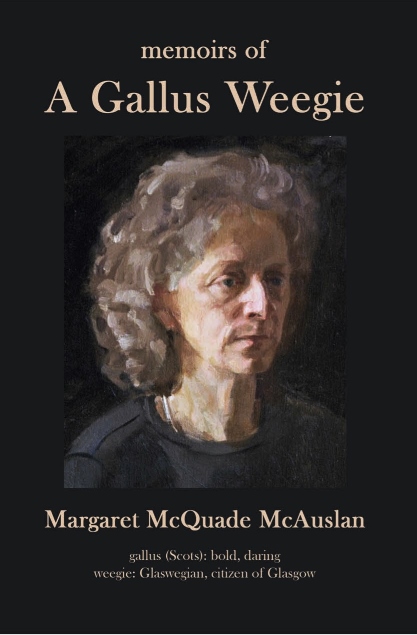

Memoirs of a Gallus Weegie

Memoirs of a Gallus Weegie by Margaret McQuade McAuslan reviewed by Jim Ferguson.

This is an impressive and expansive book of memoirs. It is ambitious, honest, bravely revealing, heartfelt, funny and deeply emotional. On reading Memoirs of a Gallus Weegie I was reminded of the prose work of such writers as Pablo Neruda, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, William Carlos Williams and Sylvia Plath: the two writers out of these that my thoughts drifted to most frequently were Neruda and Hurston. Neruda completed his Memoirs in 1973 just a few days after Salvador Allende was violently removed from power by Chile’s right-wing politicians and military establishment. Neruda’s Memoirs are clear-eyed, opinionated and matter of fact, as are McAuslan’s. Neruda wrote of his own poetry collection Estravagario “For my taste, it’s a terrific book, with the tang of salt that the truth always has.” And I can only say that I feel the same way about Memoirs of a Gallus Weegie.

Zora Neale Hurston’s autobiographical prose tells of her difficulty in earning money as a black woman writer in the USA of the 1930s and 40s. Financial concerns are very acute in the role they play in holding back working-class writers and artists throughout the world and throughout history, particularly since the time of the Industrial Revolution. And such concerns – simply putting food on the table – arise on several occasions in Ms McAuslan’s memoirs. Nevertheless, in McAuslan’s narrative, the old ‘Scottish Arts Council’ comes out as more supportive and engaged with grass roots writing than the institutions that have now taken its place in the Scotland of 2023.

McAuslan’s memoirs cover the period from 1953 to 2023. The book might just as well have been titled an autobiography rather than a memoir, but I’m guessing the author opted for the title of memoir because of the tough choices she faced in deciding what to include and what to leave out. On page 316 she writes about a women’s history project she was involved with: “But I had structured the project in such a way as to ease them in gently. Each session covered a different period of life, beginning with early childhood, school, teenage years, sex and relationships, work, marriage, motherhood, family problems, ageing, menopause, older age, and health issues.” This listing of the structure of the project could easily be applied to the Memoirs themselves, which are for most part presented in chronological order, with the odd digression here and there giving clarity and depth.

The evocations of Glasgow in 1950s and 60s are outstanding. Post-war Glasgow is shown in all its poverty, community resilience, sectarian stupidity, and generosity in clear and engaging sentences. Early in the book we meet Margaret’s mother and father, and her four brothers Stuart, Billy, Scott and Charles. In addition to these central characters, we hear of numerous friends, extended family, teachers, and the family GP Dr Winicour: “It is difficult to convey to younger people who have been raised in a less communal environment, just how vital it was to be a part of the close-knit community in The Calton, or any other working-class community in the city. We lived at the London Road end of Claythorn Street with Great Auntie Jeannie living in the tenement along from us. Her daughter, Jean Foy, my father’s cousin, lived with her family round the corner on Stevenson Street. My mother’s Uncle Bobby and his family were just along the same road, at the Abercromby Street end…. …Family members were close at hand, neighbours helped each other out with child-minding, small loans of money or food, or odd jobs for people who could not afford to hire a company.”

McAuslan was an intelligent and somewhat rebellious child who went to Primary School in The Calton and Secondary School in Castlemilk, having been moved to the latter in the controversial ‘slum clearances’ of the 1960s. Disgusted with the Orange Lodge and religious hypocrisy(,) she was a devout atheist by the age of fourteen. Influenced to some extent by her older brother Billy she was adopting socialist politics around the same time: “We had been in the Young Socialists since 1967 and were very critical of the class divisions that we were confronted with at every turn. Most of our teachers, especially the older women, were from the middle-class. Many of those women were spinsters and some students made fun of them for that. We were too young to understand that a whole generation of women had lost their sweethearts in the Second World War.”

A further, somewhat ironic, reason for her adoption of socialist politics was the poverty she witnessed while in New York 1964: “I was startled when I saw a black man without legs hurtling along the sidewalk on a wooden bogey, using his gloved hands to propel himself. I asked my Uncle Charlie why the man did not have a wheelchair and he simply said, ‘Because he’s poor.’ …I was baffled.” One can imagine that such a sight of poverty amongst the affluence of New York City might stay with a young person and it clearly stuck with Margaret.

There were cultural and economic reasons that made one rebellious and it is easy to understand how she became both a socialist and a feminist: “From the age of 12, puberty hit and I had my first menstrual cycle. With no older sisters to learn from, I was totally unprepared for this. Even my relatively progressive mother was unable to broach the subject of sexuality, such was the Calvinistic attitude at the time. My hormones were all over the place and I was deeply unhappy as my strange, adolescent body pushed me from childhood into an ungainly, big-breasted teenager that I did not want to be. Everything was changing more rapidly than I could cope with. I had always had good friendships with boys but now there was this sexual element that formed a barrier between me and my male peers.”

These struggles to tear down barriers might lie behind McAuslan’s love of travel and genuine interest in, and curiosity about, other cultures that would affect the trajectory of her future. On leaving Glenwood High School in the early summer of 1970 she went on a short tour of Europe organised by the school, but she did not return to Scotland. Instead, she stopped off in London for about two months, taking a job as a filing clerk and staying with friends in cramped accommodation. She used cash saved from her wages to finance a flight to New York and spend time with her maternal grandmother. Other family members including her bother Stuart and mum and dad were there already for a wedding. Her father apparently was not too pleased about her choice of wedding attire. Those were the days. However, on arrival “That first night I went out with Stuart and cousins Gregor and Christine… I had my first smoke of marijuana. It was Monday. Within four days I was to experience weed and speed, was offered glue, and had my first acid trip. Welcome to Brooklyn.”

Glue was not to her to taste but she appears to have enjoyed the hash and LSD. McAuslan’s attitude to drugs is one of live and let live. Human beings have used mind altering substances for centuries, millennia even, why criminalise people for taking one mind altering drug rather than another? It seems to this reader that McAuslan’s commitment to equality is what has motivated her in many aspects of her life, including her role as a poet and artistic organiser.

After an eye-opening six months or more in New York she returned briefly to Glasgow and waitressing work before embarking on the journey described in the chapter titled “Glasgow to Beirut”. This chapter is a joy to read and where we see McAuslan truly make the transition into adulthood. It is the summer of 1971 and she is eighteen years old. She is a sensitive, intelligent explorer going out into the world to see what’s there. Not overly self-confident but nobody’s fool. From this point forward the book flies along at a brisk pace and there is still so much to tell. So much pain and grief, so many happy moments, smiles to be smiled and tears to be shed.

In addition to a commitment to equality there is also contained here a desire to escape from the industrial poverty that has haunted Glasgow for decades. Most human beings with any degree of feeling are aware that poverty is lethal. And that it does not come alone: it leaves people vulnerable to addiction and mental illness, to both victimhood and the easier perpetration of the most heinous crimes. In having a strong and loving family and a half decent network of friends and acquaintances one can perhaps ward off the worst these. Decent education can help. But one cannot do these things alone, it is necessary to have help and support. And McAuslan’s memoir is representative of the need for such social solidarity. Nevertheless, money by itself is not enough, compassion and caring are necessary too.

In 1972 McAuslan moved in with Michael Murray: “Michael and I were to spend the next 20 years together and had our son, Ciaron, in 1973. I once loved him deeply and, although we have been divorced for over 30 years now, we remain friends. Our relationship encountered numerous emotional traumas, emanating from my family’s circumstances for the most part, though some other issues also came into play. Whatever, in the long run we were unable to ride out those storms.” At that time she had taken a job in a homeless hostel working with “women fleeing violence and families who had fallen on hard times.” Unable to secure decent accommodation in Glasgow they decided to try London and after some similar accommodation problems in Shepherd’s Bush they ended up moving into a Scientology community at “Saint Hill, just outside East Grinstead… …What can I say about Scientology? One fucked up cult that messes with peoples’ heads and destroys lives. That sums it up.”

McAuslan has an interesting inside knowledge of Scientology all of which is fascinating reading. Once Margaret, Michael and Ciaron had escaped from the Scientologists they returned to Scotland and lived a fairly conventional life. If anyone’s life can be described as conventional.

In 1988 her father died and she wrote:

Epitaph for my father, Willian Foster McAuslan, 1922-88

would he have us weep?

released from the agonies of a diseased body

and the hopeless frustration of a caged mind

he has found an end to suffering

and for those of us for whom his pain

had become a blade

tearing our very hearts until

all strength and courage drained

we could bear no more

there is relief of sorts

so, when remembering him

think not of wasted flesh

the sunken eyes and

silent pleas for help

much rather think upon

the reckless youth he once was

his generous spirit

the way he made you laugh

and those precious

private moments when

as father, brother, lover or friend

he gave you his best

and be glad, be glad

for he is at rest

This is one example of the poetry that is peppered throughout the book. All of the poems are direct and succinct, they add an extra dimension to the prose and show much of the spirit of McAuslan’s personality.

A spine of grief and the fortitude of resilience required to live through it take a central place in McAuslan’s Memoirs. One of the most impressive sections is the story of the life and death of Edinburgh poet Sandie Craigie. It is deeply moving. Sandie was a great poet and such a wonderful person: it was difficult not to like her. This book does so many things on so many levels. It is history, adventure, open and welcoming, harrowing, but above all moving. McAuslan’s writing on Sandie Craigie is sensitive and outstanding. It brought tears to my eyes and a lump to my heart. If you have only vaguest interest in Scotland’s poetry and art this book will give you an education and a thrilling adventure. It is a journey through a life lived with clarity and determination, a great achievement, and a wonderful read.

Zora Neale Hurston wrote in Dust Tracks on a Road: “If writers were too wise, perhaps no books would be written at all. It might be better to ask yourself ‘Why?’ afterwards than before. Anyway, the force from somewhere in Space which commands you to write in the first place, gives you no choice. You take up your pen when you are told, and write what is commanded. There is no agony like bearing an untold story inside you.” It is a tremendous pleasure to read what Margaret McQuade McAuslan has written in response to that “force from somewhere in Space”.

Margaret McQuade McAuslan is now resident in Ivancha, Bulgaria. Her book is available via Paypal or Bank Transfer from: [email protected] Glasgow Women’s Library Shop, and Locavore, Victoria Rd, Glasgow

Dear Margaret, old friend, your book sounds wonderful.

Hey Paul, a lot of water under the bridge since we last communicated. Very surprised to see you comment here. Buy the book, learn a lot about me that you never knew in those days gone by.