An urban commons in Naples offers a window towards a world beyond prisons

In the courtyard of a self-managed cultural and social space in Naples you can see a wide swath of stars. This is rare in the downtown working class heart of Naples, where the streets are narrow, and there are few open spaces. Economically, Naples suffers acutely from post-industrialisation, austerity and a history where the rich north of Italy has extracted wealth from the south. This community space is a former children’s prison that also offers mutual aid and a social laboratory in participative co-creation and democracy. What has happened to this former juvenile prison not only shows how we can reverse the impoverishment of working class neighbourhoods, it points towards a world without so many prisons.

This building is impressive. The larger of two courtyards is home to a football pitch, hosting Naples’ largest free football academy, basketball training and other sports. It is flanked by self-managed workshops and a popular bar. An archway leads into the smaller courtyard, which is lined with a row of trees. This space is surrounded by doors leading to a free-shop, a communal kitchen, a library and one old prison cell: a remnant of the building’s history. On the second floor there is a gym large enough to practise aerial circus skills, mutual aid rooms for families, classrooms for extracurricular learning, a space for theatre and music performances, pottery rooms and much more. All the things that happen in this building are organised by and for the local community.

Money is no barrier to entry, things are free or on a pay-what-you-can basis. It offers the surrounding community the opportunity to grasp for things that are normally out of reach. Its historical transformation from a brutal children’s prison to a place of community liberation is itself a story of abolition. Furthermore, this self-organised space breaks through the anti-working class narratives that see us as a ‘mob’ that is a danger to the establishment and even to ourselves. Why is there such a high rate of incarceration in most societies? Criminalisation is a self-perpetuating cycle. Structural racism, intertwined with class oppression, are the main causes. What follows focuses on class.

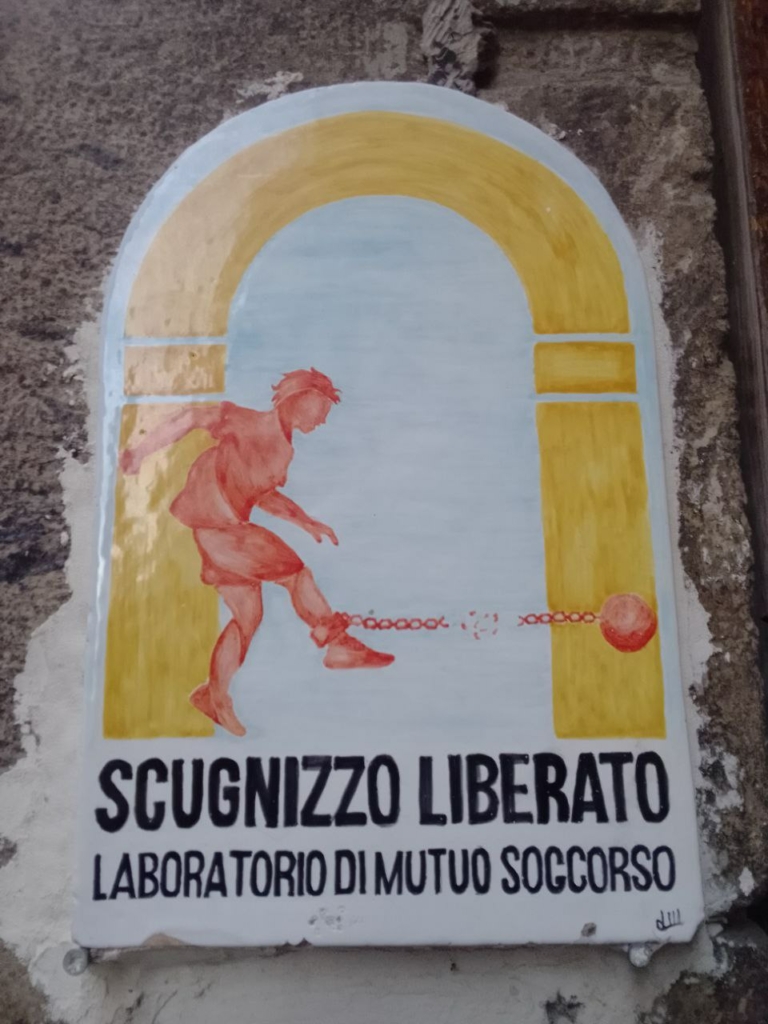

The former children’s prison is now called “Scugnizzo Liberato”, which means ” liberated street child”. It is one of seven grand buildings in Naples that are recognised by local municipal laws as an urban commons. These self-managed buildings are spaces where the local community – and anyone else – can engage and co-organise. The difference from squatted social centres in other European countries is that these buildings are recognised in perpetuity. Naples’ municipal law – the Declaration of Civic and Collective Use – stipulates that these buildings are run by an open assembly and are proactively anti-fascist, anti-sexist and anti-racist.

From prison to abolition

Between the 1860s and 1970s, children and young people were detained in Scugnizzo Liberato, then called the Filangieri Institute. The building has a longer history, dating back to the mid-1500s, as a Capuchin monastery. Whilst it was a prison, local elders warned the children to be good or disappear behind its walls; echoing the threats in old fairy tales about how naughty children can vanish. Law student and participant in the urban commons, Sergio Sciambra, explains the political transformation of the building in his doctoral thesis, which has been invaluable for this article. During its time as youth prison, the building was overcrowded and in poor conditions with around 200-300 inmates.

In the mid-19th century and before, urban populations swelled across the continent as people were displaced from common rural land. The enclosures created wealth for the capitalist elites. To maintain the old social order of feudalism – to keep the working class in check – prisons were built with the auspices of “law and order” and the prison population exploded. In broad strokes, the massive incarceration we live with today began during this period.

Old prison cell

The name Scugnizzo Liberato (liberated street child) refers directly to the building’s past as a prison. In Naples, “Scugnizzo” is a derogatory term for working class youths that is still used today – suggesting they are devious and dangerous. It also translates as “street urchin” or “ragamuffin” or contemporary terms such as “chavs” or “hoodies”, which are used to demonise British youths. Stereotypes against the working class convey power; these are part of a broader attack on the working class as “lawbreakers” who need to be controlled and locked up. Scugnizzo Liberato takes this verbal attack and turns it around. The building’s logo shows a boy kicking a ball with a chain and breaking the chains: the ball becomes a football.

The end of this partcular prison’s story mirrors a form of abolition that became established throughout Europe. Today, youths are no longer imprisoned to the same extent as they were around 100 years ago. For example, the average total population of juvenile prisons in Italy is estimated to be less than 400 in 2022. That is almost the same number that was housed in this one prison at its peaks.

The prison reached a crisis point in the 1970s. Deteriorating conditions led to intense rioting and protests, followed by even more draconian conditions. Although this was not the first crisis, this time things changed. Newspapers reported that the institution was a “snake pit for under-18s”. The inmates’ pressure for change was intensified by political pressure from outside. Under new management, the prison became something else. The focus on punishment and incarceration shifted to education, prevention and re-socialisation of young people. The number of inmates was greatly reduced and at times it became a non-residential space. The institution was at the forefront of a change that went beyond Naples, where young people were no longer simply incarcerated. One example in the prison building is the theatre, a space created by converting former cells.

Naples reclaims the ex-prison

After serving various functions, at the beginning of this century the building lay mostly empty. Plans to renovate the dilapidated building failed. In 2015, Neapolitans occupied the empty building.

“The point of the occupation was to give this building back to the district, because it is huge and wasn’t being used for anything,” explains Roberto Sciarelli, an organiser involved in the urban commons. “You have to imagine this place as a huge ruin with people working and doing tasks like clearing invasive plants, removing trash, cleaning everything, restoring the water system, restoring light, all the things that are necessary to make this place habitable and accessible. It was a lot of work.”

Football academy

Locals and others first renovated the theatre, as many musicians, actors and other local artists had few spaces to work and collaborate in. Then attention went to the gym, the ground floor and first floors. Renovation works are still planned for the second, third and fourth floors.

Scugnizzo Liberato holds its weekly assembly on Saturdays. Sciarelli told me that in the earlier days, people with university backgrounds, who were often more self-confident and privileged, tended to speak more at the assemblies. However, the culture of the assembly consciously evolved to elevate the voices of the working class by thinking about care in the broadest sense.

“The community listens much more to people who have demonstrated their commitment and care for the community. Creating a culture where physical labour, caring, and repair are highly valued really helps with horizontality. The assembly enables different people with different expertise and experience to be themselves and have their voices heard.”

Elevating working class voices through participative democracy is at odds with the status quo. In liberal democracy, most politicians – aka “lawmakers” – are disproportionately drawn from the middle and upper classes. This situation is reinforced by the image of the working class defined as a mob, and lawbreakers – which helps to explains why it is acceptable that so many working class people are in prison.

Creating space for self-employment in the workshops is another function of the urban commons. An ex-offender has set up an upcycling business. An umemployed woman has set up an affordable bar and cafe. All of Scugnizzo Liberato’s self-employed people do not pay rent, instead contribute to the management or care of the space and offer training in skills, from making stained glass windows to building skateboard ramps.

Participants value the commons for various reasons. Sciarelli explains that it is literally a place that they have built. Marta Giardinelli, who helps organise the mutual aid for children, says: “It’s a resource that is constantly evolving, and it’s a safe place where everyone [from different social backgrounds] gets to knows each other, which is quite difficult in a big city.”

Joss Vincent runs the English help desk that responds to what help people want, from academic needs to basic conversation practice. I speak to her after a childrens’ book’s launch in one of the rooms for mutual aid for families. She explains: “We want it to be an important space, because there is very little here. There are no open spaces in this part of the city. There are very few community facilities, and the private ones are too expensive for most people.”

In the theatre I meet three local students who are rehearsing a play in another language: Neapolitan. Law student Giada Laporta explains how important the space is, as it offers things that the city council cannot afford: “This is a cultural laboratory. We provide a kind of instruments and tools for these kinds of activities that should be accessible to adults and young people. This place is important because we can make art here for young and old people, without any boundaries.”

Nursery space

Raffaelle Cissone, who is also rehearsing the play, tells me how Neapolitan language is often mocked across Italy, because it is predominantly a working class language. For him, it is important to be able to perform in his mother tongue: “We can speak from the heart in our language. We are glad that our city has this tradition, not only in theatre, but also in literature, music and other arts. We try to maintain it and make our identity strong.”

It is powerful to hear young people freeing themselves in a room where they were once locked up. Nearby, a dozen teenagers attend a pottery class, and the urban commons will mean something different to all of them. I hear that former inmates and older people from the local community often come into the space, and I can not imagine what its transformation means to them.

Going further, thinking towards a horizon of abolition, where mass incarceration is not the norm, one lesson about Scugnizzo Liberato is that we do not just need to break through the physical structures that underpin this system. We must – and can – rethink the socially constructed power structures that constrain us. We must denounce classist and self-fulfilling ideas, not least those that consider the working class unruly and dangerous. Instead, if we elevate the multitude we can co-create a completely different future together.

Marvelous. The kind of article that makes me wish I were wealthy–so I could support this exceptional publication/site.

What a brilliant initiative ! Would be great if we could replicate something like this in Glasgow, say. Thanks so much for sharing.

When I worked in the Nordics they had residential prisons. Non violent prisoners were housed in these places still working in the day but required to spend Al, other time at the residence. This might reduce costs abd take load off prisons in UK.

Thanks for sharing an inspiring story about the power of the commons. So much more human than the current system of oppression / fear of ‘the masses’ by the few. Has to be the way of the future if not easily won.

Superb article and uplifting . Let’s see something like this in Scotland

How many children were locked up in Italy because they reported sexual abuse by priests and other adults? Italy has been called an anomaly because it is has been so far behind other nations in addressing clerical abuse, and apparently been recently criticised by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child for its safeguarding failures. We’re still seeing high-ranking officials arrested, right?

I don’t see how you are going to address the recruitment of youngsters into fascism until you properly expose the appalling wrongs done to children by the authorities, and bring whatever measures of justice and reparation you can to them.

‘Criminalization is a self-perpetuating cycle. Structural racism, intertwined with class oppression, are the main causes.’

What is the evidence for this; particularly the assertion about racism ?

Peter Santenello visits this on his youtube-channel when he is visiting Naples. “Inside Italys craziest city- Naples”. A great video.