Hard Talk on Leith Walk

Public libraries have been squeezed and under threat for many decades; a manifestation of what David Marquand and others see as a long running assault on the public domain. Thankfully, many in the city seem to be in good health and well used. One of Edinburgh’s busiest public libraries, McDonald Road, is currently celebrating its 120th anniversary. They are commemorating this with exhibitions and a series of talks.

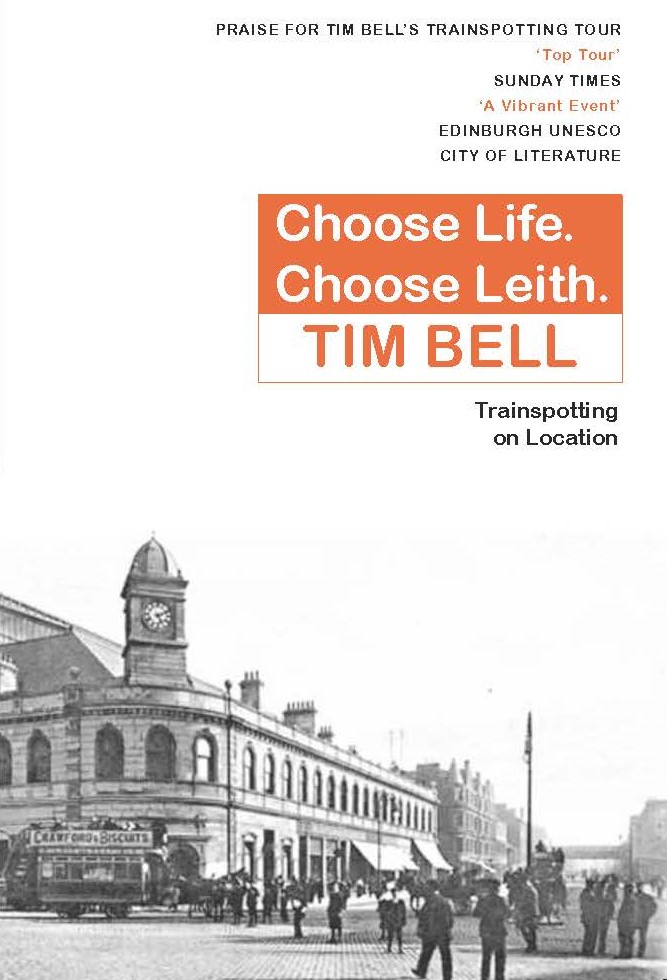

The local author, social worker, and tour guide Tim Bell kicked off the series with a rich and engaging (and at times moving) talk on the history of Leith and Leith Walk – ‘Small Talk on the Walk’. The room was packed – the healthy appetite for local history in this area was clear. Inter- weaved in his narrative were some of the themes from his book Choose Life, Choose Leith, (a 2nd edition is due out later this year) which looked at the social background to Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting. Bell has had a long relationship with the book, evident in the battered copy he read from; full of post-its, and with its binding falling apart.

Underlying his talk were themes of social regeneration achieved through culture. Bell has been a leading figure in the Leith Writings project, which has so far produced three volumes of short stories, poetry and drawings – which offer delightful sketches of Leith. The contributors to these volumes are locals, with a high proportion written by school pupils (especially from Trinity Academy). The project is ‘self-consciously community orientated’, with the contributors reflecting the changing character of Leith. Contributors this year include a young Ukrainian girl and a Muslim German.

A considerable place

Bell began the main part of his talk picking out key aspects of Leith’s evolution and its often tense relationship with Edinburgh. Its status as a highly significant port and industrial centre saw it become a considerable place in its own right. There was a short period where it was possible to say that “Edinburgh was a Suburb of Leith”, not vice versa. For example, Leith Races were the biggest social event in Scotland in pre-industrial days. Leith was also the true home of golf, with the original rules drawn up by John Rattray at Leith Links. Bell was part of the effort by the Leith Rules Society to get a statue of Rattray installed on the links (made of bronze by Scottish sculptor David Annand, it sits near the junction of Salamander Place and Links Place).

Bell was keen to remind the audience of the scale of industry in Leith. Salamander Street was a hugely industrial area, often referred to as ‘the street with a hundred smells’. The area where Ocean Terminal now sits was a shipyard. It was because of this significant industrial base that de- industrialisation hit Leith particularly hard. From the 1960s onwards, the area went through massive change. The loss of the old Kirkgate and its “organic intimacy” typified this sense of decline. Significant institutions closed including Leith Theatre and a Hospital, creating a sense of lost civic pride. Many people were moved out of the slum areas to some of the peripheral housing schemes, such as Craigmillar; with them went large chunks of the old Leith community. The mammoth blocks of flats built in that era proved largely unsuccessful, with 50% of them now demolished. As Bell remarked, “What a waste!”

Hollowing out

For Bell, the fate of the old Leith Central Station, opened in 1903, closed in 1953, and finally demolished in 1989, typified this hollowing out. For Bell, the loss of this vast building was a “huge wasted opportunity”. Its sheer scale meant that it could have been a focal point for regeneration in the area. It could have been some sort of arts complex; an architect Bell showed round said “you could have put a Guggenheim in there!”. In recent decades we have seen a far greater willingness to try to find new uses for old buildings. Imaginative repurposing has become fairly common. Take for instance Edinburgh Printmakers, who have beautifully restored the last remaining building of the once vast North British Rubber Company.

Perhaps Leith Central Station would now be mothballed rather than allowed to disintegrate and fall victim to vandalism ? However, finding new uses is never easy – evidence by places such as the Custom House. Similarly, the process of finding a new public use for the Old Royal High School has been tortuous.

The fate of the Leith Central Station was, for Bell, an example of lost potential – and the way that so many lives were wasted during these hard years of industrial decline. As Bell noted, it all happened so quickly – so many were left scrabbling around to find alternative employment. Surviving the shipwreck, to use William McIlvanney’s description of the impact of Thatcherism on Scotland, was far from easy. Hard drugs became an escape for many. The dealing culture that emerged, in places such as Albert Street, sent Leith further down a spiral. Leith grew in notoriety, often shunned by respectable Edinburgh.

Bell ended powerfully by reflecting on the photo which adorns the front cover of his book. It’s of a group of young men near the Foot of the Walk, taken shortly before World War One. It made him think of a similar group standing there in the 1980s. In the case of the old photo, many of those featured would die in the war. In the 1980s, many of the equivalent group would have their lives wrecked and shortened by drug abuse – and perhaps AIDS. Bell himself is closely involved in the world, working with Anyone’s Child organisation which campaigns for safer drug control.

Two Leiths?

The way that the area’s image has changed radically in recent decades makes it difficult to comprehend this dark period in its history. These days Leith is seen, by the likes of Donald Anderson, as a classic example of successful urban renewal (or gentrification, depending on your point of view). Its creative energy and dynamism certainly draw many to it.

After the talk I made my way down the walk, enjoying the crisp sunshine. Towards the Foot of the Walk I stopped for a coffee – I needed somewhere to sit and absorb the talk. The specialty coffee place I sat in used to be a funeral directors: a rather clear manifestation of rebirth. The many new businesses in this section of the Walk (such as Argonaut Books) seem to represent the contemporary media cliche of an area that has changed out of all recognition and is now one of Europe’s ‘coolest neighbourhoods’ .

But, as I gazed across at the last remnants of Leith Central Station, Bell’s recounting of the gloomy social realities jolted me out of my daydream. Caffeinated, I made my way across, dodging trams, to Tesco’s car park, where the sidewall of the station remains as if the last vestiges of a ruined fort. This gives some inkling as to the truly massive scale of the site and the way it continues to represent an unhealed scar in the heart of Leith.

The difficulties councils are facing in sustaining a public library service are, I suspect, a covert part of the ‘culture war’ which the Conservatives (and to an extent assisted by the Liberal Democrats and Labour) have been waging since the 1980s, by the increasing restrictions on public expenditure and by establishing a hegemonic idea that public expenditure diverts money away from ‘important things’. They created ‘straw man’ fallacies about allegedly ridiculous uses of public funds. The actions of the Greater London Council in widening access and providing support for various minority groups were habitually ridiculed in the media and provided the pretext for Mrs Thatcher’s scrapping of the GLC and ‘balkanising’ the governance of London.

With the advent of the Con/LibDem coalition in 2010, and the nastiness of ‘austerity’, the culture wars ramped up. Funds for councils were reduced in real terms and Westminster curtailed councils’ powers by specifying criteria for public expenditure. Gradually, this forced councils into increasingly difficult choices between things such as almost existential supports for very disadvantaged groups and services such as libraries, parks and playing fields.

And, of course this provided the right wing media with the opportunity to ‘slam’ councils for having made very difficult choices. And, the ‘slammings’ usually included vox pops from poor people who had lost things like library access. And, there were also the performatively angry campaigners who could be relied upon to excoriate local councillors. It is classic divide and rule tactics.

Sadly, we see these tactics being deployed by Labour politicians aspiring to display their ‘iron clad adherence to fiscal rules’. Mr Wes Streeting said the doctors that they could either have a pay rise or they could improve services to children; THEY CAN’T HAVE BOTH.

‘performatively angry campaigners’

How do you distinguish which campaigners are ‘performatively angry’ ?

With your eyes and ears?

I am almost surprised that evil corporations didn’t turn those abandoned public buildings into deathmatch arenas. I’m pretty sure the ancient Romans were successfully repurposing their public architecture ages ago. Or leased as sets to creatives making movies about future dystopias or old-timey foreign cities, depending on the state of decay?