box. That is the whole point! Whatever the SNP propose. It’s called democracy. Voting No means that all decisions remain at Westminster.

‘The decisions that define post-independence Scotland will be made by Scots, through the ballot box. That is the whole point! Whatever the SNP propose. It’s called democracy. Voting No means that all decisions remain at Westminster.’

Not all decisions, John. Much of the decision-making that pertains only to the people who live in Scotland has been devolved to the Scottish government. Decision-making that pertains not just to the people who live in Scotland but also to the people of Britain more generally remains under the jurisdiction of the UK government.

I’d be happier were our government based on the principle of subsidiarity rather than devolution, with decision-making being delegated ‘upwards’ as a when required rather than conceded ‘downwards’ as a kind of liberty. But that’s not an option in the forthcoming referendum on Scotland’s future, which leaves me with only a Hobson’s choice, which is no real choice at all.

“Much of the decision-making that pertains only to the people who live in Scotland has been devolved to the Scottish government. Decision-making that pertains not just to the people who live in Scotland but also to the people of Britain more generally remains under the jurisdiction of the UK government.”

Power devolved is power retained, and the Scottish Parliament has been overruled again and again by Westminster. Powers have been reserved to Westminster and legislative consent regarding the exit from the EU was refused but ignored. So much for the ‘most powerful devolved parliament in the world’. We are completely hamstrung by this so-called ‘Union’ – we are simply a colony of England (or rather, London). This is why we urgently need independence. We are ruled by the dictat of a corrupt, neo-fascist government that has no democratic mandate in Scotland.

@John Wood, perhaps it is more reasonable to think that (political) power is only power when it is exerted (successfully). This is why is almost always uncertain. Nicolae Ceaușescu thought he had power when he gave his final speech. Until the development of automated nuclear weapons, an executive ruler usually had to worry about their armed forces disobeying their next order.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanian_Revolution#Ceaușescu's_speech

Since political power is such a chimera, I think it is not a reliable concept to use in discussions of building a constitution state, except in terms of constraining it: so, for example, in many constitutions there are limits on terms of office, which when broken generally signify a phase-change in a polity, for example between a republic and imperial rule. International human rights legislation, for example, are typically rights against state power; they don’t necessarily empower individuals, except to access formal justice and so forth. I referred to the concepts of mandamus (must do) and ultra vires (must not do, as exceeding powers) in local government in an earlier comment. The problems that you allude to are the legacy and continuance of British imperial rule, and the extent to which the exertion of power takes place (probably) to a large extent in the shadows (think of all those undeclared meetings of UK ministers and the Queen’s Consent scandals as only the tip of the iceberg).

If we don’t want an Independent Scotland to follow the Westminster/British imperial model, we have to think in terms of how to constrain political power, and whether conventional checks and balances are sufficient or deficient (if the latter, seek other examples or devise new ones), and the balance to be struck between personal autonomy and collective responsibility.

Indeed, John; devolution is not independence. Subsidiarity (the power-relation that at least formally obtains between the union and its constituents in the European Union) isn’t independence either. Under both devolution and subsidiarity, some decision-making power is retained by (in the case of devolution) or delegated to (in the case of subsidiarity) some larger, more extensive court.

‘We are ruled by the dictat of a corrupt, neo-fascist government that has no democratic mandate in Scotland.’

The same flag-waving, virtue-signalling hyperbole was used by UK nationalists in relation to the EU bureaucracy and leadership. If I were so minded, I could use it myself of the Scottish bureaucracy and leadership that has no democratic mandate in Dumgall or in the Northern Isles, etc.

(BTW, how will independence fix that latter democratic deficit?)

Thanks for this thought-provoking piece. A friend sent me this link to a chapter by Kali Akuno that gives a little more detail about the Jackson experience:

https://jacksonrising.pressbooks.com/chapter/the-jackson-kush-plan-the-struggle-for-black-self-determination-and-economic-democracy/

This explains that the Jackson initiative is the latest chapter in a very long history of resistance by the Black community. This got me wondering from where such grassroots initiatives might emerge in Scotland. While the government at Holyrood can play a role in supporting such initiatives, and while effective support for them is more likely to come under independence, it seems to me that their ultimate success relies far more on community mobilisations than on central prescriptions.

Grassroots initiatives come and go in Scotland in response to very specific local crises in situations where government intervention is absent or has failed. There are thousands of such initiatives all over Scotland, and they provide an alternative paradigm for democratic governance.

If you read Kali Akuno’s paper, you’ll see that he is talking about a liberation movement that has been going for very many decades, right back to the time of slavery, and that the ‘Jackson rising’ is but the last in a long line of such emergent initiatives. This goes way beyond the kind of grassroots mobilisations you mention, of which I am well aware. The point is that this one did not ‘come and go’, but seems seems to encompass a deep and lasting shift in culture and attitudes. The importance of this aspect was also underlined by Vishwam in an earlier post.

But that ‘deep cultural shift’ away from dependency to independence doesn’t just happen. It requires the patient work of community development, growing capacity and agency through grassroots initiatives.

The Jackson Plan is a good example of how such community development, which has re-emerged time and again in Black communities in Mississippi in response the failures of government, can be harnessed to affect that cultural shift and deepen democracy.

But Mississippi isn’t Scotland; in terms of community development and shifting away from our culture of dependency, we’ve got a lot of catching up to do. It’ll be a while before we’ve grown the democratic capacity for a Jackson Plan.

Another glaring omission in Nicola’s paper on democracy is an explanation of how independence will correct the democratic deficit of which she speaks in relation to Scotland. The people of Dumgal, the Northern Isles, etc. regularly end up with governments in Holyrood for which they didn’t vote. How will Scottish independence sort that?

Well said Bungo.

I don’t want Scotland to be a shining light to the rest of the world..why should we..

Independence first ..fight it out among ourselves and to hell with everybody else..maybe one day we can set a role model to the rest of the world.( who cares ) ..we just want to run our own country ( like everyone else) without our ghastly neighbours south of a hard border sticking their nasty noses into our affairs…that too much to ask?

NOPE.

Dropping out of this conversation.

Level of discussion pretty poor.

The word ‘power’ appears in various forms some forty times here, in article and comments. I think that political power is something we should recognise as problematic and something to be constrained (by usual and innovative checks and balances). What we should be aiming for, I believe, are good governance and healthy collective decision-making, not arguing about where political power should lie (elites, proletariats, central executive or local assembly). I am not well versed on the range of opinions about political power, but Wikipedia seems as good a starting point as any:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_(social_and_political)

In my view, one of the key concepts for a new Scottish polity is distributed authority. That is, how we take into account legitimate views on Scottish policies and governance, in my view from anyone (and any living thing, through reasonable proxies) affected by them. This will include future generations, people living in other countries around the world, non-human life, global science especially the life sciences and climatology, and appropriate civil groups. For example, anyone should have the right to formally petition the Scottish government on any material grievance, including environmental degradation from Scottish-originated pollution, and injury from war material produced in Scotland, with an impartial judiciary based on the highest international norms.

In other words, I hold somewhat to the idea that political power corrupts, and therefore the solution is not to give power to the powerless, but constrain and eliminate political power whose use tends to abuse at any level, from emperor to household patriarch, say. The great task of democratic constitution-building is to go as far as is reasonable in restricting the power of democracy. Democracy is, after all, a means-justifies-the-end hollow kind of ideology, and a corrupt demos will not only enact corrupt policies, but actively resist the cleaning up of politics.

Power as such isn’t problematic. Inequalities of power are. They’re problematic insofar as (according to Habermas’s theory of communicative action) they distort the ideal speech situation that’s a condition of our communicative competence as a society. In an ideal speech situation, participants are able to evaluate each other’s assertions solely on the basis of reason and evidence, in an atmosphere completely free of any physical or psychological coercion, and are motivated solely by the desire to obtain a rational consensus or ‘general will’ rather than any personal or party interest.

@Lord Parakeet the Cacophonist, you are simply wrong in implying that equalities of power somehow cancel each other out. In the Wild West, widespread possession of a firearm was considered by some to be an equaliser, but it did not bring justice or good public health outcomes. In most countries of the world, the state (or international norms) typically steps in to prevent ordinary people exerting too much power. This is, however, often drafted to preserve the powers of the elite. Apparently there is UK legislation that prevents private subjects from setting off nuclear explosions, that for some reason, oh yes that one, royalty is exempt from. Again, we see that powers are closely related to the concept of licence. What goes on in areas of the world where people can do what they want will tend to negatively impact us all. For example, unregulated biolabs, AI weapons factories, cyber schools and nerve agent research. Similarly, even a small locale could wipe out species who migrate through it or nest in it.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jul/13/faroe-islands-branded-an-abattoir-as-quota-set-for-slaughter-of-500-dolphins

Where on earth did I imply ‘that equalities of power… cancel each other out’? I don’t even know what that means. Please explain!

Power equality in any communicative context (i.e. in any economic, social, or political, exchange) is simply the inability if any individual or party to exert any physical or psychological coercion over the cognitive, evaluative, or practical behaviour of any other in their decision-making.

“For example, anyone should have the right to formally petition the Scottish government on any material grievance, including environmental degradation from Scottish-originated pollution, and injury from war material produced in Scotland, with an impartial judiciary based on the highest international norms”.

It is my understanding that right already exists so long as you get enough signatures.

@Me Bungo Pony, well, the requirement to collect enough signatures should be irrelevant for a petition of grievance. I said petition the government: in my currently preferred model, there would be no party-political parliament to petition. The Scottish Parliament website says:

“You should contact at least 1 of your MSPs or the Scottish Government before submitting a petition.”

https://www.parliament.scot/get-involved/petitions/about-petitions

My view is that this should not be restricted to Scottish citizens, and external monitors are required (perhaps international Ombudspanels or something), and not something that the Scottish government can just unilaterally decide to brush off, as apparently they can now. Obviously there could be vexatious claims. I am saying that filtering these would require a more scientific or evidence-based approach than a partisan political one.