We can’t just call it a Wellbeing Economy and make it so

Post-growth economics is becoming a more popular radical alternative to economic orthodoxy. But ‘We can’t just call it a Wellbeing Economy and make it so’, argues Michael Weatherhead Co-Founder and Development Lead at Wellbeing Economy Alliance.

Since the appointment of the first cabinet level post for the Wellbeing Economy, fans of widely debunked 80s-inspired trickle down economics have been quick to dismiss the Wellbeing Economy approach through gross mischaracterisation.

On the one hand we’ll take it as a compliment that this once radical alternative is today seen as a threat by those who want to maintain the status quo. At the same time there is a risk that business as usual is legitimised through Wellbeing Economy-washing.

The extent to which Scotland is making good on its commitments towards a Wellbeing Economy is a story for another article, but as one of the co-founders of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance I want to set the record straight about what a Wellbeing Economy is and what it isn’t.

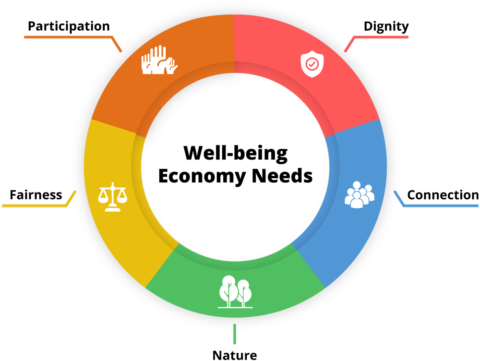

A Wellbeing Economy is one designed to meet the needs of people and planet. It would prioritise meeting these five fundamental needs.

- Dignity – everyone has enough to live in comfort, safety, and happiness.

- Fairness – justice is at the heart of the economy.

- Participation – citizens are actively engaged in their local communities and locally rooted economies.

- Purpose – Institutions serve the common good and create value.

- Nature – a restored and safe natural world for all life.

I’m going to focus on the one that we at the Wellbeing Economy Alliance feel is not fully understood or articulated in either the many opinion pieces written of late on a Wellbeing Economy nor the government’s interpretation of it – Nature.

The Scottish Government has targets to reduce climate-damaging emissions to net zero and have restored and regenerated biodiversity across the country by 2045. But in Scotland we are already using the equivalent of multiple planets worth of resources in the generation of our economic wealth. This overuse of resources, which is largely driven by economic growth, is having a detrimental effect on the health of our environment. Running down nature to the point that ecosystems are collapsing whilst simultaneously pressing down on the pedal of economic growth is the equivalent of taking the finish line of 2045 and pushing it further and further away. In short, the government has no chance of achieving our environmental targets – a necessary but in no way sufficient condition for a Wellbeing Economy – without adopting pathways that restore nature and slay the myth that continuous economic growth on a finite planet is possible.

A healthy relationship with growth needs to be established. Examples of desirable economic activity are an expansion of community owned green energy production, home insulation and more public transport. Examples of harmful economic activity are new oil fields (as if that needs saying, but it appears it still does), expansion of private car ownership…remember that fact that we are already using too many of earth’s materials to sustain our current lifestyles…and fast fashion.

A future Wellbeing Economy would see a far greater proportion of businesses acting as though the natural world were a key shareholder, as Patagonia now is. Leaders are increasingly recognising resource constraints and identifying ways that goods can be offered as a service, be designed for disassembly (ready for reuse) and extend the lifespans of their products. They are innovating to find ways to both restore nature and be financially healthy. Just look at WEAll’s ‘Business of Wellbeing’ guide or those businesses featured in the ‘extra’ episode of David Attenborough’s ‘Wild Isles’ to get inspired in this regard.

So, staying within earth’s limits and helping restore nature now starts to look like a whole lot more than a Nordic 2.0 economic model of large-scale tax redistribution and more generous public services. We need to fundamentally rewire the economy so it genuinely puts people and planet first.

One cannot disagree with the good intentions, but the realisation of these aims comes up against some significant obstacles. We like to keep warm, cook nourishing meals, and watch TV or read books. We may go to work. What is necessary to enjoy this simple life is cheap energy.

Are wind farms and solar panels not a bogus sop to those who wish to us stop using oil, coal, and nuclear energy generation?

To make the new world will require greater change than all of the changes that followed the invention of the steam engine. The Industrial Revolution was driven by the desire for profit, and for the fun of it, as well, maybe.

Yes the 5 aspirations above look good. And there are various moves to consume less, and use the 5 ‘R’s or is it 6 now – reduce, reuse etc. We need stories of ways to live, or move towards living in a finite planet. More positive stories of where people have achieved low impact living. It’s not easy to get out of the various dependencies like needing a car if living in rural area etc. Changing the psychology of everyone in a rural village or locale in order to think of sharing transport, collaborating on food growing (see Abundance Borders for fantastic community growing iniatives), or building local energy networks, is a continuous task. Changing our psychology to be responsible rather than expect the state, charities or worse, private companies to care for us in all the numerous ways we seem to need. We could do with more off-the-wall ideas like – can medical care be devolved to local areas (local health cooperatives anyone?), what about reviving a ‘bare-foot doctor/carer approach? So much to learn and share….