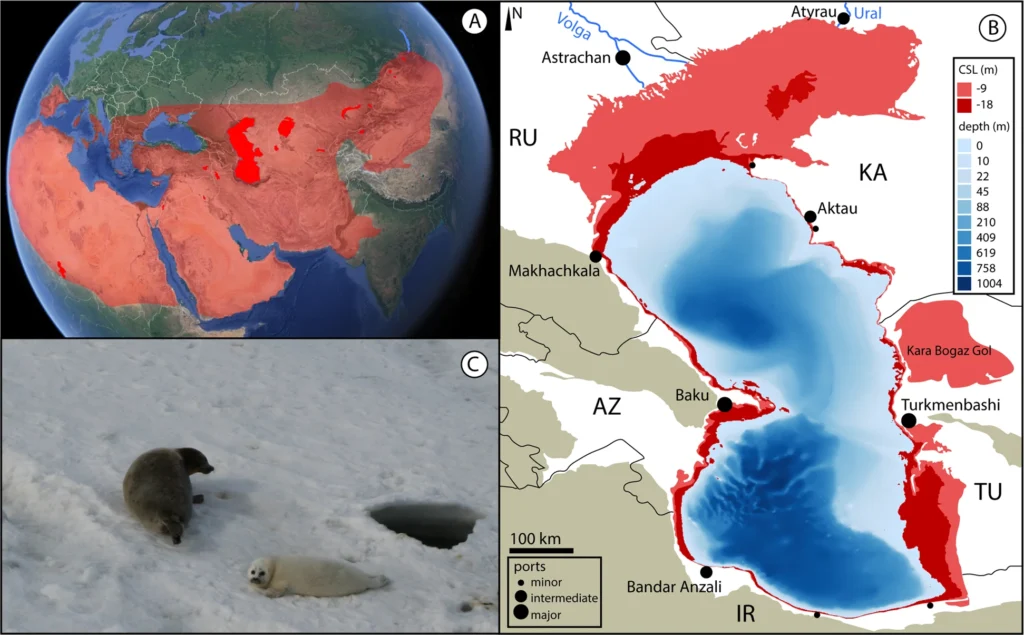

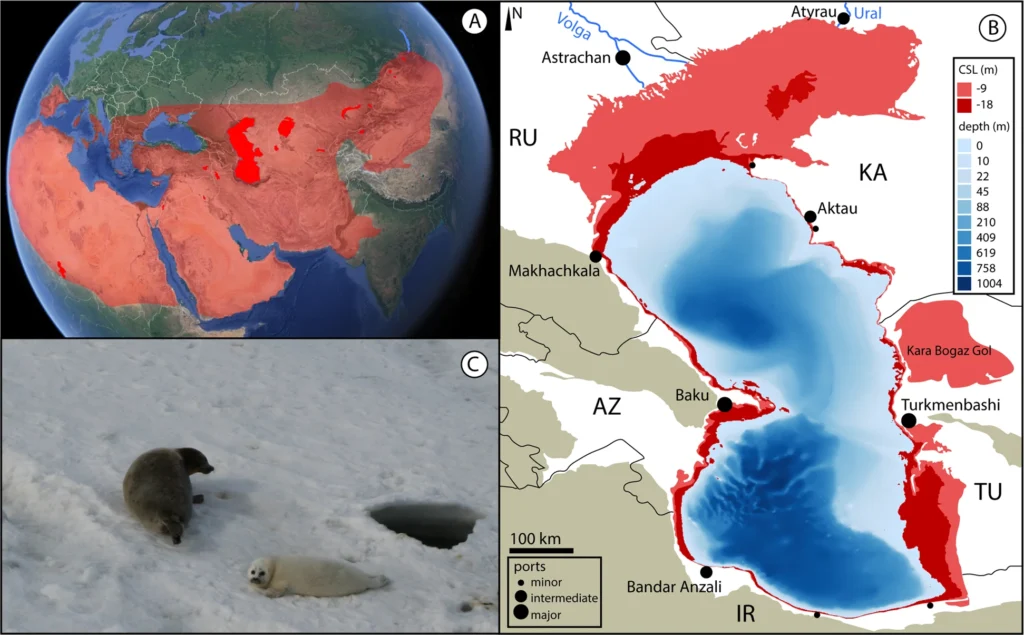

Caspian Sea: how the world’s biggest lake is drying up

The Caspian Sea is the world’s largest inland lake. Today, Caspian Sea’s problems still fall deaf on ears.

More than 100 million people in five states—Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan—rely on the rivers leading to the Caspian Sea. In the decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union, cross-border competition for water, tied with rapidly hastening climate change, has made a poor situation worse.

According to a report published in Nature magazine, by the end of the century the Caspian Sea will drop at least nine metres to 18 metres. Under this scenario, the lake will lose at least 25% of its former size, uncovering 93,000 sq km of dry land. If that new land were a country, it would be an area the size of Hungary.

A continuous and rapid decline in the Caspian Sea level started in 1996, ongoing up to the present day.

Caspian sea level fall and its impacts. A Regions affected by severe drying as projected for 2080–2099 (based on ref. 2) with major lakes located in the region indicated in bright red. Many of these lakes are already experiencing drying. Map data: Google Earth, Landsat/Copernicus (data from SIO/NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, IBCAO, USGS). B Impact of Caspian Sea Level projections of −9 m and −18 m at the end of the twenty-first century. Red regions fall dry. C The Caspian seal is one of the endangered, endemic Caspian species that will be severely affected by the emergence of the northern Caspian shelf and reduction of winter sea ice due to rising temperatures. Today, at least 99% of the pupping grounds are located there (photograph courtesy of Susan Wilson).

Around 85 percent of the water flowing into the Caspian Sea comes from the Volga River, and now, too much water abstraction from the river has left a direct effect on the reduction of the Caspian Sea’s level. Volga, which is also Europe’s largest river, runs through 20 major Russian cities, including Moscow, and there are 11 dams built along this path. The amount of water extracted from the river has notably grown year by year since the end of the last century, which also affects the level of the Caspian Sea to decrease.

The imminent Caspian Sea level decline is threatening shipping traffic inside and outside the lake, which is linked to the World Ocean by the Volga-Baltic Waterway and the Volga-Don Canal.

Dried riverbed, dead fish lying on bare stones – that is today’s picture of Liman, the small harbour town on the southern coast of Azerbaijan. What remain are piers that lead nowhere, the rusting carcasses of boats half-buried in the silt, and white, barren scenes of exposed salt flats.

Today, fishermen in Liman – which is slowly reducing in population – mostly Caspian white fish, bream, pike and sturgeon, the latter often exported.

“We are losing our hope for the future”, says Mehman Guliyev, a 55-year-old fisherman from Liman.

“In the winter, sometimes we will catch about 200 manat worth of kutum (Caspian white fish) per person” in a single catch, explains Guliyev. “Now, we are struggling even to get half of it and as a result, most of us became taxi drivers.”

The situation especially going to affect Kazakhstan, the most vulnerable country, since it has no control on river flows to the Caspian, and coastal regions of the country will be greatly affected by potential desiccation.

In recent environmental disasters in the region, such as Aral Sea and Urmia Lake, the water level decline is due to unsustainable use of water resources caused a lot of public outcry.

The exposed seabed affected by strong winds could cause more dust storms in the region. Studies have linked sustained exposure to this dust to an increase in respiratory diseases in people living nearby.

The challenges involved in restoring and protecting the Caspian Sea’s resources are significant. Given the extensive socio-economic effects, and impacts on human health that may extend beyond borders of five Caspian states, the lake’s bleak outlook requires vigorous involvement of international organizations that can provide expertise and financial resources.

A coordinated effort among the countries in the Caspian Sea is crucial for the implementation of a combined watershed management approach to better understand hydroclimatic changes in the lake, so that improvements could be made to models for better projections of the Caspian Sea level and area.

Policymakers need to mitigate by increasing public awareness about water scarcity, mismanagement and waste may pave the way for re-establishing a balance between natural water supply and water demand.

The Caspian Sea’s shrinkage is not just a tragedy, as many people have said, it is an active hazard unfolding before our eyes. But nature does not make such errors. Human fallacy, on the other hand, knows no boundaries—a lesson that the barren area that once held a great lake should always bring to mind.

Image credit: Nature magazine

I was aware of the severe reduction of the Aral Sea, but was unaware of the effects on the Caspian. In the days of the USSR I imagine the republics would have been compelled to cooperate over water, but, the drive for industrialisation would have had an adverse effect in the longer term, such as the dams on the Volga.

This is not an easy one to deal with.

I never knew about Caspian Sea’s bleak outlook. We must protect Lake Urmiah as well. Great article.

What a good article if a hard read. All of the information (and the daily news of horrific ‘natural’ disasters around the world) leads me to see that the earth’s resources and the future of humankind has to be a priority; not war. Where are the voices that oppose an increase in military spending – time for those who oppose increasing military spending to seek to bring an end to fighting and a serious attempt to negotiate with both Russia and Ukraine – and all of the other countries where our resources are invested in military activities and not in climate security and humanitarian aid. With over 70million refugees, thousands of Russians and Ukrainians dying or dead, aggressive monetary corruption, military might threatening democracy (Brazil today), precarious living for the majority, slavery and human misery the lot of many and an endless list of other examples of inhumanity.

If the armaments budget was transferred to sharing the worlds resources budget and dealing with global warming it would make sense would it not?