A’ Dùsgadh na Gaoithe / Waking the Wind; Finding the Folklore of a Fragile Ecology

The exhibition A Fragile Correspondence opened last weekend in Venice, one of the eight collateral events for the 18th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia at the Arsenale Docks, S. Pietro di Castello, Venice. Commissioned by the Scotland + Venice partnership and curated by the Architecture Fringe, -ism, and /other, A Fragile Correspondence responds to Biennale curator Lesley Lokko’s theme of The Laboratory of the Future by exploring the nuances connections between land, language and the climate emergency. Here we hear from Raghnaid Sandilands who was part of A Fragile Correspondence.

A Fragile Correspondence – Trailer from Scotland + Venice on Vimeo.

‘But we heard the song and we found the gold.’ Katherine Stewart

‘Language is an old growth forest of the mind.’ Wade Davis

The forest landscapes of Strathnairn, on the south side of Loch Ness, are a mix of conifer plantation, community owned native forest and old-growth birch forest. Higher, in the foothills of the Monadh Liath, there are fragments of ancient forest with root remnants of birch and Scots pine deep in the peat. The Gaelic names carry knowledge and resonance, named by those for whom the living world was more alive and in times when ecologies were far richer.

My exhibited piece is a stitched map on linen that traces the shapes of Doire Gheugach (branched grove). An ancient growth forest, out of sight and far from memory, its name long since excised from the maps but, there was another time when these forests were known and named…

Today overgrazing by deer means that any new growth is hindered. They are casualties of an ecosystem out of balance and their real time vanishing is a slow white flag surrender.

This map records the branching organic shape and its particular and vital colours made by the forest’s birch, heather, and lichen. The colours have a vibrancy; might that they stir some folk memory or other, light the eye and lift the heart. Mending the thread to the linen is as an act of care and the map is a record of connection as well as an invite to see.

Language and its creative expression through song, lore and naming are colourful threads by which we can mend ourselves into the fabric of a place.

They invite us to know a place by its depth .

There is an old Gaelic story, old mostly forgotten, whose narrative arc follows that of the sky above my head. It belongs to Strathnairn; I can see sites in the story from my door.

In correspondence with this landscape, for this essay, I would like to speak to some of the ways in which finding and retelling this story have been an expansive exercise.

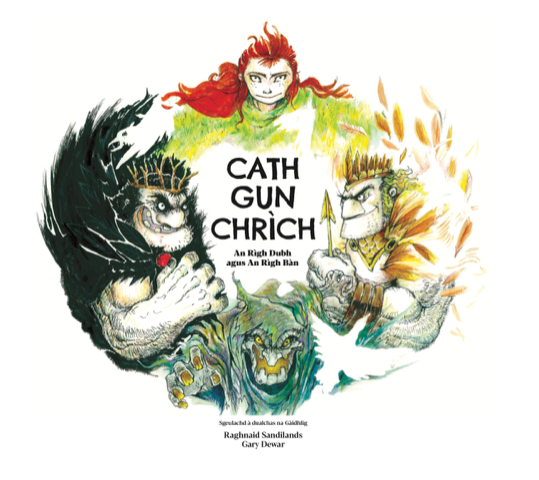

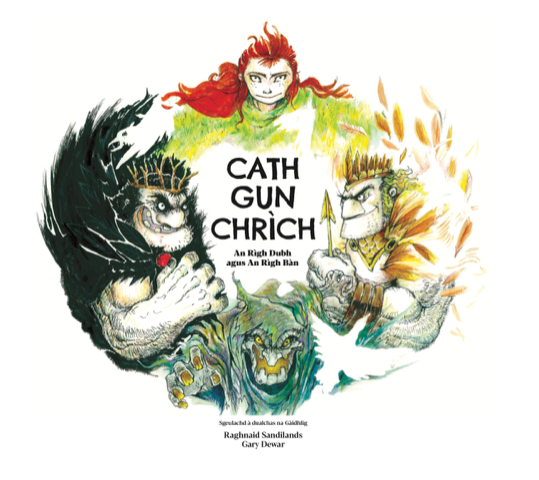

Cath gun Chrìch – A never ending battle

There is a story of two warring brothers, sons of a winter witch called a’ Bhean Gheur (the sharp wife), an iteration of a’ Chailleach, a female land goddess archetype associated with winter and elemental forces, found in stories across the cultural regions of Ireland and Scotland. Both kings love the same woman, Gnùis àillidh (bonny face) who embodies the spirit of the strath and blesses the crops and the animals. An Rìgh Bàn (the fair king) is an expert archer with a golden bow and herald of the dawn. His brother, An Rìgh Dubh (the black king), portent of the night and terrific fighter who can make himself invisible but for a single red dot suspended above his heart.

It’s an etiological origin myth, the type that explain natural phenomena – in this case the coming of the dawn, cycles of light and dark and the return of the seasons.The day and night revolve as one story cycle intersecting with and sharing an axis with the cycle of the seasons, symbolised by the figures of a’ Bhean Gheur and Gnùis-àilildh. There is a dynamic and contained momentum to this story – an older balanced configuration of time and nature, harnessed into a never ending battle.

I first came across this story, in an essay titled ‘Some Tales from Strathnairn’ in The Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. Andaidh Cuimeanach / Andy Cumming much loved and still remembered, gave accounts of historical events, characters, place name lore and a brief summary telling of the story . I have recently published a telling of this story as a picture book, with illustrations by Gary Dewar.

In this story the idea of darkness and winter is ever present; at once an invisible and a known force, one that is waiting. The image of a pulsing dot of red, representing the heart of An Rìgh Dubh, an oscillating point in the deep blue of the twilight, stayed with me from the first reading and the adjacent colours of red and blue that jar and appear to merge, blur and vibrate, as An Rìgh Dubh dancing in his delirium, was one of the details I loved.

The cry of the captured heroine being as the call of a ‘guilbeach deireadh ràithe’, a late season curlew is another. It’s a small detail but so vivid. It must have been that people readily knew the difference between the bird’s early bubbling call and eerie late cry. When I hear the late curlew’s cry now, it’s dimensions are expanded, it’s reverberations amplified some for knowing this story.

Creag nan Gobhar, the hill I see from my door is the scene of the dawn’s coming and the home of An Rìgh Bàn; expert archer, magical, sympathetic soul, bound to his mountain, unable to leave. He casts one golden arrow from his golden bow each day.

In the late summer, on a clear morning, the light first comes over the ridge of this hill in one fine beam.

There ought to be a word that speaks to a catch of wonder, a mix of awe and recognition, I felt when standing on the doorstep early one morning. Is this what people long ago had seen and encompassed into myth? It felt possible. This light dart as a visual echo, a start of illumination from another time, born of the dawn coming through the hills so; a fibre optic connection to other times and imaginations.

In this retelling, a’ Bean Gheur’s time coincides with the geese’s call and the silence of the ice-muted streams. Gary Dewar ’s illustration is of her as part rocks, part woman and in the wintery sky, a skein of geese rising.

Gnùis-àillidh is the female figure of abundance, nourishment and warmth. She embodies the land. The illustration of her cloak is one of grasses and wild flowers and the sky are song birds. Rowan, Scots pine and birch make up the forests.

The cover illustration has tricksy insignia, wee bird motif offerings for the children to find. The geòidh (geese) of winter, the summer smeòrach or thrush. The black of the cathag or jackdaw mirrors the black of the Rìgh Dubh and references one of the tops of his hill, Stac na Cathaig, crags of the jackdaw. My ornithologist friend tells me they are still here. The Curlew is the bird that bind the characters of An Rìgh Bàn and Gnùis-àillidh, that cries late on, on the cusp of summer and autumn. The Curlew is a foreteller of bad fortune in various folklores it seems. Merlyn Driver refers in his writing on curlews to the bird’s ‘special ecstatic sadness’ .

The Curlew’s cry is keener now, more poignant. The light through the hill is a que of sorts. The intense red of the nearly set sun is a more singular thing. The story enriches the world within its bounds. Here are new bearings by which to know the ‘poetics of place.’

Cultural loss is ecological loss

Part of the delight of having this story is that it is different to others from this place. It is not a story of depletion or loss – such as the accounts of emptied places, sites that mark acts of historic brutality. Stories about the wreckage and fall out of the years post Culloden are many.

Alastair MacIntosh has written about the last wolf dispatched by a man MacQueen in 1743 in nearby Strathdearn, serving in his essay as a parable of a place bereft, depleted of both people and biodiversity. He holds that cultural loss is ecological loss and quotes Arne Naess, Norwegian philosopher who speaks to the importance of recognising that

“… the human psyche extends into nature – what he calls the”ecological self’. Such “deep ecology” finds fullest expression in an ethics inspired less by duty than by the joy of engaging in “beautiful actions”. Central to such approaches is the rediscovery and expression of our creativity…”

McIntosh writes, “It is from the standpoint of this framework of interconnection with all that the loss of the wolf, or any other depletion of biodiversity, can be seen to be a loss of an aspect of our extended selves.”

If ecological loss is also cultural loss, culture and creativity may be a means to resist and to advocate, to expand what Robin Wall Kimmerer calls ‘the circle of ecological compassion’.

A known and named landscape

The cyclical story shape, significant in Gaelic culture and the pairing of female Celtic earth goddess types, that in turn create and destroy, point to this being a very old story. One other clue that this story has long since been in this place is that the winds are roused from Coille Mhòr (great wood) by An Rìgh Dubh in his frenzy of having captured Gnùis-àillidh and upended his brother’s happiness. The wind being roused from a wood and residing there was intuitive to my mind, and I did not appreciate on first reading the capitalised letters in the text and that this was a place name proper. The prevailing wind direction is down the strath from the direction of Coille Mhòr;

Today it is a ‘vanished wood’ and the peat is deep – a clue to the old roots of this story. Peat accrues at 1 mm per year and they say the peat in these parts can be 6 meters deep.

I took to looking for remaining ancient growth forest fragments in the high corries because the story lead me there.

(Photo of approx.1000 year old birch bark, Strathnairn. Photo R. Sandilands)

The gold lustre of birch 1000 years old found taken from an old peat bank near the Coille Mhòr.

A glance at the Gaelic names in the Monadh Liath and we find mention of aspen, alder, pine, hazel, birch, willow. These names speak of an ecologically richer, known and named landscape. There are hollows, groves, forests and tree cover in steep river gorges – a selection of those names within a 40 miles in radius from Farr to Killin, taking in Strathnairn, Stratherrick and the upper reaches of Strathdearn are as follows;

Coille Mhòr – the great wood

Càrn Caochan Giuthais – cairn of the streamlet of the pine

Allt an fhearna – stream of the alder

Allt Doirean Sgealbaichte – stream of the rugged grove

Creag Challtainn – rock of the hazel

Blàr na Doire – plain of the copse

Caochan Chaoruinn – streamlet of the rowan

Caochan Seilich – streamlet of the willow

Càrn Coire an Fhearna – cairn of the corrie of the alder

Lochan Allt an Fhearna – lochan of the stream of the alder

Caochan a’ Chrithinn – the streamlet of the aspen

Doire Meurach – branched grove

Càrn a’ Choire Sheilich – cairn of the corrie of the willows

Càrn na Seannachoille – cairn of the old woods

Beith Og – young birch

Coire Riabhach – brindled corrie

Doire Gheugach – branched grove

Allt Doirean na Smeòraich – stream of the grove of the thrush

In these places now, there are either no trees, a scattered few, depleted remnants and somehow still persisting ancient forests like Doire Gheugach. We live in an area that is plantation heavy, and the hills are covered with strange pocks, a bridling of muirburn for the sake of only the grouse and his dispatchers. In our immediate surroundings, with the silent monoculture plantations or on the near empty moor, it is hard to imagine how it might be otherwise.

(Photo of muirburn in Strathnairn. Photo R. Sandilands)

Knowing the language of the land gains you an affinity with other times, and also an understanding of what is missing. If Doirean an Smeòraich (small grove of the thrush) is no longer in existence, silence is the soundscape, not bird song.

It follows that these names are an indication of what could return. As Robert MacFarlane reflects,

‘Words are not just a means to describe the world but also a way to know and love it. If we lose the rich lexicon then we risk impoverishing our relationship to nature and place. What you cannot describe, you cannot in some sense see’

Finding Fragile Forests

‘Develop a meaningful relationship with the natural world, and you never stop seeing and perceiving news things… It’s a cup that never runs dry.’ Eoghan Daltun

Conserving these ancient ecologies is vital. The latest IPCC report (March 2023) shows that protecting existing forests is far more important than new plantations. Their diversity is what gifts them resilience and makes them less vulnerable to threats posed by climate change.

Thinking about the Coille Mhòr and the wealth of place names was a catalyst for a day of modest activism; a walk to an ancient forest in Coire Gart (the corrie of the enclosure) with ecologist and passionate advocate for these places, James Rainey. ‘What can we do?’ was a question I’d asked him. His reply was simple: ‘help people to see’.

A simple recipe for a gathering to try and do that was as follows; a homespun poster, a call out to experts on local history, Gaelic place names and bird life, the promise of some music and song, teas and baking and a local hall to land in afterwards. The poster was a provocation, knowing many locally would ask ‘Stratherrick’s ancient woodlands…what ancient woodlands?’

There were memorable moments. Coire Gart was high off the main trail, a good hour or so walk through screens of thick plantation spruce and larch. There were deer fences and locked gates to negotiate but we came by those obstacles with a quiet resoluteness. There were visible lessons in how to fail to plant well or protect; a crop of empty plastic tubes on opened peatland. When we reached the edge of the old birch, some children climbed up to sit in the branches and listen, an unbounding upwards. Someone shared out greim an t-saighdeir (soldier’s bite) wood sorrel.. There was an eagle in the sky and cuckoos in the forest while we took our lunch. The youngest and the oldest in the party walked and talked a while. Our eyes were hungry for that new green of May, the textures of the lichens and that absolute organic shape of the forest in the land.

(Photo of walk group setting out to Coire Gart (corrie of the enclosure) in the distance. Photo R. Sandilands)

(Photo; Ancient woodland in Coire Gart (corrie of the enclosure). photo R. Sandilands)

This day was a celebration of the human as well as the natural ecology of these places; knowing the Gaelic names, learning about the forest as shelter and source, how they way-marked older routes though the land. We kept good company; peatland, bird, and insect life experts had come. Small children were heaved over fences and out of bogs. Afterwards, in the hall, we had a story for two from Alec Sutherland, Errogie, a laden table and tunes on whistle, fiddle and accordion. To close the day young voices sang, a Gaelic song about trees with a communal chorus – a verse each for rowan, oak, blackthorn and rosehips, just for the joy them, written by two young friends.

Òran nan Craobh (song of the trees) (listen here)

We came and saw, as James had suggested, and any claim of care for these fragile forests can perhaps be made in chorus and with surer voices.

“Caring is not abstract. The circle of ecological compassion we feel is enlarged by direct experience of the living world, and shrunk by its lack.” – Robin Wall Kimmerer

‘If you know the story you love the place, and if you love the place, you look after it,’ a friend once said, after a lively night of local music, story and debate we had hosted in another village hall up the road, where land reform in Scotland was the topic in hand.

Poet and ethnologist Cáit O’ Neill McCullagh has spoken about stories of places and people as one of the ways “we nurture living and ongoing memories of those who stepped before, helping to both make and renew people and place.” They can be a means to ‘call out the banal systems of place ownership that obliterate becoming and belonging.’ We can nurture more, we can belong more. I like Cáit’s generous manifesto.

The story of that place might be many things; what it was, what it is, what it could be or be the sort of story that plays out in a landscape, of mythic scale.

I asked children, “whose story is this?” Theirs, they had said. In the summer they had come to the local Fèis to make a huge charcoal map of stories and their places. Perhaps in their answer, was the kindling of knowing that this was a fine and rare thing, a community’s to keep, gifted from other times, shared that day and in this place.

The story is a beautiful orientation for them, an invite to look to these hills or their sky; a story that introduces cosmic scale characters to that first world that so often nourishes memory and cheer.

The exchange between myself and one son became part of the opening frame of the book. He had stood bleary eyed in the first light and asked ‘A bheil An Rìgh Bàn air èirigh fhathast? (Has An Rìgh Bàn woken up yet?). It was hard to be annoyed even at that early hour, when the question was all poetry. The end pages show my other children clambering on the rocks and behind them all the shades of a sky revolving to meet the day. Cultural ownership might look like this – the confidence and freedom to clamber all over your place, without inhibition, to have places to go, discoveries to make, people to meet and the technicolour of such stories backlighting your space.

‘Stories that guide us’

This old story from Gaelic tradition is full of sense rich details; the vivid redness of an almost set sun, the shadows lengthening as Gnùis-àllidh walks, the wind roused by fury, the cry of the late season curlew, the pre-dawn coolness, the dew drops as tears shed on the land, the first beam of the dawn, the beginning of the story….

The story plays out its timelapses in this landscape. Light, colours, sounds, reverberate with something more for knowing the story; an older love of these places, memories of a richer ecology, when the wind lived in the forest that is no longer stands, when there was more time to know the distinct curlew cries.

“It’s not just the land that has been broken, the land is broken because our relationship to land is broken. Healing of land, yes, and resistance to forces of environmental destruction. But, fundamental to that at the deepest level is this notion of our collective psyche. It comes to world view, right back to stories that guide us into thinking about what is our relationship to place.” – Robin Wall Kimmerer

This story has a world and connections forming around it again; whereby people know the story again, a friend remembers and writes a fond account of Andaidh, the story keeper, they go looking for old forest, gather in the hall, call in favours, bake, play tunes, sing for the love of trees, make space for language, make art, make more community and living culture. The book launch itself was like a wedding of the story to the place again – there were pipers.

Gaelic, like all indigenous languages, and stories from the culture, have much to say in terms of seeing and naming and knowing the natural world; the detail speaks of an intimacy and care.

Cath gun Crìch is a story in praise of the cosmological shifts of the world. It’s worth seeking out these stories, there are sustaining gifts; ‘cho cinnteach ’s a tha an saoghal a’ cur car’, as sure as the world turns, and the light returns, they are there. Noticing some of these same things still and in situ, is to feel connected to ongoing dynamics of this place, the ecology and people. It’s a surround-sound multi-sensory experiential hyper-local myth. Keep the AI filtered reality goggles, I’m away out the door to meet the dawn.

In chapter 6 of Celts: Art and Identity (British Museum and National Museums Scotland, 2015) the authors write that, before the Romans arrived:

“there is no evidence that deities were conceived as human: hidden faces and figures occur in much Iron Age Celtic art, but recognizable humans were exceedingly rare in pre-Roman Britain.”

Romans apparently shaped much of the forms of worship, and spread local deities they liked (such as Epona and Toutatis) to their camps, cities and frontiers. So when a humanified Scottish deity appears to metaphorically embody some natural phenomenon such as Night, its pre-Roman ancestor may have been more literal. In the humanising of our worldviews, which continued to the extreme in Christianity, the Romans may have committed one of the most heinous crimes against nature in world history.

Another wonderful piece, thank you. And thank you Bella.

Taing mhòr a Raghanid. Pìos prìseil dha rìribh.

Sin mar a tha i.

Aibhiseach.

Moran taing a rithist a Raghnaid