Korean Dispatch

Jamie Maxwell reports from Seoul.

I arrived in Seoul on 15 January, the day the president was arrested. Armed police had to scale the walls of his compound and force their way past a cluster of private security guards. These events were broadcast live on TV. On 18 January, a judge extended Yoon Suk Yeol’s detention order: under questioning, the president had stonewalled investigators. Hours later, after nightfall, hundreds of protesters – Yoon loyalists – stormed Seoul’s Western District Court, an administrative building located just south of the Han River. Windows were smashed. Furniture was destroyed. By the time the authorities had regained control, several dozen rioters had been taken into custody.

January’s convulsions had been brewing for a while. On 3 December, Yoon made the shocking and apparently premeditated decision to impose martial law. The decision was quickly rescinded: Yoon misjudged the scale of public opposition to, and military enthusiasm for, a coup. But the damage had already been done. On 14 December, Yoon – a former anti-corruption prosecutor turned bristly rightwing populist – was impeached by South Korea’s national assembly. The 64-year-old will soon stand trial for insurrection. If found guilty, one of two sentences – life imprisonment or death – awaits. (It won’t be death: South Korea hasn’t executed anyone for years.) Yoon denies the charges against him and describes his detention as illegitimate. Indeed, he believes he is the victim of a plot; a vast leftwing conspiracy orchestrated by opposition politicians, the courts, North Korea, and the Chinese state.

Yoon’s paranoia is real, deep, and radial. On the morning of 18 January, I emerged from Gwanghwamun metro station into a mass gathering of South Korea’s insurgent conservative movement – the unruly rank-and-file of Yoon’s support. The gathering stretched for at least a mile along Sejong-daero, a sprawling civic boulevard that runs through the centre of Seoul. Upon exiting the station, I encountered protesters carrying American flags and placards emblazoned with the words ‘STOP THE STEAL’ in bright blue print. On the pavement, there were stalls. On one of the stalls sat a laminated picture of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. When I asked the lady running the stall if she liked Gramsci or not – in retrospect, quite a stupid question – she formed her index fingers into a cross and replied in English, “No.” I smiled at her awkwardly and moved on.

This, I realised, was a meeting of the alt, or radical, or pan-national right. In addition to American flags, I saw Japanese and Israeli insignia, signs that read ‘CCP’ – Chinese Communist Party – ‘OUT’, and men huddled in MAGA hats bearing the modified injunction to ‘Make Korea Free Again.’ I struck up a conversation with an elderly attendee. (All the attendees were elderly.) Gee Chai-sung was an academic at a local university. He thought the left had rigged South Korea’s most recent assembly election, held in April 2024. “Donald Trump was defrauded and lost his presidency,” he told me. “And it’s the same here: the opposition is under the influence of North Korea and the CCP.” What would you like to happen next, I asked. “America should support our free democratic nation,” Mr Gee said.

On the other side of Gwanghwamun station, at the far end of the boulevard, a counter-demonstration was taking place. Palestinian colours replaced those of Israel and America; a band played rock songs from a stage at the side of the street. I approached a small group of activists. They turned out to be members of the Korean Labor Party (KLP), a tiny socialist faction without representation in the national assembly. Su Chung Lee was an engineering student in his early twenties. He wore a red tabard embossed with a white rose – the political imprint of the KLP – and, in his left hand, clutched a banner calling for trans rights. Su Chung Lee told me that Yoon’s actions amounted to an “illegal coup d’état”, an assault on the constitutional fabric of South Korean society. Some conservatives want Washington to intervene directly in Korean politics, I said. Does that make you nervous? “I am seriously concerned about [the return of] President Trump,” Su Chung Lee said.

How did South Korea, otherwise known as one of the most vibrant democracies in East Asia, get into this mess? The short answer is that Yoon had been stirring up hysteria among his supporters since he was elected, by a single percentage point, in the spring of 2022. He ran on an anti-woke ticket, pledging as one of his first acts to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, a government department established in 2010 to advocate on behalf of women and minority groups. (The Ministry had to go, Yoon said, because it “treated men like “potential sex criminals.”) In 2023, during a set-piece presidential speech, Yoon claimed that South Korea faced a constant threat from “totalitarian forces” – forces that wanted to wrench the country away from its strategic alliance with Japan and the US.

For Yoon’s base – a profoundly male cocktail of Evangelical Christians, vaccine sceptics, YouTube obsessives, and pensioners misty-eyed for the era of post-war authoritarian rule – this rhetoric was exhilarating. South Korea was already in the midst of a frenzy against feminism and the cultural left when Yoon was elected three years ago. So, on 3 December, when he announced that “North Korean communists” and “anti-state” elements had infiltrated the legislative assembly, and that martial law was necessary to rescue the Republic from “falling into ruin”, his acolytes jumped instantly to his defence.

The putsch, of course, was a disaster. Senior members of Yoon’s cabinet privately warned against it. Some of the soldiers sent to pacify the assembly building refused to restrain opposition MPs. Others loaded their weapons with empty cartridges. Still, Yoon’s decree marked the first time South Koreans had experienced martial law since the army, operating under the orders of General Chun Doo-hwan, had seized power in 1980 – and the first time their political institutions had been suspended since the end of Chun’s regime eight years later. South Korea has weathered various crises over the past four decades: the Asian Financial Crash of 1997, heightened nuclear tensions with the North, the impeachment of another conservative president, Park Geun-hye, in 2016. Never has its incipient democratic system endured such a sudden and dramatic split.

Korea’s relationship with the US is complicated. During the Korean War (1950 – 1953), American planes dropped half a million tons of munitions, and 30,000 tons of napalm, on communist targets in the North, making North Korea one of the most heavily bombed countries in the history of modern warfare. (Also on this list, not unrelatedly: Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos.) Today, the US has some 28,000 troops stationed on South Korean soil, plus naval bases in Busan and Jinhae. In theory, South Korea doesn’t need America’s permission to defend itself from foreign attack. In practice, if Kim Jong-un launched an assault on Seoul tomorrow, operational control of Southern forces would fall to Xavier T. Brunson, a four-star general from Fayetteville, North Carolina, whose bosses work at the Pentagon. On questions of national security, South Korea isn’t really an independent state. It is an American military protectorate, a boundary position for US interests in the Asian Pacific.

Given the obvious ideological overlap between the two men, could Trump use his leverage to demand Yoon’s release? That seems unlikely. Trump’s instincts are too transactional, too crudely isolationist, for him to care about the fate of a failed South Korean caudillo. Equally, democratic reform on the Korean Peninsula has never been an American priority. Between 1960 and 1988, South Korea was run by a series of strongmen: Syngman Rhee, Park Chung Hee, and Chun Doo-hwan. Each one received extensive support from Washington on Cold War, anti-communist grounds.

Yoon’s political authority has been terminally fractured, but he could yet be freed. South Korea’s Constitutional Court still has to rule on the validity of the national assembly’s impeachment vote. Its judgement is expected this week. In advance of the ruling, the Seoul Metropolitan Police have been stockpiling batons and pepper spray and may close down metro stops close to the Court building on the day. The raucous congregation of the alt-right I encountered in Gwanghwamun (its leftist counterpart was more subdued) was one of many such mobilisations to have taken place this year. Yoon’s insurrection trial, a separate criminal proceeding, will commence in April or May.

Yoon himself remains unbowed. Speaking in court in February, he once again claimed that anti-state actors – North Korean or Chinese or Marxist or woke subversives – posed an “existential threat” to South Korea’s sovereignty. The claim was characteristically nebulous and unsubstantiated. A sizeable minority of South Koreans nonetheless believe it. Two-thirds of Yoon’s supporters think the liberal opposition Democratic Party is guilty of electoral fraud. Twenty-eight per cent of South Korean voters want Yoon’s presidency reinstated. Forty-eight per cent of citizens over the age of 70 think his martial law decree was justified.

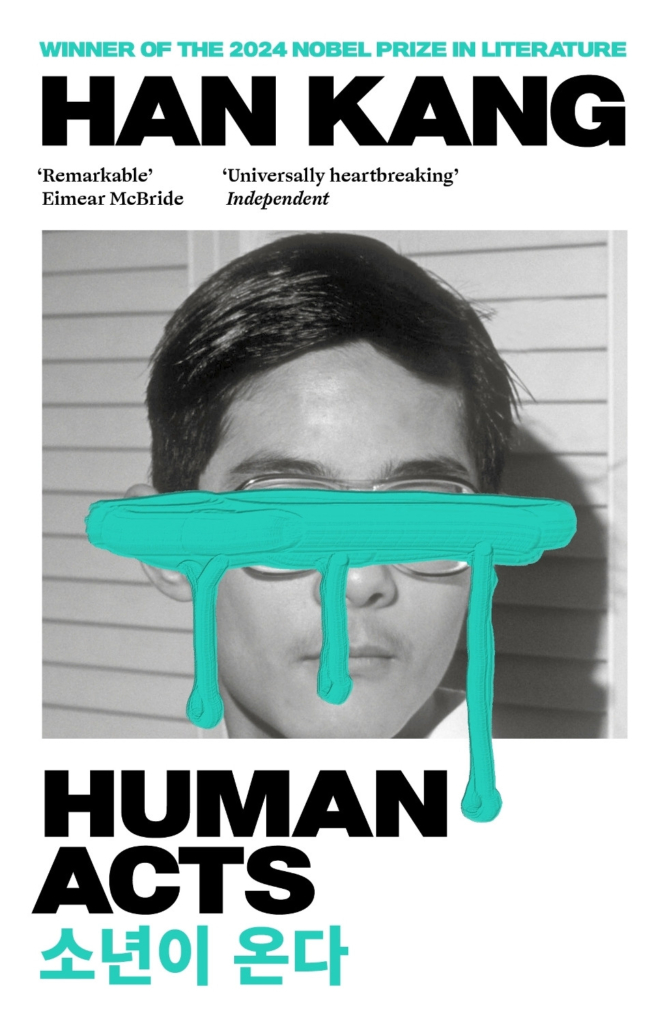

In an interview with The Guardian in 2020, shortly after the release of his Oscar-and-Palme d’Or-winning film Parasite, the South Korean director Bong Joon-ho reflected on the unsettled social dynamics of his home nation. “On the surface, it seems like a very rich and glamorous country, with K-pop, high-speed internet, and IT technology,” Bong said. Beneath the gloss, however, South Koreans feel “a lot of despair.” The writer Han Kang – the recipient of last year’s Nobel Prize for Literature; South Korea’s first such awardee – has made similar observations. Kang’s novels are short, violent shots of narrative. Her 2014 book, Human Acts, follows the events leading up to and during the Gwangju massacre: the infamous killing by Chun Doo-hwan’s forces of more than 2000 pro-democracy campaigners, most of them students, in the summer of 1980. “[My work deals] with heavy and painful things,” Kang remarked recently. A lot of despair. Heavy and painful things. I wouldn’t be surprised if South Korea’s problems were just kicking in.

Image credit: Jamie Maxwell

This article was first published in The National, republished here with thanks.

Please donate & share:

Backing Bella Caledonia 2025 – a Creative & Arts crowdfunding project

remember each time you pay a dentist that dentistry was free on the NHS until charges were imposed to pay to re-arm for the Korean war.

The poor and disabled are now being charged for proposed intervention in Ukraine. ” Plus ca change”

Although apparently Yoon Suk Yeol is a Catholic, not an evangelical Protestant.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoon_Suk_Yeol

To what extent does Christianity, and its historical regional role as footsoldiers of colonial corporations and Empire, play a modern political role in South Korea? Have its Presidents always been USAmerican puppets? Of course, there are militant, right-wing, intolerant versions of Buddhism (and other religions) too. Is atheism seen as unpatriotic?

When I last looked at the figures, there appeared to be a large amount of emigration from South Korea, as graduates struggled to get jobs and increasing numbers of vulnerable people lacked a social security net to save them from destitution and despair (sounds familiar), undermining the cultural norms of caring for elderly and infirm family members.

If it is the case that some restrictions on foreign immigration have been lifted to provide some balance, this presumably feeds into the political discourse there.

Two things I remember from economist Ha-Joon Chang’s book 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/23_Things_They_Don't_Tell_You_About_Capitalism

is that South Korea’s ‘tiger’ economy was based on much state intervention and lots of (stable) regulation. That would put their history very much at odds with Trumpism or (‘red tape slashing’) Starmerism. However, Capitalism has its own mythologies and notoriously inaccurate accounting systems.