Early encounters with the radical right

1964 was the last time that both a British General Election and an American presidential election took place in the same year. The Labour Party was then attempting to end almost 14 years of Conservative rule, while in the US, the Republican Party candidate with a “special and dangerous view of the world” had shifted his party firmly to the right. I’m certainly not the first to spot the parallels. What can the political literature of 60 years ago tell us?

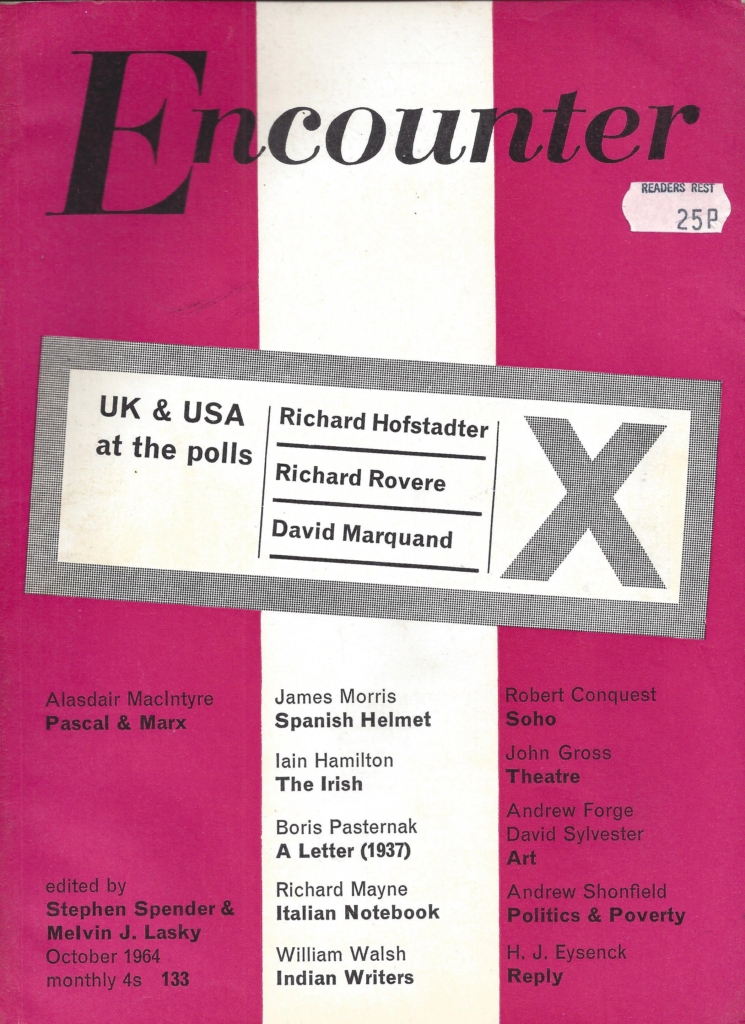

I recently found myself reading a yellowing copy of Encounter magazine from October 1964. In it, three leading commentators- Richard Hofstadter, Richard Rovere, and David Marquand – discussed the forthcoming elections. There were striking parallels. In particular, Hofstadter and Marquand had much to say which has relevance to today’s radical right and its chances of reshaping our politics.

In 1964, the rise of the radical right was making itself felt. Though Barry Goldwater would be heavily defeated in 1964, his brand of politics would eventually come to dominate the Republican Party under one of his main cheerleaders, Ronald Reagan. In the UK, Enoch Powell and other ‘anti-collectivists’ of the right were coming to prominence. These ideas would later form the basis of the Hayekian New Right and Thatcherism. Such ideas have come to define much of contemporary British conservatism.

A fascinating relic

One interesting aspect is the location of these articles; Encounter magazine. Encounter is a fascinating relic of the Cold War. As early as 1968, it was revealed that much of the funding for the magazine came through a front organisation of the CIA, the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Figures such as Malcolm Muggeridge were involved in setting it up and ensuring that it had a distinctive Anglo-American character.

Encounter was, as Frances Stonor Saunders has put it in her book of that title, an important part of the Cultural Cold War. (published in the UK as Who Paid the Piper?). Despite its murky funding, there was little doubt that Encounter was a significant publication, featuring within its pages many of the most prominent public intellectuals of its era; particularly in its heyday in the 1950s – 1970s. Hofstadter and Marquand were good examples of this.

One of Encounter’s aims was to draw the European left away from Marxism. A key contributor to Encounter was Leszek Kołakowski, author of several critical analyses of Marxist thought. Kołakowski was an important influence on centre-left figures, such as Tony Judt and Timothy Snyder (Kołakowski features prominently in Snyder’s On Freedom).

The Paranoid Style

Richard Hofstadter was one of the most interesting commentators on the radical right in America during the mid part of the 20th century. Though a critic of the radical right, his fundamental approach was to try and work out why its supporters believed what they did.

His 1964 essay and book The Paranoid Style in American Politics is of great relevance to the conspiratorial aspect of the hard right, as expressed by media figures such as Tucker Carlson and, indeed, Trump himself. As Hofstadter put it, ‘American politics has often been an arena for angry minds’. Hofstadter’s musings on the politics of resentment, the power of conspiracy theories, and hostility directed at intellectuals (discussed in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life) seem highly relevant.

Hofstadter was alarmed by the Goldwater campaign which crystallised trends he’d become concerned about. His concerns echo those previously expressed in in Encounter by Brian Crozier. In a 1962 article ‘Down among the Rightists’, Crozier examined the influence of the ‘lunatic fringe’ of ‘right-wing extremism’ and its influence on American conservative politics. Interestingly, Crozier went on to become a key figure on the ‘anti-Marxist right’ in the UK 1n the 1970s.

For Hofstadter, Goldwater’s rise had revealed ‘how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority.’ Hofstadter presciently saw the coming of the ‘liberal elite’ thesis which is central to the hard right. In contrast to previous forms of conservatism, which defended the establishment, ‘the modern radical right finds conspiracy to be betrayal from on high.’ This shift is absolutely critical in understanding the changing character of conservatism.

The hard right tends to portray itself as a marginalised group. This aspect of conservatism has been present for some time. Writing in 1979, Andrew Gamble noted that many conservatives had ‘transformed from natural defenders of British institutions into frequent outsiders and critics.’ This tendency has strengthened in the decades since.

In his 1964 Encounter essay ‘Goldwater and His Party: The True Believer and the Radical Right’, Hofstadter related that Goldwater had ‘altered the character of the party’ by ‘committing it firmly to an ideology’. He concludes by saying that ‘if he is successful, whether elected or not, in consolidating this party coup, he will have brought about a realignment of the parties that will put the democratic process in this country into jeopardy’. Goldwater was unsuccessful electorally but set in train changes with the Republican Party. The hard right movement conservative, is the heir of Goldwater, the self-proclaimed Conscience of a Conservative.

Centrist concerns

Hofstadter’s position as an American liberal is in line with the general line of Encounter, concerned about political extremism of the left and right.

A regular contributor (21 articles) to Encounter was David Marquand, who became one of those profoundly concerned about the leftward drift of the Labour Party in the 1970s & early 1980s under the influence of its “lunatic fringe” – becoming a prominent member of the SDP as Roy Jenkins’ right-hand man. He later became, according to Anthony Barnett, “arguably the most important thinker, polemicist, and theorist of the democratic left in Britain during a crucial period between Margaret Thatcher’s election victory in 1987 and David Cameron’s in 2015”. Key aspects of his analysis of the hard right are present in his early essays.

Marquand’s commentary piece in the same edition, ‘Battle of the Ghosts’, is also packed with stark contemporary relevance. It provides a neat summation of concerns, from a social democratic perspective, about the radical right in the UK. Marquand picks up on what would become a central theme of a significant and influential portion of British right; the shift towards Hayekian ideas.

The soul of British Conservatism

Marquand talks of the way that the Conservative party had historically steered its way through social and economic change. While it had generally been ‘the principal political instrument of the rich and powerful’, the Conservatives had ‘never identified itself wholly and exclusively with the capitalist system and the law of the market’. Equally, while it had ‘resisted the coming of the welfare state’ the party ‘was reconciled to its defeat with comparative good grace’. In short, it had successfully adapted to the new reality. However, not all within the conservative movement were happy with this.

Marquand was comparing this with the perspective outlined in a collection of essays, Rebirth of Britain, edited by Arthur Seldon. In an advert in the same edition, the book was described as a call for ‘a greater emphasis on individual enterprise and less power for the bureaucrats and planners’. Seldon was to become one of the central figures in the British New Right, through the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Marquand was not convinced by the description of the collection as ‘non-partisan’. For Marquand, the views expressed in the symposium ‘were totally opposed to those of the Labour Party’. Their only relevance was the degree to which ‘they may be taken up by the Conservative Party’. What they contained was a particular view of the world, focused on the revival of free markets, ‘not in the least peripheral to the submerged struggle for ideological victory which has been going on inside the Conservative Party’. What the tendency was aiming to do constituted ‘a takeover bid for the soul of British Conservatism’. A central figure in this ‘attempt’ was Enoch Powell, which was adding ‘political spice to the attempt’. This was even in the early 1960s, before his notorious interventions on the subjects of race and immigration.

According to Marquand, Powell ‘had an intellectual passion rarely seen in British politics and almost never in Conservative politics’. This is echoed by the contemporary hard right which wants to win the battle of ideas as a precursor to winning political victory. This desire is seen in the veneration of figures such as Roger Scruton who has, since his death, become a lodestar for the hard right.

For Marquand, Powell had ‘shone a harsh and glaring spotlight on the internal conflicts and tensions of modern British Conservatism’. Above all the radical right, including Powell, were critics of ‘Tory collectivism’. Such a view is echoed today by the likes of Nigel Farage and Richard Tice who claim that the Conservatives have become essentially a social democratic party, and CINO (Conservative in name only). In short, the hard right wishes to delegitimise the centre-right, arguing that only they represent ‘real conservatism’.

Marquand ends by looking forward to what might happen post-election. He suggests that ‘if the Conservative Party loses the election by substantial margin, it seems to me to be quite possible that the doctrines put forward by Powell and his colleagues may provide the rationale for its opposition to the next Labour government’. In short, a switch to the radical right is very possible. For Marquand, it was clear that the party might ‘succumb’ to such a mode of politics: “the Rebirth of Britain could yet become the manifesto for the British equivalent of Senator Goldwater’s movement in the United States”.

Marquand felt that the conservative party’s ‘ power structure’ was ‘tighter and more hierarchical’ than, for instance, the Republican Party. This meant that a radical right takeover was, ultimately, unlikely. That the Conservatives might take such a radical step to the right has long been articulated by analysts of the British right, such as Andrew Gamble.

As has been evident in his subsequent work, Marquand believed that such a politics was riven by contradictions and fundamentally wrong in its diagnosis of Britain’s problems and its proposed solutions. He became one of the most prominent critics of Thatcherism (in The Unprincipled Society, 1988) and its deleterious effects on the public domain (The Decline of the Public 2004). Writing in a 1996 essay ‘Moralists and Hedonists’, Marquand argued that the market is ‘inherently amoral, antinomian’ and ‘subversive of all values except the values of free exchange’, and therefore the ‘New Right’s moral vision was…at odds with its economic vision’. It was this contradiction that helped explained the ‘disarray’ of contemporary Conservatism.

That the hard right is the coming thing in British Conservatism has been widely articulated. It was widely assumed that the party would fully embrace hard right politics in the wake of a General Election defeat in 2024. That the final two in the leadership contest were Robert Jenrick and Kemi Badenoch seems to support this. Crucially, this view has been articulated by both opponents and supporters of the hard right. For its critics, it’s evidence that the Tories have ‘lost it’. That increasingly embracing such a brand of politics is evidence that they are no longer fit to govern. That, the party is, following an electoral defeat, indulging in self-immolation.

Deep echoes

What is significant is the way in which their concerns about the radical right is echoed in our contemporary politics. The contemporary hard right can be seen as a blend of the two strands of politics that so concerned Hofstadter and Marquand. In short, a politics which draws on aspects outwith the mainstream of conservatism. It’s a brand of thinking that is millenarian in character, not a politics of preservation.

In some ways the two views also manifest a certain liberal consensus. This is the idea that the radical right poses a serious threat to democratic norms. It’s even expressed by people who would have been considered fairly right wing in previous eras. Figures such as ‘never Trumper’ Republicans such as Bill Kristol, for whom Trumpism is something of an infection in the Republican Party. Similarly in the UK, figures such as Rory Stewart embody a strand of conservatism that sees the hard right as illegitimate as not proper conservatism, just very right wing. .

Hofstadter and Marquand’s view is that the radical right is dangerous but also incoherent. Such critiques by senior figures in academia only feeds the hard right narrative of an arrogant liberal elite. Hofstadter certainly seems to fit the image as a patrician figure, looking at the radical right and its supporters with some scorn. Marquand also embodies a number of characteristics targeted by the hard right.

He was close to Roy Jenkins, seen by some social conservatives (such as Peter Hitchens)as having helped inaugurate hyper social liberalism. As with Jenkins, Marquand shared a strong devotion to the European dream, believing that the UK should play a central role within it. Marquand also held senior positions at Russell Group universities, including a spell as principal of an Oxford college (Mansfield). Just the type of figure critiqued by the likes of Matthew Goodwin.

Particularly in Hofstadter’s case, there’s a sense that the radical right feeds off a fundamentally anti-intellectual view of the world. This again feeds into the liberal elite thesis. Marquand certainly saw Brexit as an intellectually incoherent idea. But, in the right hands, incoherent ideas can prove popular and shift the political dial.

The cult of personality

Hofstadter was clear that the limitations of Goldwater as a leader undermined the electoral chances of his movement. In a later Encounter essay (‘The Goldwater Debacle’), Hofstadter talked of the “gross ineptitude” of Goldwater’s campaign. According to Richard Revere in his ‘American Letter’ in the same edition of Encounter, Goldwater was “not a theorist, not an organiser, not even, really, much of a leader”. Political movements wanting to break the mould needed dynamic leadership delivered by people who could reach out beyond the traditional constituencies. This is why Trump very much fits Hofstadter’s analysis.

There was little doubt that, though easily ridiculed, Trump is a very effective performer. Saying that what is inconsistent and sometimes incoherent is not enough to undermine him. He has formed a loyal following, which supports his MAGA movement with cultish intensity. In ‘The Goldwater Debacle’, Hofstadter talked of the “Goldwater cultists” attempting to take over the party.

That Trump is dangerously effective is expressed by one of his most prominent conservative critics, Bill Kristol. Kristol is the son of Irving Kristol, often dubbed the ‘godfather of neoconservatism’. Irving Kristol was also, interestingly, one of the founding editors of Encounter. For Bill Kristol, Trump is “easy to mock” but actually “a very skilful demagogue” who adeptly “reads the crowd”. It’s now clear that Trump is no passing fad but that “Trumpism is a deep strain in the body politic”.

However, argues Kristol, Trump himself is crucial to this; it’s only him which makes this agenda popular. He cites the efforts by Ron Desantis to echo Trumpian themes, especially in relation to culture war issues (“We will fight the woke”). However, his attempts to emulate Trump have been unsuccessful so far.

Immediately, we think back to Goldwater’s ability to build a strong movement within the Republican Party, win the Republican nomination, but then his total failure to connect to the wider electorate. Again this suggests that the radical right needs good leaders- as is true of all political movements.

This question of leadership is something which confronts the British hard right. It is certainly a powerful strand within the British conservative movement but who is going to lead it? In terms of someone who has elements of Trump in his style and approach is obviously Farage. Again, there must be deep doubts about how wide his appeal really is. There’s no doubt that he is seen as a conceivable Prime Minister by a portion of the electorate, but how widely held is this view?

Farage is certainly an effective campaigner and media performer- and is good at turning ‘mainstream media’ performances into opportunities to bash the typical targets. Take for example his clash with Andrew Marr several years ago. He got riled up and lashed out at the BBC (“What is wrong with the BBC”, “this is absolutely ludicrous”). In so doing he was building on a strong narrative within the hard right; that the BBC no longer represents the views of the general public but instead represents an elite orthodoxy. The performance was, inevitably, seen as somewhat ludicrous by many but praised by many on the right who are also heartily sick of the BBC and the values it’s now seen to represent. A hard right narrative built over decades and now a secure part of our public discourse.

Hibernation

Hofstadter and Marquand’s work has stood the test of time. Hofstadter’s work remains widely cited, in particular in relation to the role of conspiracism in American conservatism; QAnon, Trump etc. Marquand’s work, such as that on social democracy and the impact of the free market on the public domain, has been influential.

What their 1964 essays in Encounter demonstrate is that political parties contain particular strands and traditions which jockey for position over the years. None of them really die, they might just hibernate. Hofstadter and Marquand may have hoped that (what they consider) the incoherence of hard right ideas may have caused this ideology to become extinct.

That’s far from the case.

I’m not familiar with events of 1964, and the closest I’ve come to the CIA-backed writers of Encounter was reading Frances Stonor Saunders’ book, but I do know that culture war historians have drawn attention to the fact that the lavishly-funding CIA was hypocritical in its attitude to the free market (buying up tons of the books of treasonous-mercenary poets on its payroll, for example), just as Conservatives were historically hypocritical about switching support to and from free markets and protectionism as it suited their own interests (not for ideology as they professed).

In fact, it took relatively tiny sums to corrupt many writers, academics, trade unionists etc in the post-WW2 years. And as mathematical models have apparently proved, just small advantages can grow exponentially over time, especially if considering who gets posts, published or preferential treatment.

Having recently read Spy Schools: How the CIA, FBI, and Foreign Intelligence Secretly Exploit America’s Universities by Daniel Golden (2017), I have looked in vain for a British version. Our spooks may be superficially more open these days, but all the biases of the last century must accrue in certain directions, like iron filings in a magnetic field:

https://careers.ed.ac.uk/students/undergraduates/discover-what-s-out-there/find-out-about-types-of-jobs-and-employers/exploring-jobs-and-sectors/popular-sectors/government-social-research-public-protection/intelligence-security

If you block discussion of your foe’s ideology, if you cheat by illegally blockading and sabotaging your rival’s economic model, if you bribe and lie to your allies, if your official history is a self-serving myth, if your society is based on unearned privilege and despises fairness, if your hatred of foreigners is so great you overthrow democratic governments around the globe, what have you got to offer the world?