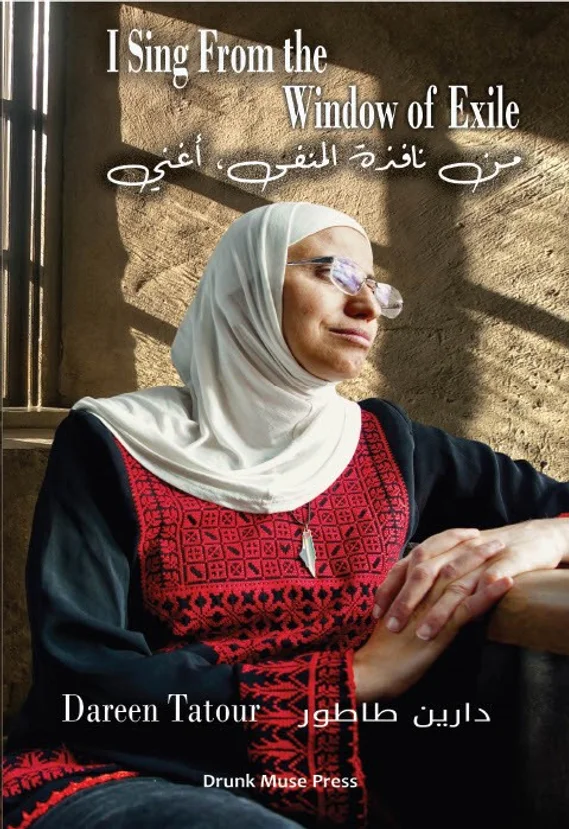

I Sing From the Window of Exile

A Review of Dareen Tatour’s collection of poems: ‘I Sing From the Window of Exile’, published by Drunk Muse Press, available from Drunk Muse

‘there’s no giving up.

Destroy my house,

demolish my lifetime,

burn my trees down …

I will remain in your faces …

No, and a thousand

a thousand times no

I won’t; I won’t; I won’t

emigrate.’

̶ from I Will Not Emigrate, by Dareen Tatour; the final and/or opening poem of ‘I Sing From the Window of Exile’.

In 2015, Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour was propelled into the worldwide media when she was first jailed by Israeli authorities for the ‘crime’ of having written and shared her poem Qawem ya sha’abi, qawemhum (Resist, My People, Resist Them). Her current collection of poems, the second of her works to be published by the Drunk Muse Press ̶ they also brought us her memoir: ‘My Threatening Poem’ – is her first collection of poems to be made available in English translation, alongside the original Arabic texts. It is a privilege to be able to read her poetry. It would have been so different had this extraordinary poet been silenced by the authorities who deemed her words such a threat. That Drunk Muse Press, one of Scotland’s most exciting new, independent publishers, have understood the need for us to hear this so nearly quashed voice is a gift. We are privileged also in that this is poetry that sings with lyrical musicality, and with rich imagery, inviting us to be alongside Dareen as she evokes, recovers, and persists with the resistant spirit of a captured bird: continuing to share her song, as when she once flew among the palms, radiant in the sun.

‘I Sing From the Window of Exile’ offers incisive and lyrical insight into the specific experiences of this Palestinian woman, whom an oppressive and authoritarian regime had hoped to subdue, who has been forced into exile from a homeland that was already, for her and her compatriots, a precarity to be clung to through the tenacity of resistance founded in a great love for place and people. It is a testament to Dareen’s ability to ‘speak the world’ (as poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant advised all poets must; see McCullagh, 2021), that these tremendously personal expressions also resonate with wider concerns generated by numerous contemporary crises; crucibles of the plosive shocks that are reverberating across the diverse regions of this planet.

Many of the poems in this collection speak directly of the destabilising impacts of migration, and refuge-seeking; of unbelonging; the disruptions of the meaning of place that denude cultures, environmental wisdoms, and the dignity of those displaced. In Home, a poem that is typical of so many in this publication in the clarity of its graceful imagism, Tatour encapsulates the displaced person’s loving and painful internalisation of the places (and people) that have formed them:

‘it’s carrying its tiny name

travelling through our dreams

and its dreaming in us.

We are its last letters’.

These exile ‘songs’ also share the poet’s experiences into a growing, global assembling of accounts concerning the silencing, and the criminalisation of women and girls carried out under the guise of legislation by abusive and discriminatory regimes. The theme is vibrant in Loss, a poem in which Dareen claims sisterhood with people and with place, both refuting the erasure of her homeland, and of herself as a woman; imprisoned, tortured, and exiled:

‘With the glances

of a woman called Palestine

I reassure myself

that I’m present and still exist’.

The Rites of Exile

The collection opens, at least for those reading (from left to right) in English, with a sequence of 14 short poems entitled ‘The Last Invasion’. Addressing the ‘rituals’ ̶ those experiences and affective states that an exile adopts as they become dislocated ̶ great care is taken by this poet, offering a series of brief, tenderly wrought poems to ease our access to the particularity of a Palestinian woman’s feelings, thoughts, and actions as journeys, physically and emotionally through the privations that lead to the window of her exile in Sweden, where while ‘quietness settles’, she must negotiate again her place in the world.

Both of these experiences – the need to become through new terms of belonging, and the necessary but agonising dynamics of letting go of origins ̶ are evoked keenly in two poems that make up part of ‘The Last Invasion’, the ‘opening sequence’ (for English readers) or, alternatively, a possible conclusion to the collection (for those reading in Arabic):

‘Here is where horror lies,

my being outside this city’s border,

deprived of my right to my land.

Challenge is my only opportunity to adore it so powerfully’

̶̶ from Entering the City

‘Like a baby leaving the womb

cutting the umbilical cord with its own teeth’

The visceral experience of choosing resistance and its consequences

‘I live on bits and pieces of dreams …

on a surface of an idea called the return’.

̶ from Farewell

Incarceration, compassion, and resistance

Throughout ‘I Sing From the Window of Exile’ Dareen Tatour engages her readers with the duality of enduring incarceration while proclaiming resistance, through the elegant and plaintive portrayal of recurring motif: a bird, caged yet still singing. In a middle sequence of the book, ‘The Tales of The Canary’, this singing travels us through poems concerning the extremes of the mistreatment she endured throughout both of the periods during which she jailed; when the indictment was first filed against her in 2015 and following her conviction in 2018:

‘The bird of my poetry sang praises and chanted ̶

joyfully the melody hovered and circled …

it destroyed the shackles,

visited the field and the grove …

in my prison ̶

I am the free one.’

̶̶ from I am the Free One.

Throughout, Dareen’s poetry returns to theme upon which this collection pivots; that it is our creative expression, which will sustain, and even save us:

‘ … I race

like a canary to take my shelter

in the next of a poem …’

̶ from Female Poet’s Detention.

These are deeply felt poems. They fill the pages of this book with Dareen Tatour’s generous vision that even in the circumstances of despair, our ability to understand, through expressing the essence of our experiences, connects with our openness to imagining more possible realities for ourselves, and for others. It shimmers in resonance with Susan Sontag’s encouragement that writers must pay ‘attention to the world … trying to understand, take in, connect with, what wickedness human beings are capable of; and not be corrupted—made cynical … —by this understanding …’. Readers of ‘I Sing From the Window of Exile’ can be in no doubt that Dareen Tatour’s attentive poetics reveal a consciousness far from being sublimated into cynicism:

‘I will keep on dreaming as long as I’m alive,

as much as I want,

this is how I live …’

̶ from I Will Not Die.

Here is a poet who gives us poetry that calls us to attentiveness also. Not at any point in this collection does she evade giving expression to the terrible consequences that arose when her ‘poetry [was] convicted’:

‘the lands of skies are confiscated …

no visitor but depression …

pitch black nights;

Fear, there, is dreary

and the echoes of agonies in its silence is absurd …’

̶ from Prison Portrayal.

The brutalities she endured in captivity, including verbal and sexual abuses; the indignities of naked searches and criminality of attempted rape, are connoted through the felt sensations evoked in a sequence entitled ‘Hallucinations’. Tatour rails against the injustice meted out by her imprisoners, and explores psychological states of distress, and disassociation it provokes. At times there is a wry tone, a gentle mocking of the ridiculous audacity of her imprisonment, but it is humour mediated through such suffering:

‘ … a lifeless picture

in a torn book …

I am the one who seduced the jailer

by my imprisonment and desire.’

̶ from An Innocent Hallucination

Dareen offers us a lyrical education in attention to the grammar and vocabulary of her homeland too. These are poems fragrant with palms and olives; bedecked with flowers, rippled with birdsong. Their degradation through oppressive force only intensifies Tatour’s (and our own) sensuous connections to them. In poetry she is creating mnemonics of place and family, of hope in exile:

‘the flower of life haunts me,

I water it with the fountain of struggle …

I stare at the birth of peace …’

̶ from ‘A Woman’s Scream’

It is an extraordinary feat to persist in assembling such enchantment while also giving witness to the inhumanity she observes and has been subjected to. This complexity of perception, of nuance, is also reflected in Dareen’s embrace of the entanglement of relations between Palestinians and Israelis, depicting them as a competition between side-by-side ‘siblings’.

Openness to the perspectives of others is the poet’s daily diet. It includes eliciting what might otherwise be ignored, or that to which people have become inured, transforming it into new highly noticeable idioms. As writers and as readers of such works we become trained in exercising ‘our ability to weep for those who are not us or ours’ (Sontag, 2007).

Dareen Tatour’s own poetics of weeping, her eloquence in the realms of compassion, calls us to meet the people of Palestine anew, as she did herself in prison: ‘the destiny of lovers’, whose crime has been adoration of their home in the world. We listen with her to the stories of these ‘children of stones’, finding in her words a poet and her people ‘born from the womb of pain’, and growing through injustice ‘like a flower in the soil of salt’.

Continuing to sing

We are, indeed, privileged to be able to access and read this collection of poems, ending and beginning (in English, and Arabic, respectively) with the ululating song of an exile who refuses to emigrate. Dareen Tatour, in ‘I Sing From the Window of Exile’, is ‘a palm tree standing high’ whom, while she must live an intimate distance from her belovéds ̶ unable to give ‘the kiss of Eid’ to her best friend, or enjoy ‘the aroma of Manaqeesh and the burnt Za’atar wafting’ from her mother’s oven ̶ remains, always close ‘shining like a sun, radiating warmth, resisting’.

‘I Sing From the Window of Exile’ by Dareen Tatour is published by Drunk Muse Press, and is available to buy from https://www.drunkmusepress.com/product-page/i-sing-from-the-window-of-exile