Remembering Working Class Scottish Voices and Histories

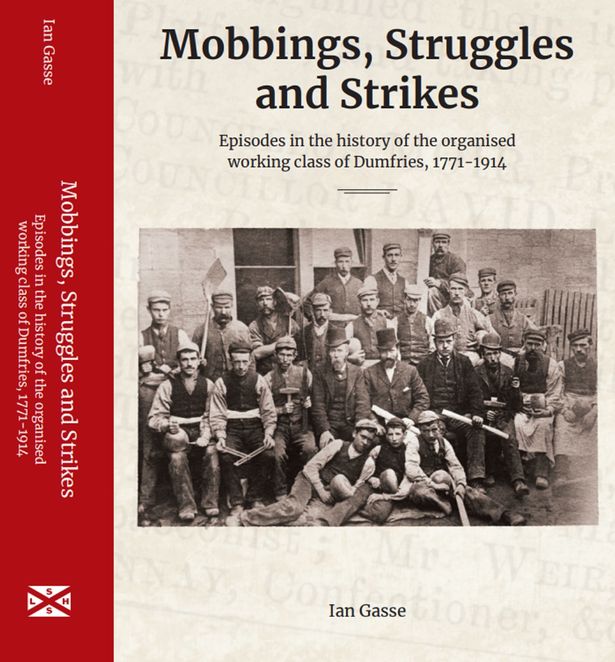

Mobbings, Struggles and Strikes: Episodes in the history of the organised working class of Dumfries, 1771-1914, by Ian Gasse, Scottish Labour History Society, £22.00. Review by Katharine McCrossan.

As the number of those participating in or impacted by strikes continues to increase amidst the ongoing cost of living crisis, it is unlikely that the issue of industrial unrest will lose relevance any time soon. Given such context, the timing of Ian Gasse’s recent publication Mobbings, Struggles and Strikes: Episodes in the history of the organised working class of Dumfries, 1771-1914 could scarcely be more apposite. Although individuals could very well regard such proceedings with a degree of familiarity, considering the proximity of current events and legacies of troubled labour relations within Scotland, there are still swathes of our collective understanding of the subject which remain underdeveloped. In this latest offering, the author seeks to develop our historical awareness of the various struggles of the organised working class of Dumfries and Maxwelltown between the late eighteenth and early twentieth century.

From the outset, Gasse explains that this volume should be viewed as a companion piece to his 2021 work Something to Build On: The Co-operative Movement in Dumfries, 1847-1914. Similar to this earlier work, the author views the research contained within Mobbings, Struggles and Strikes as an act of historical recovery – that is, an attempt to ‘reclaim’ elements of history that have been (for whatever reason) forgotten.

Gasse explains that the two publications, taken together, represent a comparatively ‘finished’ body of work on working-class responses to the development of the capitalist economy in Dumfries in the nineteenth century, or, at the very least, provides a solid foundation upon which further historical research can rest. In fact, Gasse has already outlined several potential new routes of further research, including into railway and shopworkers trade union activities, actions of factory workers in Nithsdale, Troqueer and Rosefield Mills, and individual figures such as Samuel McGowan, Andrew Wardrop, and David McGill.

In light of the additional avenues of enquiry identified, Gasse describes the collection of articles contained within the volume as somewhat ‘arbitrary’ and ‘necessarily incomplete’ – the latter due to obvious constraints of scale and space and the former because of the often-sporadic availability of primary sources.

While there is no denying the validity of this explanation, it would have been beneficial for the rationale behind the inclusion of topics selected for examination to have been explained more clearly. This is especially true regarding the subject of women’s suffrage. Given the subject matter and time frame under consideration, one would have expected this issue to have merited more attention than it has ultimately received, included only as an appendix (with the potential appearance, therefore, as an afterthought) to one of the main articles.

In a slightly unconventional format for a single-authored text, Gasse has intended for each of the seven articles contained within this work to appear as ‘stand-alone’ pieces, though in doing so acknowledges that this approach tends to generate an element of unavoidable repetition in the provision of information about Dumfries and the surrounding area and the development of trade unionism in the nineteenth century.

Despite this, Gasse frames any potential reoccurrence as an opportunity for the reader to ‘fix’ certain historical details within their mind. In another somewhat unusual decision, Gasse has chosen to present the primary material used to inform his research in the form of (often lengthy) extracts in the text in order to allow ‘the voices of the times to “speak” directly’ to the reader. While there is obvious merit in this approach, the frequency with which such interjections appear in the text may prove distracting for some readers.

In a largely chronological approach, the author first offers an examination of various food riots between 1771-1842, noting that such events represented an early example of collective action by the town’s working-class inhabitants in the face of exploitation and exclusion from the political process. A distinction is also drawn between earlier instances of food riots (between 1771-1817) and the later riots of 1826 and 1842, which Gasse suggests were less concerned with securing basic food supplies and more of an exhibition of collective anger demonstrated by those without recourse. In the next (equally weighty) chapter, attention then turns to local participation in national campaigns designed to secure working class men the right to vote.

Sustained interest in the aims of the Chartist Movement between 1838-1849 in Dumfries and the surrounding areas evolved into conspicuous support by 1867, by way of rally and demonstration, for parliamentary reform. Although the efforts of the wider national campaign resulted in the introduction later that year of the Second Reform Act in England and Wales and the Representation of the People Act (Scotland) in 1868, it would be 1884 before the passing of the Third Reform Act granted some working-class men in county constituencies the vote.

Moving on, Gasse then documents the efforts made by local farmworkers to establish protection societies or ‘ploughmen’s associations’ during the 1860s in an attempt to secure better conditions and negotiate a higher rate of pay, and the subsequent resentment such workers faced from farmers hostile to such rudimentary ‘trade union’ action. The remaining articles focus on four separate strike episodes within the local area, including those conducted by bakers in 1889 and 1905, stonemasons in 1899, and hosiery factory workers in 1912.

In presenting such a richly detailed and meticulously researched series of articles, Gasse provides excellent insight on the activities of the organised working class in Dumfries between the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries, while also contributing to our understanding of the development of the trade union movement in Scotland more generally. Through this volume, Gasse ably demonstrates the value of examining industrial unrest through a local lens, and also in focusing on an area not famed for its radical reputation or activity within the labour movement. Gasse is able to illustrate that the inhabitants of Dumfries and the surrounding areas were not only aware of ongoing issues related to the wider labour movement, but that they were prepared to participate and secure its aims. In doing so, he has ensured that such important struggles will not be forgotten.

That history would be concurrent with the Dumfries fur market mentioned by Roger Lovegrove in Silent Fields: the long decline of a nation’s wildlife. While Lovegrove attributes much of the responsibility for British wildlife carnage to royalty, ‘aristocratic’ landowners and privileged game ‘sportsmen’, the author also covers some working-class cruelties towards animals especially in industrialised urban areas, but also in rural or semi-rural settings. If women’s suffrage only appears in an appendix, I suspect animal rights don’t get a look-in. Still, people presumably drew comparisons between human workers and the working animals they extracted labour from. Presumably it would also have been an additional animal welfare issue if while human workers went on strike, the animals they worked beside were being oppressed by untrained scab labour.