The power of self-organisation: Stuart Christie and anarchy in the UK and beyond

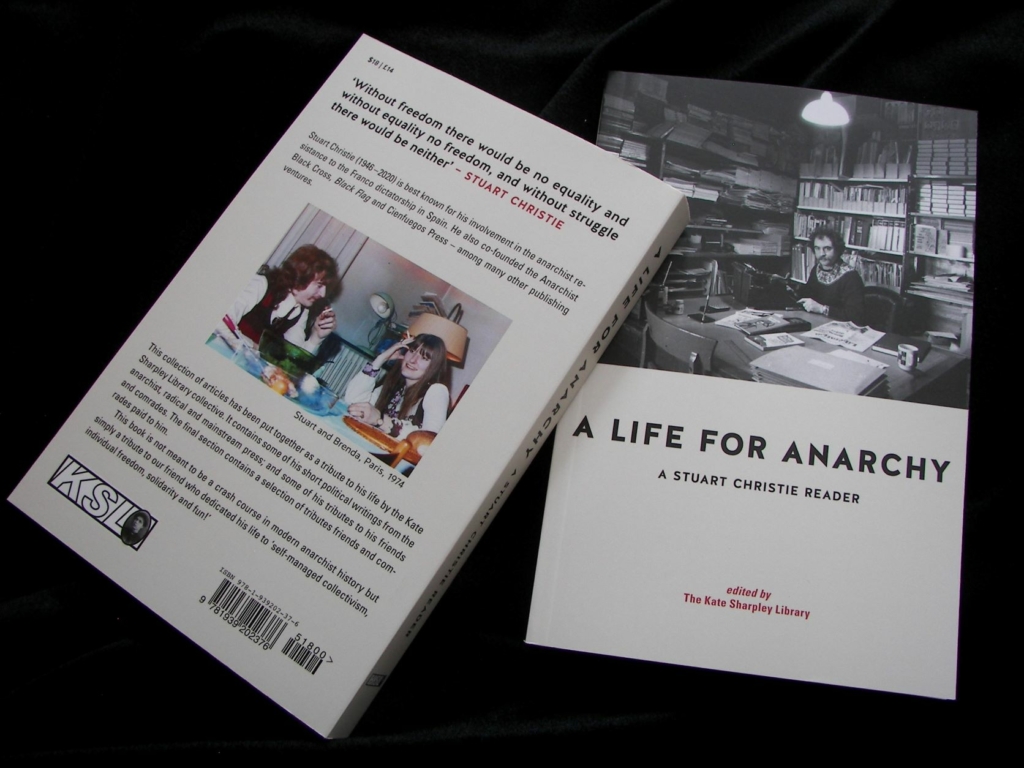

A Life for Anarchy: The Stuart Christie Reader is published by the Kate Sharpley Library in collaboration with AK Press. Reviewed by Duncan Campbell. As we wrote in 2020 ‘He was undoubtedly the most influential Scottish anarchist of the 20th Century.’

If you walk along Fleet Street in London and look up to the first floor of number 88 you will see a stain glass window featuring a handsome kilted figure. This is Stuart Christie, created by the Glasgow stain glass artist, Keira McLean, and the building is that of the May Day Rooms, the archive centre which is now housing a room named after him and a collection of anarchist material that has been assembled since his death in 2020.

To coincide with the launch of the archive this year, A Life for Anarchy, A Stuart Christie Reader, has been published by the Kate Sharpley Library (KSL), the California-based organisation named after the young anarchist who, as a 22-year-old, at a royal presentation event in Greenwich threw the first world war medals won by her late father, brother and boy-friend at Queen Mary, with the comment: “if you think so much of them you can keep them.”

Stuart Christie is, of course, best known as the person who, in 1964, as an 18-year-old from Blantyre, hitch-hiked to Spain from Paris with explosives given to him by exiled Spanish anarchists with the aim that they would be used to assassinate the dictator, General Franco. He was arrested in Madrid, the whole operation having been infiltrated from the start, and faced a possible death penalty by garrote vil before being sentenced to twenty years imprisonment. Inside Carabanchel jail he would meet many others who had risked their lives to oppose Franco, many of whom would become lifelong friends and who feature in this book.

He served only three years before being released but soon afterwards was arrested in London and accused of being a member of the Angry Brigade which had been carrying out a series of small bomb attacks aimed at political targets. He was held for more than a year in prison until a 1972 Old Bailey trial at which he was acquitted, having given evidence that the police had planted two detonators in his car. Four co-defendants were convicted and jailed. Having being warned by a Special Branch officer that if he stayed in London he would risk further arrests, he moved first to Yorkshire and then, in 1976, to Sanday in Orkney where he set up Cienfuegos Press, one of his many publishing ventures which gave voice to anarchists around the world.

A Life for Anarchy is essentially a compilation of Stuart’s writing over the last half century which has appeared everywhere from the anarchist publications, Black Flag and Freedom, to the Times Higher Education Supplement and from what was then the Glasgow Herald to London’s Time Out and City Limits magazines. There are also contributions from those who knew Stuart from his days as a teenage rebel to his later roles as editor, publisher and author. His own very entertaining and self-deprecatory memoir, Granny Made Me An Anarchist, was published in 2005 and is an essential companion to this book.

The introduction by the KSL collective makes it clear that Stuart did not let the thwarted bomb plot define him. “The failed attempt shone a light on the Franco dictatorship and Stuart came to believe that the ‘law of unintended consequences’ meant that his arrest was the best possible outcome…Without Cienfuegos Press and Stuart’s other publishing efforts we would know much less about anarchism. Who would have given voice to half of those lives and ideas?”

Stuart’s obituary of Franco, which appeared in Freedom, the anarchist fortnightly, in 1975, also places the attempt in context. It is a timely reminder as more and more evidence emerges, through the discovery of mass graves, of Franco’s vengeful brutality long after the Spanish civil war had ended. “As Franco decayed and rotted on the death-bed he could see his empire decaying too. Perhaps in a last vision of dreadful clarity he saw his achievement without illusion for what it really is: a period of death and disaster, catastrophe and ruin, fear and agony brought upon a people for no other reasons than that they failed to free themselves from Army rule…Death has been the major achievement of Franco and his cohorts. Now it takes him too.”

While in Sanday, Stuart and his wife, Brenda, also started a local alternative paper, the Free-Winged Eagle. In its first edition in 1979, Stuart explains its title as coming from a poem by the Mexican anarchist, Ricardo Flores Magon:

“We cannot break our chains with weak desire/With whines and supplicating cries/’Tis not by crawling meekly in the mire/The free-winged eagle learns to mount the skies.” He urges his new readers to come up with their own contributions but warns that “anything in support of a political party, bureaucratic body or obescurantist organisation will find its way straight to the the waste-paper basket. Reviews, poetry, illustrations etc will also be considered welcome. What better way to spend a cold winter’s night than sitting by the peat-fire’s glow with a jug of home-brew, writing the odd page or two for the Free-Winged Eagle!”

Stuart maintained contact with many Spanish anarchists and his obituaries of them appear here. Of Luis Andres Edo, with whom he shared a cell in Carabanchel, he writes: “I had just turned twenty at the time and in fact it was he who first taught me how to shave … I often recall with pleasure the lengthy discussions we had each evening after lock-up until ‘lights-out’ in which we seemed to cover every conceivable subject under the sun. Many of these strands of thought he dedicated to fine onion paper in miniscule hand which we later smuggled out of prison.”

His obituary of Miguel Garcia suggests that his life was an example of what anarchism should be in practice: “not a theory handed down by ‘men of ideas’, nor an ideological strategy, but the self-activity of ordinary people taking action in any way they can in equality with others, to free up the social relationships that constitute our lives.”

Amongst the many reflections about Stuart from other writers is one from John Barker, who met him first in prison as a co-defendant in the Angry Brigade trial, who was convicted and jailed for ten years and whose own memoir, Bending the Bars, was later published by Christie Books. “I miss him and his final ‘Toodleoo’ at the end of a phone call,” writes Barker. “I hope, too, that he, by his life, makes clear that is not some ‘natural course of things’ that one loses one’s youthful revolutionary commitment rather than, as in his case, constantly finding new ways to express it.”

The writer, Pauline Melville, is quoted as saying that Stuart once sent her photos of Mexican gravestones, one of which she felt might be relevant to him: “Rest in Peace. Now you are in the Lord’s arms. Lord, watch your back.” Jessica Thorne, who expertly assembled the archive now in the May Day Rooms, recalls Stuart as “iron-willed, yet self-critical.” There are also contributions from Stuart’s Spanish comrades. A rich piece of writing by Xavier Montanya, translated by Paul Sharkey, suggests that the quotation that summed him up “to perfection” was from William Kingdom Clifford: “there is only one thing more wicked than the desire to command and that is the will to obey.”

The journalist Ron McKay, who first knew of Stuart when his reason for appearing in the local Lanarkshire press was the length of his hair, recalls how when asked how he was, Stuart would always say things were “Tickety Boo”. And what better way to describe this rich, rambling, informative volume, with its many illustrations and cartoons, than to say that it is indeed just “Tickety Boo” – even if you don’t have a peat-fire’s glow to read it by.

‘…“not a theory handed down by ‘men of ideas’, nor an ideological strategy, but the self-activity of ordinary people taking action in any way they can in equality with others, to free up the social relationships that constitute our lives.”’

Precisely! That’s the end of ‘negative dialectics’ as an intellectual strategy: nihilism; the deconstruction of all theory, which chains the human spirit within its media of meaning and value, and frees that spirit to spontaneous growth in unmediated community.

‘…”anything in support of a political party, bureaucratic body or obescurantist [sic] organisation will find its way straight to the the waste-paper basket.”‘

I like this.

‘”What better way to spend a cold winter’s night than sitting by the peat-fire’s glow with a jug of home-brew…?”‘

This I like not so much; it’s far too prescriptive of ‘the good life’. Sitting by the television’s glow with a six-pack of Black Label has as much to recommend it by Christie’s ostensible standards.

Thank you for sharing this reminder of such a great man. I’m glad to hear his writings are gathered and preserved for the benefit of others seeking inspiration in a vision of the world that puts equality and freedom as foundations for a healthier world.