Remembering and understanding our recent history: 2014 and all that

The 2014 indyref was an immense moment in recent Scottish history. We are still understanding, remembering and coming to terms with its ongoing impact of – both in Scotland and in how it has shifted the UK.

The 2014 indyref was an immense moment in recent Scottish history. We are still understanding, remembering and coming to terms with its ongoing impact of – both in Scotland and in how it has shifted the UK.

2014 was both a ‘Big Bang’ and a catalyst that can be seen as part of two bigger stories. The first was about the kind of Scotland we want to live in; the changing nature of authority and power in Scotland, and the long-term decline of the hold of the liberal unionist establishment. The second was about Scotland’s place in the union that is the UK – and its relationship with that union and its politics.

These ambitious and far-reaching issues that had influence before and beyond the independence debate fed into 2014 – and still affect and shape current debates and future possibilities.

Despite all of this, large parts of Scotland have not risen to the challenge of trying to understand 2014 and why it happened; to explore the forces that were in play and why it tapped such powerful democratic impulses – and where that leaves us collectively. That was true in the 2014 long campaign and in much of institutional Scotland like the BBC and STV. And it is true of significant sections of society since 2014 – including some of the groups which had difficulty in the referendum, and others such as the SNP and academia. The latter has failed to produce a single comprehensive study of the campaign and its impact (when such studies were undertaken of our two previous Scottish-only votes in 1979 and 1997).

Imagining the Scotland we live in and 2014

This absence is true of the world of arts and culture post-2014 – a paradoxical situation considering the engagement of the arts and cultural community in the run-up to 2014. Wider drivers do though need to be taken into account including the decline of political theatre after a golden era in the 1970s and 1980s which contributed to the rise of cultural self-determination; the passing of the theatre companies which pioneered this such as 7:84 and Communicado Theatre; the changing of the guard generationally from the writers and cultural innovators who contributed to the making of modern Scotland; and the current climate of artistic conservatism in publicly funded arts which is reinforced by cuts and constraints to arts funding (with a contemporary controversy ongoing about Scottish Government funding).

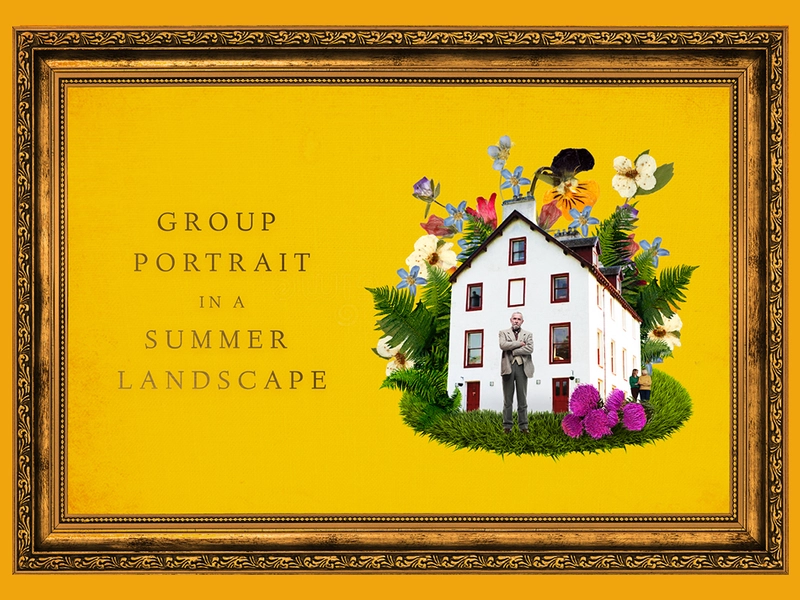

It is heart-warming then that one significant attempt to address this is Group Portrait in a Summer Landscape, written by Peter Arnott and directed by David Greig. A partnership between Pitlochry Festival Theatre and Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum Theatre, this opened in the former last week and shifts this week to the latter.

Arnott and Greig present this as a seminal work about 2014 and beyond, Greig describing it as ‘a big new Scottish play that thinks about our time’, while Arnott reflects that ‘it allows you to see the referendum as one moment among all the other moments’ and as one chapter in an ongoing Scottish story: politically, culturally, generationally and globally.

Group Portrait has a sense of place and location, set in a Perthshire country house one weekend before 2014’s big moment of decision. Eight characters come together at the behest of Rennie, a left-wing academic who is voting Yes and has called family and friends together as he ruminates about some of the big life decisions he has to face.

There is lots to admire about this play. Its staging, acting, ambition, intentions, and clever use of music as drama beyond the obvious. But there are significant limitations. These eight characters, plus another who appears intermittently, leads to an often-crowded stage and little space to get to know most of them. We get sketches and outlines of some, and inexplicably in one or two cases, too much background information (for example about one character’s career in TV and film) which doesn’t add anything.

The first act offers promise with the 2014 referendum put in a broader landscape. But the political dialogue never really rises above the superficial and soundbites, offering little more insight and depth. Hence, we hear what are by now well-worn lines about ‘Labour losing its way’; ‘the British road to socialism’ being dead; the nature of the British state and government; the character and limitations of Scottish nationalism; the disappointment of Blair and Brown and tipping point of the death of John Smith; while 1979 and 1997, Scotland’s two previous stand-alone referendums are referenced in passing.

This could have been a foundation for exploring something but in the second act 2014 disappears into the background in a set of exchanges dominated by observations about the big challenges of modern life. Hence, we get comments and exchanges on climate change, the crises of Western society and liberalism, the decline of religion and meaning of morality after God.

One of the figures, Charlie, now a successful TV presenter, whose role is to burst the bubbles of conceit and self-congratulation of liberal opinion and be a bellwether for the forces of populism and anger raging across the planet, launches into an impassioned, lengthy soliloquy. He challenges the hypocrisies of left-liberal smugness, warns about the coming political storms and new age of barbarism which he thinks it will entail – all of which feels forced and risible from someone who never rises above the one-dimensional.

An unintended consequence of a play which aspires to be making sense of 2014 is to cause us to reflect and look at what this means for us as individuals, collectively, and as a society and nation. Time and everything that has happened since (Brexit, Trump, COVID, Ukraine) provide an opportunity to see 2014 not just in retrospect, but in relation to a host of other developments and landscape beyond the Scottish question.

Is Scottish independence the big question we think it is?

Group Portrait poses, whether deliberately or by accident, an element of reflection on the relationship of Scotland and our deliberations on big global questions. Is Scottish independence as major and defining an issue as many people thought in 2014? Does it pale into significance compared to some of the major existential questions? Is it possible to consider as many did in 2014 that a nation with a population of five million people can aspire and affect change on a global stage? Or are we kidding ourselves in this: our very own Scottish version of the Great British powerism and boosterism which so plagues UK politics and drove Brexit?

Group Portrait is not really a play about 2014. Instead, it uses 2014 as a backdrop to flag up a host of elemental questions and observations about what it is to be human and an engaged citizen of the world. And in this its aspiration and reach is stretched over what is ultimately too wide a canvas. Nine characters are too many to know in any great detail and intimacy, while several appear as caricatures – one in particular as a pantomime villain.

This is not intended to sound unduly negative. It is surely better to dare to dream, imagine and convey some of the powerful and democratic impulses which have informed Scotland in recent years, and which brought about the 2014 indyref, and are still with us in the present. Telling such stories and daring to give voice to the emotions, hopes, fears and arguments around 2014 and do so in a longer lens is laudable and commendable, and Arnott and Greig are to be commended for their attempt.

Group Portrait carries a weight of expectations which have become heavier because of the absence of a conscious political theatre engaging with issues raised since 2014. Maybe that is a contributory factor in why in many respects it felt transitory and tentative, and not adding much to our understanding of that pivotal moment in history.

There will in future years be many more attempts to understand 2014 and how Scotland sees itself and its place in the world. Dramatists, artists, musicians; academia from politics to sociology and history, and broadcast media will ask questions and explore issues which they have not shied away from in the past, but have done so since 2014.

Understanding 2014 entails respecting and reflecting upon that debate as part of a longer story which is not just about independence. One which also recognises the deep forces reinforcing and underpinning the conservative imagination and status quo in Scotland which does not really want to have a generous, broad-based conversation about our collective future and how we best determine that. That story is still being written and has still to be fully explored, and in this respect, Group Portrait is a brave, but flawed attempt to contribute to this and our understanding of ourselves.

Group Portrait in a Summer Landscape was at Pitlochry Festival Theatre and is on at the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh, from 4-14 October.

I’d take a slightly different approach to reading Peter Arnott’s play.

In the context of MacDiamidean ‘World Culture’, everything one reads, whether its a piece of political theatre by a Scottish playright or a collage by a Malawian artist or a track by a Dutch musician, should make one reflect on one’s own identity and what it means to be a human being, and everything one makes should be an expression of that identity. Perhaps, then, reading it from that perspective, the shortcomings that Gerry detects in Arnott’s play reflect not so much a failure on the part of the artist himself to read contemporary Scotland correctly than an accurate expression of a national identity that seldom ‘rises above the superficial and soundbites’.

MacDiarmid reckoned that ‘the Scots genius’ (that which would make us distinctively ‘Scottish’ rather than the parody with which Tory nationalism of ‘Scots Wha Hae’, the romantic Jacobites and home internationals had colonised us) wasn’t to be found in some mythical past that the b*st*rd*n English had ‘cancelled’, but was something that has not yet existed except as a latency or potential that’s yet to be realised. His ‘Scottish Renaissance’ (a Scottish version of modernism) was a project intended to realise that ‘Scots genius’.

What’s salient here is that the artists of the Scottish Renaissance project looked not to Scotland’s vitiated indigenous culture but to ‘World Culture’ as the womb from which the Scots genius would be born. (This is way lay at the heart of MacDiarmid’s quarrel with the Scottish folk revival, which he saw as a reactionary ‘dead-end’ for Scottish culture.) Perhaps what we should take from Group Portrait in a Summer Landscape is that contemporary Scotland still has a vacuum at its heart, beneath ‘the superficial and soundbites’, and that, in our self-creative ‘making’, we still need to look outside ourselves, to a ‘World Culture’, to fill.

The 2014 indyref was an immense moment is recent Scottish history’.

It is possible that history will judge the referendum as far less significant than that. After the 2014 vote it appeared that Scotland was certain to become independent, with only the timing to be finalized. Nine years on, things look rather different.

The failure of the SNP – as demonstrated in yesterday’s by election result – may doom the whole enterprise.

Until recently I had thought that the path of the last half century, three steps forward, followed by one or two steps back, would probably lead to

independence. Now, I am less convinced.

Nicola Sturgeon’s departure has shown how lacking in political talent the independence movement is. The prospect is that this inadequacy will get worse. The present leadership may fail to instil confidence but a future leadership of Mhairi Black, Ross Greer and Kirsty Blackman could be

noticeably worse.

Anyone who doubts how catastrophic bad leadership is for an organization would do well to talk to a few Manchester United or Rangers supporters.

And then there is the question of intellectual talent. That is for another day.

Right now it would be hard to make a compelling case that Westminster politicians are more able, intellectuallly gifted, or astute on policy than their Scottish counterparts. And it would take a singular kind of nostalgia to conclude that Scotland is able to access less Ministerial talent today than it could in the halcyon days of Joseph Westwood, Sir Hector Munro, or Danny Alexander. Talent waxes and wanes in all polities, and always will.

Although, as I keep saying, florian, the state of the nation isn’t a moral issue (to do with the calibre of people involved) but a structural issue (to do with how power is exercised in the realm of our public affairs). The moral qualities or ‘competency’ of our politicians and our civil servants is a distraction from the more profound and growing dysfunctionality of our political institutions. That’s maybe what Peter’s play misses.