Ian Hamilton and the Stone of Destiny: A Lesson for Radicals and Storytellers

Ian Hamilton was never ever an elected politician but is one of the most important individuals to have contributed to shaping present-day Scotland. He was a pioneer, a changemaker and incurable romantic – someone who became a member of establishment institutions but challenged some of the core assumptions and attitudes of that same establishment.

Hamilton played a leading role in one of the great evocative stories of post-war Scotland – the taking of the Stone of Destiny. Besides his many other achievements and longstanding involvement in other causes, it will rightly be the stone for which he is remembered.

Academic Murray Pittock, author of Scotland: The Global History, noted in light of Ian’s death the different ways this episode is still described:

Remembering Ian Hamilton KC who ‘stole’ (BBC, Telegraph, Times, Courier, Paisley Express); ‘removed’ (Mail, Scottish Legal News), ‘took’ (I, Scotsman, Express); ‘swiped’ (Sun); ‘liberated’ (Record, STV); ‘retrieved’ (Glasgow Live, Record). The formation of cultural memory!

Ian was born in Paisley in September 1925 and became active in politics at Glasgow University in the years after the Second World War when it had an energised Nationalist Association. He acted as campaign manager for John MacCormick when he was elected Rector in 1950.

It was this alliance which led to Hamilton’s most famous moment: the taking of the Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey on Christmas Eve 1950. He and three other compatriots – Gavin Vernon, Alan Stuart and Kay Matheson – broke into the Abbey, removed the stone, brought it back to Scotland and made major news and waves.

Scotland and Britain in 1950 was just beginning to emerge from the shadows of war, and there was still a powerful respect and deference for authority and even the British establishment. The removal of the stone was an audacious act which challenged these assumptions, indeed the very idea of a ‘British Scotland’ – and even Britain.

The Stone of Destiny which had previously crowned Scottish kings and queens until it was taken by Edward I in 1296 had long been seen as having huge symbolic significance, and magical and mythical powers, seen by some as bestowing transcendental powers on the monarch coronated on the stone.

The contemporary reaction to the action had many dimensions. Much of the media dismissed it as a ‘student jape’ and tried to diminish and underplay its importance. Others drew attention to the activities of ‘extreme Scottish nationalists’ and their disrespect for British institutions and the rule of law.

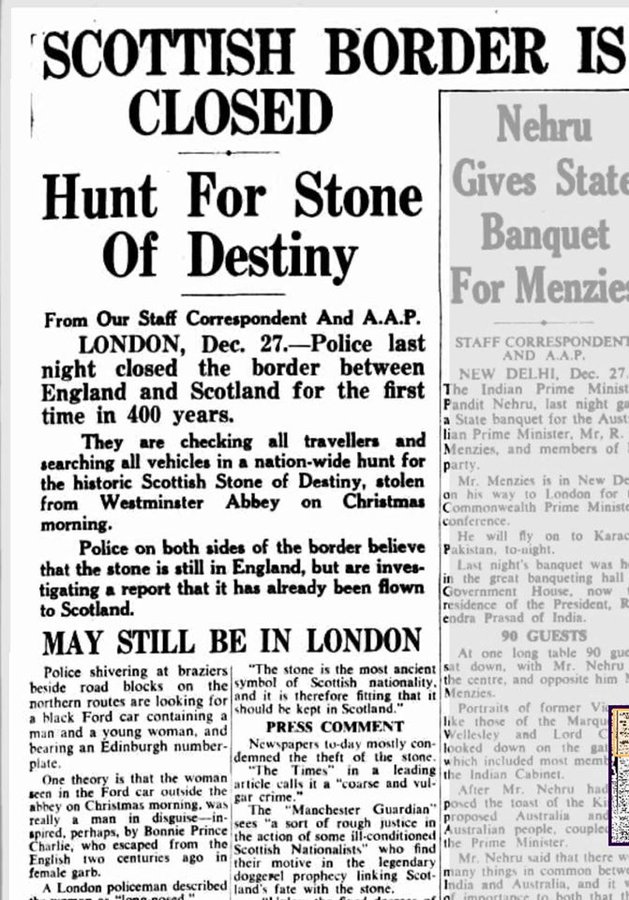

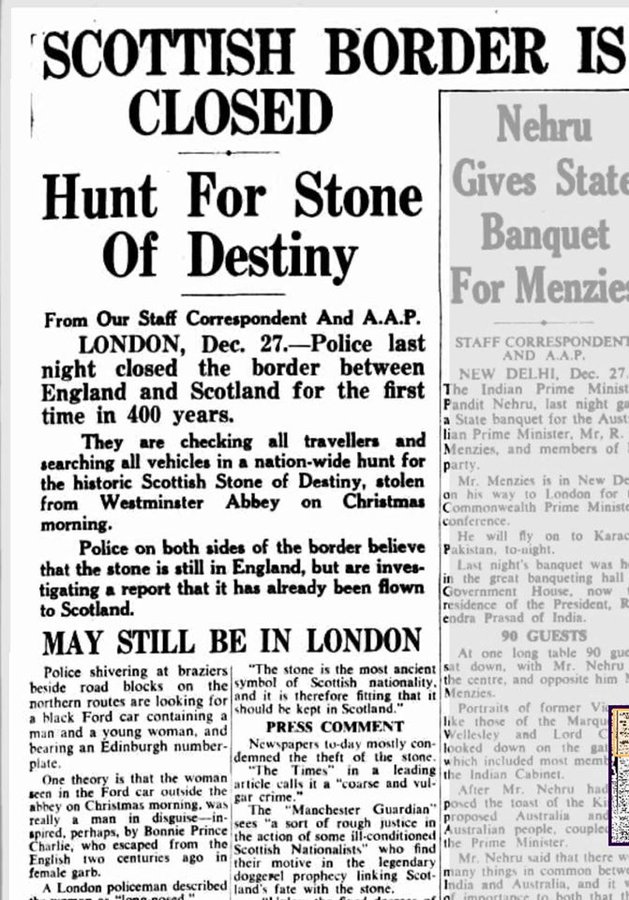

At the heart of the establishment there is evidence this was taken very seriously. In the entire history of the post-1707 union the Scottish-English border has only been shut once: not for COVID restrictions, but in reaction to Hamilton and his friends taking the stone. One newspaper reported this momentous moment on 27 December 1950 with the headline: ‘Scottish border is closed: Hunt for Stone of Destiny’.

The Daily Record reported sympathetically on the episode describing it in its Boxing Day edition as a ‘removal’, avoiding the word ‘theft’, and stating that ‘the plot’ had been carried out by ‘a raiding party’. It quoted Nigel Tranter, one of John MacCormick’s supporters who stated that while the hone rule movement should ‘stick to constitutional methods’ that ‘I would be the last to deplore initiative and enterprise shown by any person in Scotland – even if it is as misplaced as this is – if it will waken people to the feeling in Scotland.’

The Secretary of State for Scotland Hector McNeil took a very different view, calling it ‘mean and atrocious.’ This was a stance echoed in the Glasgow Herald who devoted an editorial to condemning the act: ‘The theft will be deplored by the great majority of Scots’ and concluded with the judgement: ‘the fact that nationalist opinion of the extremist kind has made something of a fetish of the coronation stone in no way excuses the perpetuation of the theft.’

The UK Cabinet of Clement Attlee had several formal discussions on the taking of the stone and a Cabinet paper was commissioned which looked at the different options available to the government. One of these included handing the stone back to the Scots, with the observation being made that to do so could create an imperial precedent of all the stolen bounty in British hands such as the Elgin Marbles.

The authorities were anxious to get the stone back in 1951 as King George VI’s health began to deteriorate and planning was starting for the future coronation of Elizabeth. The stone was left by Hamilton and his accomplices in Arbroath Abbey in April 1951, and no one was ever prosecuted despite it being known who had taken it.

On the 700th anniversary of Edward I’s taking of the stone, in November 1996, a Tory Secretary of State for Scotland Michael Forsyth handed the stone back in a ceremony at Coldstream, with it then residing in Edinburgh Castle. The stone had long ago stopped embodying how power and authority were seen by Scottish people, and any symbolism it still retained could no longer be a substitute for real political power.

After the Stone

Ian was proud of his role in the Stone of Destiny story and happy to be remembered for it. But his life was about much more including one other seminal moment: the 1953 case of MacCormick versus Lord Advocate (the latter representing the Crown), which saw MacCormick and Hamilton go to court on the principle of the name and number of a new monarch in Scotland: Queen Elizabeth – titled II – with no previous Elizabeth I in Scotland.

This was a case which drew on the interpretation of the Acts of Union, 1328 Treaty of Northampton and nature of the Crown and while they did not win John MacCormick and Ian Hamilton did see the Lord President Lord Cooper of Culross declare that ‘the principle of unlimited sovereignty of Parliament is a distinctively English principle and has no counterpart in Scottish constitutional law.’

Ian practiced as a lawyer, became a QC, never giving up on politics, and was briefly a member of the Labour Party, and for much longer, the SNP, standing in the 1994 European elections and 1999 Scottish Parliament elections in Greenock and Inverclyde where he finished third behind Labour’s Duncan McNeil and the Lib Dem Ross Finnie.

I got to know Ian in his later years when he first came to the Changin Scotland weekends I ran at The Ceilidh Place in Ullapool. At one of the weekends myself and Jean Urquhart, owner of The Ceilidh Place, gave Ian what we called a ‘Sorley’ – an award for a lifetime commitment to being a troublemaker and thorn in the flesh of the establishment.

Ian was moved, but at another point in the weekend when we were exploring practicalities of how the then SNP Scottish Government could put obstacles in the ways of nuclear weapons, such detail clearly irritated Ian who commented: ‘Gerry, This discussion is annoying me so much I could give you back that Sorley.’ It was said with a wee glint in his eye, playful, while also showing his romanticism and idealism on the big issues.

A couple of years ago I asked Ian if he would consider giving a quote for a forthcoming collection of fiction, poetry and non-fiction, Scotland After the Virus, which looked at the different impact COVID had on society, and he gave me something wonderful:

What binds our nation is not birth but love. ‘Scotland After the Virus’ has many different interpretations of love of place, people and the connections which make us who we are.

When I thanked him for this uplifting comment he went even further in remarks which I found revealing and moving: ‘It has taken me 95 years of life to have the courage to be able to say that.’

That was Ian to a tee. Always pushing at boundaries. In himself, others, institutions. And in Scotland. When after the above exchange I interviewed him for the 70th anniversary of the taking of the Stone of Destiny at the end of 2020, he was both proud of his role and what he and his friends did, while also wanting to put it in a wider historical context.

Talking of himself, what he did and his life, he told me: ‘My prime qualification was that I did not know my place. I never have.’ Looking back to the Scotland of 1950 and comparing it with the Scotland of 2020 he commented:

Seventy years ago it was a symbol. But we don’t need symbols now, because we’ve very nearly got the reality of Scottish independence. I don’t consider that retrieving my country’s property was breaking the law. After all, the Home Secretary said at the time that we would not be prosecuted. He referred to us as ‘these vulgar vandals’ and that has been one of my favourite phrases ever since.

He concluded his thoughts observing: ‘My generation are handing over something so much better than we inherited. I would like to think the Stone of Destiny played a small part in that.’

In his reflections on the famous act and the ripples it caused Ian in his book The Taking of the Stone of Destiny gave his interpretation of the deep, revealing and emotional ways in which he believed Scotland had changed from the early 1950s to when he was writing in the 1990s:

Nobody sang in Scotland in the middle part of this century. To be more correct, those who sang did not derive their songs from Scotland. Their sources were foreign and what they sang was only an alien copy of other peoples’ ways of life. Now everyone sings Scottish songs, and if I were a unionist politician of whatever party, but especially the Labour Party, I would be counting the songs, rather than the votes. The people who make the songs of a country have a habit of making the laws also.

Ian was one of the standout figures in post-war Scotland who has had a lasting impact on how we see and understand ourselves, our histories and place in the world. One of the major factors about the Stone of Destiny story is that it has become part of the fabric of Scotland – shaping modern Scotland and linking it to the shared memories, folklore and mythologies of earlier generations and the Scotlands of the past.

In this the story of the stone had the added salience that it was told and retold by parents and grandparents, friends, acquaintances and passed down through the years. It had many layers: the obviously political ones, but also some apolitical, just drawing upon that long tradition of Scottish cheekiness and getting one over on the authorities. Ian somehow intuitively understood the need for symbols and stories, and recognised that in his part in the Stone of Destiny he had played a significant role in the journey of modern Scotland.

Ian Hamilton contributed to changing who we are collectively and the stories we tell ourselves. How many politicians and public figures can that be truly said of? And he did so with qualities which combined a radical iconoclasm with playful disrespect for authority and an element of subversion. Those are wonderful characteristics and a lesson for radicals and storytellers in Scotland and everywhere.

Ian Hamilton born 13 September 1925 died 3 October 2022 aged 97.

A fitting tribute.

On the statement “Scotland and Britain in 1950 was just beginning to emerge from the shadows of war, and there was still a powerful respect and deference for authority and even the British establishment.” I wonder if this is a misremembrance of the past.

I have watched quite a few postwar movies on Talking Pictures TV, for example, and I would say they tend to be far more critical of the British establishment of the time than many modern movies. After all, the British establishment had to make signficant concessions not least to forestall rebellion in the armed forces, Churchill’s Conservatives lost the 1945 general election by a landslide to Atlee’s Labour, and ruling parties of either stripe were fearful of popular opinion, as records show, and as British official secrecy strongly implies. The opinions of the lower orders about their officer class was sharpened by unusually close contact during hostilities, the slow demobilisation including mutinies, beginnings of the Cold War, decolonisation movements keen to show up British hypocrisy, and a wider appreciation of just how incompetent yet vicious the British establishment were at waging war. Unrest was hushed up as much as possible, whilst I imagine set-piece public displays of deference were heavily covered by tame media, as they are today.

Does the slavish coverage of the recent royal mortfest suggest that “there was still a powerful respect and deference for authority and even the British establishment” only last week or so? It’s a very general statement that claims impossible insight into minds that may neither be safely inferred from the behaviour of a minority. I understand the temptation is to make your chosen Great Man of History stand out from the crowd.

I once worked with a man who had been a police constable in Edinburgh the 1940s and ’50s. He reckoned that there was a reason for the saturation of the city with police patrols and for each constable’s beat being only a few streets long, that reason being the lack of deference and respect for authority that manifested itself in the level of street-crime that flourished in our towns and cities in those days, an insolence and disrespect that was grimly violent rather than ‘playful’.

Ian Hamilton should have a statue in several streets of Scotland. The Colonial English statues should be removed. That will never happen with the BRITISH F.M. NU-S.N.P. Leader Sturgeon in charge.

Talking of statues where is the one to the Graingers ? you know the Graingers, husband and wife, who rescued and hid the Honours of Scotland

in Edinburgh Castle where they still are on display to-day.

Soar Alba.

The expression is “SAOR ALBA”

Oops !

Aye Iain, yer richt. Thanks, and my apologies.

SAOR ALBA.

The fact that the Honours of Scotland – symbols of monarchical sovereignty – are still on display in Edinburgh Castle is hardly an occasion for national pride. It would have been much better had the Commonwealth succeeded in finding and destroying them, as it had earlier destroyed the English crown jewels. The Royalist, James Grainger, and his wife should be execrated rather than celebrated.

221006. It was NOT the commonwealth that destroyed the English crown jewels. I don’t post to give you 221006/James Mills/ all the other numbers nom de plumes which you use a history lesson. Ge’ aff yer bahookey and educate youself. YOU fool no one except yourself.

The Commonwealth was what Cromwell’s rebels called the republic they set up after the disposal of the monarchy. It ruled from 1649 until 1660, when the monarchy was restored. It’s a matter of historical fact that this Commonwealth destroyed the English crown jewels as symbols of royal authority.

Oliver Cromwell served as the first chairman of the Commonwealth’s Council of State, the executive body of a one-chamber parliament that comprised England’s republican government. During the first three years following Charles I’s execution, however, the Commonwealth was chiefly absorbed in campaigns against counter-revolutionary royalists in Ireland and Scotland. It was during this campaign that the royalist scum, Grainger, hid the Honours of Scotland to prevent their similar destruction by the Commonwealth.

‘ I would be counting the songs, rather than the votes’ – the dramatic cultural shift in music, song and poetry may not be recognised as such by the many brilliant young people now involved in them. It is wonderful.

We need more like Ian Hamilton in the clan. We can ill afford to lose patriots like him.

Watching Sturgeon bow in a truly obsequious manner to Charlie Chimp aka windsor aka saxe coburg made me boke….

The one wonderful part of an excellent article was the headline..’Scottish Border is closed’..my only comment..why the hell did they open it again?

For Scotland!

Great post. Squigglypen. After we get rid of the very BRITISH Murrells, we can erect statues to Ian Hamilton, James Grainger and Admiral Thomas Cochrane for starters. All Scottish heroes. They will replace all English aristocratic statues starting with Gower the master mind of the Highland clearances.

There’s already a statue to Lord Cochrane, Earl of Dundonald, whom General José de San Martín, the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru, dubbed ‘the count of cash’ and ‘the baron of bullion’, due to his grubby mercenary character, in Culross. He’s a strange candidate for your hero-worship; he was hardly an admirable character.

As a descendant of Kenneth I and King Fergus (etc), I understand the spiritual important of the Stone. I also know that our lives can be guide by God. The Stone is not for politics man but a part of the anchor of faith.