Learning from Le Paris du 1/4 Heure

This week saw praise rain down on Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo. She is the driving force behind Le Paris du 1/4 Heure – the 15 Minute city which aims to create viable low-carbon communities. As France riots and belief in politicians here plummets, she is that rare thing in an age of hopelessness, an inspiration.

She is breaking the mould on several levels. First running on – and getting elected on a specifically radical environmental programme is a rare thing. Second, successfully delivering it is unheard of. But reports this week show car use in Paris down 40% over the last 10 years, air pollution is down 45%, cycle lanes are up from 200km in 2011 to over 1100km; 300 ‘school streets’ are coming and there are major plans to make streets safer for children and older residents.

How is she bucking the trend?

Hidalgo’s successful 2014 and 2020 mayoral elections in Paris have been a revelation in running on a ticket of positive change and then embracing it. She has got people’s buy-in and then delivered. In the words of Hidalgo, “Big cities are responsible for 70% of greenhouse-gas emissions. We have a political responsibility, as mayors, to say, ‘We must act now’”.

What does it look like?

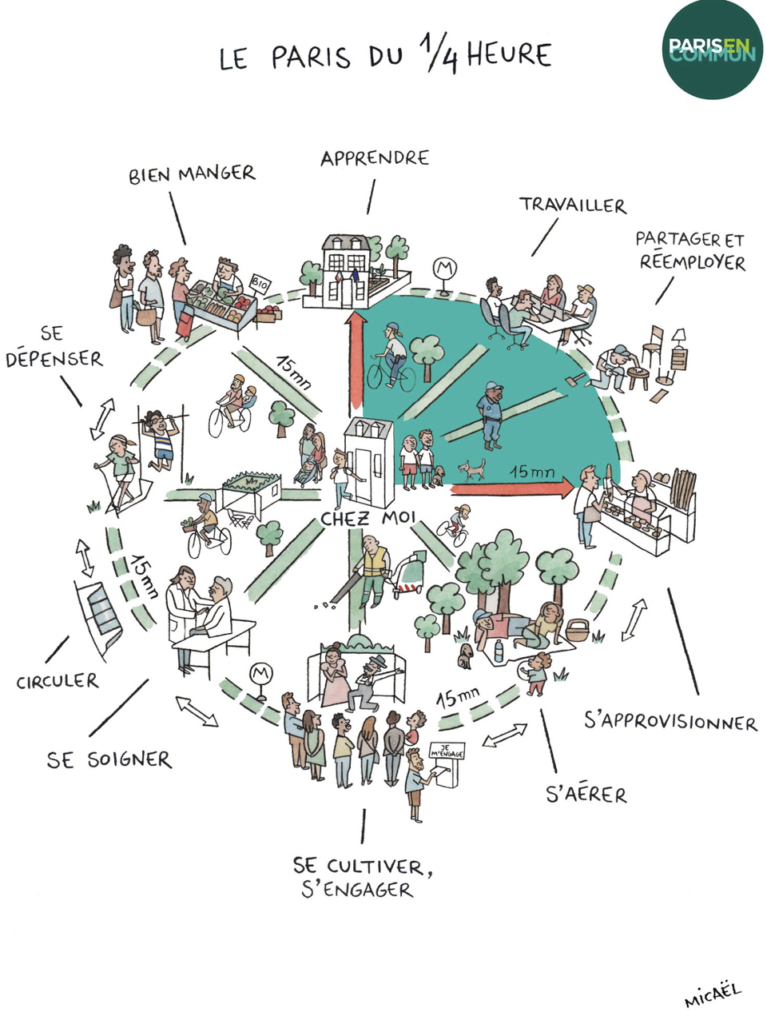

In a world where we work less and travel less and pollute less, it would mean that we have most of our basic needs for work, education, leisure, sport, entertainment localised.

The inspiration behind the 15-minute city idea is the Professor Carlos Moreno, from la Sorbonne who believes the “core of human activity” in cities must move away from oil-era priorities of roads and car ownership. To do this he argues: “We need to reinvent the idea of urban proximity. We know it is better for people to work near to where they live, and if they can go shopping nearby and have the leisure and services they need around them too, it allows them to have a more tranquil existence.”

The ideas have been embraced by Hidalgo who wants to encourage more self-sufficient communities within each arrondissement of the French capital, with grocery shops, parks, cafes, sports facilities, health centres, schools and even workplaces just a walk or bike ride away.

Called the “ville du quart d’heure” – the quarter-hour city – the aim is to offer the people of Paris what they need on or near their doorstep to ensure an “ecological transformation” of the capital into a collection of neighbourhoods. This, Hidalgo argues, would reduce pollution and stress, creating socially and economically mixed districts to improve overall quality of life for residents and visitors.

The Ville Du Quart D’Heure concept is based on Moreno’s idea of “chrono-urbanism,” or having leisure, work, and shopping close to home. This means “changing our relationship with time, essentially time relating to mobility,” says Moreno.

Moreno says he was inspired by the urban theorist Jane Jacobs, author of the 1961 classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

“A neighbourhood, she wrote, is not only an association of buildings but also a network of social relationships, an environment where the feelings and the sympathy can flourish.”

Jacobs was influenced by Lewis Mumford, himself a disciple of our own Patrick Geddes. We have our own rich tradition of urban theory and civics to draw on here.

“The quarter-hour city would reduce two serious problems plaguing many Parisians: the air pollution that kills 3,000 people a year, which is largely caused by car traffic, and the many hours lost in transport suffered to go to work,” says Delphine Grinberg, a member of Paris Sans Voiture (“Paris without cars”).

These moves are happening elsewhere too. Feargus O’Sullivan has written:

“Barcelona’s much-admired “superblocks,” for example, do more than just remove cars from chunks of the city: They’re designed to encourage people living within car-free multi-block zones to expand their daily social lives out into safer, cleaner streets, and to encourage the growth of retail, entertainment, and other services within easy reach. East London’s pioneering Every One Every Day initiative takes the hyper-local development model in a slightly different direction, one designed to boost social cohesion and economic opportunity. Working in London’s poorest borough, the project aims to ensure that a large volume of community-organized social activities, training and business development opportunities are not just available across the city, but specifically reachable in large number within a short distance of participants’ homes.”

What would the “ville du quart d’heure” look like in our cities?

Sharing some good news this week triggered a wave of negativity from some on Twitter. The gist was “this could never work here” – a strain of the “Don’t you get above yourself” syndrome that still holds Scotland back. The problem, I had explained to me, was the weather here you see. Despite having literally invented urban planning a century ago, Scotland would be uniquely incapable of (re) designing our own cities. This is exhaustingly stupid. It’s learned failure.

Of course the Hidalgo/Moreno ideas would not transfer across seamlessly. Every design needs its own local variant. That’s the point. But to argue that “we couldn’t do it here” moves us into a sphere of inferiorism and decline. We could and we should and we must.

The real obstacle to the implementation of radical re-design of Scottish cities along these lines isn’t ‘the weather’. Our local authorities and our ‘city fathers’ (and mothers) have been both starved of real resources and also demonstrated terrible decision-making for a long time (these things are not un-related).

The problem for the implementation of 15 minute cities – a necessary and radical reconceptualization of life in cities for a viable future – is about class not rain. Not every neighbourhood is heaving with cargo bikes and community gardens. But rather than make this a mark of failure it could become a metric for success. If the core idea is that everyone should have all of the necessary on our doorstep: our work, play, education, food, space, all in a safe and affordable and accessible way, then this is the measure of what communities demand. The first step for decentralising communities within Scottish cities is democratising them. If Low Traffic Zones (LTZs) sometimes feel like impositions, despite popular support to introduce them, that is because those disaffected about our cities are, by definition, not involved. The obstacle to radical re-imaging our cities – or our coastal communities – is not the ideas for change – it is how they land or how they feel they land. The answer is for these solutions to be driven from below, by the people who ‘own’ and run their communities. Nothing else will work.

In an urban environment Hidalgo is facing runway success. Despite the hysteria of the car lobby, the weird backlash of the libertarian cults and the scepticism of everyone to (any) change – actually less cars in cities and creating empowered communities and neighbourhoods is an inspiration.

And presumably that means electric power is optimally suited just for utility vehicles and mass transit rather than the consumptive dead end of private motor cars, SUVs and limousines.

The idea is not new. The OU course “Understanding Society” showed how having very nice upmarket housing in city centres would attract businesses to the cities and town centres. This is because business owners have no wish to have long commutes to work. Has that turned out well? Certainly in the places in the studies the slums disappeared, crime rates dropped and city centres became nice places to be.

However, Parisian suburbs are looking too clever this week. I do not know how Central Paris is faring, but I won’t be going there anytime soon.

Le Corbusier’s “Radiant City” became the Red Road flats.

Edinburgh is full of cargo bikes, there are three ‘community gardens’ near to me (not that anyone is interested in them appart from the gardeners – we have great big public parks). There is also considerable ongoing expenditure on seperated cycle lanes and paths. There is an incoming central LEZ. In any case, in no way is Edinburgh a car-friendly city, and we have good council-owned public transport (that makes a profit). This all came about by organised long-term local campaigns that interact with the council.

In Edinburgh there is usually more pedestrians than cars.

Where there has been little or no campaigning: In Aberdeen you cycle on the pavements because the motorists tend to be nutters, and there are almost no pedestrians in most places. There isn’t even a 20mph speed-limit in most places. It’s car city. The even strongly considered turning Union Terr Gardens into a multi-story car park.

Is there any published evidence of impact on inequalities? The mayorality is restricted in geographic scope and there is a perception that the interventions have benefited a very privileged population in Paris.

Is there any published analysis of the impact on inequalities? My perception is that this has made improvements to parts of Paris that are already incredibly privileged, and that it doesn’t reach the banlieu.

Here is the Scottish Gov’s 20min neighbourhood living consultation, if anyone is actually interested:

https://consult.gov.scot/planning-architecture/draft-local-living-and-20-minute-neighbourhoods/

Unfortunately, Paris has gone wrong, as has France. Social cohesion has been wrecked. Without social cohesion there is no stable order. Without order whatever you try to do to improve a city as a place in which to live and work is doomed to failure, I fear.

At the moment a debate is going on about the causes of loss of social cohesion and respect for the republic and the forces of law and order. Presumably this will eventually result in various measures which will not work if all relevant matters cannot be discussed openly. An opinion poll has found that 59% of French people consider the recent disorder to be related to excessive immigration and a large unassimilated population of people who feel no loyalty to or respect for the state, although the government apparently disagrees.

To give a sense of how serious the problem is, however one may define it, I need only mention a presidential visit to a suburban police station, where that nice Mr Macron asked who was influencing the rioters to stop the rioting as the situation began to improve. The reply from the police was that it was certainly not political leaders but leaders of drug gangs, who had evidently decided that it was time for the rioting to stop, as it was beginning to have an adverse impact on their business.

Paris is certainly not looking too clever right now.