Anatomy of a Loveless Landside: Labour’s Victory, the Nature of Britain and Post-Democracy

One week ago the UK underwent a quiet kind of revolution. We drew the curtain on years of Tory chaos and psychodrama. A Labour Government was elected with a large overall majority; the Tories won their lowest ever vote in their history; the SNP suffered a significant reverse; while the Lib Dems, Reform and Greens increased their representation and votes.

The UK election was an expression of multi-party politics in voting. It was a very European-style result with five GB-wide parties competing besides SNP and Plaid, along with a host of independents. This was then shoehorned into FPTP to produce majoritarian government with a 172 majority on 34% of the vote, aided by the conventions and codes of the absolutism of the British state and its ancient regime.

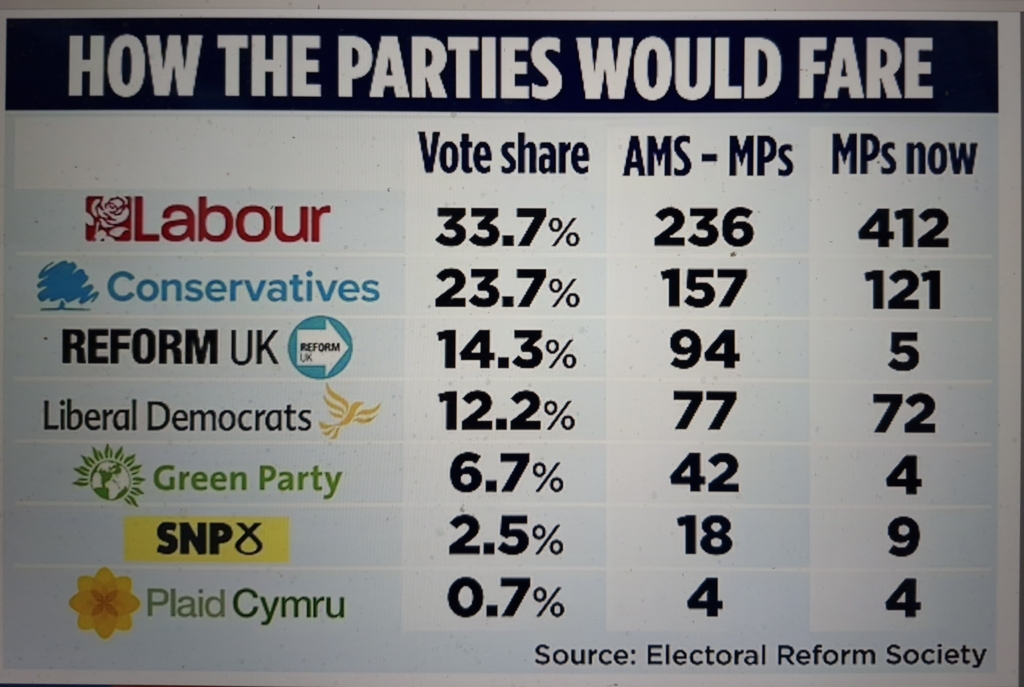

It was the most disproportionate electoral result in UK history, and second in the West, ever – only the French in 1993 exceeding its distortions. Labour needed fewer than 24,000 voters for each MP; Reform UK over 800,000. If the UK House of Commons had been elected under the Scottish Parliament’s system of proportional representation, it would have given Labour 236 (not 411), Tories 157 (not 121), Reform UK 94 (not 5), Lib Dems 77 (not 72), Greens 42 (not 4), SNP 18 (not 9) and Plaid 4 (the figure they got). Labour on the AMS PR system would be 90 short of an overall majority, rather different to the actual majority of 172.

As the dust has settled on the election result, over the next few days I will look at three distinct but over-lapping areas – the overall picture and state of Britain, followed by the SNP and independence. Readers will not agree with every observation and piece of analysis that follows. This is intended to start understanding where the UK, Scotland and independence stand, and start conversations not be an end point.

The election of a Labour Government and the end of the Tory rule is a cause for celebration. This is an opening, an opportunity, a closure and all sorts of other positives. Just because Starmer and Reeves have a limited prospectus (more on which below) does not mean that this historic moment should be dismissed and scorned.

There is a profound difference between how the Labour and Tory parties see the world; it might not be as wide and unambiguous as many of us would want, but it is there. This is how most voters see the world: knowing there is a difference, including Scottish, SNP and independence voters. There is little traction in a left or nationalist miserabilism seen in the likes of The Guardian’s Owen Jones portraying Starmer as a Tory and other inaccuracies; this only takes folk into self-defeating, self-reinforcing bunkers.

Labour’s victory has been called a ‘loveless landslide’ and this is an accurate description. The party won 33.7% of the UK vote, barely up on its 2019 performance (+1.6%). It got 9,731,363 votes, compared to 10,269,051 in 2019 and 12,877,918 in 2017 (the 2015 Cameron victory being the last time that Labour’s vote was lower). These figures are well-known and frequently cited, yet it also true that Labour had a lead over the Tories of nearly three million votes and a 10.0% lead – the latter something it managed only once before in its history, in 1997.

Beyond party support, the UK’s limited and truncated democracy looks even more shaky. Turnout at 60.0% of registered voters was the lowest in post-war times 2001 apart. Approximately 425,000 voters were turned away at polling booths due to Tory voter suppression laws, with BAME voters more than twice as likely to be affected. Add to this the rising number of non-registered voters. Eight million people are now missing from the electoral register, whom are disproportionately younger, poorer and BAME.

The Labour coalition assembled last week has strengths and major weaknesses. The party targeted Tory marginal seats and in doing so, its support in seats and areas it held in 2019 fell. Moreover, Labour support among working class voters has fallen, relative to middle class support and university educated voters. Add to this the fragility in party support with black, Asian and Muslim voters which has been electrified by the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict but is not confined to this.

As Labour in office incur unpopularity, disaffected Labour voters have more choice than in the New Labour era. They can shift to Farage’s Reform, the Greens or the motley crew of independents; or post-2026 the SNP. As Aditya Chaktabortty noted there are already ‘Big cracks in its coalition’ and, when trouble comes, ‘the ground could give way.’

Labour’s limited offer does not address the long-term fundamentals of the British state, government and capitalism. There are no proposals to remake the imperial centre and how it governs and relates to the rest of the UK; no serious plans to disperse and decentralise power, and no initiatives to remake the core institution of economic policy namely the Treasury.

Instead Labour under Rachel Reeves are betting on the chimera of economic growth solving the long-term challenges of the UK and the choices that government has to make. In this Starmer and Reeves have similarities with the rhetoric of Harold Wilson in 1964 who came to office promising modernisation, planning and sweeping away outdated practices to power drive economic growth. Wilson’s agenda with all its shortcomings did take note of the fact that the power of the Treasury – short-termist, micro-managing, about controlling public spending rather than growth – was a roadblock on change, and proposed bypassing it with a new office the Department of Economic Affairs. All this ended in failure and Treasury ascendancy, whereas now all Labour have is mood music and exhortation.

Labour as the party of the union

Across Britain – in Scotland, Wales and England – Labour have become the unambiguous party of the union. It has won across GB in votes for the first time since 2001; it has won England in votes for only the eighth time in its history.

Yet Labour enter office with little real substantive agenda to make real a vision of the union and Britain. The much-cited ‘muscular unionism’ beloved of right-wing Tories is dead for the moment; while old-style Labour unionism which believed in the power of an omnipotent central state and big government doing big things has long gone and cannot be reinvented.

Labour has to now find a new kind of unionism which speaks to the four UK nations, and which does so in respectful language that builds bridges and alliances. Is what could be called a progressive unionism possible? It is not automatically a contradiction in terms; because it depends on what kind of union and politics are being advanced. Is a strategic unionism that emphasises partnership, collaboration and key big-ticket tangibles such as infrastructure development possible?

While such a politics does have obstacles there is a terrain for it to get traction. There is a desire across the UK for central and devolved governments to work more effectively and harmoniously. Add to this the dynamic of a new Labour Government and a tired, exhausted SNP administration which has ran out of road and is now in retreat. Relevant to this is the reality that in the wider SNP and independence community there is a bitterness and jaundice which does not aid an effective, successful politics, and which if it continues to have traction will aid Labour’s room for manoeuvre and taking the initiative.

The English dimension will be a major dimension in all this. David Clark, a former adviser to Labour Foreign Secretary Robin Cook, noted remaining major differences between Scotland and England in the 2024 election. In England the combined Tory/Reform vote was 41.2% whereas in Scotland was 19.7%. This vote, he added, was the main opposition to Labour in England – whereas in Scotland it was the SNP and pro-independence opinion with 34.3%. He stated from this that: ‘Voters in Scotland and England now see the world, and their place in it, in fundamentally different and irreconcilable terms.’

This overstates things. First, the above returns us to the ‘is Scotland different/not different’ indyref debate. The truth is it is not an either/or. Scotland is different from the rest of the UK in some respects, and not different in others. Second, voting behaviour since the 1980s has shown one measurement of difference. But on other measurements, such as Scottish Social Attitudes Surveys, Scotland is not that difference on policy choices. Third, claiming that Scotland is ‘fundamentally different’ plays into a Scottish exceptionalism, while equally claiming Scotland is in no way different is groundless and completely ahistorical. Scotland since its creation has always been defined by a degree of difference and autonomy along with commonalities.

The maximalist difference argument in Scotland overstates the progressive credentials north of the border, ignoring the conservative aspects of Scotland or the limits of its centre-left politics. ‘Scots have been voting social democrat – for want of a better term – for most of a century’ according to Lesley Riddoch in a recent Prospect essay by Bill Kellner of the New York Times.

This is a selective reading of the past, an evoking of collective amnesia, and a debasement of the term ‘social democracy.’ Forty years ago cultural historians embarked on a project – ‘Scotch Myths’ – whose aim was to look at the manifestations of different historical forms of Scottishness and the myths which reinforced them. Maybe in the early 21st century we need to embark on a similar exercise about modern myths, such as the pedigree of ‘progressive Scotland.’

Talking about the British State and British Undemocracy

The nature of the British state and capitalism are central to whether a Labour government succeeds – or not. The Labour Party has long lacked any radical insights with which to understand the DNA of the British state. From the ascent of Fabianism, and the gradualist socialism of the party’s early days, it has believed that the organs of the British state were ‘neutral’ in class terms and could be used to deliver socialism.

Problems with the British state have been long cited in the Scottish debate, but through often invoking a caricature. For example, the condition of the British state and its core problems have little to do with 1707, the nature of the union – or the creation of Great Britain and then the United Kingdom. Rather they are much more deeply-seated and include English parliamentary sovereignty – which George Orwell biographer Bernard Crick called ‘the English ideology’ – and the limits of 1689. Running alongside is the Whig view of history, which became the dominant story of Britain, as the ruling class continued to control the UK’s partial democratisation with the working classes enfranchised politically in a feudal, archaic system.

We are not citizens. We are still strangers in what should be our home. We are subjects invited into someone else’s home conditionally, on the understand that we behave ourselves and do not ask any questions such as how the owners acquired it. This is fundamental to the artifice that is the British political system. Labour, the left, radicals and reformers are all interlopers. At their core they have a sense of doubt and a belief that they are imposters, playing politics to rules and settings created by and for others. Ultimately this comes at a high cost, as there is a need then to change when becoming part of the system that inevitably incorporates and sanitises whoever accepts this mantle.

Scottish voters feel the above even more acutely. Scots are often merely observers at any UK election; not just in votes and seats but increasingly in terms of differing dynamics at play in Scottish and UK politics. This effectively depowers and diminishes the potential power of Scottish voters. But at the same time this powerlessness is a magnified version of the central problem of UK politics concerning its lack of democracy and the reality that the public are not citizens with fundamental rights but mere spectators in a set of rituals created by elites.

This issue of power and collective voice – in the definition of Albert Hirschman – go to the heart of everything about the nature of the UK. The UK is not a modern country. It is not a fully-fledged political democracy, and tragically in terms of government and elites does not see itself or its future as European.

The UK has become a country trapped by the past, or rather an imagined sense of its past, invoked predominantly by the right and reactionaries. Bereft of a plausible, evocative sense of the future, the UK has become increasingly defined by ghosts and memories, and invented and fantasy pasts, filling the space where there should be debate, vision and hope about the future.

Can Labour understand even hesitantly the importance of power, voice and British undemocracy? Can it recognise the prison of that imagined past and articulate a vision of the future connected to real lives and opportunities? The odds are stacked against Labour succeeding, but there is a window of opportunity. It is in the interests of everyone who believes that the current British state is part of the problem that they succeed while understanding the challenges.

The arc of Labour post-1945 is of a succession of electoral victories on a diminishing platform of radicalism and intent – 1945, 1964, 1997 and now 2024. Previously in 1945 and 1964, and to a lesser extent in 1997, there was a pronounced strand of hope, change and belief in a progressive Britain. 2024 is the first Labour triumph shorn of both radicalism, hope and a belief in a different Britain. It is the summary of that previous arc of defeated progressive projects and failure to take on the institutions, privilege and values of ‘the conservative nation’.

Labour under Starmer have come to represent ‘a world without politics – for a legal bureaucratic and managerial mind’ in the words of John Gray in this week’s New Statesman. This is politics as ‘rational administration’ and rule by experts, technocrats, non-elected bodies, judges and judicial review which is the latest manifestation of post-democracy. This is government and politics done by a managerial class believing it knows best. Similarly the SNP in Scotland, traditionally a party of outsiders until recently, became under Nicola Sturgeon a party of post-democracy and technocratic authoritarianism.

This is how politics is increasingly done across the West – where ruling elites want to narrow down the realm of the political, the public realm and democracy and which in an age of disruption and rage will pour petrol on the fuel of populist anger. Added to the mix is the fact that this is all evolving within the landscape of Britain’s undemocracy, absolutist state and truncated electorate, and will be a very bumpy ride which may not end well. Scotland with its own limitations and elites will not be immune from these tensions and their potential shocks.

Post-democracy, born out of the atrophying of mass democracy, reconfiguration of power and wealth, and the rise of a new elite class of finance capitalism, is still shaping the UK and societies across the West. Their future prospectus is not going to be popular, sustainable, or benign, but the forces of resistance are weak, disorganised and for now lacking any serious programme. As long as this disjuncture continues it carries with it huge costs for democracy, government and the rise of an even more rancid politics of the populist and far right.

Labour’s victory may feel like an end of an era, while mainstream media and commentary yearn for the return of ‘the normal’ and even ‘boring’ government and politics. Little of this is going to happen bar it being the end of the Tory era. Politics are going to get more contested, disruptive and messy, as the politics of post-democracy becomes increasingly intolerant and authoritarian. We are living through a crepuscular age: the narrowing of hope and light and coming of an age of darkness where we are going to have to collectively work out our path back into the light.

I’ve a lot of time for Colin Crouch’s concept of ‘post-democracy’, and I agree with Gerry that it now applies to our current political situation. We still have all the institutions of democracy, but they’ve increasingly become formal shells and the political initiative has now passed from the democratic arena and into small circles of politico-economic elites.

However, I’m not sure that we’ve ever lived in a time when things were different. Our nostalgia for a democracy in which the public actively participated in public decision-making under conditions of freedom and equality is more an expression of our social hopes, a future state to which we might work, than a description of times past, of something we have ‘lost’.

Thanks for this. As you stated in your fourth paragraph: “This is intended to start understanding where the UK, Scotland and independence stand, and start conversations not be an end point.”

These are, indeed, uncertain times. Yeats’ poem ‘The Second Coming’ expresses the uncertainty pretty well even though written more than 100 years ago:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The problem for me with regard to the present Labour Party is that they have no narrative, no statement of a vision that encapsulates the kind of place we want to live in that people can grasp easily and assent to. In 1945 Labour presented that and, to an extent it did so in 1964. But from c1978 as a party it seemed to lose any sense of a story (Michael Foot’s romanticism and Jeremy Corbyn, notwithstanding) and to adopt the position that it wanted to run things for a while, just because ……. well….. because they ought to and they are a bit kinder than the ruling class’s vehicle, The Conservative Party. Blair and Brown did effect some significant redistributive policies which improved lives, but they failed to present a hegemony-changing narrative, nor to change the constitution in an equally redistributive way.

Starmer and Reeves and the others have also largely failed to set out such a narrative. Indeed, the speeches and demeanour of Reeves suggests that she broadly agrees with the way the Treasury and financial sector runs things is the only way and the rest of us will just have to accept that.

While these are early days the only positive, for me, have been the meetings with the First Ministers and the English Regional Mayors which showed a degree of respect and offered the possibility of decentralisation and empowerment and opportunities to develop ideas particular to localities.

The Labout Party does so have a vision. That vision clearly expressed in the Party’s constitution and reiterated in every one of its election manifestos.

The Labour Party identifies as a democratic socialist party. It believes that, by the strength of our common endeavour, we achieve more than we can achieve alone in creating the means to realise our full potential both as individuals and as communities.

This vision of strength through unity dovetails with the Labour Party’s unionism and internationalism. The Labour Party was supportive of Scotland remaining in the United Kingdom during the 2014 refereredum and of Britain remaining in the European Union during the 2016 referendum.

It also believes that power, wealth and opportunity should be in the hands of the many, not the few.

The Labour Party’s economic policy reflects Keynesian beliefs in government intervention, taxation to support the redistribution of wealth, and the nationalisation of industry.

Today, there are two distinct wings within the Labour Party. On the right sit those supporters of Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’, who take a more communitarian approach to realising the party’s vision of a socialist Britain. On the left lie the Momentum Group and the supporters of former party leader, Jeremy Corbyn. Compared to New Labour, his latter group support a more traditional, ‘Old Labour’ approach to realising that vision, built around the national (rather than local) ownership of the means of production, greater hostility to the free market economy, and a more aggressive, less meritorious, redistribution of wealth.

This was what Jeremy Corbyn was expressing and it resonated with a large section of the population in 2017, but, not so much in 2019 due largely to the continual monstering of him by the media and the covert sabotaging by the Labour Party establishment.

Starmer, to use his own word, has ‘ruthlessly’ purged the left of the Labour Party. While two wings still exist, the right wing Blairite one is dominant. Although Starmer appeared to support Corbyn when he was leader, and after Corbyn’s resignation, Starmer campaigned to become leader, largely on the principle Corbyn had been espousing. But, on becoming leader these were all discarded, and we are left with the vague ‘pledges’ and Reeves’ acceptance of the current economic theory as were Sunak and Hunt.

As Mr Hassan and others have pointed out, Labour won a huge majority on a share of the vote considerably lower than Corbyn’s and as a fraction of a smaller turnout. The vote was largely ‘to get the Tories out’ rather than a positive endorsement of anything Labour is offering.

We might get some idea at the King’s Speech of what Labour is actually going to do in the first part of this Parliament.

Yes, we will undoubtedly get a better idea of the government’s legislative programme in the next parliament from the King’s Speech; that’s the whole point of the King’s Speech, to announce that programme.

But you were saying that the Labour Party has no clear vision. That’s not true. Its vision is expressed clearly in its constitution and has been reiterated in its successive election manifestos. That vision has remained the same throughout the power struggles between those who seek to realise that vision by communitarian means (‘New Labour’) and those who who seek to realise it by means of a more traditional socialism (‘Old Labour’).

‘mere anarchy is loosed upon the world’

It is difficult to think of a less apposite quotation to describe the recent UK general election.

We had a peaceful election, followed by a similarly peaceful transfer of power.

Better to have no narrative than to have an entirely erroneous one.

Ah, but there’s nothing like a bit of hyperbole, florian!

Colour me sceptical, but I fear this is a strategy not aimed at improving devolution in England (though it may do so), but a mechanism to enable the reduction of devolved parliaments to the level of English councils.

It’s Labour’s policy to enhance the powers local councils in England to the level of the devolved parliaments in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Home rule for Greater Manchester! There’s no hidden agenda to reduce the powers of the Scottish government – unless you know different!

You should read Andy Burnham, Lisa Nandy, and even Gordon Brown on the matter of localism.

Mr Murray will make sure that Holyrood behaves itself !

How?

The prospect of 94 Reform seats is chilling. That would create a dangerous far right bloc. It can feel we are heading that way in that such a scenario confirms the 41% who voted Tory and Reform. No way would Scotland vote for that. Holyrood elections in 2026 need to hold on to the gains we have made.

Jim – I don’t like the thought of 94 Reform seats in Westminster but that would be a fairer representation of their vote. You do not fight Reform by suppressing them you address their highly conflicting policies and proper scrutiny and highlighting their flaws. Look how rising support for Reform stalled after Farage was questioned about Putin and the racism in his party was exposed.

Reform will in all probability get some representation in 2026 Holyrood election because let’s be honest their victim blaming policies will have some traction with right wing people here as well.

What really frightens me in Reform (or some Reform/right wing Tory combo) getting an overall majority in 2029 with 1/3rd of overall vote!

Excellent analysis. Where can one access the source data please?

Many thanks. All the figures, data and references contained in the essay are publicly available.

Britain has many problems but the greatest is its failing economy and rising inequality. The two are related. Looked at from a purely British perspective constitutional politics are not the core issue except that Scottish independence would likely worsen England’s standing in the world and further diminish her economy.

Thank you for a thought-proving article.

The similarity of social attitudes between Scotland and the rest of the UK is often used as an argument against independence. However the fact that social attitudes appear to have such little predictive power in regard of voting behaviour makes me question how informative such measures are about political cultures. Perhaps strength of opinion needs to be factored in? Or perhaps they are just measuring a substrate shared across many European countries. Do social attitudes on these measures differ much between the UK and France or Denmark, for example?

Paddy – the social attitudes line was often trotted out in 2014 to show similarities between Scottish and English electorate. The reality is, as you have stated, is that there are great similarities between social attitudes across many European countries.

The differences between Scottish and English electorate were political (eg support for Tory governments and Brexit.) The last election has rather diminished this argument with both Scotland and England voting Labour as the largest party. This is probably a one off situation due to electoral fatigue with both Westminster and Holyrood governments but it does temporarily undermine one of the main reasons for independence.

The word I looked for, missing in the article and comments so far, is ’emergency’. I would be surprised if Labour’s next projected 5 years in government doesn’t meet with emergency conditions (which may shortly become the norm). And if emergency powers are retained, this presents further challenges to what remains of devolved democracy.

“Emergency powers, which are reserved, allow the UK Government to make special temporary legislation (emergency regulations) as a last resort in the most serious of emergencies where existing legislation is insufficient to ensure a properly effective response. Emergency regulations may make provision of any kind that could be made by an Act of Parliament or by exercise of the Royal Prerogative, so long as such action is needed urgently and is both necessary and proportionate in the circumstances.”

https://ready.scot/how-scotland-prepares/preparing-scotland-guidance/philosophy-principles-structure-and-regulatory/chapter-6-emergency-powers

I haven’t kept up with emergency powers in the UK since looking at civil defence planning for nuclear attacks some years ago, but the British imperial system is unusually vulnerable to autocratic control during emergencies due to its quasi-Constitution and highly centralised political powers under the hereditary theocratic monarch and the Royal prerogatives (surely no-one can describe the incoming PM’s nuclear instructions as ‘democratic’?).

I highly recommend Elaine Scarry’s Thinking in an Emergency to follow this line of questioning. Essentially preparing for emergencies should be the democratic way, whereas without effective preparation you cede decision-making to autocrats. Failure to get into the habits of thinking for ourselves will have predictably bad effects. We should all keep deliberating rather than leave it to politicians and rulers. And when it comes to codifying a constitution, beware of emergency powers clauses.

Yep; I worked in emergency planning in communities in Fife, the Lothians, and the Borders for a number of years, a quarter of a century ago. We used it as a community development tool, working in local action groups to plan and organise in concrete detail the many ways citizens and communities could prepare locally for emergency situations in order to preserve themselves and their autonomy. Many of these voluntary groups were subsequently written into their local authorities’ emergency plans and worked in partnership with the statutory emergency services.