On Dùthchas and the Protection of the Intangible Cultural Heritage

On Dùthchas, ‘heritage “from below” and the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Today, 23d December, the British Government announced its intention to ratify the Convention for the Protection of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (CICH). Many advocates (like me) have waited for years for this welcome announcement, and it is fitting and symbolic that it occurs close to the winter solstice. In June 2020, the Conservative Government said that, while recognising the value of UK crafts, oral traditions etc. for the country’s cultural life, they could not see any compelling business case for ratifying the CICH, nor was it clear to them that the benefits would outweigh the costs. Moreover, it was important to prioritise resources for those conventions that really impacted on the safeguarding of heritage (e.g., the 1972 World Heritage Convention and 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict). Earlier this year, the Government affirmed that it was keeping the matter under review, but finally the welcome announcement came that the UK Government is set to ratify the Convention.

So, what is the CICH?

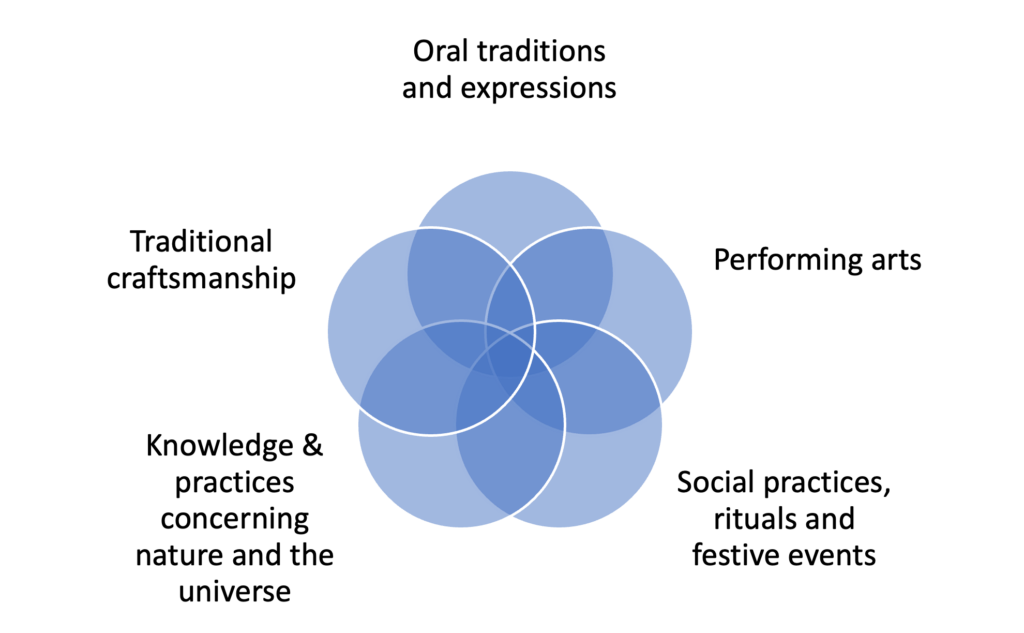

It is 20 years since the CICH was adopted at a UNESCO meeting in Paris. The aim of the Convention is to give value to aspects of heritage that were not given due recognition in previous conventions – and in particular to the living heritage of ordinary people. The CICH grouped this heritage into 5 categories as outlined in the image below.

For those of you interested in delving deeper, I can recommend Mapping Intangible Cultural Heritage Assets and Collections in Scotland (2021), which was commissioned by a range of national organisations and undertaken by Steve Bryne, recently appointed as Director of Traditional Arts & Culture Scotland (TRACS).

Why is the CICH relevant for Scotland?

Earlier this year, in the summer ICOMOS newsletter, I drew attention to the Scottish-Gaelic word Dùthchas, which translates as ‘heritage “from below”’ or ‘from the ground up’. Alan Riach expertly describes it as ‘the word that describes understanding of land, people and culture’.

As explained in my TEDx talk on ICH, other terms that are commonly used include living tradition or public folklore are terms. The concept of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) is clunky but is well explained in A Wee Guide to Intangible Cultural Heritage from TRACS. That TRACS Guide gives examples, such as bothy ballads, the Galoshins, the Burry Man of South Queensferry, Beltane, and the much-loved Hogmanay. Over time, Scotland has developed strong expertise in recording and safeguarding its ICH, if not always explicitly identifying it as such. Many renowned Scottish folklorists and ethnologists, including Margaret Bennett, Hamish Henderson and Colum McClean, have recorded and documented Scotland’s living traditions. The revival of Beltane celebrations in Edinburgh illustrates the creative ethnology inspired by their work.

Beltane celebrations on Calton Hill, Edinburgh © Ullrich Kockel

What is the Inventory?

One requirement of the ratification of the Convention is the establishment of a repository of ICH. Scotland already has two such inventories. One inventory is the Tobar an Dualchais/Kist o’ Riches project, hosted by Sabhal Mór Ostaig, University of the Highlands and Islands, and the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh. This archive displays online the knowledge and practices of tradition-bearers in Scotland. There is also a repository, commonly known as the Scottish ICH Wiki, hosted by Museums Galleries Scotland (MGS). Going forward, it will be interesting to see how the UK manages the process of listing among the four nations.

Scotland’s strengths

Scotland has strong expertise in all five domains of the CICH. One of these is in the field of knowledge and partnership concerning nature and the universe. Scotland’s expertise in this field is outstanding. If one looks at Meg Bateman and John Purser’s monograph, one can see that the Gaelic tradition is brimming with traditional ecological knowledge. John Muir is popularly conceived of as the father of national parks in the US. There are also the nature writings of Nan Shepherd (The Living Mountain), and Patrick Geddes, associated with the dictum that we should think global but act local.

Debates regarding the relations between humans and the landscape feature regularly in Bella Caledonia, with contributions from the likes of Alastair McIntosh, Mairi McFadyen and Raghnaid Sandilands. There have been some recent studies on the links between ICH and the environment (for example on the relationship between musical heritage and the landscape by the Glenmoriston Improvement Group), but much more needs to be done on ICH and the ecosystem in Scotland and the UK more widely. Given the current climate crisis, this domain has a particular urgency.

Traditional craftsmanship was identified in the Mapping ICH in Scotland report as a domain in need of safeguarding. Unfortunately, some of Scotland’s traditions are at a critical juncture. Fair Isle straw back chair making, Highlands and Islands thatching, Northern Isles basket making (kishies and caisies), and sporran making all feature on the Red List of Critically Endangered Crafts, compiled by Heritage Crafts UK, an organisation that has vigorously campaigned over the years for the ratification of the CICH. Activities designated as endangered include Kilt making, Orkney chair making, Sgian dubh and dirk making, as well as Shetland lace knitting. Skills such as Bagpipe making (Highland pipes), dry stone walling, and Harris Tweed weaving are still considered viable but need additional help.

Although Scotland is at a critical juncture in terms of traditional skills, it is important to recognise the significant work being undertaken by some organisations. The Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh regularly profiles skills of song and story. Historic Environment Scotland (HES) supports traditional building crafts. Great credit is due to the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities, which has facilitated academic research with industrial partners in the field. I work at the Institute for Northern Studies, University of the Highlands and Islands, where postgraduates along with communities of practice are co-researching the craft of dry-stone walling, the cultural practice of thatching, and the building of the traditional Orkney Yole.

dry-stone walling (c) Niamh McKenzie

Some challenges ahead

The UK Government’s intention to ratify the CICH, announced this morning, creates very welcome opportunities, but we should not underestimate the challenges ahead. One challenge is the strong desire of many groups to feature not just on a Scottish or UK Inventory, but also on the international Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Register of good safeguarding practices, which the UK Government proposes not get involved in for the first few years. How will the race to get on the list be managed, and what about traditions such as marching, which can generate considerable tensions?

Another challenge will be the issue of migrant heritage. Traditions new to a locality or region are technically excluded from CICH listing as they have not been handed down in place from one generation to the next. In contrast to many countries, migrant (“new Scot”) heritage is included in Scotland’s ICH Wiki. There you will find examples of the Chinese New Year, Dragon Boat Racing, The Mela in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and Mehndi skin decoration.

And how will the ratification of the CICH impact on the consolidation of ICH in partnership with relevant organisations in Scotland? An excellent example of recent collaboration was Scotland’s Year of Stories (2022), which was a year-long celebration of Scotland’s rich storytelling tradition. How will Scotland build on that legacy of collaboration in the new context of ratification, and what networks can be built across the different nations and regions of the UK? There is already tremendous work being done by The Scottish Storytelling Centre, Creative Scotland, HES, MGS, National Library Scotland, TRACS, as well as universities and other bodies, but the ICH landscape is still fragmented in terms of guidance, encouragement, and resources, and much more needs to be done.

On 30th December, I am involved in an Radió Teilifís Éireann Radio 1 programme about the benefits of the CICH to Ireland since the country ratified it in 2015. As a New Scot (an Irish person living in Scotland for over 12 years), I can only hope that Scotland – and the rest of the UK – will be similarly pleased with the new context of ratification. Today’s announcement is a cause for celebration and optimism for a new era. A process of consultation will follow, lasting until the end of February. At a juncture that marks the beginning of longer days and more light, we can also celebrate a new era for ICH in Scotland.

There is nothing intangible about bothy ballads. I’ve got a book of them that actually exists in my house, they are actually performed at real folk clubs, and there are real, actual recordings. Can you really get a tangible job pretending that such things are intangible? That would be very challenging, but very Far Out. But I suppose it depends on what people you would be trying to convince – perhaps a small clique who require little persuasion because thay are the only people who give a shit about this twaddle because they invented it?

I’m all for preserving folklore and traditional skills, but I don’t have a particularly rosy view of Scottish traditions such as Hogmanay, which our family ditched once the auld folk were gone, as a maudlin collection of empty ritual, self-delusion and alcohol abuse. Some traditions reinforce hierarchy, patriarchy, primitive ancestor worship; are composed of superstition rather than knowledge; have been nobbled and garbled by later authority (such as Christian clergy); and/or packaged for commercial exploitation. Traditions which aren’t particular harmful can still be baggage best discarded, as our ancestors no doubt discarded much of theirs. And shouldn’t be forced on people, as we were forced to do Highland dancing in school.

Perhaps some people feel blessed, enriched and enabled by their Scottish ICH; I am struggling to recall anything particularly useful. Which goes for religion and those marches the article mentions. I suspect Irish ICH may be in a stronger position overall; certainly it seemed to be easier to access Irish and Welsh folklore and mythology than Scottish versions when I was younger.

It was when working in the South Pacific that I first heard people say, “we didn’t know we had it until we lost it.” That’s why this UN initiative is important.

I’m coming across so many examples of the intangible teetering on the edge. One example, a retired policeman in Skye said to me just this week how oral history so easily slips away. For his research (which is into aspects of Hebridean religion in the Point district of Lewis) I was able to put him in touch with a 94 year old woman who is still as sharp as a pin in her mind. He called her, and she was pleased to be able to set down in what will become his next book that which she carried from her youth.

Another Lewis example is a crofter talking about the village peat workings, and his concern that these days, too few people realise how the markings on the land double as markers of belonging for different families. He was aware, being the chair of the local historical society: but what I notice in many such tradition bearers is that they carry a sense of burden until they feel able safely to rest it down, from where others can pick it up. Why so? Because often they know it to be a precious burden.

I have also become mindful of the importance of the dusty work of archivists. Camille Dressler, a long term Eigg resident who originally trained in ethnography at the Sorbonne drums that into me whenever I go there, as does Catherine MacPhee the archivist for Skye & Lochalsh, with many local events. Often, there are “implicit meanings of local practices”, and these weave warp to the weft of our social cohesion.

@Alastair McIntosh, on preserving South Pacific culture, I searched for who funded video game Tchia, and it seems to have been privately funded (by Kowloon Nights, according to Wikipedia) rather than receiving, say, UN or French support.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tchia

What’s essential to intangible cultural heritage is its very distinction from the traditional fixed or material heritage of a nation, such as its collections of bothy ballads or other artefacts and canons thereof, which is usually curated by some class interest. Intangible cultural heritage is precisely those forms of life that normally fall outside or are excluded by that curation, transgress established cultural classifications and categories, are less governed by established criteria of worth (‘good’ and ‘bad’), and are owned by people themselves rather than by established cultural institutions.

My beef with the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the UK government’s implementation of it is that it’s an attempt by the establishment and its institutions to appropriate those marginalised and transgressive forms of life to its ownership, to make them part of a society’s fixed or material heritage, and to thereby, in effect, neutralise them as sites of resistance to the dominant culture and the power relations it expresses.

It’s vital to intangible cultural heritage that it retains its ‘critical moment’, that it remains marginalised, outside of and transgressing our fixed or material heritage and its institutions. Otherwise, it’ll cease to be ‘intangible’ and become part of the ‘materiality’ of the current establishment through which power is exercised in our society.