Scotland, HS2, Friedrich Engels, and the Multiverse

(I)

As has been widely noted, Angela Rayner recently became the new Michael Matheson in the serial distraction scam through which most of the British media deflect attention from the billions extracted from the public purse to enrich cronies of the Conservative Party.

An article in the Guardian (8 October 2023) speculated that UK losses from fraud associated with the Covid pandemic could be as high as £10.8bn, a mere trifle compared to the £100bn which the Daily Mirror (18 November 2023) claimed had been squandered by the Tory government in four years from 2019. Although other claims noted a similar loss as early as 2022.

The New York Times had much earlier noted the phenomenon: ‘Waste, Negligence and Cronyism: Inside Britain’s Pandemic Spending’, continuing: ‘In the desperate scramble for protective gear and other equipment, politically connected companies reaped billions’ (NYT, 17 December 2020).

HS2, the white elephant whose memory loss is existential, hence no-one remembering what it’s for, or where it’s going, had been estimated to cost up to £67bn (Construction News, 11 January 2024). That is, for its truncated version, London-Crewe: although it was previously announced that it’s not going to Crewe, because the route was further truncated in an October announcement by Rishi Sunak, seemingly the UK prime minister. (Also by coincidence costly and directionless).

Then again, the Westminster government was reported as still buying up property for £1.4m between Birmingham, Crewe and Manchester along a line no longer being built (Observer, 13 April 2024). So with any luck the UK government can still hit the target of £67bn expenditure on HS2, even if the line just goes to Birmingham. Or just tails off, you know, somewhere or other.

Sky News (1 March 2024) reported that the stalled Rwanda asylum scheme could cost £500m, which could buy you a couple of ferries in Scotland and leave change to fund a proper West Coast rail service, that is, if the Tories didn’t keep handing Avanti lucrative contracts.

The cost of the London Crossrail/Elizabeth Line, however, would have paid for so many ferries in Scotland that you could’ve just lined them up end to end, and walked across the decks to the Outer Hebrides, getting useful exercise along the way.

According to the Guardian (again, but do you expect the Scottish or Tory press to cover these things?) at least 10% of donations received by the Conservative Party since 2010 came from those connected with the construction industry, almost £40m. It calculated that housebuilders and property developers benefited by billions of pounds from delays to low-carbon building regulations over only eight years until 2023 (Guardian, 4 October 2023).

Fortunately, Scotland – as we know from Scottish media accounts – exists flexibly both in and also out of the UK, depending on context, in a multiversal fashion which only Professor Jim Al-Khalili can explain.

For example, if the Tory government in Westminster spaffs billions which are also Scottish billions – because Scotland is incontrovertibly British – then, magically, Scotland doesn’t suffer any loss from catastrophic damage to the UK public purse.

That’s: (a) Scotland, part of the UK and all the better for it! And (b) Scotland not part of the UK and none the worse for financial scandals adversely affecting Britain’s economic and social infrastructure. Win-win!

In fact, if not for that £11K iPad business, we’d be able to fix all the potholes.

In this sense, most of what still passes for a Scottish traditional media apparatus can treat Scotland as though it were already independent, while resolutely opposing Scottish independence. (The National, and possibly STV, are among the exceptions.)

For example HS2, from which Scotland will derive no benefit at all, fortunately doesn’t affect Scotland financially either, because the state of the UK budget has nothing to do with Scotland. Because we’re not part of the UK.

Not in this perspective. Only in the other perspective. I hope that’s clear.

(II)

The concept of ideology, at its simplest a way of framing social and political reality, is used in a negative sense when perceived as imprisoning individuals or entire cultures in a false perception of their lives. Scotland, as many including poet Alan Jackson have noted, has an abnormal cultural tendency toward mental conflict and self-doubt (‘O Knox he was a bad man/He split the Scottish mind…’).

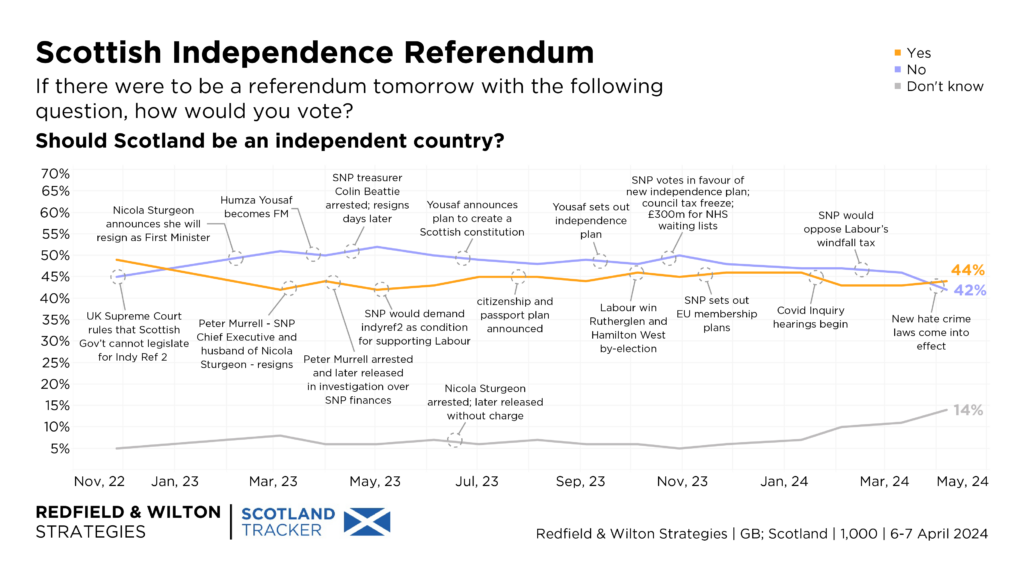

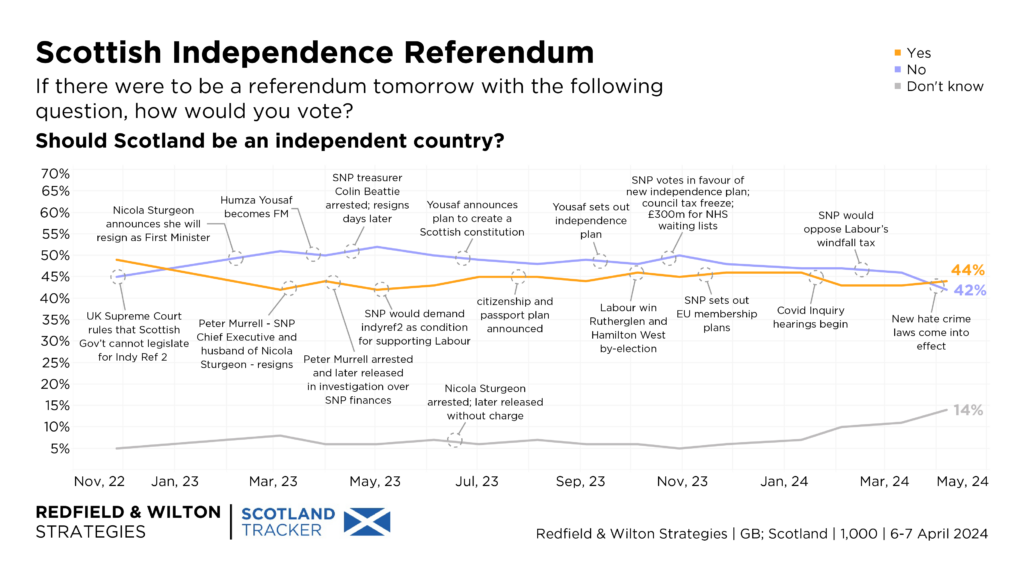

Support for independence is still remarkable at half the population, given this cultural inheritance valuing scepticism or disbelief (‘aye, right’) over commitment; heavily reinforced daily by negative accounts of Scottish life and potentials.

As Friedrich Engels famously observed, ‘All that is real in human history becomes irrational in the process of time, especially if reported in the Scottish media’. (OK, he didn’t actually say that last bit, but he would have, he just didn’t think of it at the time.)

So, out of the EU with no route back excepting independence which still roughly half of us say we don’t want, housing a nuclear base in a world in desperate geopolitical turmoil, defended by Grant Shapps, taxed by Jeremy Hunt, with Nigel Farage and the Reform Party waiting in the wings, the Scots are left to contemplate another Nicola Sturgeon Covid text row (the latest item, at the time of writing, in the serial distraction scam).

Engagement with what we call traditional media has certainly diminished. In ideal terms, of course, the health of Scottish civil society would require precisely the opposite. However, the unregulated nature of press ownership in the UK has left us with a press very far from ideal, and increasingly shorn of basic journalism resource.

The online world is offering alternative voices. But it also popularizes narratives and myths from traditional press sources. Scepticism about Scottish performance and potentials – especially in the economic realm – has become deeply rooted. It wasn’t always so, historically. It’s a construct. It serves particular interests.

Despite these things, and increasingly, as global threats multiply, I suppose we must ask: does Scotland’s situation in any way constitute a crisis worth worrying about?

Given events in the Middle East, Ukraine, the DRC, Haiti and elsewhere, and in the presence of threats from AI, climate, nuclear proliferation and pandemics, life at least for some is relatively acceptable in Scotland. Also less dangerous for all than in some other parts of the world. So if we want to obsess about CalMac’s flaws or the alleged peccadilloes of SNP politicians, that’s our business.

Except for the fact that we don’t. It’s only that interested parties work very hard, all the time, at shrinking the Scottish world.

The historian Timothy Garton Ash a few years into this century described some of the general traits of small nations. Noting the potential virtues of small countries in the EU, he also cautioned that ‘provincialism can be the flipside of modesty’. But he continued: ‘I’ve been thinking about what it is that can enable small countries to think big. One advantage is to have a big past’ (‘What a larger Europe needs is small countries able to think big’, Guardian 3 May 2006).

Scotland is in essence both historically and presently a European nation with a very significant past (both creditable, and like many nations, also not). The Labour Party, to which there are signs of the Scots returning as voters, lives in too much fear of anti-EU sentiment in England even to discuss Europe. Meanwhile under pressure from sources like Reform UK – and even via the unhealthy lure of the MAGA movement in the USA – some English conservatives are moving into an extreme right-wing Twilight Zone, where even Professor Al-Khalili can’t explain the physics.

This doesn’t bode well for either England or Scotland.

The axiom ‘all that is real in human history becomes irrational in the process of time’ was actually intended by Engels as a comment on changing conditions, about judgement over what remains true, or has become outmoded. History is dynamic, for good and bad.

Either way, much better to be part of it rather than spectate, as is our present condition in Scotland. Global threats are all the more reason for small nations to participate in history if they think their contribution can be positive. The influence of small democracies like Ireland and Denmark in the EU is debated, but the more of us there are, the better.

In Scotland we require first to work more seriously at understanding the facts of our economic, social and political existence as a nation. Increasingly, online – which is the source of much distraction from political realities – also offers great potential for political education.

No-one’s going to do it for us, there are vested interests keeping us misinformed, and we’re not as yet remotely capable of thinking collectively about our political situation. But the alternatives look increasingly bleak.

We are raising funds to support our ongoing work – support us HERE.