The Return of Radical Independence?

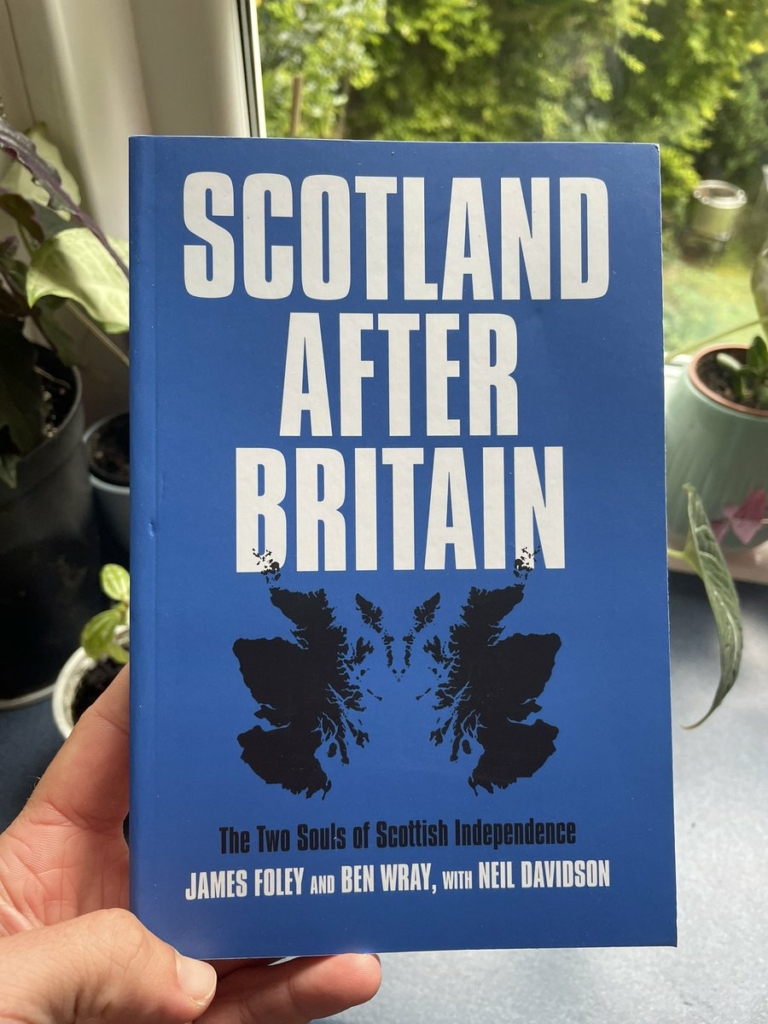

James Foley and Ben Wray, with Neil Davidson, Scotland After Britain: The Two Souls of Scottish Independence, Verso Books, 2022

Ever since its initial electoral breakthrough at the Hamilton by-election of 1967, Scottish nationalism has had a close but complicated relationship with the radical left. While the SNP itself has usually been a centre or centre-left party, intellectuals and activists influenced by the Marxist tradition have been the grit in the oyster of the campaign for Scottish independence. The most famous example is Tom Nairn, whose influential writings in the New Left Review and elsewhere provided acerbic commentary on the national movement’s shortcomings while simultaneously developing a critique of the United Kingdom that indelibly influenced all subsequent versions of the case for Scottish independence. Nairn is one prominent figure in a longer lineage of leftists who have stood both among and apart from the SNP. For such radicals, independence is consonant with their socialism because it offers an opportunity to break up an ancient imperial state and to create a new Scottish polity more favourable to working class interests.

The late Neil Davidson, one of the co-authors of Scotland After Britain, was another leading light of the Marxist left who became engaged with the cause of independence. Davidson and Nairn had their differences, with Davidson affiliated for much of his life with the Socialist Workers’ Party rather than the more inchoate New Left formation that Nairn was associated with. But they shared a commitment to placing workaday Scottish political life in its theoretical and material contexts, one of the abiding (and welcome) intellectual habits fostered by the Marxist tradition.

Scotland After Britain was conceived and begun before Davidson’s untimely passing in 2020. But the bulk of the work on the text passed to his co-authors, James Foley and Ben Wray, who are themselves representative of the new generation of leftists who rose to prominence during the 2014 referendum and have carried forward the tradition of Marxist advocacy for independence.

A radical take on independence?

The time is certainly right for a fresh radical take on the independence debate. The SNP finds itself caught between a mobilised support base and an electorate that is content with the SNP as a governing party but less certain about the desirability of an independence referendum in the immediate future.

As Foley, Wray and Davidson (hereafter FWD) point out, for those who are strongly committed to independence but less invested in the fate of the SNP as a political party, there is a danger that this political dynamic will lead to the victory of what they call ‘neo-autonomism‘ (a term they borrow from Catalonia). They suspect that the SNP’s leadership would in fact be content with governing a devolved Scotland, were there to be no clear constitutional path forward for another independence referendum. In such a scenario, SNP politicians would continue to deploy nationalist rhetoric to maintain the SNP’s status as Scotland’s leading party but, when push comes to shove, would refrain from using that framing to prioritise the goal of independence. How did the independence movement reach this seemingly parlous position?

FWD deftly retell the last decade or so of Scottish history with an eye both to the long-run structural forces that have shaped politics and the role of popular agency and political leadership in channelling these forces behind a nationalist political tide. Their starting point is a firm rejection of the idea that the contemporary independence movement has its roots in a long-run struggle to recapture Scotland’s historic statehood. Independence, they argue, only gained any real political salience around the years 2012-14, since no significant mass movement in support of this objective existed before then.

This chronological point should be distinguished even from the consensus among historians and political scientists that the rise of Scottish nationalism began in the 1960s and 1970s. FWD argue that the current campaign for independence should be seen as distinct from the SNP’s initial electoral successes amid the economic turmoil of the 1970s. In their view, the correct historical context for today’s independence movement is the crisis of neo-liberal globalisation triggered by the financial crisis of 2007-8. Scotland’s local political debates should therefore take their place alongside Trump, Brexit, the Greek crisis, the gilets jaunes, and any of the innumerable other ways in which distributive conflict has been heightened around the globe by recession, austerity, and the waning ideological legitimacy of neo-liberal economics.

The book therefore offers a ‘movementist’ account of the 2014 referendum. In this telling, although elite political calculations among both nationalists and unionists led to the referendum, political leaders on both sides of the divide found that the popular mobilisation that it triggered far exceeded their expectations or capacity to control it. In particular, the authors stress that the social base of the independence movement created by the referendum was younger and more working class than the other side.

Although they are clear-eyed in their assessment of Alex Salmond’s limitations as a politician and a human being, FWD nonetheless see Salmond as the leader who adapted most quickly to this new political terrain and was able to embody the anti-establishment mood in the run-up to the referendum. In contrast, Nicola Sturgeon emerges from this book as more aligned with middle-class professionals, notably those economically-secure liberals pushed into the SNP camp as a result of the Brexit vote.

For FWD, Brexit is where matters started to go awry for the independence movement, since in their view Sturgeon’s leadership has ended up reflecting the preoccupations of these new middle-class supporters of independence. Sturgeon and her associates therefore present independence less as a radical rupture from the neo-liberal status quo and more of an attempt to recapture the stability and technocratic competence associated with EU membership.

It should be said (and the authors are obviously aware of this) that the official SNP position has not in fact changed that much – the independence prospectus put to the electorate in 2014 similarly stressed the economic continuity that a Scottish state would enjoy within the EU and the monetary institutions of the remainder of the United Kingdom. But it is certainly true that Sturgeon’s leadership has been stylistically cautious and pragmatic where the spirit of 2014 (and to some extent the rhetoric of Alex Salmond at the time) cultivated a more insurgent mood among independence supporters.

A serious contribution posing important questions

There is a lot to like about this book. It prosecutes a serious case that ruthlessly strips away the myths that surround Scotland’s politics. It confronts with honesty the unequal distribution of power and wealth in Scottish society and the distance that the nation must travel to live up to its professed left-wing ideals. Taken as a whole, it is one of the few attempts to offer a forensic analysis of contemporary Scottish politics that goes beyond the manoeuvring of political leaders.

But I was left with two questions after reading it. First, is today’s movement for independence best understood as a rebellion against neo-liberal capitalism, and specifically as a product of the years around the financial crisis? There is something to this claim, but I would stretch the chronology further back and say that contemporary Scottish nationalism is a response to deindustrialisation, a long-run trend from the 1960s that fundamentally altered the economic structure of Scottish society and which was pushed forward most dramatically by the Thatcher government.

As a result of its association with Thatcherism, this secular shift from a manufacturing to a service sector economy was understood politically within Scotland as an undemocratic imposition by the UK state. In this sense, the case for devolution articulated by Scottish Labour in the 1980s and 1990s was in fact similar to the case that would be made for independence in the twenty-first century – and those debates of the 1980s and 1990s can be seen in retrospect as having primed a section of the Scottish Labour vote to support independence, if forced to choose between a Conservative government in London or a new Scottish state.

The authors are reluctant to concede this longer-run story about Scottish nationalism because they would prefer a more delimited account of the grassroots mobilisation of 2014. They want to stress that the assertion of national identity was less significant to the independence movement than demands for economic and political democratisation in the wake of the failures of neo-liberalism.

But it’s difficult to give a full account of recent Scottish political history without acknowledging that those demands for democratisation obtained much greater political salience because they had already been artfully woven into a pre-existing Scottish national identity by artists, intellectuals, politicians, and activists from the 1970s onwards. In that sense, elites had more of a role to play in the rise of the Scottish nationalism than FWD, with their focus on grassroots social movements, allow.

Second, how plausible is the political strategy that the authors recommend? The dilemma faced by the independence movement is in fact more intractable than the book suggests. The daunting test of political leadership that confronts Sturgeon and her colleagues is somehow to maintain a movement that can project simultaneously both a more centrist, technocratic profile and a radical, anti-establishment one.

The feasibility of a politics of radical independence

The book argues that, of these ‘two souls of Scottish independence’, the cautious, centrist pole ought to be displaced by the more radical vision. But if any serious pressure is to be applied to the UK government in the next few years, the chief task for supporters of independence is to raise popular support for a new Scottish state (and for a second referendum) well above 50 per cent in opinion polls.

Assembling a super-majority of say 60 per cent in support of independence would surely require a broad, socially heterogenous coalition that cannot be built purely on the working-class mobilisation that FWD prioritise. On the contrary, it would presumably demand an alliance between the working and middle classes.

The authors close the book with a rousing argument that a widely-felt desire for popular democratic control can bind together demands for expansive political and economic reform. They outline a programme based on new forms of public ownership, a more protectionist political economy, the rebalancing of industrial relations, and welfare state expansion, some of which could begin under devolution.

I am personally sympathetic to much of this agenda, but is this a programme that could propel independence to a significantly higher level of popular support than it enjoys at the moment? If the advocates of independence want to win another referendum, they will need the support of the economically secure and the risk averse. The strategic task that this book sets for the national movement is really how to combine the ‘two souls’ of Scottish independence into an effective political coalition rather than to privilege one over the other.

I think the notion that Nicola Sturgeon is aligned with ‘middle-class professionals’ is mistaken. Quite a few middle-class professionals of my generation and aquaintance have been profoundly alienated by her leadership. Her neoliberal allies are quite a different kettle of fish.

Naughty naughty. You pivoted seamlessly from a postulated scenario of the SNP happy to retain power as a devolved government, to accepting that this was the case.

Evidence is what usually drives such discussions.

Political life in Scotland only began in the 1970’s annoys me…..My sister and I joined the local branch of the SNP in 1960….we were following the ideas of Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement….from there we moved to the SNP youth section which turned out to be a useful energy tool for the adult SNP. As long as you did what you were telt seemed to be the order of the day…..

The adult section weren’t really that interested in the Civil Rights movement as applied to Scotland . The Labour Party was their chief target and then everyone got stuck in that political mud for several years.

Same here Alice. We both were supporting independence from way back in the early sixties when you had to have a thick skin to stand up to the detractors. It kind of annoys me that people think the 2014 ref was “the start” of the real campaign.

The Independence movement surely is a river of several streams.

1. There is the very long- established tradition that Scottish kingship (i.e. governance) is based a covenant between king and a sovereign people and not on a divine right to rule. The Declaration of Arbroath demonstrates that a sense of nationhood goes back at least 700 years. (Of course, at that time Norse speaking Orkney and Shetland were still part of Norway and the gaelic speaking Lordship (Kingdom) of the Isles was still contested territory. In fact, one often overlooked fact in Scottish history is that the Lordship of the Isles stands in relation to Scotland much as Wales does to England. Gael and Lowland Scot have been divided and ruled ever since). As the Union of the Crowns approached in 1603, Scotland through the kirk established the Covenant and a firm commitment to a presbyterian as opposed to an episcopal official religion. This was surely a statement of independence mainly by the Scots middle classes as the aristocracy moved to where the power now lay in London, and were encouraged to see themselves as ‘British’ (quasi-English) rather than Scottish. So we can’t really separate the class striuggle from the national one. Contested throughout the 17th c., in the 19th, the landowners attempts to control the kirk through appointments to livings, as they were used to doing in England, brought about the Disruption.

2. Independence has aalways had an economic aspect. The Union of 1707 was massively unpopular and provoked riots. We were, as Burns rightly said, ‘bought and sold for English gold’ – except that it would have been more accurate to say London’s gold, which was already international, especially Dutch. London has always been a state within a state, and even today has a ‘Remembrancer’ sitting behind the Speaker in the House of Commons to make sure the City’s interests are upheld. Scotland was conquered in 1745 by military force and became a colony to be exploited as much as any other part of London’s Empire. The Gaels were treated like native peoples across the Empire to be slaughtered, demeaned as ‘teuchters’, ‘civilised’ , and exploited. The Industrial Revolution saw the creation of an urban proletariat in the central belt, and devastating ethnic cleansing in the highlands. When the industrial scale sheep farming failed the highlands became a rich man’s playground to escape from industrial squalor and go wild, shooting everything in sight – and they still are. As with every other part of the Empire, those who did as they were told were employed in commerce, administration, or the military (‘Tis no great mischief if they fall’). Those who did not were sent off to Australia, Canada, the US, to do their masters’ bidding there.

3. So there’s also an imperial, colonial aspect and also its inevitable counterpart, an anti-imperial, anti-colonial tradition. With the later 19th and early 20th c, industrial Scotland as elsewhere saw a growing revolt against capitalism, expressed in Red Clydeside. Here, the fact that the capitalists identified with the Empire they benefitted from, meant class struggle linked to the traditional sense of nationhood. But the fact the Scotland came to be owned by a small number of ‘British’ industrialists, some of whom like the Duke of Sutherland carried out crimes against humanity, means that the identification of ‘Britishness’ with oppression goes very deep. The Clearances, the Crofter Wars and Crofting Acts have all fed into this bitterness. Keir Hardie had Home Rule as a key part of his platform. What a pity Labour have now abandoned this along with every other founding principle.

4. That takes us to the 1950s, the decline and fall of the British Empire. But the spirit of independence was in the air after the second world war, witness the removal of the Stone of Destiny. The conversion of the Empire into the Commonwealth – where control was (and still is) mostly maintained through debt rather than direct military force – was driven largely by US ‘robber barons’ keen to dominate the world’s economy. That process continues and we are now bought and sold even more than ever for US gold. Brexit too was based on a supposed ‘trade deal’ with the US, that would have locked us even further into a de facto status as a US ‘unincorprated territory (colony). We need our independence from corporate America at least as much as from their corrupt puppet government in Westminster. The Irish had already secured independence from the UK fifty years earlier – apart of course from the then only economically profitable, industrialised bit – Northern Ireland – which the British held onto by fair means and foul. But since entering the EU, it is now the Republic that leads the island of Ireland. Northern Ireland is just an embarrassing and costly rust belt. Would the Republic even want it?

So I do not think it is correct to claim that the independence movement is a recent invention. It has deep roots. Of course, there are always going to be different political views represented in it. There will be neoliberals who think a Scotland independent of London might offer more opportunity for private profit – especially if they suck up to their US masters; there will be radicals who want to see a free anticapitalist Scotland; there will be those who favour a Scandinavian style Scotland (and we do have a Scandinavian history too). And so on. The weakness of the SNP is that it has no unifying ideology. It cannot offer a vision for an independent Scotland because it fears alienating anyone. Bringing the Greens into government was surely an attempt to set a particular path, but all the time there will be those on the right, Tartan Tories, trying to push it in a neoliberal direction. I think we need a new, radical party, that supports independence because it is democratic self-determination, and then proposes a strong, anti-corporate, anti-neoliberal agenda. I do not think that concepts of ‘class struggle’ are useful anymore, now that the ‘haves’ are only 1% of the world’s population and determined to reduce the rest of us to desperate poverty and debt slavery, and so control the entire planet including all ‘human resources’. Is a teacher, a lawyer, a software designer ‘working class’? In the 21st c., the world has changed, life’s too short for a ‘class struggle’ that betrays us all into the hands of those who would divide and rule us. We need a future based, like nature, on mutual aid, not competition.

So who’s up for a new party? I think it could be really successful. People are tired of lies, greenwashing and so on.

Exactly so!

Decoupling socialism from nationalism would be a good start, seeing as they are two seperate subjects unless you have your heed up yer arse.

Yes, civic nationalism (to which the SNP currently appeals in contrast to the now unappealing ethnic nationalism of its past) is essentially a ‘class-transcendent’ liberal phenomena.

I think that a more accurate description of that fake PR drivel is ‘corporate and government-quango nationalism’. Or maybe ‘shampoo nationalism’.

No, civic nationalism is definitely an essentially liberal phenomenon. It appeals to traditional liberal values of freedom, tolerance, equality, and individual rights, and doesn’t distinguish any differences between the various identities of the citizens that comprise the nation qua citizens. And the SNP definitely promotes civic nationalism in its rhetoric, affirming that ‘Scottishness’ is to be defined not by blood or cultural heritage but by voluntary participation in its civic life.

But you’re right to raise doubts about the SNP’s commitment to democracy. It’s current leadership shows a penchant for bureaucracy over democracy, entrusting public decision-making to government functionaries rather than to the citizenry itself. One would hope that a returning radical independence movement would include a demand for greater democracy as a condition of that independence; otherwise, what would be the point?

‘If the advocates of independence want to win another referendum, they will need the support of the economically secure and the risk averse.’

Indeed! ‘Middle Scotland’. Which is why the current SNP leadership don’t want to ‘frighten the horses’ except by amplifying the risk of remaining with the status quo. In pursuit of independence, it needs to pursue policies and conduct government in ways that appeal to this majority and its interest in consolidating and extending its security. ‘Radical’ talk of UDI, the redistribution of wealth in support of greater environmental and social justice, repelling ‘intruders’ who threaten our indigenous ways of life, etc. is hardly going to appeal to this essentially conservative (with a small ‘c’) majority.

Perhaps, as a coalition of minorities, the radical independence movement’s ‘time’ will come only after independence, when it might advocate in a much smaller political pond for its various radical proposals against the conservative mainstream of Scottish society.

Prudens qui patiens – softly, softly caught the monkey.

Support for the SNP rose steadily through the 1960s and early 70s, doubling at each succeeding Westminster election, reaching 30.4% in October 1974. 30.4% is significant support 40 years before the independence referendum.

There are numerous potential reasons for this rise in support including the loss of empire largely by the early 60s, the loss of economic autonomy caused by widespread nationalisation leading to centralisation of control in London, and the discovery of North Sea oil as a powerful antidote to the ‘too poor’ claim.

Something that doesn’t get much attention is the change in the psychological environment in Scotland of constitutional politics brought about particularly by the creation of the new parliament, but also the change from ‘Executive’ to ‘Government’ in 2007 and what went along with that. Perhaps you also have to be of a certain age to appreciate just how much of that is the achievement of Alex Salmond, a man directly described by the author of this article in terms he should be ashamed of.

John Wood ,that is the best piece I have ever read to explain the frustrations of the Scottish people and to point the way forward for us ,thank you.

Thank you Ben for an excellent review. I have not read the book, will do so now.

One problem with characterising the independence movement primarily as a rebellion against the neo-liberal order that emerged after the 2007-8 financial crash is that it does not explain why that rebellion took the specific form it did in Scotland, which is so different from that which has emerged in England. It seems to me that the underlying reasons for this stretch further back and, critically, relate to the democratic deficit within the UK, and the emergence over the long term of different majority political orientations in the two countries. It seems to me that it is that tension that drives the independence movement, which is at its heart a movement for greater democracy. I look forward to finding out in greater detail how the authors relate to these issue.

One problem with characterising the independence movement primarily as a rebellion against the neo-liberal order is that it isn’t even vaguely a rebellion against the neo-liberal order. The 2014 campaign mostly played to the appeal of personal and corporate greed, and I don’t think that has changed at all.

The radical and very unpopular fringe campaigned to be radical and very unpopular in an independent Scotland.

Most people I know who votes yes did so because they hate the UK government and everything it stands for, I’m willing to bet you could extrapolate that anecdote pretty far, consciously “radical” or not (mostly not)

Indeed! The Scottish government has successfully milked our dissatisfactions, making ‘Yes’ a vote *against* the Tories rather than a vote *for* anything progressive. In any future ‘déjà vu’ referendum, we’ll know what we’re voting against if we vote ‘Yes’, but not what we’re voting for.

This article may be interesting but does not acknowledge the reality of achieving independence.

The 2014 post independence referendum analysis showed the biggest difference between No & Yes voters was having a mortgage. In light of this the prospectus outlined above is hardly likely to appeal to the approximately 20% Soft No’s that need to be convinced to vote Yes.

This article is putting the cart before the horse – independence first as a matter of principle with honesty about challenges and opportunities that it will bring.

Once the country is independent then the arguments about the political direction of the country can really become. Based on all electoral data of last 50 years we can say that:

there is less chance of a right of centre Conservative type party gaining power than under current Westminster system

the radical prospectus would have more chance of succeeding electorally in an independent Scotland than in UK.

Ultimately the decisions on what political direction the country take will lie with the Scottish electorate and I for one am now happy with this despite being previously opposed to independence for many years.

Your contribution is refreshing because there has been virtually no recognition that how people voted and will vote in the future is very personal. For most folk it’s how their financial position will be affected.

As in 2014 mortgage lenders have huge mortgage books in Scotland they will not want to undermine the value of that commitment.

Lenders like lending in Scotland. Although they don’t publish separate details for Scotland as regards mortgage repossession . Speaking privately to their arrears managers Scottish bad debt proportionately was much less than elsewhere in the U.K. during the Credit Crunch.

This article refers to ‘The Return of Radical Independence ?’ It is worth considering, return from where ? R I C was prominent in the run up to the 2014 referendum. However, when it contested the 2016 Holyrood Election – in partnership with the Scottish Socialist Party – it fared very badly.

That election demonstrated the core weakness of the Scottish left. It lacked, and lacks, a direct connection with voters.

Whether Scotland’s pronounced antipathy to Toryism is due to the de-industrialization of the 1980s or to more recent events is interesting but not likely to engage with voters who show no interest in the left’s economic agenda.

The question is; will voters show more interest in the left’s policies than they did in 2016 ?

The lack of any visible traction achieved by the socialist left in Scotland since 2014 is indeed surprising (and, in my opinion, disappointing). It is also largely un-analysed by the same socialist left, who seem to be much more comfortable with criticising the SNP than developing any genuine connection with those they aspire to speak on behalf of. At the same time, these same critics often seem nonplussed by the Scottish Greens, who have been rather more successful in establishing a meaningful presence in Scottish politics, and who are much part of the radical wing of the independence movement.

The Scottish left hasn’t had any traction since 2007 when the SSP melted. The Greens are part of the government, so we can plainly see exactly how radical they are. As far as I can make out that stretches to radically delaying the introduction of a bottle deposit scheme.

Does government always need an “-ism”?

Seems to me that rule by ideology always sucks. The world is redefined to fit the “ism” of the ruling party. Reality is bent out of shape to conform to the picture painted by each politician.

Could we not have a party that believes in a rational, long-term evolution towards creating a society that produces the greatest, most widely spread store of health, wellbeing and survivability? A series of citizen-led conversations to make policy. An acceptance that power should be distributed as widely and as far downward as possible, in order to create resilience and a move away from specialism and dependency on single resources (e.g. oil)

I’m sick of the same old shit.

‘Does government always need an “-ism”?’

Yes, because, in our broader Western culture, we like to distinguish and classify; that is, to name things. The practice stems from the superstition that, if we have something’s name, we have control over and protection against it. Naming is how we tame or domesticate the world, bring it under our dominion.

What you are looking for is an ecologically-minded social democracy (Dreaded ideology Im afraid), what you are living in is a world built and ruled largely by people who operate according to principles they sincerely believe are “non-idealogical” (market laws) and sincerely believe they are above “-isms”.

Spot on, Blair! And one of the ways of giving the lie to this ‘naturalism’ (‘it’s just the way things *really* are’) is to unmask its genealogy, its line of ideological descent.

Everything is ideology; there’s no escaping it.

I agree very much Wul and look forward to the emergence of exactly such a party