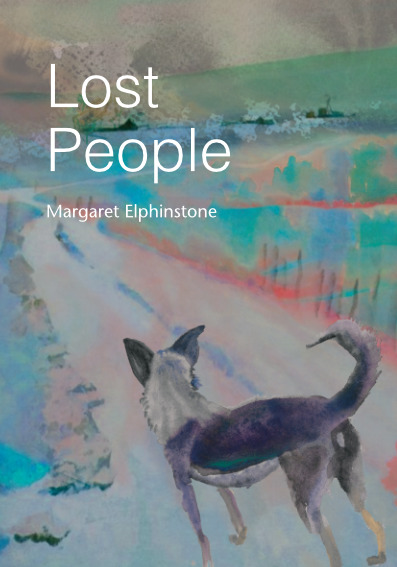

In Praise of Mutuality, a review of Lost People by Margaret Elphinstone

A young refugee is left in the care of a monastery and sanctuary; just another child displaced by war, abandoned by a woman who may or may not have been their mother.

Lost People by Margaret Elphinstone isn’t explicitly about climate change; it’s not ‘cli-fi’, to use the clumsy name given to the genre, but it is a novel for the Anthropocene, for a time haunted by the prospect of systemic collapse. It’s short – a novella – written in simple, lucid prose, and in tune with the allegorical nature of the tale, we don’t learn specifics: we’re never quite sure if the child is a boy or a girl, and even their name, Rue, is self-chosen, after the plant. Likewise, towns, cities and countries are unidentified, and no reference is made to the states or authorities who preside over the war that has destroyed civilisation. The book is not concerned with geopolitics, but rather with how people and communities survive catastrophic events, how they muddle through, bearing their trauma – lost people trying to find themselves again.

Elphinstone has grappled with this theme before. In The Gathering Night, her previous novel, set during the Mesolithic Era, key characters survive a tsunami that devastates the communities scattered along the north east coast of Scotland. And in ‘The Meniscus Moment’, an essay written in 2013 for Dark Mountain, Elphinstone reflects on the collapse of the Roman Empire and the fate of those who live through it. Referencing Rosemary Sutcliff’s novel, The Lantern Bearers, and a play by R.C. Sherriff, The Long Sunset, she writes:

Several years before anyone explicitly told me that our own civilisation, like that of the failing Roman Empire, was also in its long sunset, I already knew the story. The image of the long sunset, and finally the last little light, belongs deep down in my mind. I have always known that no civilisation lasts for ever.

But what comes after? Contemporary references are invariably dystopian: Mad Max, The Road, The Last of Us; desperate people in guarded compounds, fighting off marauding savages. Lost People offers a gentler vision, a useful corrective to those that seem to glorify our capacity for violence. There’s nothing gratuitous in the novel, and only once are we jolted by a flashback, when Rue remembers an attack by soldiers on their house and family. Elphinstone doesn’t gloss over the physical and psychological wounds carried by those who survive a war, but nor is she interested in picking at the scabs. Instead, she attends to the notion that wounds require time to heal.

Initially, Rue’s is a constricted world. Spikey, possibly autistic, they struggle to trust or to receive help; but at the heart of Lost People is an insistence that self-reliance will only take you so far. Reaching adulthood, Rue leaves the care of the monastery and makes their way through a post-war landscape, encountering, in the main, hospitality and reciprocity. They help with the tending and harvesting of crops and receive shelter and food in return. Eventually, they team up with a spice merchant and become a wandering peddler, providing scattered communities with exotic spices – tastes they thought they would never experience again.

In our own time of war and accelerating climate change, it can be hard to hold to a positive vision of the future; but one of the things that fiction allows is the chance to consider all the possibilities. Lost People is not naive, it doesn’t offer utopia, but instead a reminder that our existence as a species is predicated on mutuality rather than conflict; and that it’s only relatively recently, here in the West, that we’ve abandoned an agrarian, hand-crafted economy.

This is what Elphinstone holds up as an option, perhaps an aspiration: people returning to subsistence, to working the land and tuning to the rhythm of the seasons. When Rue is first abandoned at the monastery, they’re drawn to the knot garden, an enclosed but neglected garden laid out in four quadrangles. They begin to grow herbs there, for the kitchen and the apothecary, and the names of herbs and flowers are repeated like a litany through the book. The restoration of the knot garden becomes Rue’s life’s work, and their dedication to the task, to the growth and care of plants, brings personal restoration.

Margaret Elphinstone is a writer whose novels have journeyed far and wide, in distance and time – from the wilderness territories of Canada in the nineteenth century, to eleventh century Greenland, and back thousands of years to Mesolithic Scotland. Now in her mid-seventies, and having written eight novels and numerous short stories, she didn’t expect to write another; but I’m glad that Rue drew her out of retirement. Elphinstone’s is a distinct voice in Scottish literature, one that I think is undervalued; a quieter voice than some, perhaps, but in a time of crisis, those are often the ones worth paying most attention to.

Lost People is available from Wild Goose Publications (£8.99), and all good bookshops.

Yep; it’s a lovely, bucolic vision. But what it ignores is the complex economic infrastructure on which self-sufficiency and mutualism – and the non-apocalyptic transition towards these – is parasitic and would depend.

Interesting choice of word, ‘parasitic’. Indicative, perhaps, of the distance between your worldview and mine.

I look forward to reading this novel. A quiet voice for mutuality is what I need just now.