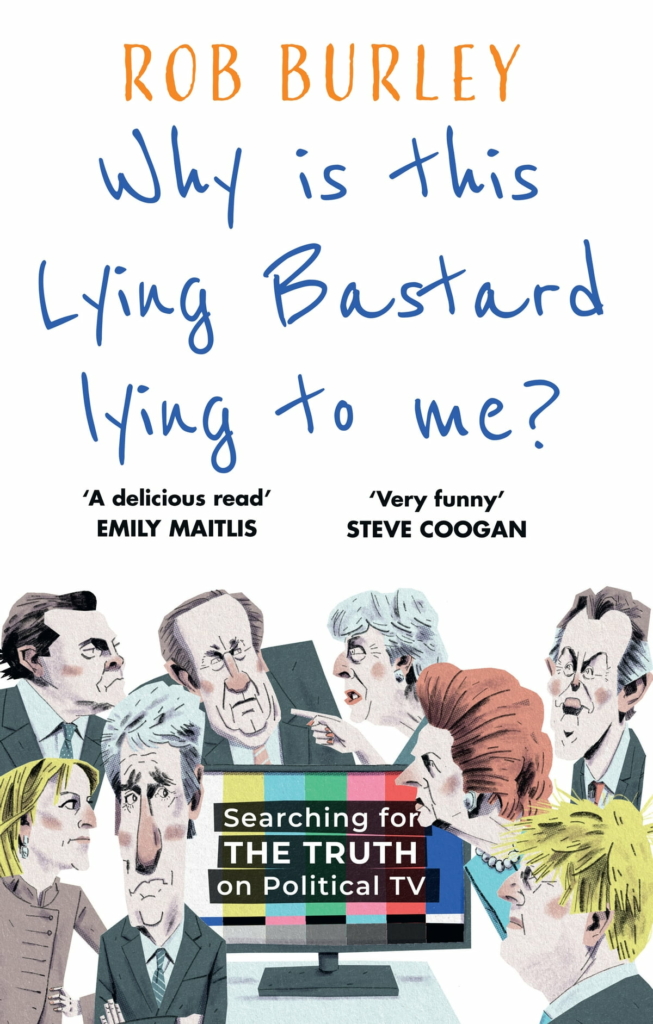

Why is this Lying Bastard lying to me?

The Distinct Smell of Burning Pants, the BBC and Telling Political Lies

Why is this Lying Bastard lying to me?, Rob Burley, Mudlark £16.99.

Reviewed by Ken Macdonald

People just love being lied to.

Or at least a significant proportion of them do. How else to explain an era in which proven liars are elected to office, lie even more when they’re there, then keep on lying after they’ve been booted from power?

This is the age of politicians who find themselves ambushed by a cake, who can see weapons of mass destruction where none exist, who claim to be able to declassify documents just by thinking about it, and then cry ‘witch hunt’ when they’re found out.

Rob Burley has spent his career “searching for the truth on political TV”. That’s the subtitle of his book, the ‘lying bastard’ quote of the title coming via grand inquisitor Jeremy Paxman. Burley has worked with, if not them all, then certainly most of the ones who matter: Paxo, Brillo, Frosty, Andrew Marr, at least one Dimbleby (Jonathan). Latterly the cast has expanded to represent the other half of humanity: Emily, Kirsty, Laura, Beth.

The book pulls off a difficult trick. It is both a personal memoir and a history of the long form political TV interview. Along the way it takes us on a swift tour of UK political history from the rise of Thatcher to the weird fever dream that was the Truss administration, which still has the feel of some kind of collective hallucination.

It holds back the curtain to give us a keek at the intricate courtship dance which may eventually entice a big political beast to sit down in a studio with a big-name interviewer. As Burley points out, there’s nothing in the constitution that says they have to do it.

Sometimes the process is as simple as picking up the phone and asking someone if they’ll come on. But not very often. Typically, the politician’s people will want to know much more than the where and when. The areas to be discussed, who else is on the show, and not least who will be asking the questions will all have to be sorted out. Sometimes it takes weeks or even months, sometimes it happens with unnerving speed.

And sometimes the process starts the other way round. One of Burley’s tales takes us back to the time when New Labour’s rose was in first bloom. In early 1997 the then Formula One boss Bernie Ecclestone had donated a million pounds to the party. Nine months later, and in power now, Tony Blair ordered his health secretary Tessa Jowell to exempt F1 from his government’s tobacco advertising ban.

The optics, as they say nowadays, were dreadful. It looked like a big donor had bought government policy and that Blair had covered it up. Blair’s media enforcer Alastair Campbell decided a big, set-piece, TV sit-down interview was the only way to draw the line and move on. His boss needed to take a kicking.

Campbell decided that David Frost was too chummy and couldn’t be trusted to put the boot in properly, so he called the BBC’s On the Record and asked if John Humphrys would like to interview the PM the following morning. Who wouldn’t? Humphrys did his customary Rottweiler tribute act, but Blair went all Bambi-eyed and expressed his hurt that anyone could think he was anything other than an upstanding chap. Then he deployed what became a classic Blair soundbite:

I think most people who have dealt with me think I’m a pretty straight sort of guy, and I am.

Except he wasn’t. Blair told Humphrys that a decision to refer the donation to the standards commissioner had taken place before the press had inquired about the story. That was not the case or – as the uncharitable might put it – Blair lied.

It is central to the book’s thesis that the long form political TV interview is the key that unlocks the political process, exposing it to the gaze of the voters. But that only works if the interviewee is telling the truth or is caught telling porkies. Blair’s economy with the truth was exposed years after the parade had gone by.

Burley’s book is well sourced, insightful, anecdote-packed, occasionally sweary and frequently very funny indeed. It is peppered with great tales such as the time George Osborne asked for a selfie with Jeremy Corbyn (I won’t spoil it further).

If he sometimes makes it all sound like a game that’s not his fault. It is. A big, London-centric, testosterone-fuelled, two-party game (although the SNP get a few drive-by mentions and Paddy Ashdown gets a cameo, lying in his teeth to Jonathan Dimbleby on air and admitting it in the green room afterwards).

Burley rose from being a humble researcher at ITV to edit its political programme. Later, the BBC: Newsnight, Andrew Marr’s show, running the corporation’s political programmes department. After that came LBC and Sky.

He makes it all sound fun. Exhausting, tense, high stakes, but fun. He shows us the enormous effort a production team puts into preparing for a big sit-down. Brian Walden and his team would have a huge briefing document outlining every possible response to every question, each response trailing its own sequences of possible responses. It looked like a family tree. (By contrast Andrew Marr prepared thoroughly but didn’t take a list of questions into the studio as looking at them would break eye contact with his interviewee.)

He devotes two chapters to the thrilling – no, really – tale of Walden’s ITV interview with Margaret Thatcher in 1989. In events which seemed pivotal at the time but these days might as well have involved dinosaurs, her Chancellor Nigel Lawson had quit over the influence of the PM’s economics adviser Sir Alan Walters, perhaps best remembered – if at all – as something of a Noddy Holder lookalike.

Thatcher and Walden were friends. Despite being a former Labour MP Walden had written admiringly of Thatcher’s policies. He had even clandestinely given a script polish to one of her election broadcasts, a big journalistic no-no. But on this day, perhaps stung by criticism that his many previous interviews with her had been too soft, he went for her.

He rattled her and made her look shaky. She described Lawson as “unassailable”, to which Walden pointed out that he wasn’t, because he’d gone. She’d chosen Walters over Lawson. She came across as out of touch and a bit silly. The cracks had started to show in the Iron Lady. It was great telly. She never spoke to Walden again.

But to what end? Happily, Burley eschews the self-important American trope that journalists should ‘speak truth to power’. He’s much keener on the idea that journalists should present truth to the voters and let them sort it out with the politicians.

That’s spot on, but is the long form TV interview the best way to achieve it? The Iron Lady may have begun to rust that morning but she remained in power for another thirteen months. Similarly Blair, despite his kicking from Humphrys, went on to win another two elections.

Even if the politician is eviscerated live on air, it’s the equivalent of the tree falling in the forest if there’s nobody around to watch it.

The traditional home of the big set-piece interview is Sunday morning. It began in the United States in 1947 with NBC’s Meet the Press. The UK had to wait until 1972 before John Birt’s Weekend World chin-stroked its way into the schedules.

A Sunday morning slot enabled a commercial broadcaster to tick the public service box at a time when advertising revenue wouldn’t take too much of a hit. Watching a Sunday morning talker was for politicians, political journalists, and anoraks. The rest of the world was hungover, possibly still in bed, at the supermarket, or otherwise having a life. Any big exclusives in the Sunday papers could be mopped up live in the studio, and if anything newsworthy was said by a politician on the show it could be turned around for the news bulletins later in the day. Sundays tend to be terribly slow in broadcast newsrooms.

And that’s the problem with the big sit-down grilling. Most of us only get to see a few, filleted seconds later in the day. It was true back in 1947 and even more so now in the age of supposedly ‘social’ media. As I write, the BBC News website is inviting me to watch a summary of Boris Johnson’s career in 72 seconds.

The BBC was not alone among broadcasters in that it once reflected the post war consensus that the politics of the far right were beyond the pale in a liberal democracy. But in recent years it sometimes seems that the builders have been into the BBC’s public forum, shifting the Overton window further to the right. Promoters of intolerance, authoritarianism and racism are given platforms in a way that hasn’t been seen for decades. Once such types were regarded as jolly bad eggs of the kind who once flew over here in Heinkels hoping to kill our grandparents. Now it seems fascism is just another gaily laid out stall in the great marketplace of ideas.

Perhaps I am wrong. Perhaps there is balance. Perhaps anarchists and Marxists and other voices from beyond the centre left are never done popping up on Question Time to haul capitalism over the coals. If so, apologies. I must have missed those episodes.

Burley takes head-on the frequent accusation that the BBC ‘created’ Nigel Farage by giving him undue prominence. His counterargument is that UKIP’s prominence was dictated by their electoral popularity and they were a one-man band. I beg to differ. Many others in the band were racists, ranters, xenophobes and the otherwise unhinged. Perhaps the BBC might have served democracy better by pointing a camera at one or two of them in prime time. Instead we got Farage again and again.

Burley’s background is Labour and Remain but he has little time for the idea of a BBC as a vast right-wing conspiracy. He says prominent right wingers such as Sir Robbie Gibb and Andrew Neil were in a minority:

While some high-profile BBC journalists came from a Conservative background, and others left the BBC to go and work for the Tories, the cultural and political centre of gravity of the BBC is liberal and ever so slightly to the left.

It is worth noting that this may put the BBC in line with the political complexion of England, but as a reflection of the rest of the UK it’s completely skew-whiff. And again, there may be an equal number of overtly centre-left people in the senior managing and presenting ranks of the BBC that I’ve failed to spot. OK, I’ll give you Gary Lineker.

The current director general – and former Tory candidate – Ed Davie does not emerge well in Burley’s telling:

The perception that the BBC is too close to the government has only grown under his leadership, and troubling allegations about how BBC Westminster responds to pressure from the government have added to these concerns. The BBC is a wonderful institution that we need to cherish but sadly, in 2023, it’s not a happy ship.

This is unsurprising, given that Davie cut his teeth (an no doubt rotted other people’s) in the soft drinks trade. He has never made a programme or compiled a news bulletin in his life, and it shows. I was once told by an editorial bod that the BBC ‘must bend like the willow’ according to the prevailing political wind. But you can only bend the tree so far before it snaps.

Despite everything, Burley remains a true believer in the power of the big sit-down interview as a driver of democracy. In his book, politicians may lie at the time but ultimately they will pay the price.

There may be another way in which these big grillings are useful – when they don’t happen. Burley reminds us that Boris Johnson famously avoided a major Andrew Neil interview during the 2019 election campaign. So did Liz Truss as she fought to become his successor. The rest was hysteria.

Silence instead of scrutiny may be the loudest warning of all.

“This is unsurprising, given that Davie cut his teeth (an no doubt rotted other people’s) in the soft drinks trade.”

Excellent line! Made me laugh. Looking forward to hearing more from Mr Macdonald, now that he is freed from the BBC’s “impartiality” cosh and able to speak more openly. Book sounds interesting, thanks.

People seem happy to vote for liars as long as the liar is pushing an agenda they believe in (because of the lies they’ve read).

As I read this book review I heard Ken’s voice in my head all the way through. More from Ken please.

Great read. Thanks for the review.

Interesting take, but I haven’t read the book. Does it go into detail about a more dynamic questioning approach, such as the Socratic method? Philosophers are generally trained in spotting sophistry (it does not stop any from indulging in it themselves but being caught out should be professionally embarrassing). The general idea is to draw out one’s thinking through cooperative, non-abusive dialogue. Any inconsistencies or controversial points can immediately be addressed. It does require concentration on what the other is saying (or not), and sometimes flexibility, responsiveness, curiosity, laterality, imagination, persistence and naivety will be more successful for questioners than extensive preparation on expected content. Definitions are often requested to avoid talking at cross-purposes.

You make a good point about Philosophy. All the courses in Philosophy I have taken have included substantial sections on fallacies and sophistry, and, to me, have been very important and educative parts of the course.

Most politicians who attend Oxbridge colleges take PPE – philosophy, politics and economics, not personal protective equipment which should be issued to all of us when on Oxbridge educated politician speaks or is interviewed. Indeed, perhaps, like cigarette packets a health warning should be tattooed on their heads to alert us before they speak.

I suspect that they, too, find the fallacies and sophistry sections of the course highly interesting, but, unlike my liking for these sections, their liking is to enable them to learn how to deploy them in discussion and debate. The tutor system used in Oxbridge is practice in deploying, in an apparently honest and sincere way, the fallacies to make black seem white. Alexander Boris de Waffle Johnson probably won the prize for the most persistent liar.

@Alasdair Macdonald, I suspect you are quite correct.

My own confidence in BBC Scotland’s news coverage has not recovered from a small incident in the run up to the Iraq War. Walking up The Mound in Edinburgh, I saw a BBC camera crew filming an anti-war protest. The number of protesters was in single figures. This ‘story’ led the BBC Scotland news that evening. You would not have realized the size of the ‘crowd’ from the way it was filmed. It was not considered newsworthy by either The Scotsman or The Herald next day.