What on Earth are you doing here?

As ever, Richard Demarco challenged his audience. Even in a warm, enclosed venue, he offered bracing re-iterations of many of his familiar themes – all delivered with gusto and passion. At root, the focus was the fate of the Edinburgh Festival – Demarco is clear that the Festival and Fringe have lost their way and have reached a crisis point. But when and why?

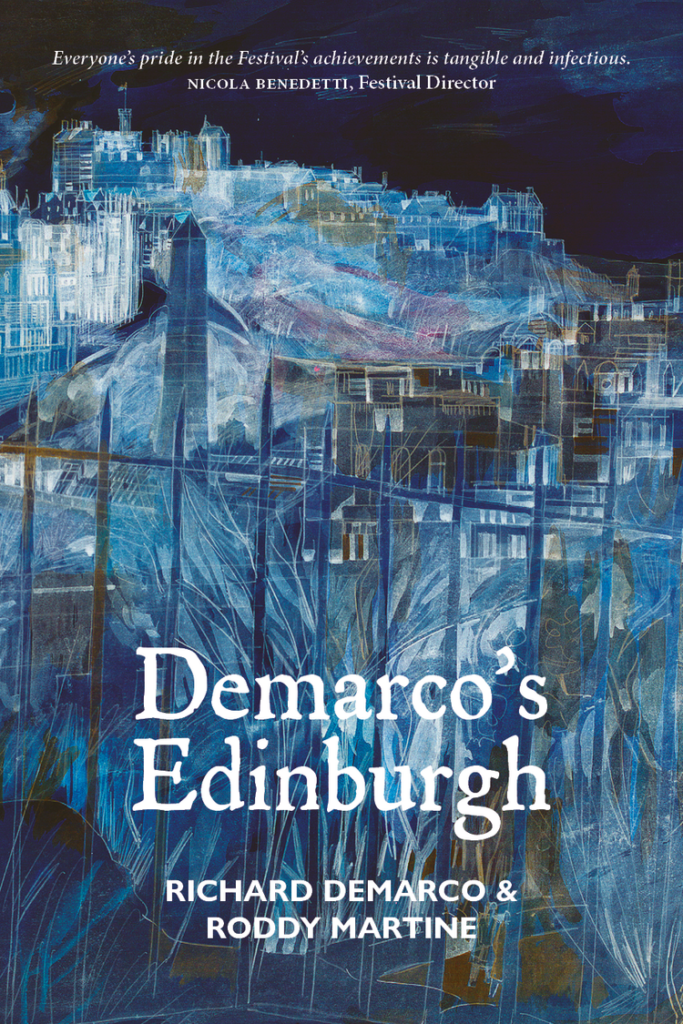

Demarco was speaking alongside the author and journalist Roddy Martine at an event (on November 6th) at the Royal Scots Club to discuss their book Demarco’s Edinburgh – published this summer by Luath. The event took place in the subterranean Hepburn Room, with the journalist Jackie McGlone in the chair. She had the near impossible task of keeping Demarco from heading down one of his many, admittedly fascinating, tangents. She did better than most! While there is a scattergun character to many of Demarco’s public appearances, underneath the public persona as a hyperbolic showman there lies a unique and challenging cultural vision.

McGlone introduced Demarco by using some of the descriptions that have been used to try and sum him up over his 93 years: beloved legend, talkative dynamo, age old scrounger, life enhancer, controversial ball of energy. All of these are simplifications but all have a grain of truth.

Martine was introduced as a renowned journalist, the author of 30 books, and all-round ‘man about town’. One of his books is, appropriately, a history of the Royal Scots Club (Not For Glory Nor Riches). Martine was given the task by Luath Press to put together the book in about three months. Somehow, the book emerged in time for the Festival – just.

Opening eyes

The book charts the two men’s relationship with the Edinburgh Festival and the way it has comprehensively shaped their lives. For Martine, it was his entry point into journalism, allowing him access to meet a variety of cultural legends. While working for an Edinburgh Academy school magazine he had his first major scoop – getting an interview with David Frost. It taught him that with “enough brass neck, no doors are closed to you”. For Martine, the way that the Festival had changed his life was emblematic of the way it changed Edinburgh as a city. These “magical” figures had brought light to a “dark, gloomy city” (the Edinburgh captured in The Battle of the Sexes, the 1959 British black and white comedy film with Peter Sellers, Robert Morley, and Constance Cummings).

Martine believed that Demarco had played a leading role in making Edinburgh a far less dour place. The Demarco Gallery (when on Melville Place) was the place, “a magnet for bohemian types” and helped form a city that was no longer “prim and proper”. Going there “opened my eyes”. In an aside, he mentioned that among the bizarre and wonderful collection of people he saw at the Demarco Gallery was Moshe Dayan (then Minister of Defence of Israel), wearing his trademark eye-patch.

Demarco related that Edinburgh of 1947 was still reeling from war – “the biggest disaster to hit the human race”. Food and electricity rationing was still in place (“even light was rationed!”), and there was no proper accommodation for the performers and visitors; residents were asked to help out. Prior to the festival the city had “no colour” – its narrow, enclosed character typified by “frosted glass on the windows of pubs”. It was “not a happy place”.

For Demarco, the ‘Festival spirit’ had a strongly European dimension, connecting performers from across the war-torn continent. In 1947, as a Holy Cross Academy pupil, Demarco was exposed to the best art and culture from continental Europe, as well as the UK. It made him recognize that “I was living in Europe not the British Empire”.

The performances that Demarco witnessed in that first festival have stayed with Demarco, leaving behind a clear imprint. These included the theatre of Moliere and the songs sung by the Yorkshire lass with “the voice of an angel”, Kathleen Ferrier. Ferrier’s performance was conducted by Bruno Walter, who had escaped Nazi Germany in 1933. Walter’s participation embodied the unifying aspect of culture.

Through their performances, Demarco had been introduced to the “language of the arts”, one which transcends national borders and draws people together. Demarco also has vivid memories of a school trip, organised by the Holy Cross Headmaster, to Paris, where he saw performances which left him “in tears”. The ballet company he saw subsequently performed at the Empire Palace Theatre (now Edinburgh Festival Theatre). These cross-national connections and cultural pollinations were much needed in 1947 with much of Europe in ruins and with those in countries in Eastern Europe being imprisoned by Stalinism. Cultural dialogues with those trapped behind the Iron Curtain (such as Marina Abramović) became a major aspect of Demarco’s life.

A money making machine

When describing the glories of the Festival and Fringe, Demarco tends to use the past tense. He sees the decline of the Festival as a symptom of something deeper. Edinburgh had forged a position as the “world capital of culture” but could no longer lay claim to this. Both Demarco and Martine believe that the rot sent in in the 1980s and 1990s, when the Fringe became increasingly dominated by stand-up comedy and became a “money making machine”. This was at odds with the original mission of the Festival which was about ‘the flowering of the human spirit’ – that was its raison d’etre. There was a strong streak of pessimism throughout Demarco’s comments, and a sense of terminal decline. Since the 1990s, Demarco alleges, the festival has been hit by a “tidal wave of mediocrity”. Art was “a sublime thing…not to be reduced to a marketplace”.

In critiquing the impact of mammon on the cultural world, Demarco places himself within a recognisable strand of thinking. What Alan Sinfield terms the ‘left culturalists’: such as Richard Hoggart, Dennis Potter, Alan Bennett, Melvyn Bragg. They saw the great cultural institutions (such as the BBC and the Arts Council) as a bulwark against commercialisation and a force for cultural democratisation. In contrast, Demarco has little faith in Scotland’s cultural institutions, especially what he dubs “Uncreative Scotland” (he did not demur when one of the audience members – David Black – used the term ‘Cremated Scotland’). As a result of falling out with many Scottish cultural institutions (including the National Galleries), Demarco has relied on the support of his cultural allies (some of whom were in the room), as well as private patrons. Without strong institutional support has left him in an uncertain position. “What do I do with all the memories?” – those that are held in his vast archive, much of which is currently at Summerhall.

Europe or America?

A repeated theme of Demarco’s remarks was a concern about the Americanisation of the UK. Lying behind this is the idea that the UK is at the centre of three concentric circles: Europe, America, and Empire/ Commonwealth, and its connections to these three entities shifts over time. This is a theme explored in works such as Andrew Gamble’s Between Europe and America. For Demarco, it is the connections with Europe that should be celebrated and strengthened. Having visited America in 1959, he found that he “didn’t like the American way of life” and was unimpressed by their cultural institutions.

He believed that Edinburgh “remains recognisably European”, though some recent developments (such as the glass towers at Haymarket – ‘set to become the highest profile mixed-use development in Scotland’) have stated to erode this. There were people who “are destroying Edinburgh”. Developments at the Leith Waterfront and the Cammo Estate were creating something alien: “many of the streets are not Edinburgh”. Demarco exclaimed that “we could end up looking like Toronto or San Francisco!”. Edinburgh was fundamentally a historic city and this was something to be cherished. The architecture in areas such as the New Town (where the event was taking place) was a manifestation of higher values, deriving from the Enlightenment. For Demarco, the Festival represented a reawakening of such values; so its decline is particularly serious, with ramifications beyond the cultural sphere.

Out of darkness

As he reiterated, the Festival itself was born out of horrific human catastrophe (the Second World War). That the world was facing a series of dire threats – conflict (Ukraine, Israel Palestine), threats to liberal democracy (Hungary, Italy, even the USA,) and climate change. Perhaps something positive can emerge out of this. This is a theme articulated by David Runciman in a recent talk at Edinburgh University. He made the slightly depressing point that major social and political change often only comes following conflict. For example the birth of the welfare state in the immediate post – war era. The birth of the Festival grew out of a similar desire to heal wounds. More fundamentally, it was “born out of hopelessness”.

Roddy Martine, was more optimistic. Having recently interviewed her, he saw in Nicola Benedetti (the current Festival Director) someone with the strength and cultural connections to make a genuine impact and perhaps help return the Festival to its original mission. He felt that one thing that would help would be for her to meet her fellow ‘italo-scozzesi’, Demarco. Those in the audience will attest to the impact spending time with the Demarco has; how it can inspire.

As with many of Demarco’s public appearances, the event had a communal feel, with audience members chipping in with their reminiscences and questions. This connects this to Demarco’s dislike of formal galleries and theatres: he wanted to see much greater interaction between the audience and the artists. Events such as theatre performances at the Forrest Hill Poor House manifested this, with audience members playing a part in the plays by the likes of Tadeusz Kantor.

Demarco has a participatory view of culture. What he urged people to do was become ‘makers’ or, to use the Scots term for a creative artist, a Makar. In short, not merely to be a consumer of goods and culture but to play an active role. Art should be something engaged with all your life. Those in later life should continue to do so, not spend their days watching TV in a care home, in a state of passivity.

Fighting for existence

In defending the original values of the Festival, Demarco sees himself as “fighting for our existence…what we present to future generations, if there are any’. In talking in an existential manner, Demarco draws parallels with the ‘culture warriors’ of the hard right, such as the late Roger Scruton. However, Demarco’s promotion of the avant garde places him in another category. Further, while followers of Scruton laud Orban’s Hungary, Demarco would see him as one of the figures threatening liberal democracy in Europe. In addition, the hard right tends to dismiss the threat of climate change as overblown. A figure such as Demarco reminds us to avoid easy classification. Echoing something is not the same as sharing the same worldview. Ideologically, Demarco is not easy to pin down. That’s to his credit.

Demarco ended by proclaiming that he’d devote his remaining time to reviving the “True spirit of the Festival” – “I’ll be fighting till my final breath to promote the language of the arts”.

What keeps him motivated is a deep sense of things as yet incomplete. “I’ve still got work to do”. This, despite his many books, films etc and , by his own estimation, direct involvement with about 2,500 exhibitions and 2,000 theatre performances.

His challenge (“What on Earth are you doing here?”) was to provoke his audience into actively promoting the language of the arts through their work and deeds – not just sitting in the audience nodding along.

I love the book cover and this article set so many thoughts racing. I remember an exhibition at Summerhall in 2015 of Demarco’s archive. There was little in the way of stunning pieces, but an interesting cumulative impact from much ephemera he had made or collected. It said more than many more explicit exhibitions I’ve seen. If he can stimulate a change in attitudes to the International Festival (which has been subsumed by the Fringe for many commentators outwith Edinburgh) that would be wonderful. I wish I’d been at the talk !