The Scottish Cultural Cringe (non-fiction)

A deep analysis of the forces that has given rise to Scotland’s sense of cultural self hatred.

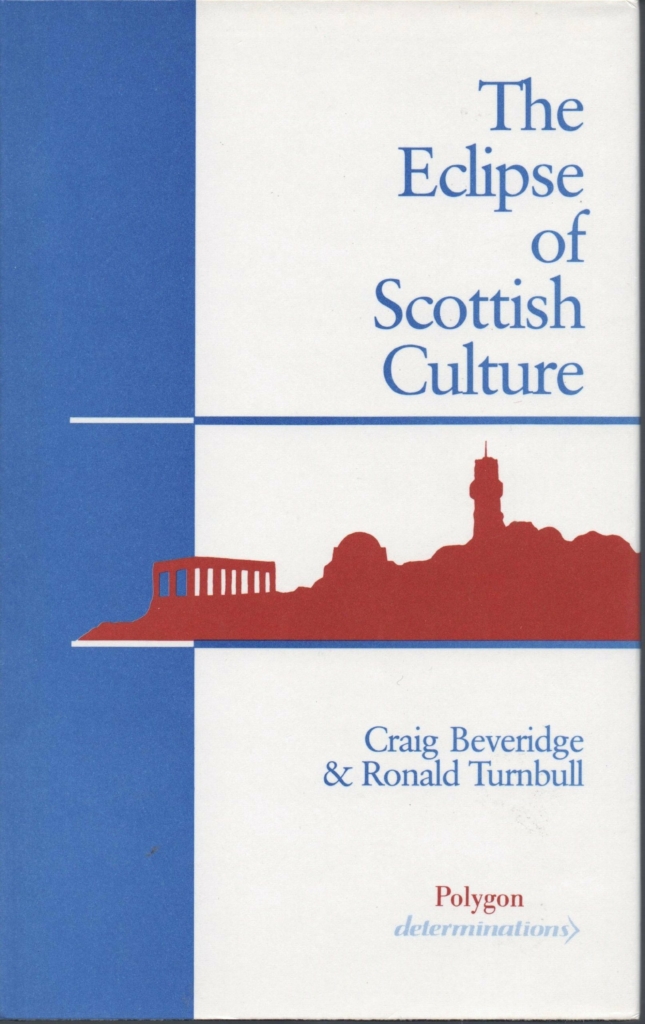

The Scottish Cringe as described by Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) refers to the Scots lacking personal and political confidence in their ability to govern themselves. Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) argue the Scots suffer from a sense of psychological inferiority in which Scots have come to see themselves and they are seen by England i.e. as being inferior to and dependent upon the largesse of England. Sociological theorist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence can be deployed as another means to understand Scotland’s sense of culture inferiority because this notion of Bourdieu is used to explain how the more powerful are able to structure the self-perception of the weak, so that social groups are not only conquered or colonised militarily by a more powerful nation as there is another defeat or war waged that is done via or by culture (Bourdieu and Waquarant 1992) i.e. Scots collude in and co–produce their subordination because they sincerely believe their culture is not equal to that of England. On this matter, Carol Craig (2003) argues that Scots are harshly disparaging to their own culture and by doing so create apprehension in the Scottish persona.

Another key term utilised by Bourdieu (1979) is the concept of habitus that describes how and why people become subdued by social conditions and exercise amor fati rather than rebel against their subordination because their habitus aligns the agent with his objective possibilities and so his subjectivity ‘falls into line’ with their objective life possibilities; so, that rebellion becomes an unrealistic course of action.

In this regard, Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) applied Franz Fanon’s (1967) notion of inferiorisation in Third World nations to the Scottish context to highlight Scotland’s self-colonisation. Through the lens of Fanon, then, inferiorism is the processes in which the indigenous population comes to internalise the dominant culture or narrative of the coloniser at the expense of their own native, local, traditional culture. For Fanon, to effectively penetrate another culture and to colonise another population’s self-consciousness, their history must be revised to mirror the point of view of the oppressor. On this point, Billy Kay, a renowned advocate of Scottish culture, recalls how the Scots were not taught Scottish history prior to the Act of Union (1707) as this would mean a ‘return of the repressed’ (Robinson 2008). The idea of repressing the events of Scottish history prior to 1707 seems to corroborate Fanon’s idea of inferiorism as this practice has become so entrenched in the Scottish psyche that historian Ash (1980) has talked of the “strange death of Scottish history” and of the Scots being a people without history (Wolf 2010).

In terms of culture, inferiorism as articulated by Fanon was deployed by Beveridge and Turnbull (1989) to express the historical neglect of Scottish culture which led Scots to absorb a sense of natural or spontaneous subordination within the national character. Through the neglect of Scottish history as previously documented not only corresponds with Fanon’s concept of inferiorism but exemplifies Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic violence. By some Scots disregarding their own nation’s history it reinforces the idea of Scots yielding to England by seeing their own history as over and so they never give a thought to making it in their own right again as an independent nation and so they fail to challenge their own alienation.

Perhaps the key areas where cultural inferiority has been established among the Scots is language. Well into the seventieth century Scots remained the established national language and the medium of high and low culture that was distinct from English (Hoffman 1996). Scots in the seventieth century was the language of administration, legal documents, parliamentary records and the royal court with all social classes embracing it without any hint of inferiority (Hoffman 1996).

As England had a Protestant Reformation first in the 1520’s, the 1559 Reformation in Scotland was Scotland falling into cultural line with England and already in the sixteenth century however during the Protestant Reformation, Catholic apologists such as Winzet and Kennedy criticised the Protestant Reformers for importing German theological errors via England and doing so in the medium of the Southern tongue i.e. English. During the seventieth century Scots’ linguistic value began to recede amongst the middle classes who perceived it as tainted and as the language of the less educated working class (Hoffman 1996). In 1561, the Bible was translated into English but, crucially, not in Scots so that Scots lost its prestige, while the Union of Crowns in 1603 saw King James VI of Scotland becoming James I King of England with the court being relocated to London where all royal affairs were now in English (Hoffman 1996).

Crucially, King James’s relocation to London saw the Scottish upper classes follow with the intention of imitating their English peers leaving Scots socially adrift (Hoffman 1996). Through the Scotland Education Act (1872) the English language was promoted with the desire of suppressing Scots as well as Gaelic (Hoffman 1996). Education Scotland (2016) reveals the mistreatment of Scots in education was still evident until the 1980’s as children who spoke Scots could suffer corporal punishment for not speaking English at school.

When viewed through the sociological lens of Bourdieu (1979), such realities evidence how language is crucial for securing cultural subordination and how the notion of ‘linguistic communism’ (where every social actor possesses the right and ability to speak and be heard) is not true in Scotland.

The Scots language corresponds Bourdieu’s concerns as everyone does not have the right to communicate via Scots, as this can place them in opposition to the deemed universal language of English. If we take the term field (Bourdieu 1979) used to describe arenas where social agents operate within and include politics, parliament, patronage, court, and religion which grants legitimacy to the language which Scotland has lost, one player was Sir John Clerk of Penicuik (one of the Scottish negotiators of the Union of 1707) who remarked ‘’the English language … since the Union wou’d always be necessary for a Scotsman in whatever station of life he might be in, but especially in any public character’’ (cited in Balilyn and Morgan 2012, p. 85).

This prophetic comment is epitomised in an incident at an Edinburgh court where a young man was held for contempt of court for answering aye (Scots for yes) instead of using the English form of yes (Crowther and Tett 1999). Similarly, Lord George Robertson remarked “Scotland has no language and culture” (NewsNet Scotland 2014) during the 2014 Referendum; a comment which is a wonderful example of cultural inferiority insofar as it suggests Scotland is void of a recognised culture by its own political elite and representatives. Billy Kay enquired to a Fife headmaster if pupils were encouraged to engage with Scottish Literature and was startled by his response: ‘’No. This is not a very Scottish area” (Robinson 2008, p.5).

Other examples of what seems to be cultural ‘self-hatred’ came when, in response to the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014, Conservative councillor Callum Campbell and Labour Councillor Danny Gibson proposed to have the Scottish Saltire removed from Stirling council’s headquarters and to replace it with the Union Jack (Wings over Scotland 2013). Both councillors said they wanted to see the emblem of ‘our country’ flying from Stirling council’s rooftop, evidencing perhaps the native abandoning their own national identity and culture and embracing that of the coloniser. These councillors allude to Fanon’s theoretical perspective of inferiorism but also to Bourdieu’s idea of symbolic violence whereby Scots not only participate in their own servitude but are the creators of it. The loss of the yes campaign in the Scottish Independence Referendum (2014) can be identified as a contemporary example of the Scottish cringe. The people of Scotland shunned their opportunity to reclaim their liberty the reasons for which are captured in sociological theorist Paulo Freire’s quote ‘’The oppressed, having internalized the image of the oppressor and adopted his guidelines, are fearful of freedom’’ (Freire 2016, p.46).

If you enjoyed this article and would like to support my work. There is a buy me a coffee option via the link below. Where if you would like to you are able to support my writing for the price of a coffee. Any support given wuld be hugely appreciated. It’s becoming more and more difficult to secure any paid writing work. Thanks

https://ko-fi.com/colinburnett46698

My debut novel titled A Working Class State of Mind has been winning many plaudits for it’s social commentary and comedy. The ebook version is currently available on special promo for 99p. Available here A Working Class State of Mind eBook : Burnett, Colin: Amazon.co.uk: Kindle Store

Here are some media reviews of the book

‘’Fabulous book. Colin is a great writer, and the characters are so believable. I couldn’t put it down’’

Janey Godley, Stand-up comedian, Actress, and writer

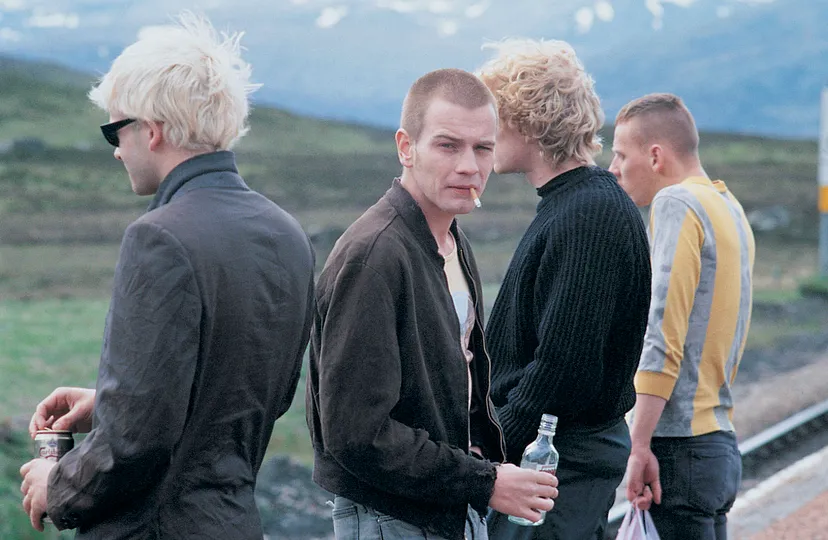

This honest, often gritty account of working-class life is full of dark humour and tales of perseverance through hard times. Fans of Irvine Welsh and James Kelman will enjoy this new and exciting young author.”

— Alasdair Peoples, Visit Scotland

“A glimpse into working-class life in Leith in all its shades and kaleidoscopes. This is Burnett’s first book and he has talent, a rare voice and way with characters which is compelling and at times spellbinding. One to watch for in future.”

— Gerry Hassan, Author and Commentator

“The comic spirit, infused with a Frankie Boyle-like spiky humour, makes them a hoot to read. They also display the fierce class loyalty that distinguishes James Kelman and this gives them an extra punch.”

— Sean Sheehan, Scottish Left Review

“Sharp, witty and thought provoking with undeniable shadows of Welsh and Kelman — Colin Burnett’s debut makes for an incredibly tantalising read.”

— Eilidh Reid, Scots Independent Newspaper

“Finishing A Working Class State of Mind left me looking forward to reading more by Burnett, a strong new voice in Scots and Scottish literature who demands working class voices be heard and read on their own terms. Mair power to his elbow.”

— Erin Farley, Bella Caledonia

“Colin Burnett is an exciting new voice in Scottish fiction — his debut collection of short stories, A Working Class State of Mind, starring Aldo, along with his friends Dougie and Craig, is garnering a lot of attention, and rightly so.”

— Books From Scotland, Part of Our Favourite Things Issue

“Colin Burnett is not only demanding his voice is heard, but that none should be silenced or denied. There is a call for cultural legitimacy which lifts A Working Class State of Mind to another level.”

— Alastair Braidwood, Snack Magazine

“There are obvious influences of Welsh, Kelman and perhaps Warner too in this compelling debut collection, and like these mentors, Burnett brings what feels like lived experience to his writing. His protagonists are full of life in all their frightening brutality, dark humour and ultimate humanity and it is the sheer believability of them and their exploits that places this fresh new voice in Scottish working-class literature at the top of the ever-blossoming tree.”

— Loretta Mulholland, Into The Creative

If you enjoyed this article and would like to support my work. There is a buy me a coffee option via the link below. Where if you would like to you are able to support my writing for the price of a coffee

https://ko-fi.com/colinburnett46698

You can follow Colin on Medium here: Colin Burnett – Medium

Ah gree wi a thing that ye say bit for why did ye nae screive it in Scots? Ye undermine the verra case that ye ettle by screiving in RP English, the leid o cultural, political an economic repression that ye espouse nae tae thole!

Ah’d contend that bi scrievin in Inglis, it mair fully maks the poynt. Here’s a complicatit bit o screivin, an the best wey tae fir it tae be unnerstood bi mony – mibbee even maist – o us is bi daein it in Scots Inglis. It’s unnerlinin how lackin the bulk o us are in oor ability tae comprehend Scots. It micht be the native tongue where ah’m fae but a kin barely scrieve in it a cannae speak it.

At least twa generations afore me didnae hae Scots. An tho ah ken when it comes tae the census maist fowk reckon they use Scots, a fear it’s mair likely they’re at the Scots Inglis end o that leid spectrum.

My my, more ‘gritty’ tales of Leith (other areas of Edinburgh are available); hope they’re a bit better than that nonsense, Guilt, that was recently on the box and was developed in the compost of Leith grit. How about more books, films, treatises about how Leith has changed and continues to change? On my forays there, it seems to be multi-cultural (a good thing) and have a thriving international community.

I don’t have a dog in the fight that constantly presents Leith as ‘gritty’: I grew up in West Pilton.

They call it ‘nostalgia nationalism’, David; a harkening back to often mythical ‘happier’ times and/or historic grudges. Scottish nationalism is haunted by the ghosts of many such myths and grudges, from the ancient wars of independence, through treaties of union, the agricultural clearances, Red Clydeside, and the tragic heroism of the dispossessed lumpenproletariat of the Thatcher age. Indeed, the metapolitics of Scottish nationalism seems to depend on a recurrent narrative of victimisation.

But Colin’s [almost] right. The Scottish Enlightenment did develop ‘the King’s English’ as a unifying institution that went on to become the lingua franca (the establishment language) of the British empire, and that ‘King’s English’ did subsequently inferiorise demotic languages throughout the British Isles, including those in Scotland.

Cheers David, you should check out my novel. Its had brilliant reviews in the media/public. I wanted through my book to show that Edinburgh is just as a working class as any other part of the country. It’s mostly set in Leith but other areas of the toon/midlothian as well. It’s gritty but it’s mostly a dark comedy.

Imperial

Inglis lanwij

What lies behind you?

The deep history and lasting legacy of a culture made by many

Just like any other language in the world

Thing is wae thi inglis fucker

It is a tongue that wants to cut out all the other tongues

A standard brogue indeed.

Good article! It describes well just what has happened to native Scottish language and culture since the Anglo-Saxons arrived in the 7th century. First, however, it is necessary to search online for *Languages of Scotland 1000*. The map which demonstrates the red section will appear before your very eyes!

Now, read this while glimpsing at the map in another window:

“In the late 15th century the best poetry in English came from Scotland. This kingdom, united under Malcolm Canmore in the late 11th century, had four tongues: Highland Gaelic, lowland English, clerkly Latin, and lordly Anglo-Norman French. Since the 7th century, English had been spoken on the east coast from the River Tweed to Edinburgh. Its speakers called the tongue of the Gaels . . . Scottis. A Gael was in Latin Scotus, a name then extended to Lowlanders, who called the northern English they spoke Inglis. After the 14th century, a century of war with England, the Lowlanders called their speech Scottis, and called the Gaelic of the original Scots Ersche, later Erse (Irish).”

Source: A History of English Literature by Michael Alexander, 2007.

And read this as well while bearing in mind the RED section:

“Scots stems from the dialects of English brought to Scotland by settlers in the burghs from the twelfth century onwards. Most of these settlers probably came from eastern England. A contribution was also made by the native speakers of English in the far southeast of Scotland and by settlers from Flanders, for in the twelfth century Flemish and English were still very close. Once ‘Inglis’ (as it was called) had become established in the Scottish kingdom, it went its own way and Scots and English developed on parallel lines, not necessarily borrowing the same words from foreign language nor choosing to abandon or retain the same words from the common inheritance. In many ways Scots appears to be more conservative and to retain more of the speech forms of late Anglo-Saxon than English does…”

Source: (page 331) From Pictland to Alba: 789-1070 by Alex Woolf (The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, 2007)

Maybe it is a good thing that Scots are critical of the mound of toxic patriarchalism, gushing romanticism and fawning to patrons that makes up much of this country’s surviving cultural output. Other countries, like France, USA and England, say, probably have a lot of problems stemming from a failure to reject their own dross. At least we didn’t have to sit through the umpteen McGonigal poems celebrating battles of the British Empire at school. If most Scots believe that their nation’s best cultural endeavours (likely now cocreations with other peoples cross-fertilised with other cultures) lie in the future, not some fake golden age, I count that as a massive plus.

McGonegal is one of the world’s great anti-authoritarian poets. I doubt he knew it, but his works are so insiduous that I would imagine that his verse is still too much for inclusion in general education – radical only goes as far as stuff like tedious concrete poetry: McGonnegal takes the piss out of poetry and it’s authority dictats re ‘bad’ poetry. It is deeply amusing. Not many/any poets caused riots like he did. Certainly not Edwin Morgan.

Nearly missed this!

I agree that McGonagall played the satyr in his writing and, more especially, in the performance of his ‘poetry’. ‘Poet baiting’ was a going concern in later 19th century Scottish theatre; people paid good money to go along to a music hall and throw pelters at walking parodies of the ridiculously self-inflated Victorian poet.

In one of his performances, McGonagall appeared in an elaborate production by representatives of a certain ‘King Theebaw’, who had evidently travelled all the way from ‘Burmah’ to name him ‘Sir Topaz, Knight of the White Elephant’. Numerous memoirs from first-hand witnesses of McGonagall’s act confirm that he was ‘fooling them [his audiences] to the top of his bent’ and that he ‘had an eye to the main chance’; one records how McGonagall had once been spotted ‘leaving a performance with what appeared to be a “satiric smile” sneaking out from the shadow of his egg-spattered cleric’s hat’.

McGonagall, despite his ironic protests of being an impoverished poet, made a decent living out of ‘donning the mask of obliviousness and stupidity’ in order to humorously satirise and thereby subvert the poetry establishment at the time. McGonagall set himself up on stage as the kind of person everyone loves to hate, someone who makes it worth the price of admission for the right to shower him with derisive laughter and rotten vegetables.

McGonagall’s ironic style, with its tongue-in-cheek emphasis on what is precisely not the truth, reappears in much of his material. The beauty of such irony is that it gives his audience the feeling that it is genuinely creating the ‘real’ story of the events he celebrates but whose ‘true’ significance the author himself heroically fails to understand. Hence, McGonagall’s art lies in his ability to speak with two voices: while one voice establishes a naive perspective, usually in praise of some lofty person or object, the other voice cleverly subverts and undermines the surface meanings with ‘unintended’ information. This duplicity is particularly apparent in ‘The Beautiful Moon’. In this poem, in which he apes the sentimental Victorian ‘nature poet’ in his attempts to enumerate each of the moon’s benefits, the ornate diction and innocent sentimentality of such nature poets are undermined by less romantic images of those who use the light to ruthlessly take advantage of the sleeping world: the eskimo who harpoons the fish, the fox that steals the goose, the eagle that devours its prey, the lovers who enjoy the shady groves, and the poacher who poaches.

McGonigall pronounces every aspect of the world around him ‘most beautiful to be seen’ in the same way that Voltaire lampooned Dr Pangloss in his comic novel, Candide. In so doing, he succeeds not only in setting himself up as the humorous victim of his ‘poetry’, but also in embarrassing the many people and objects of he eulogises AND the institution of Victorian eulogy.

The man was a comic genius.

@The Port of Lieth, surely most poetry is so awful as to discredit poetry, but most goes unpublished? There seems to have been a market for William McGonagall’s cheerleading of the crimes of the British Empire during the height of Queen Victoria’s ‘little wars’, in which Highland units made significant contributions. His ode of praise to the victorious invaders in the Battle of Tel el Kebir apparently ends:

“Now since the Egyptian war is at an end,

Let us thank God! Who did send

Sir Garnet Wolseley to crush and kill

Arabi and his rebel army at Kebir hill.”

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45830/the-battle-of-tel-el-kebir

I doubt that many reading the poem in isolation at the time of publication would consider this anti-authoritarian or ironic even by misdesign. Context would have been important. If these battle poems were just mangled regurgitations of newspaper articles, published in the equivalent of today’s Daily Telegraph, their significance would be different from publication in a satirical journal.

Those who have an interest in the Great Man (Occasionally Woman) View of History, unrealistically bigging up Scottish culture to seem critical of Empire, and pumping out propaganda for poetry might wish to project irony and anti-authoritarianism on McGonagall’s works, claiming to see flecks of gold-dust scattered beneath the wax. I don’t. Poets suck up to power because it pays, and they are too cowardly to criticise openly or often even obscurely offend their powerful patrons. Far from risk-takers, poets have the cushioned fallback “Ah didnae mean that!”

‘“Now since the Egyptian war is at an end,

Let us thank God! Who did send

Sir Garnet Wolseley to crush and kill

Arabi and his rebel army at Kebir hill.”

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45830/the-battle-of-tel-el-kebir

‘I doubt that many reading the poem in isolation at the time of publication would consider this anti-authoritarian or ironic even by misdesign.’

No, but the hundreds who flocked to see his performances in Dundee did consider the such ‘poems’ worthy of pelters. It was in that effect that McGonagall’s ironic subversion of the Victorian establishment – his genius as a performer – lay.

But I agree that the ‘Great Man’ theory of history – the so-called ‘Scottish Idea’ – which was first propounded by Thomas Carlyle (and which McGonagall’s ‘poetry’ also mocks in its exercrable eulogising of the likes of Queen Victoria and Viscount Wolseley, one of the most prominent and decorated war heroes of the British Empire during the era of New Imperialism) is flawed.

When the theory was first popularised, one of its most prominent critics was biologist and sociologist, Herbert Spencer. Spencer held that attributing historical successes to individual decisions was primitive and unscientific, and that the so-called ‘great men’ were solely products of their social environment. Before a ‘great man’ could shape and build his society, the same society had to structurally shape and build him. Marx made much the same criticism.

There is also what is sometimes called ‘survivorship’ bias attached to the Great Man theory. When the theory was first popularized, one of the most prominent critics was biologist and sociologist Herbert Spencer. Spencer held that attributing historical successes to individual decisions was primitive and unscientific, and that the so-called “great men” were solely products of their social environment. Before a “great man” could shape and build his society, the same society had to shape and build him.

Survivorship bias also attaches to the Great Man theory of history. Survivorship bias is a type of sample selection bias that occurs when a researcher mistakes a visibly successful subgroup of a population as the entire group. The Scottish idea excludes those who may not have necessarily been heroes, but without whom history would not exist as we know it. Carlyle’s concept thus raises a philosophical concern about the functional role of the individual versus the deeper structural role of the collective in human history.

Aside from the logical aspects of the Great Man theory, Carlyle has also been criticised for the way his essays ‘On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History’ were written (e.g. in Bert Spector’s essay on ‘Carlyle, Freud, and the Great Man Theory’). The use of ‘man’ itself in Carlyle’s writing reflects a gender bias: a perception that history lies on the backs of dominant males, combined with conviction that leadership is inherently masculine. But there is also a deep religiosity to Carlyle’s language, especially in his warning that, for those of us who are not divinely appointed by God to become heroes (one of the Calvinist ‘Elect’), our jobs are to recognise and uplift ‘great men’ into their positions of prominence. Only by obeying the rulings of these leaders can the ‘sick’ be healed, according to Carlyle. (Don’t forget that one of Carlyle’s archetypical ‘great men’ of history was John Knox, another was Mohammad, another still was Oliver Cromwell, all of whom exuded the Scottish Tory sense of predestination or moral determinism or exceptionalism of the sort that James Hogg anonymously lampooned in his ‘Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner’ earlier in the century).

The Scottish idea may ultimately say more about the patriarchal and individualistic assumptions (or deep structure) of Western society in the 19th century than it does about the great men who, Carlyle supposed, individually progress of human history. It demonstrates how historians and other scientists reflect the prejudices of their age in their work.