Scottish Post Punk and Arts Funding

The guardians of the Scottish Arts have always had an uneasy relationship with one of our country’s most significant exports – ‘Indie Music’ and its similarly Punk-derived iterations.

The highly respected pop-culture chronicler Simon Reynolds opined that, “Indie Music as we know it was invented in Scotland”. During its fledgling years, it was easy to envisage this musical genre as merely a bedroom exercise or short-lived cottage industry, yet it would eventually develop into a behemoth that would make many stripey t-shirted teenage janglers extremely wealthy. Creation Records, the independent label run by Scotsman and superstar impresario Alan McGee, sold far in excess of 50 million records, including the third best selling UK studio album of all time. But despite worldwide critical acclaim and a plethora of skinny kids from Scotland influencing massively successful bands like Nirvana, there has always seemed to me to be a reluctance to fully acknowledge this Scottish contribution to worldwide art within the established Scottish Arts enclave. This music is as much art as anything that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery but it is also something more dangerous – that may hint at a reason for its apparent dismissal.

It somehow seems apt then that the record label which arguably started it all – Fast Product – would begin its life as a series of stickers pasted over Edinburgh Festival posters whose shows had been supported by the then Arts Council. The sarcastic slogan cheekily emblazoned on these stickers stated ‘guaranteed 100% pure art’ which the label impresario, Bob Last later proclaimed ‘was messing around with provocations about challenging classical notions of fine culture’.

It might seem understandable that Edinburgh, the city which hosts the worlds largest arts festival EIF, would in 1977 dismiss the snotty emergence of Punk-Rock, the forerunner to ‘Indie Music’. However it seems perverse that its momentous impact on mainstream art still appears to be treated with some caution here, like an inconvenient nuisance or embarrassing relative. In Scotland from that time until present day, its various creative sub-genres and splinters have rarely entered classical arts culture or acceptance, except by subterfuge – most prominently via ballet’s enfant terrible, Aberdeen’s Michael Clark who sneaked Manchester’s The Fall into his performance of ‘I am Curious, Orange’ at The King’s Theatre during the 1988 Edinburgh Arts Festival. There’s been little else however when compared to arguably less successful Scottish cultural exports such as Opera, Theatre and Film; all receive far more exposure relative to their critical applause and worldwide impact.

This seeming dismissiveness is surprising as it is now coming close to being 50 years since the first Sex Pistols record was released. That legacy has since then unarguably permeated into vast and lingering areas of huge International mainstream acceptance across a multitude of art-forms. Much of this has also proven to be incredibly lucrative, both financially and critically. Scotland has played a large part in this legacy that is still confusingly little lauded at home. While London held a huge year long celebration of these contributions at high-faluting institutions such as the British Library and BFI for ’40 years of Punk’ in 2016, (notably via a £100K Heritage Lottery Fund) nothing remotely similar has happened in Scotland.

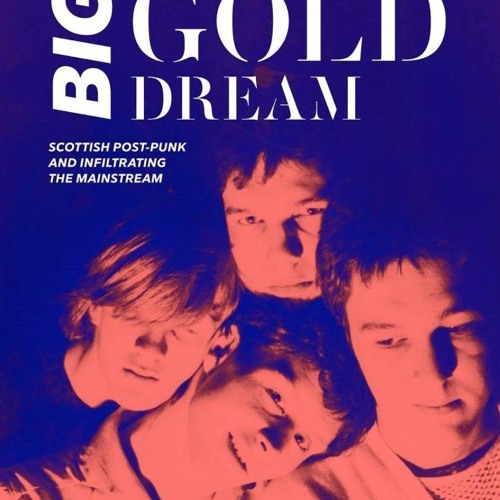

After my 2015 Scottish Post-Punk documentary film, Big Gold Dream was released (more on its partial public funding later), I was approached by The National Museum of Scotland regarding a proposed large scale Scottish Post-Punk exhibition. Sadly, despite a great effort from their fabulous curator, the powers-that-be only gave the greenlight to the exhibition if it broadened its scope to include all aspects of Scotland’s pop. Again, Scotland’s independent music scene was relegated by the funding bodies to a couple of (albeit excellently curated) cabinets at the expense of The Bay City Rollers and chums. This was perhaps almost its only opportunity so far to have received wide mainstream recognition and acceptance within a large publicly funded cultural institution.

While it may seem peculiar for me to expect that a seemingly tiny enterprise which begat ‘Indie’ and was initially run from two small tenements should be given a similar status to Scotland’s significant cultural figures, it should be noted that other cities throughout the UK actually do just this.

A recent trip to Manchester revealed a multitude of memorials prominently dedicated to and celebrating their city’s Punk, Post-Punk and Indie heroes. Huge murals of Joy Division singer Ian Curtis adorn the side of a city block, as does another for celebrated punk icon, Buzzcocks singer Pete Shelley. Factory Records boss Tony Wilson, who was inspired by Edinburgh’s Fast Product, can not only be seen painted across various landmarks within the city’s Northern Quarter, he has an entire cultural area and multi-story building named after him. Although Wilson was initially known as a popular local television presenter, and later a huge part of Manchester’s regeneration committee, it is his musical ‘Indie’ legacy that is being saluted by the city.

In Liverpool too, Mathew Street is not only celebrated as the site of The Beatles most famous musical landmark – The Cavern – it is also the site of Eric’s, the musical venue which birthed their city’s Post-Punk explosion. The location of Eric’s now proudly displays a real Blue Plaque commemorating both the venue and two Punk-related bands that are almost as revered within the city as The Beatles – Deaf School and Echo and the Bunnymen. In East Klibride though, when a mural to its most famous musical export – The Jesus and Mary Chain – suddenly appeared one morning, Banksy style on a subway wall, it lasted approximately 48 hours until the council painted over it.

Why then have Edinburgh, Glasgow and their surrounding towns not highlighted their contribution to this music at a level to other similarly sized cities throughout the UK? It could be suggested that as Scotland never produced a ‘punk’ or ‘indie’ band to rival the success of Joy Division then there should be no need. I believe this view can be countered by considering that while no individual Scottish band reached that same level of success, importantly the infrastructure that allowed Joy Division to attain their legacy had incredibly strong roots in Scotland. It is the creation of those ‘independence’ ideas that helped form the infrastructure which I believe is Scotland’s monumental contribution to ‘Punk’ and ‘Indie-Music’ and I believe this needs to be celebrated just as much as the music. I would also go further and argue that the mechanics and philosophy of the independent music industry’s success should be seen in similar terms to Scotland’s great enlightenment thinkers and engineers. James Watt is not celebrated for only developing a steam engine, he is celebrated for what that steam engine allowed – The Industrial Revolution. Similarly, Adam Smith is not celebrated purely for writing a popular book on economics but what that book would inspire, for good or worse. Ideas spawn revolution.

In addition to lauding great music – and something which simply makes people happy for a few minutes is reason enough to celebrate – I propose that Edinburgh, Glasgow and Government funded institutions should also be advocating the ideas and philosophy behind their city’s Independent Record labels, and the artists on them, as significant contributions to Scotland’s enlightened heritage. By failing to do this to any convincing level dilutes the opportunity to inspire other would-be thinkers and do-ers or for them to see their ideas through to full potential, or worse, leave an amazing idea completely unfulfilled. Scotland is culturally far worse off by not promoting this. While nobody can realistically argue that Fast Product or Postcard Records had a similar impact to the world as the ideas of Adam Smith or James Watt, their ideas are what helped completely recreate the music industry in the late 1970s to considerable financial and creative success. This is a remarkable achievement; simple but radical ideas that were seen through to their conclusion. These ideas inspired and nurtured the predominantly working class musicians who in 1979 were mostly destined for the job centre queue.

However, some of those radical ideas are not always conducive to the politics of Arts funding, and this is where we start to see the possibility for the arts establishment needing to distance itself. It’s easy for a city to retrospectively extol the physical success of an artist – record sales and reviews as a means of quantifying worthiness in a musician, or easier still, for the physical value of a painting in classical terms. However, if ideas pose a threat to how the current arts funding operates, then there will be a likely conflict of interest. I believe this conflict is one of the reasons which, like a slow-moving perfect storm, has resulted in 45 years of mostly disinterest towards this music and its surrounding ideas being properly accepted by purveyors of the Scottish Arts and councils.

Of course, this lack of recognition could just be as simple as the cultural guardians having terrible record collections – which they invariably do – but I’d argue that the lack of recognition for this music, the ideas behind it and seeming disinterest to promote them by arts funders – except without reference to the arts funders themselves – goes back to the very origins of Fast Product and the arts funding institutions it mocked. Fast Product was a danger and a threat to these institutions as its raison d’etre extolled the fundamentals of the perceived threat: doing something for yourself and successfully operating without established control or support. The ideas that underpinned Fast Product formed the basis of the biggest threat to the record industry until the arrival of Napster: the independent record label.

Independent labels had existed previously but were arguably not truly independent as they relied upon major labels to manufacture and distribute their product for them. While Andrew Oldham’s Immediate label can be seen as the ‘Indie’ template in terms of attitude, ideas and style, it was still distributed by The Majors. The ‘anyone can do it’ ethos of the 1976/1977 punk explosion, in real terms mostly only extended to playing live. When it came to recording it was still huge establishment record labels and recording studios that were responsible for the public buying and hearing music. This was fine when a band wanted to sound like The Clash because the rebellious record buying public then had an appetite for bands sounding like The Clash, and as the labels liked making money it was an easy marriage of convenience. Everyone was happy.

However not all groups which formed after that first punk wave made music which subscribed to the notion of the ‘anyone can do it’ 3 chord thrash beloved of newspapers, CBS, EMI, and even the major distributed indies such as Stiff. While an unconventional band could easily be heard in a music venue they could not be so easily heard at home. Inspired by a Buzzcocks self released EP called Spiral Scratch and Socialist manifestos exclaiming the workers to ‘seize the means of production’, many of these genuine outsider bands were compelled to self-release their own singles. What made some of these self releases so dangerous for ‘the establishment’ was a small number contained instructions in order to inspire further bands to also do likewise. Early singles by Desperate Bicycles, Swell Maps and Television Personalities all had sleeves adorned with intriguing references to studio hire, printing costs and pressing plants; Scritti Politti took this rebellion one step further by actually releasing a photocopied complete ‘How to Make a Record’ guide. For the first time, musicians were not just self releasing records as vanity projects they were making their own records for idealogical reasons. Some of the UK’s most exciting, interesting and inspiring music came from this insurrection.

Much like The KLF’s 1989’s book ‘How To Have A Number One The Easy Way’, the mechanics of the record industry was then a closely guarded secret. The internet did not then exist so learning how to make your own – actually real – record was understandably liberating, daring and completely revolutionary. However, making something that does not sell more than 100 copies is not really much of a threat or revolution. The behemoth of the UK record industry paid little initial attention to this attempted infiltration of the mainstream because there was no easy means for them to sell bucket-loads of records. This was strictly still the bedroom cottage industry where many of the fabled anecdotes beloved of music documentaries began such as proudly describing band members folding and packaging their own record sleeves. Shortly, this home-spun factory was to change.

Within this atmosphere of new enterprise and infiltration, actually right at the very beginning, Fast Product progressed from their Scottish Arts Council baiting to create not only their own self-released record but to then take the concept one step further and create their own self-made and self-distributed record label. From that bold move they quickly proceeded to sign some of the most exciting and groundbreaking bands heard in venues all around the United Kingdom. Of course, self-distributed record labels had existed prior to Fast, almost exclusively dealing with locally made traditional or ‘Progressive’ music and forced to rely on mail-order to reach the public. However, the goals for Fast were impressively focussed beyond this. Bob Last still states that one of the primary purposes of Fast Product was not to be parochially Scottish but to show the world that an outward looking operation could be run internationally from Scotland.

Edinburgh’s Bruce Findlay had experimented with a small distribution network for independent singles through his Scottish based Bruce’s Records chain. The real great step forward for independent record labels reaching a significant portion of the public was the establishment of a venture called ‘The Cartel’, the brainwave of Richard Scott from London’s Rough Trade record shop. Richard’s simple plan to solve the decades’ old distribution problem was to create a large-scale network via the thousands of independent record shops. Like most great ideas it was simple and called for each of these shops to swap and stock records by bands from every city and town throughout the UK. This allowed a 7” single from Liverpool to be made easily available in a record shop in Bristol, London or Manchester and so on. Fast Product, who began their label at precisely at the same time as Rough Trade and shared similar anti-establishment philosophies, became the obvious choice to become The Cartel for all of Scotland. Add radio DJ John Peel and weekly music papers into this new mix and the fundamentals of the record industry in the UK would amazingly be forever turned on its head by a simple but powerful idea.

The success and effectiveness of this DIY venture cannot overestimated. In 1980, Depeche Mode’s completely independent New Life single on Mute Records entered the UK top ten at one of most lucrative times within the mainstream record industry. This was a 7” recorded, released and distributed entirely independently and reached a level of chart success that huge industries with their legions of PR and A+R folk could barely achieve with their infinite bags of money and hype. Depeche Mode’s success was achieved by DIY means with a dangerous self-empowering idea. In the context of films this is the modern equivalent of somebody shooting a movie on an iPhone, uploading it to YouTube and it then outperforming the latest Marvel superhero release.

With the exception of The Beatles, for the first time, musicians were being offered the ability to record, release, distribute and promote their own music on mostly their own terms to often huge success by short-circuiting tradition and control. Of course, selling so many records and achieving significant chart placings by breaking those ‘rules’ would quickly draw the eye of these labels. Signed to CBS, The Clash gave their approval and would name check Fast and the fear other Indies created in majors for their 1980 single, Hitsville UK.

Established Arts Funding and Record labels share much in common. Record labels exist by feeding off artists for profit and when they see youngsters offering their pocket-money to small label impresarios instead of them, they want a piece of the action. Or all of it. Similarly, Arts Funders fundamentally need artists in order for them to exist. Record labels need artists to sell music to maintain their business and pay staff, and so do arts institutions. The record industry responded to the DIY threat by aggressively taking large elements of lost control back: at first offering distribution to the ‘indies’, or even simply offering to buy the labels from them, and if that did not work, simply setting up their own rival ‘indie on a major’ imprints.

Arts Funding is based on an assessment of risk, control and structurally promoting its own successes in order to maintain its own existence. Arts funding is not the product of philanthropy, it is huge business – just like the record industry – with staff to pay and jobs to justify and maintain. Arts funding is the antitheses of Doing it Yourself. They don’t require artists to be Independent, they need artists to be dependent – on them. If an artist makes a success independently of a relevant public funding body then that institution or organisation struggles to justify its reason to exist. Ideas, or movements that allow an artist to create success for themselves and on their own terms, or without controlled public funding is the antitheses to how public funding institutionally operates. I’ve personally found that much of our current Government funded ‘talent and development’ schemes centre around ‘talent labs’ and masterclasses that seem to benefit the administrators and guest speakers being put-up in fancy hotels far more than the ‘new talent’. Occult or esoteric information is slowly controlled and drip-fed rather than freely given.

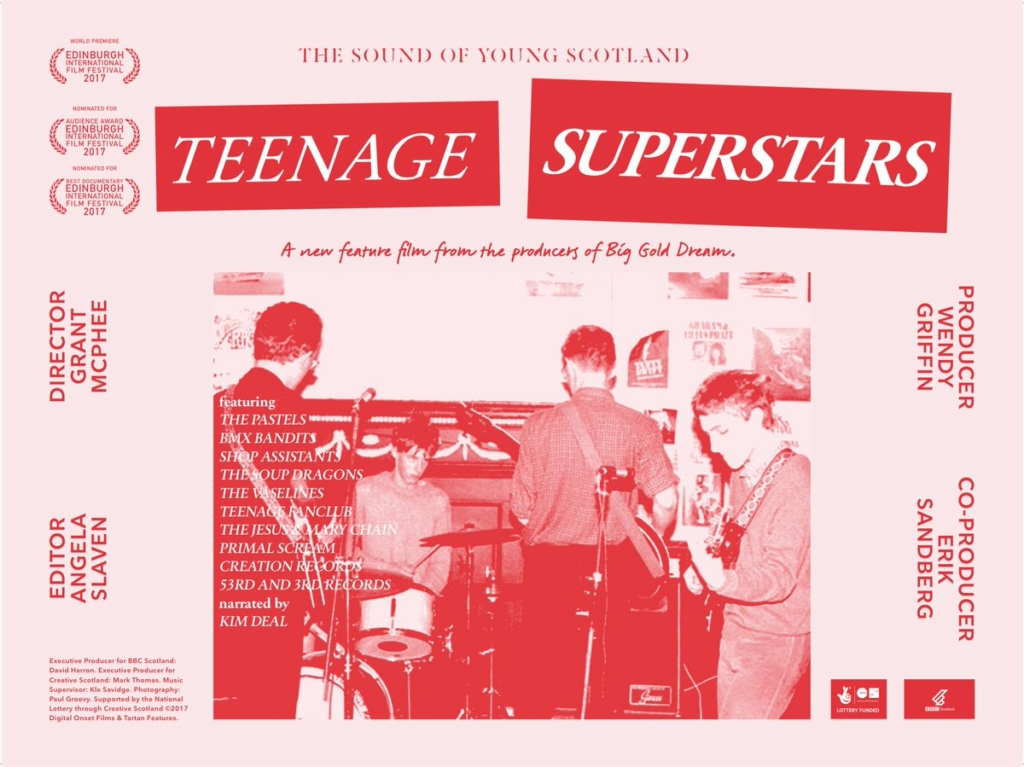

It would be naïve and disingenuous for me to suggest that the only reason I think that ‘Indie music’ from the late 1970’s and 1980’s is not adequately celebrated by Scotland’s cultural bodies is due to some arts institution being scared of the artists taking control. I do believe however that an element of this thinking has taken shape within Scottish Arts over many years and that it is to the detriment of mainstream success for artists wishing to operate under their own terms. As time has often shown across the variety of arts, it is those artists working outside of the mainstream that often produce the most interesting and long-lasting work. A quick look at the webpages of Creative Scotland, Screen Scotland or the various schemes they fund show they invariably only promote what they fund themselves. My film Big Gold Dream was given a small amount of funding by Creative Scotland. This funding was not given, I believe because I went to them with an idea extolling the virtues of Scottish Post-Punk and handed a blank cheque. We had to shoot, edit and make the entire film ourselves, promote it ourselves and negotiate a request to the Edinburgh International Film Festival to screen it there. It was only when it won that festival’s audience award – and a timely intervention by the film critic Mark Cousins – that Creative Scotland saw there was enough of a level of public interest to justify offering a small amount of funding towards its cost. The reality is that a rapturous section of the public have always advocated the importance of this music and without them we would never have been able to make Big Gold Dream. As the labels from this period discovered there was a ready audience ignored by the mainstream.

England’s cultural institutions and councils have not always offered a mainstream acceptance of Punk and its descendants. In fact, traditionally pop music has always had a very low ranking in the art world. If Liverpool Council would knock down The Cavern, the birthplace of the most famous pop group of all time, then what chance would anywhere else have? Manchester’s legendary Haçienda nightclub, owned by Factory Records, was demolished in the early 2000s to make way for private housing and Liverpool’s Cream nightclub was demolished as recently as 2016, the same year as ’40 Years of Punk’. How then did England reach a level of acceptance where the Heritage Fund website would proclaim ‘Punk London is supported by The Mayor of London’ (then Boris Johnston), or how did a gigantic Pete Shelley mural appear on the side of the building in his home town?

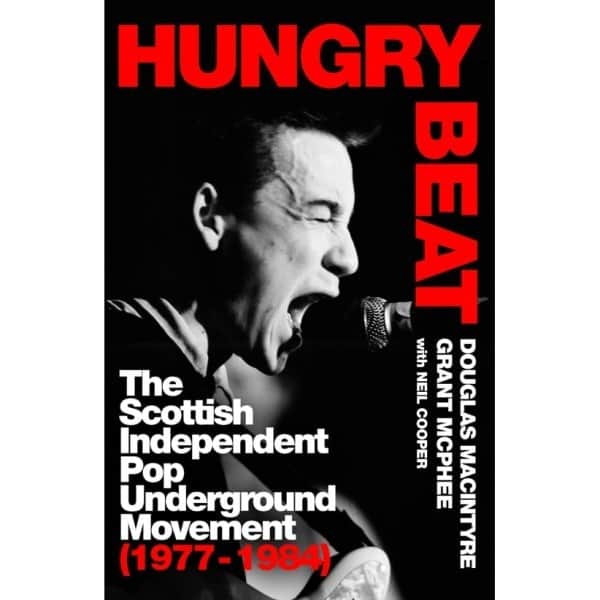

The answer seems to be campaign groups lobbying local councils and Government to honour their local heroes. It feels like much of the duty of winning over hearts and minds of disinterested councils and arts funding officials is to ironically, do it yourself. Hungry Beat is our attempt to focus on two maverick Scottish record labels, Edinburgh’s Fast Product and Glasgow’s Postcard Records, which helped spawn these dangerous ideas, and to explain in detail why those ideas are important and why they indeed have a significant legacy. Myself, Douglas Macintyre and Neil Cooper have spent the last two years working on this. It was funded by Hachette Livre, the gigantic French book publisher and released on the White Rabbit imprint, based in England and we hope it will be a small step towards changing the perception and value of independent music within Scotland’s arts

The ideology behind these record labels is still important and relevant today. 1979, the year Fast Product released its first Scottish single, was a moment when working class kids from Scotland were offered a very different future to what tradition had set out for them. It was a future which they could be part of and it showed that with some encouragement and inspiration they too could make something of cultural worth, on their own terms. Postcard Records would take this a step further a year later with the emergence of Orange Juice. For the first time Glasgow’s youth had their city portrayed in the music press, not just positively (which in itself is unusual) but being described as ‘cool’. I’d argue that Postcard’s Glasgow was as important as the 1988 City of Culture in representing Glasgow as a revitalised city. An independent record label made this happen.

Hungry Beat co-writer, Neil Cooper’s 2016 Herald piece on 90s DIY Flux Festival made the point that it took nearly 20 years for EIF to catch up and essentially do the same thing within the mainstream. While it’s fantastic that independent bands such as Mogwai can now enter the mainstream, the mainstream should have been supporting them at their inception, and not have a DIY event do the hard work.

A recent documentary on Manchester’s music scene included an anecdote describing the new-found pride sensed by the youth the day after The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays appeared on Top of the Pops. “The next day, everyone I knew was strutting about as if pride had been restored”. Listening to the youth and cultural institutions understanding those feelings is what will create change. Pride changes people and allows great things to happen. Glasgow City Council should be proud of their music, Edinburgh City Council should be proud of their music, The Culture Secretary should be proud of this music, Creative Scotland should be proud of this music. And they should show that they are proud and do far more to propagate the ideas and sounds their country gave to the world. Arts funding should be more than creating jobs for arts funders, it should be creating a legacy and allowing artists their own freedom and control because that’s where all great arts comes from. They should be doing things for themselves, understanding the value of something without the public having to bring its value to their attention.

*

On Saturday the 19th, at 7pm there will be a special Hungry Beat event at La Belle Angele: An evening of subtle dislocation featuring interviews / readings / and a live performance by The Hungry Beat Group (featuring members of Aztec Camera, The Bluebells, Article 58, Josef K/Orange Juice). Tam Dean Burn, vocalist with original Edinburgh punks The Dirty Reds will give a reading from the book. To get the evening underway, Bob Last (Fast Product and pop:aural) will be in conversation discussing the Fast releases.’

Ho hum. As usual Glasburgh, (or Edingow if you prefer), gets top billing and anyone else in Scotland is strictly second division.

There was plenty going on in Aberdeen, Dundee and Fife I know of, and I am 100% sure, elsewhere outside the M8 axis.

That’s ‘Scotland’ for you.

Just so.

I think you could say much the same for cyberpunk, whose origins predate the UK heyday of Punk around 1976 to 1978, and was influenced by its culture.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyberpunk

At its most intelligent, say in the novels of William Gibson, cyberpunk offers a coherent view of the near future (drawing on Japanese zaibatsu, bedroom coders and Scottish quantities of rain), although it is also used as a paint-thin aesthetic in other products.

Sure, I get the argument of this article, public arts funding is mediated by a beneficiary class of administrator-gatekeepers, is a form of patronage that leads to patronisation and packaging, and has a dampening effect on rage and revelations. Corporate artforms include (fictitious) evil corporations as a form of protective colouring. I guess the Revolution will be over before it can be televised, but parts of it might be live-streamed.

Culture can be created in the open-source worlds of global idea communism, wherein there is often an option to maintain moral rights of authorship, but not exclusive monetisation rights. Possibly many modern professional musicians have been reluctant to give up copyright, though (I am no expert) it seems to me music is a particularly derivative artform (we stole it from the birds, after all).

‘…public arts funding is mediated by a beneficiary class of administrator-gatekeepers, is a form of patronage that leads to patronisation and packaging, and has a dampening effect on rage and revelations.’

It’s more insidious than that. Our dependency on public funding leads to the bureaucratisation of art as ‘the arts’, the multiplication administrators within its institution and the concentration of power in those administrators, usually resulting in the extension of a degree of bureaucratic regimentation into our practice and standardisation into our products. Our dependency on public funding leads to the organisation of our productive relations into a ‘culture industry’, if you will, in the service of the national interest.

The very fact that we classify Scottish post punk as ‘Scottish post punk’ and cyberpunk as ‘cyberpunk’ is a sign of such bureaucratisation.

People don’t talk about English postpunk much do they? It’s just post-punk and that includes Scottish and stuff from anywhere in the world really. You do get some regional recognition of individual cities, as Grant suggests. Tbh though the placing of ‘Scottish’ in front of things is so normalised we barely notice it now. It is striking when you cross the border from the south how the word Scottish is everywhere, whereas south of it, ‘English’ or even British is not. The unequal power relations make this inevitable really, even desirable sometimes, but it can seem quite parochial. The question would be is there something distinctively Scottish about post-punk in Scotland? I struggle to say there is. Peel played it all back in the day and there was no obvious nationalistic element to the music – it was all post punk from this island (and NI) and adhered broadly to a set of tenets regardless of nation. I fact that was one of its unifying strengths – Stiff Little Fingers came from Belfast and the Troubles seeped into their music but even then, they were primarily a post-punk band, not a NI one: post-punk offered a way away from all that.

I would like to see Grant’s film.

https://youtu.be/8M5aOKj3UQI

@Niemand, I think you are missing the point about how people who think they are the centre of the universe name things. A bit like how the USA doesn’t use the .us domain name; it doesn’t mean a lack of patriotic fervour/jingoism. It’s just “the Football Association” down south, the SFA is the counterpart here.

Anyway, there are major organisations with British in their titles, others with ‘National’ or ‘Imperial’, but (because the British Empire remains a hereditary theocracy) there are many more names starting with ‘Royal’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_organisations_in_the_United_Kingdom_with_a_royal_charter

They have RSPCA, we have SSPCA.

Rather than being ‘parochial’, these names have to translate from Scottish streets to the world wide web and beyond. It is respectful and accurate to name things ‘Scottish’ that pertain to Scotland. It is a limitation of claim, an anti-imperial, anti-royalist statement.

Precisely, SD. Why do we feel the need to call our football association the ‘Scottish’ FA, unlike our counterparts down south, who are quite content to call the English Football Association (to give it its legal title) simply ‘the FA’? Doesn’t it signal a comparative lack of self-confidence on our part, just a person’s insistence that we address them by their ‘proper’ title signals a similar weakness of character on their part?

@Lord Parakeet the Cacophonist, mair blathers, a typical lack of humility, and a failure to understand that the concept of domain names is necessarily mainstream in our global information world. But anyway, my uncle, reeling from the disappointment of Scotland Men’s National Team campaign in Argentina 1978, was fond of saying “All the way for SFA”, so adding the national signifier to abbreviation has additional and unplanned value. Feel free to forsake this site for bella.org anytime.

I take the point SD and you are right for some things, but don’t think it the whole story. You focus on big institutions but what about stuff that this really does not apply to? I was thinking more of just your average shop or product. And post-punk – as I said post-punk is not ‘English’ or Scottish. It is a genre, a movement, and could just as easily have meant The Scars or Joseph K as Gang of Four or The Mekons (both first released on Fast incidentally), or Devo or Talking Heads. I dislike turning it into some kind of national thing because really, it was not – this is revisionism. Not that I am saying Grant is doing this – he just wants the Scottish *scene* to be recognised like it is elsewhere.

What is always odd about this is that this music was not directly beholden to the establishment and was often anti, but now we want it recognised by the establishment. Though it does not really compute it would be more apt if the DIY ethic could be applied to such a recognition. But the time of a mass of young people to do that is long gone – the youth of today understandably don’t care about the music of their parents’ youth.

But there is a different story too: though post-punk was not funded by the establishment at all, it did often coalesce due to people meeting at art schools, FE colleges, universities and polys which were free (fees and maintenance), funded by the state, allowing time and space for it. And such places provided income as venues (so even bands like The Fall who set themselves against the student thing, benefitted from it, and them). This all happened organically (better than being on the dole) and was not by design. Some of this is still retained in Scotland but only a fraction really. And the message of those institutions, including government, is different – it isn’t a place to explore so much as one to get you on the career ladder. There is much more fear and the institutions instil it – you must know / do this or you will be left behind. ‘Employability’ is more important than learning.

It is this breathing space and freedom to explore that we have removed from society and ‘the arts’ are now something you have almost to apply to do if you don’t want to starve. Either that or you actively do stuff you know stands the best chance of shifting the most units. It is all the wrong way round. Applying for funding comes with massive strings, control, accountability and increasingly, areas that they just won’t touch. It kills creativity and it allows only what it sanctions.

Yep, I agree; domain names (like ‘Scottish’ and ‘post punk’ etc.) are necessary to the identification of realms of administrative autonomy, authority, or control in relation to the information from which we construct our cognitive, evaluative, and practical worlds. Domain names are ‘just’ (‘no more than’) this.

But the question remains as to why ‘we feel the need to call our football association the ‘Scottish’ FA, unlike our counterparts down south, who are quite content to call the English Football Association (to give it its legal title) simply “the FA”.’

Do we construct our world thus from a perceived dominance of English or Anglocentric British culture? From a perception that the [English] FA is the given of which all other football associations are (to our minds) derivatives or ‘colonies’?

I suspect all those epithets (‘Scottish’, ‘post-punk’, etc.) serve to classify consumer preferences and/or self-identify ourselves into ‘tribes’. It’s all just music.

Rather glib. Of course it is all music but ‘just’? You could put that word in front of anything. It is just life.

Post-punk was not originally a marketing category (though of course became that too later) but a development of punk. It was primarily a musical movement that developed from punk but threw off its dogma without returning to the prog indulgences that punk reacted against whilst still being influenced by both punk and prog. It has a tribal element yes, but again, so does everything.

But it is *just* an adjective that qualifies a noun (e.g. ‘music’), which, as SD says, serves to establish a domain or ‘realm’ within the extension of that noun. Like a kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species, or individual, post-punk isn’t a given ‘thing’; it’s a conventional classification, a taxonomic ranking, a domain, in a system of data-administration.

Everything is ‘really’ *just* life and (in the case of music, for example – and, indeed, in the case of our world-making taxonomies themselves) *just* an expression of life. *Just* will and representation, as Schopenhauer had it.

Post-punk is a musical genre. It is a set of actual musical (and other) characteristics that developed organically. It wasn’t called post-punk initially. What it is called is not very important. Some called it new wave. What matters is what it indicates musically, which is a real phenomenon with identifiable aspects that give it meaning. There is no need for the word ‘just’. It is post-punk music.

(The (English) FA – was the first. Why would they name it after a country when no other country had one?)

@Niemand, sure, that’s clustering, and the name of the formal methodology for identifying them is cluster analysis. And we do this informally, as when Macbeth says:

“Ay, in the catalogue ye go for men;

As hounds and greyhounds, mongrels, spaniels, curs,

Shoughs, water-rugs and demi-wolves, are clept

All by the name of dogs”

In the case of dogs, we also go by ancestry, where there is a wolf-dog fuzzy zone. But if we didn’t have words like ‘dog’, we wouldn’t be able to communicate very well. There would be a lot of pointing and scribbling, and possibly animal noise impressions (and tedious postmodernist waffle). Terms like ‘post-punk’ live and die in their usefulness.

The British Broadcasting Corporation was the world’s first national broadcaster, and it wasn’t simply called the BC. Its predecessor was the British Broadcasting Company. The FA apparently had a short-lived rival, the British Football Association, which diverged on issue of professionalism, so that name was taken. But why, in today’s globalised world, does the name FA stick (in Crest and domain name)? Maybe it is because it governs the “Crown Dependencies of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man” as well as England, so EFA would be objectionable? Why is some tiny sporting contest between USA and Canada of no interest to the rest of the world clept by the name of The World Series? Why *do* USAmerican state bodies, corporations, NGOs, individuals object to using the .us domain name? What’s in a name?

Okay, post punk is ‘just’ (‘nothing more than’) [a genre of] music.

Except it is not just a genre of music. No genres of music are just that (it is an attitude, a dress sense etc though these are secondary signifiers). Nothing made by humans is just one thing. In fact very little can be thought of as just one thing. Even inanimate objects can be re-purposed and are all the time in fact.

I agree about the World Series SD – compared to the title BBC it seems absurd since at least the latter is a body that broadcasts to Britain (though really it should be the UKBC as it includes, officially, NI). You are right in a way, the FA does sort of see itself as ‘the’ FA now, though it can’t really have thought that early on. The England cricket team includes Wales of course as well (they have had several great Welsh players down the years)! The board, EWCB, is the English and Welsh one so is inclusive in that respect at least. I would say though that those that start something, get it going and then it becomes massive, worldwide even, do naturally feel a lingering sense of ownership; I am sceptical of seeing *everything* with England or Britain attached to it, through the Imperialist prism as it is a rather narrow, blinkered even, view.

Yep, you’re right, Niemand. It’s what I’d call ‘a form of life’ or ‘culture’. But ‘just’ that!

A really interesting read. I confess my ignorance to many of the bands and much of the music referred to, (was busy havin weans and getting a cafe goin at the time) but have real empathy with all you say. Scotland is teeming with artistic and creative talent but we lack a cohesive appreciation because we are disconnected and often ignorant of life in our own backyard. We somehow manage to acknowledge the diversity of the many cultures of Scotland, we just don’t experience or share in them enough, if ever. This is the Nation’s wealth but we don’t see fit to share it or celebrate it; and worse, we do sometimes make an investment in it and don’t tell anyone.

Grant says

“Creative Scotland should be proud of this music. And they should show that they are proud and do far more to propagate the ideas and sounds their country gave to the world. Arts funding should be more than creating jobs for arts funders, it should be creating a legacy and allowing artists their own freedom and control because that’s where all great arts comes from. ” Hear, hear!!

I believe Creative Scotland did fund the documentary by which Grant sought ‘to propagate the ideas and sounds their country gave to the world’.

@Jean Urquhart, a lot of video games are crowdfunded these days, perhaps a model that could be applied more widely:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_video_game_crowdfunding_projects

Yep, supporting an artist’s work through entering into voluntary association with that artist (‘crowdfunding’), rather than through either state/private patronage or the commodification of that work, is a good way to keep it independent.

‘Crowdfunding’ is just newspeak for what used to be called ‘voluntary subscription’., which remains the life-support of the independent journalism of Mike and others.

Really a Glaswegian version of Tony Wilson Place is somewhere near the bottom of my personal list of things Glasgow needs, or even, tops the list of stuff it doesn’t need. Can we get any further from a “Worker’s City” vibe than this I wonder. Yes the city’s being hollowed out by neoliberalism (but now under a New Improved[tm] SNP council); yet we can have more Brave, Stunning gentrification based around the (very-)recuperated legacy of punk. As for the under-celebration of “Sub Pop” acts, growing up in Glasgow all I remember was people raving to Jeff Mills while the local mainstream media (List et al) and promoters were ramming this ironically twee (but maybe not ironic enough) guitar music down our throats. I mean some of it was OK, but a lot of it was tres middle class in the pejorative sense.

One thing Grant does not discuss here is that Postcard and Fast were really rather different. Fast was much rawer, post-punk proper. Postcard was the later twee stuff and arguably at the heart of the ‘new pop’, a reaction against the ‘miserable’ post-punk.

Here’s some Fife stuff, for anyone interested.

http://www.kirkcaldybands.com/index.html

Good gig last night.