Radical Scotland: Making connections and the case for Scottish self-government in Thatcher’s time

Radical Scotland: Making connections and the case for Scottish self-government in Thatcher’s time by Douglas Robertson and James Smyth (1)

Part One: We need a new direction

This article is published ahead of the major conference The Break Up Of Britain | A conference salute to Tom Nairn celebrating the life and work of Tom Nairn and as a reflection on where we are today.

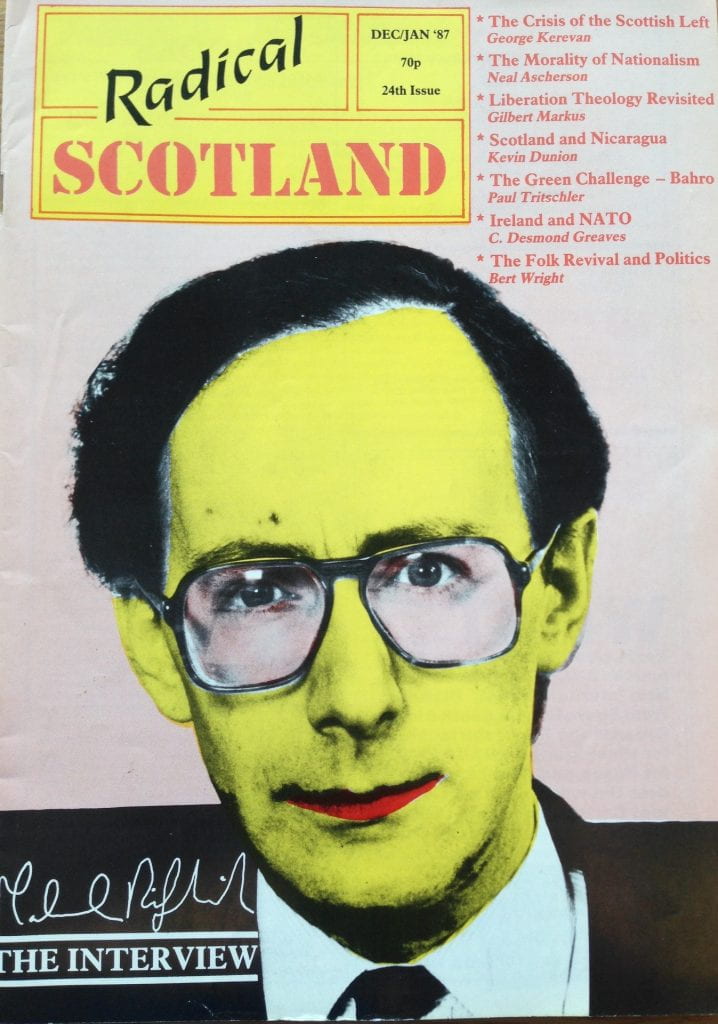

Forty years back, the bi-monthly magazine Radical Scotland made its appearance. A decade later it made a conscious decision to close taking the bold, perhaps even arrogant, view that with the groundwork for the Scottish Parliament completed, its work was done. It published during a very bleak time for Scottish politics, a time when Thatcher was in the ascendency and hopes of a Scottish Parliament had been all but extinguished. But equally this was also a very creative and hopeful time that allowed new ideas and ways of thinking to challenge that political landscape. Given the time now elapsed, it now seems opportune to consider Radical Scotland’s contribution to bringing about that seismic shift to both Scottish and UK politics.

Reflection demands that we authors be up front about the various influences acting upon our particular understanding and interpretation of those events. Our backgrounds are similar, yet also quite different. These differences are that one is east, while the other west coast, which still represents a significant social division within Scotland; one of us was Catholic, the other Presbyterian by upbringing, though neither was practising; one was brought up in a large council housing scheme, the other in a suburban bungalow; and in relation to party politics, one was a Labour Party supporter, the other was a Scottish National Party (SNP) activist, though neither is now active in organised party politics. Being of similar age, we both first voted in 1979, and while voting for different parties, we both lost, though for different reasons. We were also both on the losing side of the devolution referendum of that year. In the 1980s we would describe ourselves as impoverished students, though with post-graduate awards, studying for our respective PhDs while supplementing our income by working on various insecure research contracts. Back then we probably considered ourselves classic disaffected intellectuals, with plenty of time on our hands, few commitments and an arrogant assumption, perhaps in retrospect misplaced, that we could actually influence events.

We became involved in this political publishing project at a very particular point in time, for very similar reasons. Though we had our differences, we both saw the need to try to get self-government back on to the political agenda, and to do that we believed that it was essential to build bridges between the Labour Party and the SNP, to illustrate what could and should be politically possible in a hopefully changed constitutional future.

Working on Radical Scotland allowed the opportunity to proffer a quite different narrative to the then emergent historic orthodoxy which recognised the late Donald Dewar, Scotland’s first First Minister, as the principal architect of the Scottish Parliament project. (2) It was never quite that simple. Seeking to control any narrative always illustrates the underlying and contested nature of power.

Radical Scotland’s prime purpose was to build up a political acceptance that self-government could not be ignored, to make it an issue that would not go away. It was also an overtly idealistic venture in that it sought to bring together what at the time were considered ‘progressive’ left of centre views, to provide a tangible illustration of the idea that, when faced with Thatcher’s Conservative Party, there was more that bound us together than pushed us apart. So the core unifying principle was that if Scotland’s progressive political needs and aspirations were to ever be met, the ‘unfinished business’ of the 1979 devolution fiasco had to be confronted, the problematic issues that had arisen properly addressed, and through doing this, the value of a Scottish Parliament better understood. Our ambition was to make the (re)creation of a Parliament a given for an entire generation of political activists and politicians. And those who did not agree with self-government were to be rendered ‘beyond the pale’. The magazine was thus twin-tracked and inter-linked, in that it was to be a forum for setting down and exploring left-wing arguments and ideas, while arguing that for them to become a reality, self-government was required.

The political landscape we were viewing back then was, however, bleak. In the years following the referendum, most politicians and political commentators considered devolution ‘dead and buried’. The outcome of the 1979 referendum had proved a disaster for both Labour and the SNP, with both blaming each other for their own misfortune, which really missed the point. For the SNP, the Labour Party had failed to deliver, having been unable to marshal its own MPs. It had been a Labour MP, George Cunningham, who introduced the mandatory ‘40% Rule’ which effectively scuppered devolution, despite the small majority vote in favour. But to Labour eyes, it had been the SNP which had brought down their government, opening the door to Margaret Thatcher. Departing Prime Minister James Callaghan’s infamous jibe about the SNP being “turkeys voting for an early Christmas” still resonates. Consequently, any chance of collaboration between the SNP and Labour became impossible. Both were in a hole and neither thought to stop digging.

By 1983, with a General Election looming, polls showed it was certain that Thatcher would again triumph in England, given her inflated popularity, bolstered by the political dividend of the Falklands War. Previously entrenched posturing and positioning by the opposition parties then began to move, albeit imperceptibly at first. These thaws and cracks in ‘official’ party positions started to become more apparent and pronounced. If there was going to be any real change it would be necessary to find the means to bring together people from various political backgrounds and none, in order to find common cause in reviving the case for self-government. There was, therefore, a need to find ways to build bridges, rather than simply retreat into the respective political party bunkers and continue publishing newsletters which spoke solely to those already huddling together.

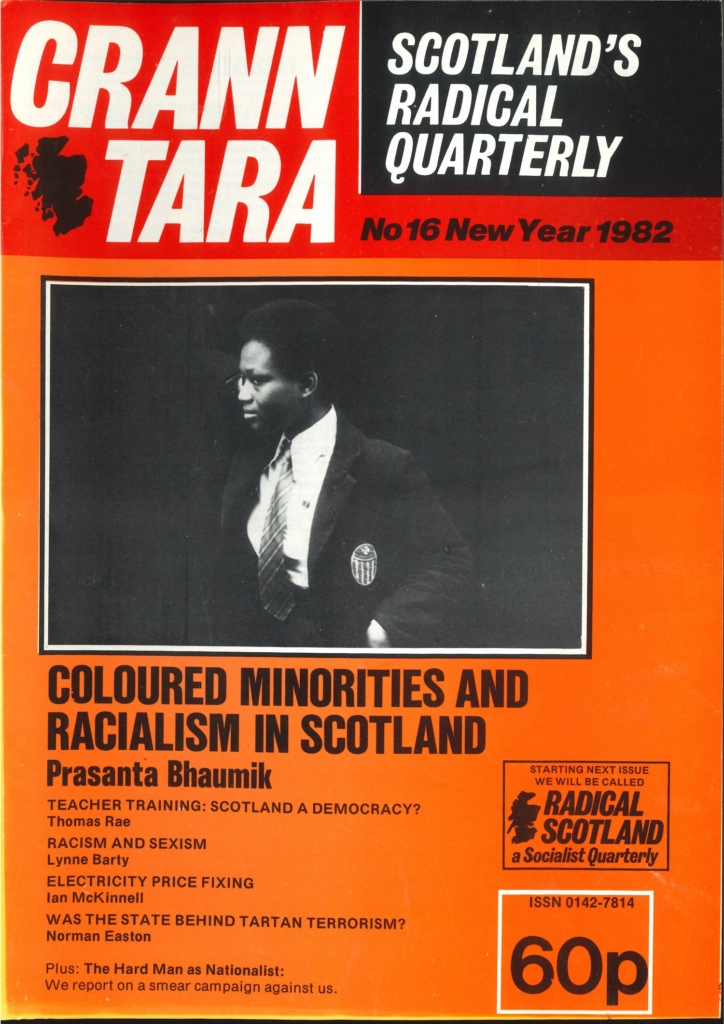

It was early in 1983 that Radical Scotland was launched. Well, that’s not entirely true, given that the magazine already existed. It had been running since 1977, published by a quite different group of people, originally titled Crann-Tàra, before being re-badged as Radical Scotland. What changed in 1983 was that an almost entirely new collective was invited to take it over. This transfer of personnel occurred because members of the incoming editorial team were looking for a new venture, given that they were all heading out of SNP following its annual conference decision to proscribe internal groups. The 79 Group had been formed following the failed 1979 devolution campaign with the stated aim of stimulating left-wing political discussion and debate within the SNP. In the main, the 79 Group also favoured a more gradualist, devolutionary position rather than the fundamentalist ‘Independence, nothing less’ mantra pursued by the then party leadership. Both Margo MacDonald and Stephen Maxwell, key 79 Group founders, had long advocated this gradualist position, whereas others such as Gavin Kennedy and Roseanna Cunningham were more comfortable with fundamentalism. More controversial, however, was the Group’s republicanism, which directly challenged the SNP’s long held “Queen and Commonwealth” constitutional stance, post-independence. Overall, the 79 Group wanted to ensure that the SNP adopted a distinct left-leaning political agenda, rather than continue as a broad-based, somewhat apolitical ‘home rule’ pressure group.

The 79 Group’s overt attempt to take over the party to hasten that political shift suddenly stalled when it found itself proscribed, and its entire executive committee expelled. The man who would later become First Minister, Alex Salmond, and his Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill, were two of those expelled, the others being Stephen Maxwell, Brenda Carson, Andy Doig, the Secretary Douglas Robertson and the Group’s Treasurer, Chris Cunningham.

The 79 Group had an in-house magazine, 79 Group News, and it was the team of activists around that publication who were invited to take over Radical Scotland. Two 79 Group supporters, Graeme Purves and Selyf Morgan, helped facilitate that transition. The new collective, under the editorship of Kevin Dunion, another 79 Group member, who was then working for Edinburgh University’s Student Association, set about broadening the magazine’s political base. Initially Jim Smyth, a history PhD student at Edinburgh University, and Neil Robertson, political aide to Labour MP George Foulkes, were the sole Labour Party members. They were later joined by another Edinburgh post-graduate student and now successful author, James Robertson and journalist Andrew Marr, who both held socialist and nationalist sympathies.

Unlike the nationalists, the Labour Party members were not seeking a new home; rather, they were deeply disaffected by Labour’s apparent desire to withdraw from the entire devolution project. The nationalists were Alan Lawson, who became the second editor, Chris Cunningham, Douglas Robertson, Graeme Purves, Crawford Cumming, Ian Hepburn, Liam Hamilton and Niall Brown. The latter two left within a year to pursue careers as journalists in England. Later the collective was joined by an ex-Communist, John Fairley, who had returned to Scotland after working for the Greater London Council on local employment initiatives. Other political hues on this ‘broad left’ spectrum came and went, but were never central figures in the magazine. Although over the years some left and others joined, these were the core members of the collective up until 1988. In its last three years, the editorial board experienced greater flux, producing a more politically diverse membership.

The age profile of the magazine’s collective was young, between 20 and 35, and the majority were either holding down their first job or were still students. As the observant among you will have noted, it was also all male. Despite much effort to encourage women to join the collective, none stayed more than a couple of meetings. It was not until its later years that a number of women joined the editorial board, namely Mairi MacArthur, Joanna Cherry and Maggie Sinclair.

That said, throughout its existence, the commissioning process sought out a broad range of writers. Gender politics was, as always, a significant issue and explored in various articles by authors such as Esther Breitenbach, Alice Brown, Liz Collie, Joy Henry, Isobel Lindsay and Alexandra Menzies. There was also a range of major articles on the role of women in the peace movement, a major issue at that time given the UK’s deployment of Cruise and Trident missiles. Women’s roles in employment policymaking, health practice, environmental matters, culture and international affairs were also explored. Women’s representation in the proposed new Parliament also proved to be a major topic.

The marked gender imbalance in the early years also says much about the nature of politics at that time. In 1979, out of the 72 MPs representing Scotland, there was but one female member, rising to two in 1983 before eventually jumping to three by 1987. (3) These failures were challenged head-on by the creation of the magazine Harpies and Quines involving a Glasgow-based seven-member women’s collective which included Lesley Riddoch, Jackie Erdman and Catriona Stewart; though as with most other radical publications, it was to experience a brief shelf life. (4)

Given the party political backgrounds of the collective members of the Radical Scotland team, it should come as no surprise this was essentially an elitist project. Hence, the magazine never saw itself as a mass circulation publication, but rather one fronting what was an overtly political project. In the words of Kevin Dunion, the first editor, “The project, for the Radical Scotland team, has always been more than the production of a magazine. The magazine itself has been at the service of the project – that is, pursuing the cause of self-government for Scotland.” (5) So the target audience was Scottish politicians and their foot soldiers, and the message was that progressive politics required self-government, and vice versa. This was to be presented as the inevitable trajectory and ambition for Scottish politics.

The collective had good connections with self-government elements in the Labour Party, the SNP and the Liberals, as well as those in the newly created cross-party group, the Campaign for a Scottish Assembly (CSA). Many were the very same people. The magazine provided a vehicle to allow communication, argument and understanding between these individuals, while also offering a means of maintaining campaigning morale, which was considered critical. In this endeavour Radical Scotland was joined by the arts and culture magazine Cencrastus, founded a few years earlier by Glen Murray, also in response to the failure of devolution and the older poetry-focused magazine Chapman, founded by Joy Hendry. There were direct and regular editorial contacts between all three publications.

As has been said, Radical Scotland’s strategy emerged from the political disaster that had been 1979. In a way this made establishing its role that bit easier given the political consequence of that disaster, Margaret Thatcher herself. Thatcher’s attitude towards devolution was unambiguous. She immediately reneged on the infamous ‘Declaration of Perth’, (6) which stated that if Scottish voters rejected Labour’s devolution package, the Conservatives would come back with a better offer. Now as far as the Conservative government was concerned devolution was dead, and, initially at least, it was not at all clear that Labour wouldn’t adopt that exact same position.

Although Scotland rejected the Conservatives in 1979, the party secured more Scottish MPs largely through gaining almost all of the SNP’s seats on an increased share of the vote. Labour won decisively right across Scotland, though not in England. So the administration of Scotland was to be left to an overtly right-wing, radical, pro-market Conservative government. Had Labour’s Devolution Bill been enacted, this would not have happened. However, custom and practice since the founding of the Scotland Office way back in 1888, was that government ministers, in this case Conservatives, would run the Scottish Office, the territorial civil service department responsible for much of Scotland’s public policy.

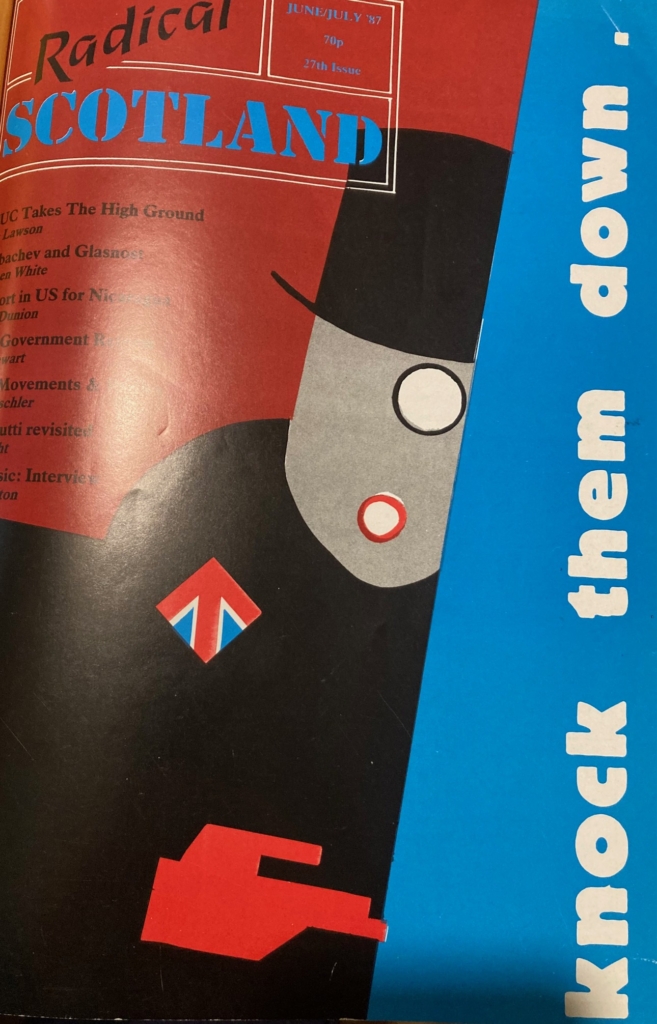

The notion that a governing party ought to have secured popular support in Scotland was then, of course, somewhat novel. The advent of devolution as a policy entity, and the fact that the majority of people in Scotland, albeit by a whisker, had voted in favour of that policy, slowly began to alter thinking. Scotland, though voting Labour, found itself with a Conservative administration running the country. Of course, this idea took some time to take hold where it counted politically, namely, within the Labour Party. In an atmosphere of ever-growing antagonism towards the Thatcher government, and the advent of some tactical voting in certain constituencies, the 1987 General Election saw the Scottish Conservatives’ vote dip to 24% with the loss of 10 MPs, whereas Labour’s vote increased to 42% and they took 50 of Scotland’s 72 seats. Yet, despite such depleted numbers in Scotland, the Conservatives won the UK election, so still ran the Scottish Office. Radical Scotland seized on the opportunity this offered and set about popularising the notion of a ‘democratic deficit’.

The rapid and deep recession of the early 1980s accelerated what had been the long-standing and sustained decline of Scotland’s heavy industries dating right back to the Edwardian era. (7) There were now to be no State handouts to cushion this decline, and there was little on offer to soak up the rising numbers of unemployed. The political impotence of Scotland’s position was all too obvious. While Scots voted Labour to protect them, Labour could do nothing because of its acceptance of the constitutional status quo.

The acrimonious and bitter years of the miners’ strike, stretching out over the winter of 1984-85, served to further cement this perception of impotence. While the Scottish ‘broad left’ supported the miners, the Labour Party officially was distinctly cold, afraid of being drawn into what it viewed as ‘class war’ politics which would leave it exposed to Conservative attacks. Its then leader, Neil Kinnock, decided to just sit it out because he wanted and needed to build support in places where supporting the miners would put people off voting Labour. While some key members of Labour in Scotland went along with this, there was a strong push back, given the broader coalition of support for the miners. Mick McGahey, the Scottish miners’ leader and life-long Communist, was also much respected. The miners were nevertheless defeated. The later campaign against the ‘Poll Tax’ (8) presented a similar sequence of events: Labour distanced itself, again resulting in broader cross-party working, though in that instance the cause was won.

Looking back now, it is easy to see that the so-called Thatcher Revolution was radically transforming Britain economically, politically, socially and culturally. Within 15 years Scotland was no longer an ‘industrial nation’, while its post-industrial future was still largely an unknown. All that was then obvious were mass unemployment and an ever-deepening recession. In common with similar districts of Britain, and across Europe for that matter, Scotland was engaged in lamenting the disappearance of an industrial way of life. At that time we thought that this way of life, which we had been brought up with, had genuine value so needed support and preserving. We were sitting within the vortex of a socio-economic hurricane, unable to fathom what actually was happening all around us, nor appreciate either its scale or significance. The Proclaimers, some years later, brilliantly articulated this blend of political nostalgia and naivety in their famous song “Letter to America”.

During this deeply fractious period, Unionism became identified as a political adjunct to Thatcherism. The voice of the Scottish Conservatives became ever more anti-devolutionist and shrill, a position best articulated by their soon to be Scottish Secretary, Michael Forsyth. Pro-devolutionists found they had no place within the party, so those with such sympathies stayed schtum. Meanwhile, those voices on the Scottish left who previously had so vigorously opposed devolution, were also largely stilled. Stalwart Labour Unionists such as Tam Dalyell and Brian Wilson found themselves effectively shamed into silence.

At the same time, the British Labour Party started to fall apart. Michael Foot’s ineffectual leadership led to internal feuding, making Conservative political ascendancy appear permanent. Foot’s successor Neil Kinnock fared little better. In retrospect, what was so peculiar about the era was the fact that the Conservatives in Scotland appeared to be in terminal decline (making it somewhat ironic that the future creation of the Parliament gave them a major fillip); whereas Labour was reaching all-time highs in its level of electoral support and number of MPs (yet is now but a minority political force in Scotland). While popular British political tracts at the time were entitled, The Forward March of Labour Halted?,(9) and endless hand-wringing conferences were being held up and down the land with titles like “What’s left of the Left?”, (10) Labour in Scotland was experiencing something of an ‘Indian summer’.

The SNP, by contrast, was in self-imposed limbo. Having dealt with its own internal splits, it then found itself unable to project the party as an alternative shield against the Thatcher Revolution, so languished in the polls at about 20% for almost two decades.

From Radical Scotland’s perspective, to continue to oppose self-government was tantamount to supporting Thatcherism. The first argument was simple: if there had been self-government, then Thatcher and her Scottish Conservative cronies would not have been running Scotland. So in line with the magazine’s political ambitions, self-government was aligned with being anti-Tory.

Our second argument, however, represented more of a challenge. If Labour was going nowhere in England, what exactly was Labour in Scotland going to do? If there was no likelihood of another UK Labour government, what would Labour in Scotland do with its popular mandate? The conundrum here was that a Scottish Parliament would only ever happen following a Labour Party UK General Election victory, and throughout the 1980s that appeared an impossibility.

Looking back now, the political context appears desperate. The self-government torch had been all but extinguished, with only its dying embers being fanned by a small number of people who made-up the membership of the tiny CSA. However, the work carried out between the 1983 and 1987 General Elections by these individuals, linked together through Radical Scotland as well as the cultural periodicals Cencrastus and Chapman, helped firm up a set of political assumptions and expectations which eventually ensured that self-government became core to the Scottish political agenda.

For Radical Scotland, it was evident that Labour had to be part of the self-government solution, given it was the only political entity that could actually deliver on it. Yet the Callaghan government’s track record made it equally clear that it would be a mistake to put all our trust in Labour. In any case, with the Conservatives’ political dominance seemingly becoming permanent, it was questionable what Labour could actually do. So would the political ambitions of Scottish Labour only be achieved by engaging fully with the constitutional question, though this would require the party to split along national lines? Would Scottish Labour’s small nationalist-wing become a new party, replicating the ill-fated Scottish Labour Party which briefly emerged in the late 1970s? (11) Or would they opt to join forces with the SNP? All these scenarios were very much in the political mix at that time.

Given the magazine’s political agenda, both form and content had to be brought together. All magazines need to fill their pages with a variety of articles and make these offerings attractive to their readers. Given that our readership was largely composed of ‘political anoraks’, and our political message, broadly speaking, remained the same from the first edition to the last, it was critical that we were able to present that message in a variety of different ways. To do that, we drew on many different and occasionally unexpected voices, with the more unexpected the author or take on the issue, the better. We had to show that emerging political ideas could easily be part of our political lexicon within a self-governing future.

Moreover, the politics of the project were interpreted quite broadly: self-government should never be couched as a narrow institutional construct, solely focussing on functions and structures. Rather it had to be far more ‘catholic’, wide-ranging and challenging. In this way, many in the collective drew inspiration from the then emerging writings of Antonio Gramsci, which had only recently been translated by the poet and political activist Hamish Henderson. (12) These works provided an intellectual break from the long-polarised constraints imposed by Marxist orthodoxy, namely that nationalism was at variance with social revolution. Gramsci allowed many to reframe their socialist ambitions within a specific national context and particular local culture.

A series of articles on radical thinking was produced by Paul Tritschler (13) exploring the broad trends then emerging from Green politics and Euro-communist agendas. Tom Nairn’s Break-up of Britain (14) thesis was also highly influential here, in that it offered a post-British Empire historical dynamic within which contemporary Scotland now found itself.

Hamish Henderson

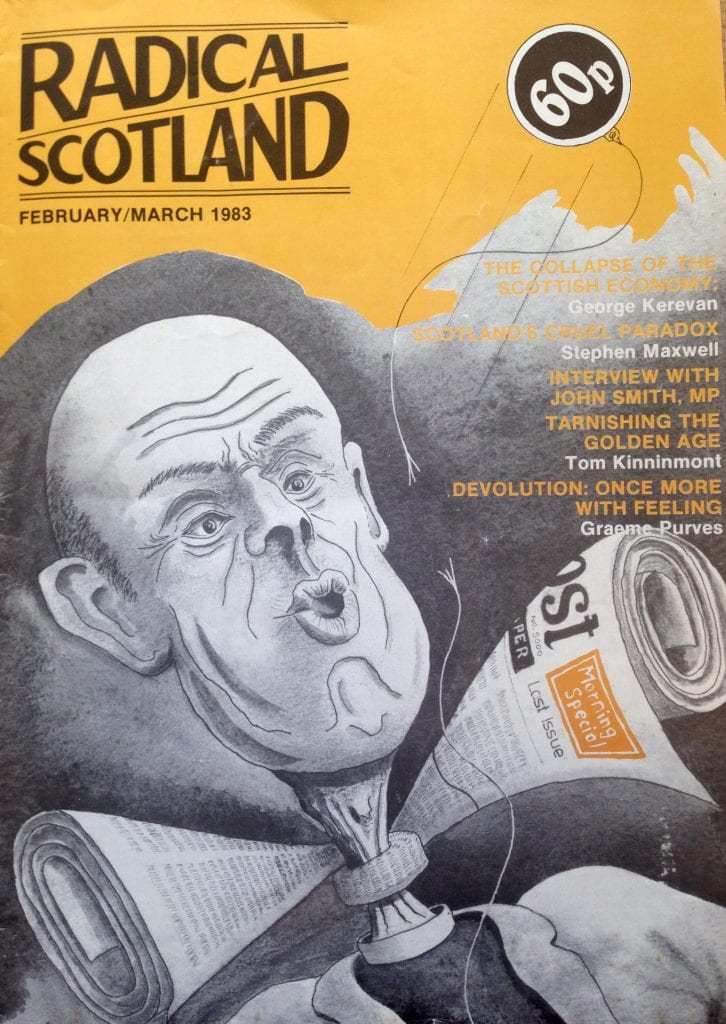

For Nairn, independence became the inevitable consequence of the death throes of Empire, as Scotland sought out new trading and cultural relationships with Europe. This was certainly a debate that Radical Scotland actively sought to open-up, in order to give expression to the view that Scotland could be a more outward looking, socially just and inwardly confident European nation. The political currency of seeing ‘Scotland in Europe’ was later picked up by Jim Sillars, who ensured it long became an SNP political mantra, reversing the party’s previous opposition to membership of the then Common Market. Radical Scotland also delighted in Nairn’s famous dictum, ‘Scotland shall be free when the last Minister is strangled by the last copy of the Sunday Post’, (15) so much so that we created that image for our first edition’s cover.

Picking up on European political dynamics, a great deal of coverage was given to environmental issues, reflecting the emergence of Green politics. In particular, the magazine was very taken with the writings of Rudolf Bahro, a dissident East-German eco-philosopher and Green Party leader, who saw a link with Gramsci in trying to broaden this political and cultural coalition into a wider social movement for change. (16) (17) The predecessor of the Scottish Green Party, the Scottish Ecology Party, had been launched during the 1979 devolution referendum campaign, and its members provided regular copy on environmental issues, especially on nuclear developments and dumping.

As with the precursor periodicals Calgacus and Crann-Tàra in the 1970s, there was also a strong focus on land reform, given that Scotland, almost uniquely within Europe, remained tethered to feudal land ownership laws. Sexual politics were also prominent, as they had been in Crann-Tàra, though given the times, this caused a few challenging discussions and debates within the collective which would now seem quite odd. There was also much coverage of domestic social policy since collective members had a direct interest in many of these areas, including welfare reform, housing policy, local employment initiatives, tourism, planning, arts policy and the role of quangos. Irish unification also featured, given its continued prominence and the fact that the ‘H Block’ hunger strike had only recently concluded.

Both Kevin Dunion and Alan Lawson, the second editor, were extremely well connected and both had an ability to actively seek out new people to contribute ideas and articles to the magazine. They also drew on the collective’s diverse and varied range of contacts and interests. Commissioning articles was something of a personal endeavour, which involved seeking out a possible contributor, so finding an address or telephone number. Then after a chat or face-to-face meeting, and usually follow-up telephone conversations, hopefully a type-written script and photographs would be received by the agreed date. Dunion, who later went into foreign aid work, also had a good grasp of what was happening in Latin America at that time, so the political crises in both El Salvador and Nicaragua received prominent coverage. So did apartheid in South Africa, helped by the fact that another collective member, Neil Robertson, had previously worked in Lesotho.

Good contacts also existed in certain development charities, such as Stephen Maxwell who ran Scottish Education and Action for Development (SEAD). Such contacts allowed us to secure many insights rarely covered by the mainstream press. The domestic politics of a variety of European countries also regularly featured, again generally commissioned on a somewhat serendipitous basis, involving who had recently bumped into so-in-so, and they had observed this or that, about this particular place. To a degree, this approach mirrored that still pursued by the BBC’s Gaelic current affairs programme Eòrpa. (18)

Radical Scotland also tried to organise a study tour of the then Soviet Republic of Georgia, but it had to be abandoned due to Soviet bureaucracy. To an extent what we attempted, but did not really succeed in doing, was to provide a Scottish viewpoint on global events. The Scottish media has always been stubbornly parochial, failing to do justice to international affairs. Now, as back then, if you want a global perspective, it can only found in the now diminished ‘quality’ London press.

The magazine presented its content as ‘radical’, but to a degree that was ‘over egging the pudding’. Much of the published output did not strictly conform to a ‘radical’ tag. Rather, it was often just different, challenging and hopefully thought-provoking. ‘Radical’ was a convenient unifying label on which to hang things, and something of a ‘mobilising myth’ underpinning what were in reality basic reforming ideas which we considered could and should be the norm within a progressive self-governing context.

And so, Radical Scotland in the mid-1980s was imbued with a committed editorial team, good connections within and outside of the political, cultural and journalistic establishments, and a clear aim: to overcome the hostility of the Thatcher era and put self-government front and centre in Scottish politics. In the second part of this article, we’ll examine the strategy, the hurdles faced and the progress made as the magazine went about its challenging mission.

I wonder if European green politics wasn’t lagging behind what was rather condescendingly called the Third World then and now? I’m thinking for example of the likes of this kind of ecologically-informed good life philosophy:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sumak_kawsay

which have made it into national constitutions, or been proposed for them.

On reflection (I don’t know if I was ever aware of this magazine) was the Radical title justified by the apparent fixation on tribal party politics? I wonder if the term ‘radical’ is often simply used to mark a boundary of the Overton window — thus far but no further — rather than extend it.

I attended the ‘Crann-Tara’ supporters’ group meeting that took the decision to change the magazine’s name to ‘Radical Scotland’. The change was timed to coincide with the transfer of the editorial baton from Norman Easton to Ian Dunn. There was a feeling that the existing title was perhaps too esoteric, or might convey the impression that it was a Gaelic or cultural magazine rather than a political one. The aim was to come up with a title which would have wider resonance. A Welsh friend who was present mentioned ‘Rebecca’, the Welsh radical magazine named after the Rebecca Riots in West Wales in the 1840s. In choosing ‘Radical Scotland’, the supporters’ group consciously sought to invoke Scotland’s radical political tradition, while being aware that that tradition had been subject to romanticisation, like much of our history. I think Douglas Robertson sums up the magazine’s content very well.

I think a Scottish perspective on green politics began to be articulated more strongly with the launch of ‘The Tree Planter’s Guide to the Galaxy’, now the ‘Reforesting Scotland’ journal, with which people like Andy Wightman, Bernard Planterose, Fi Martynoga, Alistair McIntosh, Karen Grant, Donald McPhillimy and Mark Ballard were associated.

@Graeme Purves, I presume there is an international connection between Scotland’s rainforest advocates and other groups worldwide? What I haven’t seen is a major Scottish political movement to put an ecologically-centred ‘good life’ philosophy at the heart of a new national constitution post-Independence.

#biocracynow

These international connections were present from the outset within the team that launched ‘The Tree Planter’s Guide to the Galaxy’ in 1989, and the ‘Reforesting Scotland’ journal has been promoting an ‘ecologically-centred ‘good life’ philosophy’ for more than 30 years now.

As to why such a philosophy has not been reflected in the policies on climate change, woodland expansion, marine conservation and land reform pursued by the SNP and the Scottish Greens in government, I think you would have to take that up with politicians such as Patrick Harvie, Lorna Slater, Màiri McAllan and Gillian Martin. Perhaps they have not read widely on environmental matters?

I flirted with the Radical Independance Campaign during the 2014 referendum campaign. I presume this are will be covered in part 2?

If the long tail of history, voices of reason and excellent writing could swing it, the case for independence would surely be won. I was not actively or intellectually engaged with the case for independence – beyond thinking and voting – when these publications were around but have become more ‘radicalised’ with age and time to look beyond work and raising a son. Huge appreciation to all who have kept – and keep – the flames of honesty, humanity and autonomy alive. I look forward to reading part 2 as well as reports on the great line up and turn out for Saturdays ‘Break up of Britain’ conference. May you never give up!

Whatever became of Alan Lawson? He seemed to vanish after Radical Scotland.

Moved to Angus and ran a successful brewry for a few years.