Work as if you were in the Early Days of a Creative Republic

Over the coming weeks over the holiday period we’ve commissioned a series of writers and activists to reflect on where we are and review not just the year but the time we find ourselves in. This is the second of a series reflecting on the State We’re In.

In 2022 I spent a fair amount of time talking to friends, family, and colleagues of Alasdair Gray about his life and practice.

It was a rare privilege to sit in the Alasdair Gray Archive over many days, surrounded by objects accumulated over a lifetime: donated furniture, annotated books, decorated trinkets. For a man who gave away most of what he ever had, this is a particular kind of legacy: assembled from the objects that you carry with you, half-forgotten, for their familiarity; that happen to bear your fingerprints.

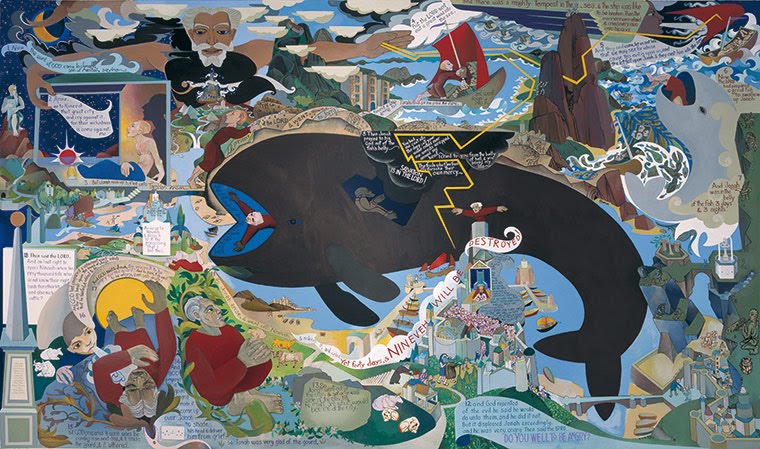

Maybe we all carry the drive to make objects that outlast us, but to spend time with Gray’s legacy is to experience this need to make ‘good and beautiful things’ as an elemental force. One imagined world fills the eye only to reveal another and another: knotted threads cannot be untangled, ideas spill over across space and form and somehow coherent things emerge from the chaos, whole.

One of the curious things about Gray is that — despite being a long-term advocate of Scottish independence and the author a popular book on the subject — he never really had that much to say about it. I don’t think it particularly interested him as a debate, it was just a series of self-evident truths that could be set alongside bigger, cosmic, causes. The key word here is perspective: as a dogged republican, politics for Gray begins with as much power as close to home as possible, the other layers should be shaped based on how much humanity can be injected into them at each stage.

There’s a well-known argument, articulated by the critic Cairns Craig, that Scotland ‘declared cultural devolution’ through the work produced by figures such as Gray, in a way that prefigured devolution itself. In 1979 representative politics had stalled but writers, artists, musicians, journalists and thinkers stepped into the void and resolved to write a country into being. This narrative is poignant enough to be literally carved into the walls of the Scottish Parliament; but all that marble and granite containing snatches of verse along the Canongate is a little too polished.

The reality was a gritty set of material circumstances that brought a Parliament and a revived culture into being. This was the brief British social democratic experiment, the radical expansion of access to education, to publicly funded art, to great new social and economic freedoms. Gray, despite being the most idiosyncratic of all contemporary Scotland’s cultural forefathers, was explicit about this: he was a child of the post-war settlement, nurtured in the autodidact traditions of the interwar labour movement, and the old municipal socialism of the Glasgow Corporation; raised by parents who had witnessed the abject want of the depression years.

A different set of circumstances could easily have seen Gray stick with the day job: as an art teacher who turned up late for his own classes. Instead, half a square mile of Glasgow’s West End became a cockpit for a boundless imaginative genius. Fortunately, the bourgeois-bohemian world of Glasgow’s West End was then fed by all the opportunities for work and patronage that the combination of three big public institutions (the hospital, the BBC and the university) could provide.

That very particular place at that very particular time was a secure enough setting to allow Gray’s mind to productively meander for years. So much of the vision of Scotland that resulted, where reality is in constant tremor between utopia and dystopia, we owe to one sprawling council house on Kersland Street (that the artist would sublet in order to subsidise his own labours).

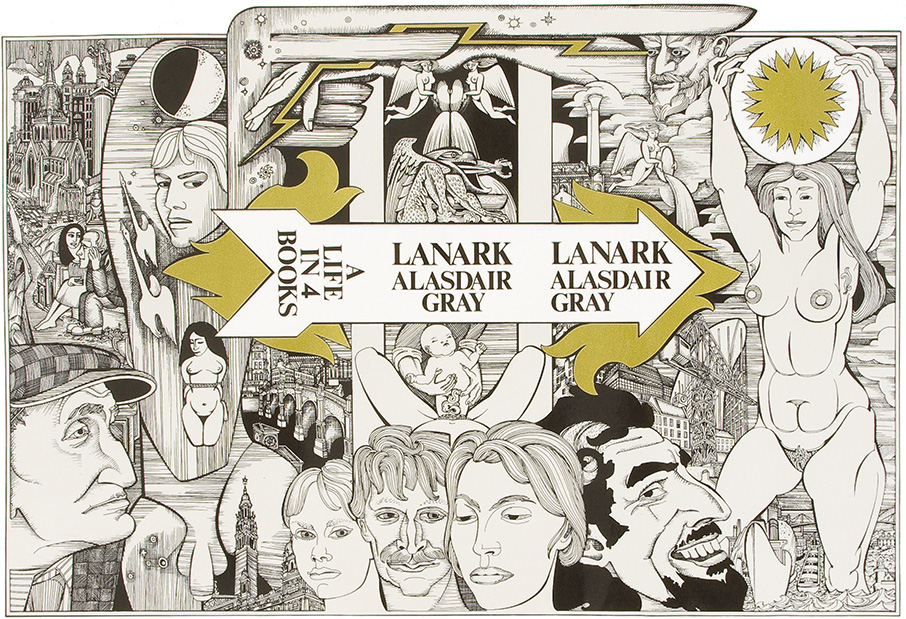

This indirect public subsidy, probably provided by a benevolent housing officer at the council, saw the publication of Lanark, 1982 Janine, Five Letters from an Eastern Empire, and many other good and beautiful things.

Scotland in 2022 still wants those kind of remarkable creative outcomes, but without providing the inputs. In commodifying its higher education system, its cities and so much besides; this is what we lose. There will always be someone behind a Tesco counter with grand universalising perspectives on Scotland and the cosmos that we will never know: because she can’t go on the dole for fear of death, because she spends two-thirds of her income on heating and rent, because these freedoms are now presented as luxuries that we are told we can no longer afford.

You can walk along Byres Road today and see money enough – embodied in the queues of SUVs, in the thousand pound a month tenement flats that now lure rent refugees from London liberated after the pandemic. All of those returns to capital still owe a debt that they will never repay to a generation of working class people who gave everything to make Glasgow a place of the imagination once again; a place with enviable hordes of cultural capital.

This is at the root of the strangeness within the nation in 2022, a nation that seems closer to having a state to call its own than it has ever been. What for? In the two decades since devolution, the global economy has delivered many miraculous things, but it has also made everywhere seem that bit more like everywhere else. It is all a bit too polished and neat: the dirty work of making material conditions that can create truly egalitarian spaces is historicised by Holyrood, frozen into the stonework. We have been set free with just enough of a nation to be autonomous in a global market, but no more than that.

Proceedings over recent days have reminded us that the Parliament’s most basic promise – to be a resilient place for Scottish public debate in an era where so many other civic institutions are either collapsing or being repurposed for private ends – has severe limitations. 2022 comes to an end with a 10 per cent cut to Creative Scotland’s budget, and iconic cultural venues shuttering. Creative Scotland’s funding has been static for so long that many cultural producers live in a kind of limbo; committed to Scotland but scarcely able to make a living here.

All work that involves public, civic or creative missions is always subsidised by somebody. The loss of faith in publicly funded culture is transforming Scotland, like the rest of the UK, into a place where only the children of the rich can steer the public imagination, shape public discourse in the media, and make things simply for their own sake.

Conditions of mere survival cannot sustain a society for long. For example, great public spectacles and cultural moments proclaim so much more than their content: they make us understand our place in the wider scheme of things, catch glimpses of truths often hidden, even call countries into being.

In 2022 I witnessed this power in chilling, medieval mode, when the sovereign body came to be paraded in Edinburgh and thousands watched in reverential silence. For the first time since 2014, I understood something of what it must have been like to be a No voter as the Yes campaign took to the streets: I saw a mass of people respond to regal sovereignty, where once, not so long ago, there had been a sovereign people.

Today, another source of power is out there on picket lines defending the last ragged remnants of the social safety net that gave us Gray and so much else besides. He was fond of observing that there were only three real jobs: a teacher who cures ignorance, a doctor who cures disease and a socialist who cures poverty. In the poem ‘Not Striving’ Gray talks of finding ‘the room I wanted/It was a gift, like life.’ Much of the artist’s vision was about glorifying all the hidden labours, the social reproduction, that all art owes a debt to.

If 2023 is to bring us closer to the Scottish Republic that I still plan to end my days in, it must bring the victory of the nurses, posties, rail workers, paramedics, teachers: the life-sustaining workers who sit behind all the good and beautiful things that are yet to be made.

This article reminded me of the second episode of Art that Made Us, which looks at how revolutionary ideas and reactionary responses flowered in the aftermath of medieval plague (before apparently being somewhat tamed by increased prosperity and longer-term thinking):

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p0bvgvt3/art-that-made-us-series-1-2-revolution-of-the-dead

The contrast with today, possibly, is that longer-term thinking is more intractably opposed to the business-as-growth model. But the propaganda art of Richard II looks as ridulously over-the-top as royal propaganda today. In one sense, I dispute a statement in the programme that satire is a weapon of the weak (of the oppressed, yes), as the immense cost of pro-royalist propaganda is far more demonstrative of weakness. How vile must you be to need such vast expenditure on public relations? How evil must you be to lean so on God and Church? How many skeletons in your cupboard must you have if you rely on the world’s most draconian secrecy regime?

I’d go along with much of this. But surely the big public spectacle is hollow when the people dont really connect with what is being commemorated. We need the structures for the spectacle to have meaning.

Christopher Silver refers to Alasdair Gray’s house in the West End of Glasgow; specifically ‘one sprawling council house on Kersland Street (that the artist would subset to subsidize his own labours.)’

He further suggests that this was ‘probably provided by a benevolent housing officer at the council’

At that time, Glasgow had probably the most acute housing needs in Western Europe. Getting a decent house from the Corporation was a dream/nightmare for tens of thousands of people. It was said that the best way to be remembered after you died in Glasgow was to put your name on the housing waiting list.

There were constant rumours of bribes being paid to housing officers and of preferential treatment being given to the well connected; particularly, those in the Labour Party. Sub-letting houses was banned. For most people, over-crowding was such that the idea of doing so was totally fanciful.