Understanding Zombie Capitalism and the Limitations of the Posh Left

Understanding Zombie Capitalism and the Limitations of the Posh Left: Learning from the Work of Mark Fisher

k-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Work of Mark Fisher, 2004-16, Mark Fisher edited by Darren Ambrose, Repeater Books. Reviewed by Michael Gardiner

There are numerous politically-charged commentaries of popular culture in the UK and overseas, but few have contributed as much originality as those of Mark Fisher, whose writing covered culture, politics, class and tyranny of zombie capitalism.

Repeater’s huge collection of short writings from across the 2004-16 period by Mark Fisher, reaching over 800 pages, consists mostly of posts from Fisher’s own k-punk blog, but also includes articles from sizeable outlets including Sight and Sound and New Statesman. Compellingly written and highly readable despite the book’s intimidating length, the collection is set out mainly chronologically and reads like a chronicle of the hopes, frustrations, and cultural contests of the times.

The collection stretches from the origins of the k-punk blog during the dreary millennial era, as Fisher was adapting music journalism and the hyper-stimulated tone of the semi-legendary ’90s Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at Warwick University, through reactions to the 2008 banking crash, after which he sees neoliberalism entering a zombie phase, lumbering on as an ingrained set of empty habits, and ends on the introduction to the unwritten yet much-commented project ‘Acid Communism’ (2016).

Editor Darren Ambrose separates his selection into sections, concerning books, screens, music, political writings, interviews, and reflections, but understands these as notional categorisations for a body of shifting, often disorientingly easily, between pop culture, political activism, philosophy, radical psychology, and beyond. A few common touchstones are J.G. Ballard, Franz Kafka, Jean Baudrillard, Frederic Jameson, post-punk, Margaret Atwood, David Cronenberg, Dennis Potter, Stanley Kubrick, situationism, cybernetics, horror including English ‘folk horror’, science fiction generally, and, perhaps most often, primetime TV and chart pop music, but the collection’s concerns are hard to categorise, and typically brilliantly riff off moments in pop culture to wider political question of finding agency in the contemporary moment.

These essays are mostly short and punchy, though often extraordinarily expansive – and Fisher was invigorated by an early 2000s blog scene that, as editor Darren Ambrose points out, inherited the tone and concerns of older music papers like the NME. Music would remain Fisher’s main touchstone, and he was a regular contributor to, and at one time reviews editor for, Wire magazine. This 2000s blog tone, urgent and popular but philosophically backed, would echo on in the Zer0 publishing imprint Fisher co-founded with Tariq Goddard. Early Zer0 books, like Fisher’s blogposts, interweave pop culture, political comment, and activism in a way that might compare to the ‘cultural turn’ characterising the early New Left during a late-’50s moment that was itself trying to break through the ‘time and motion’ realism underwriting the promises of the British post-war consensus.

The uniqueness of Fisher’s voice comes through an ability to meld something like music journalism with an ability to draw back from a moment of pop music or TV to diagnose and historicise a political tendency to open up or close down alternate futures. The rapid attack of these writings builds on early 2000s blogs’ DIY aesthetic, offering editorial freedom and a possible grassroots audience – though Fisher himself is relentlessly attentive to the dangers of self-satisfied obscurantism, and frequently argues for strategies for recapturing the political and cultural mainstream in the name of creative joy and ‘Red Plenty’.

Cross-commenting in this blog community also fostered a new synergy and the high-speed creation of cultural and political collectives; blogs moreover demanded a rhetoric and a popular edge that stood uneasily with some of the high-handed miserablism that had come to characterise much of the British Marxist left. For Fisher the trained philosopher, the blogpost was one antidote to academic writing’s assumptions of exhaustive research, solo writing, slowness to current events, and this understanding of the role of the public thinker continued on to Zer0 and then Repeater.

Throughout the blogposts, then the larger magazine pieces, the crisp and often ascerbic economic prose of the music journo is filtered the sensibility of the cutting-edge philosopher, in diagnostic nuggets that often have pop culture or current affairs as their gateway. This tone of highly committed cultural critique has been genuinely influential on a generation of writers looking for a place between analysis, activism, and cultural fandom (on years of my own students, for example, who, when they got Fisher back to Warwick University for an event on music and politics, found a thinking that was oddly inspirational for someone associated with depression, embodied in an unintimidating, even diffident personality far from the authoritative mainstream of British left journalism.

Challenging ‘Posh Left Moralisers’

Fisher was also separated from much of the ‘professional left’, though, in refusing to let go of class questions, even as class seemed to be eclipsed, in England at least, by an institutional identity-mongering he saw as a tendency to the bourgeois reinstatement of typologising tendencies that activists had struggled over decades to discard. Numerous blogposts are concerned to register how the material conditions of planned precarity, the denial of security and so an ability to grasp personal time, has had a disastrous effect on people’s collective ability to produce challenging culture; economic poverty and aesthetic poverty are closely intertwined.

This dogged attention to then-unfashionable critique of the workings of the British class system finds its highest form in Fisher’s already-classic 2013 essay ‘Exiting the Vampire Castle’, the second last of the excerpts here. The Vampire Castle essay is both a despairing howl at the puritan hostility of much of the contemporary British left and an early critique of what would later be called ‘cancel culture’, which for him tends to amount to shutting down working-class potential using censorious comments by ‘Posh Left moralisers’ in ‘kangaroo courts’.

A vampiric left appropriates the energies of the working class to create ‘a new market in suffering’ – more capitalist realism, and a symptom of the British bind. In blogposts Fisher frequently displays the lived consequences of this market realism through his own class-bound difficulties in producing work and maintaining mental health; removed from his own background in classic British fashion, he nevertheless lacked the confidence to do ‘professional’ work, and spent most of his adult life occupying shaky positions as a freelance writer, researcher, or FE college teacher.

This issue of the material conditions needed for imaginative work, of breaking through the endlessly-repackaged ‘hell of the same’ to create a currently-unthinkable future, is a theme he never lets go, and it lingers on in a number of early Zer0 books which remain crucial documents of the British early 2010s. Cultural and political creativity then has to be understood through zombie capitalism’s appetite for personal time; and repeatedly the blog candidly detailing a grinding struggle to overcome despair in the face of apparently ever-narrowing creative and political possibilities.

In this tendency to personalise, as well as in its sheer range of cultural and current-affairs concerns, the collection crucially tracks how the mid-’00s to mid-’10s period actually felt. To a casual reader Fisher’s stand-alone books have sometimes given off a sense of powerlessness; this is far from his thrust, though, and the wider corpus shows him, even while depicting the apparently inexorable march of semiocapital, refusing to give up on the creation a radically open future.

Indeed in blogposts especially Fisher rails against elements in the establishment left propagating a debilitating fatalism, shutting down the possibilities for alternate thinking that depended on working-class energy, creating cultural capital out of despair, and ultimately complicit in shutting down creative free time for those in more precarious positions.

Whatever happened to the project of creating a different future?

Recreating the conditions for the possibility of a ‘new future’ then requires this constant struggle, on the dual ground of the material and the imaginative. Thus the final project of ‘acid communism’, a phrase that drew a lot of attention at the time and has predictably sometimes been misrepresented – psychedelic drugs were only one historical externalisation of a wider tendency Fisher understands as an imagination radically open to non-realist possibilities and to the enjoyment blocked by capital.

The possibility of working-class free time is again crucial to this, and is re-examined in post-war movements including what he sees as a much-maligned ’60s subculture. Where time and attention are increasingly taken over by realist beliefs about productivity as personal fulfillment, the possibility of imagining a life beyond labour can come to seem bizarre; the ‘psychedelic’ in this sense stands for a radically open imagination, a spirit of generosity, and the willingness to think beyond a narrowing realism.

Other blogposts had extensively described the alternative to be escaped – the critique for which Fisher is probably best known, the addiction to retro and repackaging in music and other culture, and the diffusion of labour time to break up solidarity, confidence, and shared memory, a critique more familiarly known from Capitalist Realism (2009) and Ghosts of My Life (2014). Fisher remains attached to the possibility not only of an avant-garde, but more importantly of a ‘popular modernism’, a largescale breakthrough; he frequently and bracingly castigates tendencies to write off utopian thinking, and effectively shows the reader his personal struggle against the disspiriting hold of semiocapital, something seen unfolding over the years here and becoming poignant in the abrupt end of the ‘Acid Communism’ project.

Capitalist realism, he recognised earlier than most, relies on personal dejection and the internalisation of a miserable and all-consuming work life as an inevitable condition. Thus also his crucial comparison of the current British political landscape to the late Soviet Union, one familiar from Capitalist Realism but portrayed even more vehemently in the blogposts: in both situations, a set of official and semi-internalised ideological beliefs have to be constantly performed as totally natural in order to sustain themselves, even though each body and soul rails against their suffocation of liveliness, solidarity, and innovation, desires that would in healthier times be understood as common sense.

Let’s Talk about Britain, England and the Ideology of the Ruling Class

The search throughout is for the possibility of creating newness, and ways to unblock the working class energy he sees as having driven cultural and political innovation. Fisher’s grappling with the ‘death of the future’ has much in common with Franco Berardi and other Italian autonomists, but here has a very British frame of reference, as the studious inertia of the ruling class sees off creative joy – ‘[t]he UK, the first capitalist country, is the world capital of apathy, diffidence and reflexive impotence’. So, tellingly, even as ‘England in 2015’ presents itself as a beacon of freedom in its deregulation of markets and the supposedly classless meritocracy, it is still ‘possibly the most depressed country ever to exist on earth’.

But this era of narrowed possibilities and empty nostalgia was also, as Fisher recognises, characterised by a burgeoning of forward-looking politics in Britain’s northern periphery. Writing about the chummy and empty conversations making up the BBC TV show This Week after September 2014, he describes optimistically how ‘the popular mobilisation after the independence referendum has reversed the trend towards cynicism about politics’. And rightly unfazed by the defeat of 2014, he understands the wider creative possibilities opening up in Scotland that remain, for the moment, ghostly in its southern neighbour – possibilities that have to be squashed by a BBC acting, as he puts it, as ‘Pravda for Market Stalinism’.

The misery of the 2015 general election debates is only punctured by the inclusion of the SNP, Plaid, and the Greens (and at one point he hopes for a Labour-SNP alliance); and the politics surrounding independence means an exit from British capitalist realism, a ‘process of reawakening’. So ‘Scotland, Syriza, Podemos… it’s taken a long while for the significance of these developments to filter through to me’. These 2010s developments are for Fisher the blogger personally animating, part of a visceral as well as intellectual battle to imagine a future, and suggest a shift from fearful political deactivation ‘to the Red of internationalist cosmopolitan conviviality’. Moreover, although much of Fisher’s ‘hauntological’ work quite deliberately considers England specifically – an England not yet swept along by semiocapital’s demands for ‘modernisation’ – in this is the same struggle with British realism boosted by independence debates. It would be great to see a fusion of this powerful collection of insights and the wave of ‘post-British’ writing stemming from, amongst others, Tom Nairn – a figure whose ascerbic, culturally-informed, and passionately committed tone often uncannily resembles that of Fisher himself.

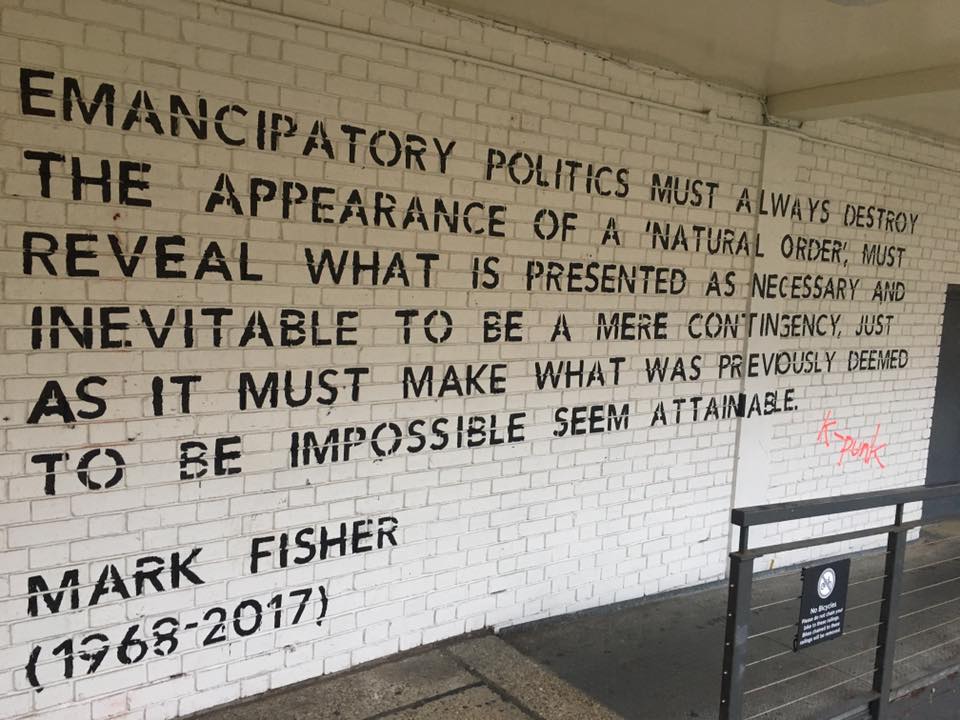

There is as many have pointed out a generosity at the heart of Fisher and k-punk, and at its core a battle to refuse conditions lived as if non-negotiable. In this is a desire to challenge mediocrity and its apologist gatekeepers, political or cultural. Fisher did not have all the answers to navigate and identify the contours of a different future, but he pointed towards integrity needed to undertake that journey.

I’ve a lot of time for Mark Fisher, the eclecticism of his writing, and the philosophical backing to that eclecticism, which he drew mainly from Marxian and post-Marxian cultural theory. There’s a lot of Deleuze and Guattari and a lot of Žižek underlying his output.

Fisher’s stylistic genius is a kind of Nietzschean dance that involved both the ‘high’ culture of French poststructuralism and the ‘low’ culture of Deal or No Deal, and Celebrity Big Brother. It was his postmodernist conviction that all culture deserved the same quality of attention. ‘Good’ culture (as measured by the respect it earns in the cultural marketplace) could come from anywhere, the privately educated Oxbridge bourgeoisie, or the streetwise inner-city Lumpenproletariat. ‘Bad’ culture, which deserved lengthy denunciation and all the resources of Mark’s eloquent contempt, could likewise come from anywhere.

His writing also has an immediacy that refuses to get sucked into suffocating academic writing of what he called the ‘grey vampires’. He could do the academic mode, as evidenced by the papers and essays he contributed to ‘high theory’, but he preferred the more transparent k-punk style that reflected his belief in a more democratic access to thinking. Academia, he believed, is an institution that’s structurally geared to excluding the most of us from thinking.

Fisher follows Žižek in calling the ideology that presents itself as the only possible economic and social world (that is, as ‘reality’) ‘capitalist realism’. Capitalist realism induces in us an attitude of resignation toward economic and cultural impoverishment. It engenders the feeling that, since capitalism is just how things ‘naturally’ are, political opposition to it is pointless. This attitude found its expression in New Labour and the centre-left more generally, which offered (and continues to offer) no alternative to capitalism because, since capitalism is ‘real’ (rather than ‘ideological’), any alternative is necessarily ‘utopian’ and vain. Capitalist realism thus ‘cancels’ all possible futures other than itself, including those futures based on a cloying nostalgia for the past.

The hegemony of capitalist realism is only occasionally pierced by fugitive moments of decolonising resistance or critique produced ‘in the margins’ of mainstream culture. Fisher seized on music, books, or TV shows that manifested those fugitive moments of refusal. He had a particular penchant for the cultural products of the late 1970s and early 1980s, which just preceded the period when capitalist realism settled in.

Fisher’s first book, a selection of reworked blog posts, was called Capitalist Realism, Its manifesto statement asserts a public space for intellectuals, located between the ‘cretinous anti-intellectualism’ of the mainstream British culture the ‘neurotically bureaucratic halls’ of sectarian radical culture. Capitalist Realism is the tortured prose of Fredric Jameson disentangled and targeted at contemporary culture. It’s Slavoj Žižek without the performative tics and perverse contrarianism.

I’m particularly taken with Fisher’s critique of the symbiosis of capitalist realism, its ‘cancelling’ the possibility of any future other than a continuation of the current status quo, and mental illness, writing openly about his own struggles with depression while insisting that mental illness is to be understood no so much ‘morally’, as a disordering of individual ‘minds’, than ‘structurally’ as a consequence of the despair engendered by capitalist realism’s future-cancelling. One of my favourite posts in Capitalist Realism is one in which he drew together the writings of Italian autonomist, Franco Berardi, works of radical anti-psychiatry by David Smail and others, and mainstream celebrity mental illness confessionals to unmask the ‘privatisation of stress’ and denounce the ‘magical voluntarism’ of our internalising the pressures of post-Fordist, precarious employment and smart-phone addiction.

Fisher’s writing is a laboratory for an experimental mix of music reviews, leftist and anarchist politics, and emergent cultural theory. It’s partisan, violently disputatious, preposterous, and passionate in equal measure. It continues to stand for, as he put it himself, ‘the legitimacy, the necessity of being judgemental’.