On Canada’s attempt to stem its unrelenting drugs epidemic

Jamie Maxwell explores North America’s unrelenting drugs epidemic – and Canada attempts at a opioids trial.

On 31 January, British Columbia launched a limited experiment in the licensing of hard drugs. For the next three years, anyone in the province aged 18 or over will be allowed to carry a small amount of opioids, including heroin and fentanyl, for personal use. The experiment was launched with the approval of Canada’s federal authorities. On 30 January, Carolyn Bennett, one of two health ministers in Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government, said the pilot signalled a “monumental shift” in the country’s drugs policy away from stigma and prohibition and towards support and rehabilitation.

BC is an obvious staging ground for this trial. The statistics tell their own story. Last year, the province, with a population of just over 5 million, registered more than 2,200 overdose deaths. Meanwhile, Scotland, with a population of 5.4 million, registered half that number. In other words, BC’s drugs crisis is twice as bad as ours – and we have the worst drugs death rate in Europe. But the scale of the problem has to be seen to be believed. I lived in Vancouver for two years between 2017 and 2019 and rented a flat in the east end of the city. When I took the bus into town from my neighbourhood, the route would pass through Downtown Eastside.

Downtown Eastside is bleak. Its streets are packed with people shooting up, nodding out, or otherwise being intravenously revived with Naloxone. There are police and paramedics everywhere. It is a dozen or so blocks of municipally-concentrated squalor. And yet, the area benefits from a small army of activists, many of them ex-addicts, striving to make things better. One dreich January morning, I visited Insite, North America’s first official safe injection site. The project has treated millions of people since it first opened in 2003, on the basis of a rolling annual exemption from Canada’s drug laws. From a distance, I watched as users overdosed, and were resuscitated, in the glass-panelled shooting booths.

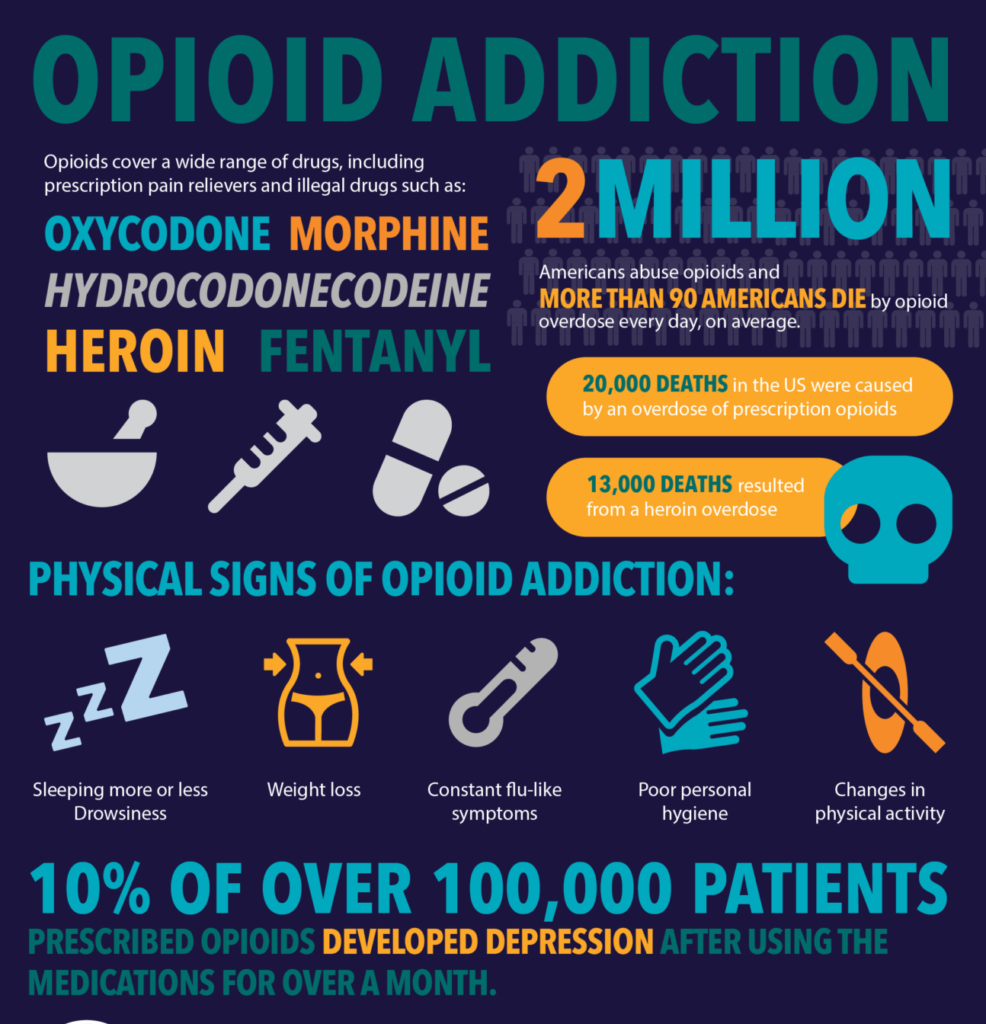

However, Insite has struggled in the face of North America’s unrelenting fentanyl epidemic. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin. According to The Lancet, the drug has killed 600,000 people in Canada and the US since it first arrived there in the 1990s. Without radical intervention, it could kill the same number again by the end of this decade. There had never been a fatal overdose at Insite when I visited in 2019. The sense of fear among the project’s volunteers was nonetheless palpable.

In 2016, in a bid to staunch the fentanyl death wave, BC’s provincial government declared a public health emergency. In 2018, the BC Coroner’s Office revealed that 52 per cent of overdose victims displayed “clinical or anecdotal evidence” of mental ill health prior to their deaths. Canada’s fentanyl crisis is further complicated by the country’s knotted racial dynamics. According to Dr Nel Wieman, BC’s acting chief medical officer, toxic drugs are killing Indigenous Canadians at five times the rate of white Canadians. Around 30 per cent of people who live in Downtown Eastside, itself the product of compound policy failures and long-term ghettoized neglect, are Indigenous.

The link between poverty, mental illness, and addiction isn’t exactly new. But that hasn’t stopped the right from responding to BC’s partial experiment in decriminalization in the most hysterical terms possible. “The Trudeau-NDP approach is on open display in Vancouver,” Pierre Poilievre, the leader of Canada’s federal Conservative Party, said on 1 February. “It is a complete disaster, hell on earth.” (The NDP is the nominally centre-left party that runs BC’s devolved legislature.) The reaction from conservatives here in Britain has been just as unhinged. In a piece published on 27 January, a correspondent for the Daily Mail described the “jaw-dropping” experience of walking around Downtown Eastside. In addition to wrongly identifying Vancouver’s North Shore mountains as “the Rockies”– the Canadian Rockies start 500 miles east of the city, on the Albertan border – the writer blamed “ultra-progressive” wokeism for the “utterly mad decision” to treat, rather than truncheon, addicts in the area. “In its sheer radicalism”, the move to decriminalize is “without precedent anywhere in the world,” he intoned.

Yet that is precisely the issue: the BC pilot isn’t anywhere near radical enough. The new threshold for non-criminal opioid possession has been set at 2.5 grams, well below the 4.5-gram limit requested by the BC government and considerably less than many users carry with them on a day-to-day basis. Therefore, “those most impacted by the current criminalization will be least impacted” by the trial, Amber Streukens, a drugs activist in BC, said on 30 January. There are concerns, too, that suppliers in an increasingly lethal fentanyl market will simply adjust to the new threshold. That is, opioids will become more potent in smaller batches in order to meet the 2.5-gram cap. It’s almost as if addicts are being “set up for failure,” Kevin Yake, vice-president of VANDU, a Vancouver drugs advocacy group, remarked last year when plans for the pilot were first published.

Piecemeal changes to the law aren’t necessarily unwelcome, but they won’t address the root causes of the crisis. One of the reasons Downtown Eastside exists is that housing costs in Vancouver have spiralled out of control since the late 1990s, generating a steady stream of working-class panic and suburban displacement. Downtown Eastside is a standing testament to elite metropolitan indifference – a place where inequality, racism, and illness have been left to fester for decades without reply. The danger now is that the BC trial fails and overdose rates continue to rise, weakening the political case for more comprehensive reform. Indeed, prohibitionists are already teeing up their attack lines. The lesson for opponents of prohibition is clear: if you’re serious about eradicating the ‘stigma’ of addiction, nationalize the supply and regulate the product. Anything less isn’t going to cut it.

I lived in Van from 1997 on and of until 2016/ then in Victoria, the flat I stayed in out of the immediate group 3 or there friends died from fentanyl, it’s a shit show and I’ve seen it only get worse, there is little to no affordable public housing(an alien concept to many Canadians outside of east Van) many of the the rehab programs are underfunded, and they failed to implement a Portugal style program people have been taking about for years. I lived a block from Hastings, in Strathcona and on main and Fraser and near the drive, a lot of good things being done by a lot of good people in activism and the like but really, it’s been a long and sad journey of decline as the city has grown insanely wealth with property speculation. it’s looking worse and worse and I doubt this is going to do anything much, on top of that the number of police killings has go through the roof, with at least 40% native, unfortunately there isn’t much of a big PR machine around these issues, I very much doubt you’ll see indigenous lives matter protests spreading across the world. I used to do day labour so most guys you work with are indigenous or drug users, it’s a different life over there that’s for sure. Canada isn’t going to change anytime soon, it’s an active colony as they say. It’s a shame, when I was first there in 1997 I worked with Greenpeace and WCWC fighting against clearcutting back then it did feel like change was taking place now it feels more like the USA, it was never great for indigounes people but it’s worse now. but at least BC’s not Alberta.

what a sorry state to be in, addiction is a horrible curse on anyone, poverty and no job or little help. the problem with drugs is the quick fix and then your hooked and its all modesty gone, live like a cave man and do anything for a shot, wish the people suppling would have a look at what there greed is causing and if they keep that up I would have to vote for the death penalty for the guys that control the flow sad as that is but drastic times need addressed to save the world

“The lesson for opponents of prohibition is clear: if you’re serious about eradicating the ‘stigma’ of addiction, nationalize the supply and regulate the product. Anything less isn’t going to cut it.”

I found this very interesting. I can see how nationalised supply and regulated product works for less harmful and addictive drugs like cannabis, Canada being one example. Could you point me to any examples or models of how this may work with more problematic substances such as cocaine or opioids?